Robert Hartzler (1919-1994) Photo from Eighth St. Mennonite Church website

Robert Hartzler (1919-1994) Photo from Eighth St. Mennonite Church website

What a Preacher’s Sermons Tell Us: A Profile of Robert W. Bob

Hartzler (1919—1994)

I first met Robert W. Hartzler in 1984 when I was a candidate for pastor at Eighth Street Mennonite Church in Goshen, Indiana. Bob, as he was fondly known, was a member of the search committee, which was a rather unusual position for a former pastor of the congregation, and particularly for Bob who was very clear about his role in the congregation as a former pastor. Over the seven years that I pastored the congregation, from 1984 to 1991, Bob kept a low profile, was always supportive. I learned to respect this man who clearly had had a great influence not only in the congregation at Eighth Street, but was also instrumental in establishing other institutions that continue to make their mark in northern Indiana and beyond.

Bob Hartzler was born near Middlebury, Indiana, to Floyd and Mary (Leek) Hartzler, who had been members of Silver Street Mennonite Church, east of Goshen, but affiliated with Eighth Street Mennonite when the family moved into the town of Goshen. Both churches were part of the Central Conference of Mennonites, a group rooted in the nineteenth-century ministry of Illinois Bishop Joseph Stuckey, and in 1946, after years of cooperation with the General Conference Mennonite Church, formally joined the GCMC.1

Bob graduated from Goshen High School in 1937 and from Goshen College in 1941. His father died at a young age. Bob supported himself through school by working as a linotypist for the Goshen newspaper. In 1942 he married Emma Blosser of Wayne County, Ohio.2 They eventually had three sons: Gregory A., Geoffrey O. (1946-2012), and Kim N. (1952-1969).

During 1940-1942, Bob served as a student pastor for Zion Mennonite Church, a Central Conference congregation in Kouts, Indiana, seventy-five miles west and south of Goshen.3 He drove there every other weekend. Bob served as pastor at Silver Street Mennonite from 1942 until 1945, and then became assistant pastor at Eighth Street, serving alongside noted General Conference leader A. E. Kreider. When Kreider departed Goshen in 1946 to assume an assignment with Mennonite Central Committee, Hartzler became the sole pastor at Eighth Street, whose membership then stood at about 275. He continued in that role until 1962. During his early years of ministry, Bob enrolled in the new seminary program being offered jointly in Chicago by Mennonite Biblical Seminary (GC Mennonite) and Bethany Biblical Seminary (Church of the Brethren). He completed a B.D. degree in 1949.4

Alongside his ministry at Eighth Street, Bob Hartzler was deeply involved in organizing and launching many institutions and programs that served the conference and the community.5 He was a member of various Central Conference committees. During the late 1940s he was instrumental in launching a conference camping program, and in locating property and constructing what became Camp Friedenswald near Cassopolis, Michigan, in 1950. He was the driving force behind the establishment of Oaklawn, a Mennonite-affiliated mental health center in Elkhart County, and served as Oaklawn’s first executive director from 1962 to 1978. He was also at the center of planning for Greencroft, a Mennonite-sponsored retirement community in Goshen, and served as Greencroft’s first executive director from 1966 to 1981. The time demanded by these involvements led Bob to resign as Eighth Street’s pastor in 1962 and focus on Oaklawn and, later , Greencroft. Even in retirement, he continued to be active in new initiatives, such as helping during the mid-1980s with the development of Menno-Hof, a Mennonite-Amish information center in nearby Shipshewana. Along the way Bob spoke at conference sessions, was a guest lecturer at places such as Freeman Junior College in South Dakota and Mennonite Biblical Seminary, and presented papers to study commissions, particularly in the area of stewardship.

Knowing of Bob’s extensive work in and for the church, locally and more broadly, I was shocked one day as I walked past his house on my way home and Bob called me into his garage. He pointed to a wheeled garbage can sitting there and told me it contained all of his sermons. He said he did not want his kids to have them (without any explanation) and that he didn’t want them to go to the archives. He said he would give them to me, but if I didn’t take them he was going to pull the garbage can to the alley and let the garbage man take them.

While I wasn’t sure what I would do with them, I was not about to let them disappear into the landfill. And I do like church history, which I was sure was reflected in Bob’s sermons. So I wheeled the garbage can home and transferred the file folders into file boxes. Thereafter they accompanied me on my moves to Nebraska, South Dakota, and finally to Calgary, Alberta, assuming all along that someday I would do something with them and eventually deposit them in an archives, despite Bob’s wishes.

Since 2013 was Eighth Street Mennonite Church’s centennial year, I decided that this was incentive enough to begin to learn more of who Bob was from his writings and sermons. All the manuscripts were in labeled file folders, which helped, but my first task was to inventory the documents. Sermons are the bulk of the material, beginning in 1941 and continuing through 1962. In all there are 881 sermons, many of them preached on more than one occasion.

There are meditations for 46 funerals, including items from three memorial services between 1945-1946 for young men from Eighth Street killed in World War II – Harold E. Oesch, Ed Whirledge, and Russell J. Bechtel.6

Several folders contain prayers, generally full-page, typed prayers. It is clear Bob took the pastoral prayer very seriously and a study of those prayers could prove valuable in itself. There is a folder of seminary papers from the mid-1940s when he attended Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Chicago, as well as a reflection given at the 10 year anniversary of the seminary. There are numerous addresses given at commencement and baccalaureate services, as well as many articles and addresses given at Central Conference or General Conference meetings.

Scattered in many of the folders are bulletins from the services at which the sermons were preached. These, too, give interesting glimpses into the life of the church, particularly during the war years. For example, an announcement during the war noted the need for some gas coupons to enable persons to attend a meeting some distance away. And one note in a 1947 bulletin thanks the congregation for a new car delivered to the “parsonage family.”

An address entitled, “Why A Greencroft?” was given at the dedication ceremony for Greencroft. Several items pertain to Oaklawn, and several to Camp Friedenswald , including notes for the dedication of the David Smucker Memorial Fountain.7 Poems, hymn stories, and some scripts for illustrated art lectures are also included.

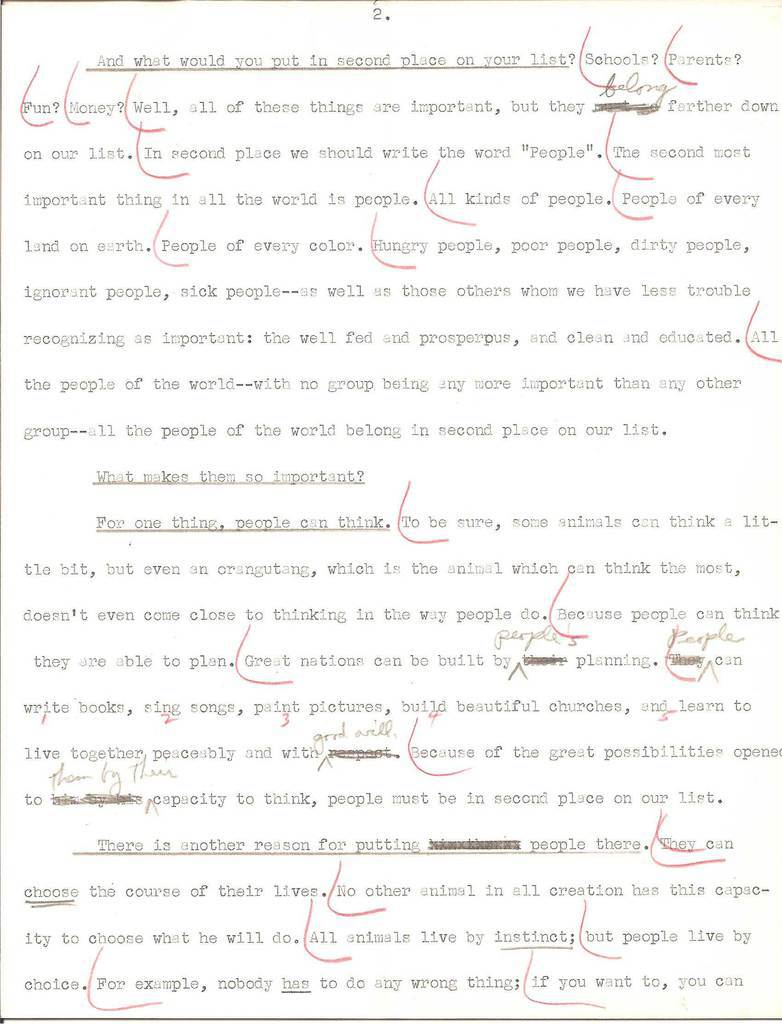

A red half-circle marking on most of his sermons seems to be some kind of delivery reminder, although its purpose is unclear.

A red half-circle marking on most of his sermons seems to be some kind of delivery reminder, although its purpose is unclear.Early material is handwritten, either as outlines and notes or as full manuscripts, while later material is all typewritten. Some sermons are in both outline as well as manuscript form, and many of them have edits, deletions, and other marks on them –some clearly revised for different occasions. A red half-circle marking on most of his sermons seems to be some kind of delivery reminder, although its purpose is unclear.

Some of his marginal notes were interesting, particularly to someone who also preaches. I especially liked a note he had written on a Thanksgiving sermon from 1959: “This whole re-hash was used at Eighth St. 11-23-58 – Never use any part of it there again.”

Reading Bob’s sermons, it is striking how many quotations and poems he included, and how much research he cited. He was obviously well read. In fact, at one point he said, “Perhaps some of you have turned from contemporary novels in disgust, but if so, you have shut yourself off from the quickest & easiest way to keeping informed on the mood and temper of our day. And that’s one thing a preacher can’t afford to do.” He often quoted poems, some with no author given – which makes me wonder if they may have been written by Emma, his wife, who was an accomplished poet.8

While humor was not a major factor in Bob’s sermons, it was not unknown. Perhaps my favorite example was found in a sermon of his entitled “Christian Morale” preached on February 24, 1957. It was part of a series of sermons that Bob preached about each book of the Bible. He began his sermon on Philippians with this story:

“As some of you know, my wife is confined to her bed as a permanent invalid. A year or so ago I met a man up on Lincoln Avenue who, as many do, inquired about her progress and after having done so made the further observation, ‘I have heard that her morals are good!’ Of course, I agreed with him, for I have never had reason to doubt her morals. But I think that he meant to comment upon her morale, which is also good.”

The story is significant both in the humor that it shows, but perhaps more in the fact that this is the only time I found any reference to Emma in Bob’s sermons. In 1952 Emma was stricken with polio and spent the rest of her life confined to an iron lung or a rocking bed. The fact that this is the only mention of her, even when she became sick, is rather startling. Emma died in 1991.9

Nor do I recall him referring to his three sons, other than a mention of Geoff’s birth in 1946. In a Thanksgiving sermon that year he commented: “While I make preparation to give profoundest thanks for the little son by whom our home has been blessed and who has every material thing that he needs, I am disturbed by reports of newborn European children being wrapped in newspapers.”

I don’t think he was referring specifically to his own children when he talked about Paul’s letter to the Corinthians and said that sometimes Paul was severe because he loved the church, just like we love our children: “Because we love the little monsters, we must discipline them” (The Soul of a Saint, Jan. 27, 1957).

He did tell a few jokes, primarily in speeches other than sermons, but it was sometimes his comments within sermons that I found most amusing. For example in a sermon on Solomon he noted that Solomon had “700 wives, 300 concubines!” then penciled in the comment, “Imagine 1000 pairs of nylons.” At another time he preached a sermon on Samson and Delilah and noted that Delilah got a good price for her betrayal of Samson, 1100 pieces of silver, or about $25,000. Then he added, “One might be surprised how many women would leave their husbands for $25,000” (“A Strong Man and a Woman”). And in a sermon on dealing with conflict he noted that the first step in dealing with conflict was to release the tension, but said, “Now here I do not mean swearing at the one you hate, although that will often relieve your tension, it`s a stupid thing to do” (Dealing with our Hatreds, July 5, 1959).

In several sermons he quoted an unattributed source in describing humans as “10 gallons of water, 24 pounds of coal, 7 pounds of lime, one and 4/5 pounds of phosphorous, a half teaspoon of sugar, with nine times as much salt, some oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen, iron enough for one large nail, and a few other chemicals.” He also noted a philosopher who once said, “the more he sees of men, the better he likes dogs” (What Is Man? Oct. 23, 1955).

Something one readily notices in Bob’s sermons is the clear stand he took on many of the social issues of the day. Numerous times he talked about the fact that some people want preachers to stick to strictly “spiritual things” but that God has a concern for all of life, and therefore a preacher must speak on many things. In fact he said he heard a man once speaking about his minister and saying, “He never says anything about war and peace, but he certainly does preach the gospel.” That, said Bob, is “just not possible….”

Bob was also clear that the church had something to say to society. In a sermon entitled “The Problem of Ethics” (1958) he noted, “Among the leaders of the church in America today there is a growing agreement that we can no longer think of the religion of Jesus as merely a personal religion, having relevance only for individuals, as we have supposed in the past. Instead, these men are saying, Christianity is a social religion and that its deepest meanings are for society rather than for individuals…They are saying that the ultimate significance of Christian ethics lies in politics, the chief instrument of which has been warfare.”

After reading about three-quarters of the sermons as well as many of his other manuscripts, I came to see a preacher in tune with the issues of his day, fully grounded in Mennonite theology, and active in his community. He was not afraid to address controversial issues or to call his congregation to greater faithfulness, which I’m sure not everyone appreciated. While it is hard to summarize all the material, following are some of the themes that appear repeatedly and give a glimpse of the man and his times.

During the war years, Bob’s sermons spoke about the horrible things that were happening in Europe and the Pacific. He was clearly a pacifist in his understanding of the Gospel and wasn’t afraid to speak out about it. This is most interesting since Eighth Street Mennonite had an equal number of men who joined the military as claimed conscientious objectors status during World War II. After the war ended, memorial funds given in honor of six men killed in the war was used to purchase a new pulpit and a small plaque named these fallen, which may have been more casualties than any congregation in Goshen of any denomination suffered.10

In his early days of pastoring, he struggled at times to find appropriate things to say in the face of war. In a sermon outline, evidently from the Sunday following D-Day (1944), he noted how he searched in vain for a clear Scripture for that Sunday, but could find none. He finally settled on Romans 11:33 and declared a clear faith in the sovereignty of God, the only thing one can cling to in such times.

In another speech entitled “The Builders” and addressed to a youth convention, he gave a resounding call to the youth to be builders for peace – both a personal peace and a societal peace. He stated that this is what they were born for as Mennonite youth and therefore they should follow that calling. He criticized King Edward VIII for abdicating his throne in 1936 “so that he might have Wally” [Wallace Simpson]. Hartzler stated, “For he was the one who was born to serve his people as a ruler and a king and was admirably qualified by his God-given talents and abilities for that very position….He was false to the cause to which he was born.” In the same way he argued, Mennonites have an innate obligation to work toward a peaceful world.

He was also clear that being a pacifist was more than just a belief. In a sermon entitled “Frontiers of the Spirit” (Aug. 3, 1941, Kouts, Ind.) he noted many physical frontiers that are gone, but contended there are still frontiers to conquer, citing “a. cyclotrons b. uranium c. solving the age old problems better than they have been solved in the past.” He then went on to cite several modern spiritual frontiers, the first one being Jesus’s words to love your enemies and do good to them that hate you. Good old Mennonite doctrine he said, “but it is fruitless if we adhere to it simply because it is Mennonite doctrine – if secretly in our hearts we are cheering every British victory and cursing every German advance.”

It is during the Korean conflict (1950-1953), however, that he spoke out most clearly against war. In a sermon entitled “Korea and the Gospel” (July 20, 1950, Eighth Street) he said, “The fighting in Korea is not the will of God. The ends may be wonderful, but the means are wicked.” And “Christianity is about methods. Everyone wants the same ends, but the way of Jesus is a method and how we achieve those ends. If you give up the means, you have abandoned Christianity. Going to Korea is such an abandonment.” He was even blunter in another sermon when he stated, “When a man accepts military service, or a Christian supports war, he admits defeat as a Christian…. He is acknowledging before men that he is not committed to Christ really, but to the secular God of violence” (The Dagger or the Cross, Eighth Street, Oak Grove, January 1952)

While Bob spoke well of the United States and the freedoms enjoyed there, he laid as much blame for war on the U.S. as the Russians, and spoke against the kind of nationalism that puts country above all else. In a sermon entitled “The Christian and the State” (January 31, 1954) he said, “Some people are quick to assume that Paul’s teaching, ‘Let every person be subject…’ is a green light for loyalty tests and nationalistic, noisy patriotism. It is not so.” Bob agreed that we submit to government because we know order is necessary, but the Christian, he went on, “doesn’t become emotional, about government or his flag, nor does he engage in patriotic harangues” because “Christianity transcends national lines.” In fact, he said, “The American Christian has stronger and more important ties with the Russian Christian than he has with non-Christian Americans. A Tolstoy is much more nearly our brother than is a Senator McCarthy.”

Hartzler even made a suggestion that certainly would have been out of step with most people at the time when he said, “Christians would be far less respectable, but they would be far more Christian, if they insisted we deal with the Russians along lines suggested by the Gospel, rather than along military lines” (Perils of the Christian Life, May 4, 1958; II Peter).

While some have questioned how strongly the General Conference Mennonite Church upheld the doctrine of non-resistance during the Second World War and the early cold war, it is clear that, at least at Eighth Street, people heard a clear message against nationalism and war.11

Although the civil rights movement was just heating up in the early 1950s, time and again Bob spoke out against segregation.12 While he sometimes cited the progress that had been made, more often he spoke against the continued policies of segregation, even speaking rather forcefully about the segregation that was practiced in Goshen itself. In a sermon entitled “The Grace of Humility” (Nov. 8, 1953), he cited two examples of people who don’t understand the Christian faith, one of which is a person who is a “longstanding member of church but says he hates Negros.” In another sermon on “The Narrow Way” (July 15, 1956) he said, “Suppose you are a resident of a community which practices racial segregation, as all of you are.”

Yet it was possible at the same time for Bob to carry some of the prevalent attitudes of the day, as when he talked about the “native of Africa living in the depths of the dark continent” (Is Man Free? 10-30-55) or a sermon in 1949 in which he said, “In the Congo black skinned natives are observing communion who are superstitious and ignorant and who are still far from the abundant life.”

Bob was optimistic about the direction the world was heading. Bob clearly saw the United Nations as a sign of God’s activity in the world for good and he often spoke approvingly of the UN. He saw the UN as “an attempt, even if an imperfect one, to establish some Christian concepts of ethics and morality on a world scale” (Getting Ready for Tomorrow – Nehemiah) and hoped for a time when nations would work together for peace in the world.

And he saw Anabaptist principles as having a role in making the world better: “The principles on which and for which our church and others like it stand today constitute the hope of the world. They constitute the only true strength a people can have. I am convinced that in the decades ahead we shall see a movement in the direction of those beliefs, for in that direction lies progress” (The Christian’s Mark, Silver Street, July 19, 1942).

Unfortunately, some of his optimism has perhaps not played out as he expected. In a sermon on the commandment to not steal he said this needed to apply to all levels of society, and stated, “Our laws are continually being modified to make it less easy for the rich and powerful to plunder the world’s supply of wealth” (Not Steal, 1955). One wonders what he would say about that subject today, given the growing income and wealth gaps.

As with his support for the UN, Bob promoted the activities of the Christian ecumenical movement. He often spoke in churches of other denominations, as well as at community gatherings. In a series of short talks given at a Mennonite Biblical Seminary Alumni Banquet in 1957 he took his fellow Goshen pastors, particularly the Methodists and Presbyterians, to task for their refusal to participate in ecumenical events, noting they are only interested in pulling Mennonites into their own churches.

He was also an early promoter, it seems, of Mennonite cooperation. In a sermon promoting cooperation of all kinds, he asked: “What shall we say? Can we be serious about this? Can we expect that the day will ever dawn when the so-called Old Mennonite Church and the General Conference Mennonite Church will get together?” He said he couldn’t answer that, but there didn’t seem to be apparent obstacles to it happening (We Do Not Stand Alone, May 29, 1960).

Bob was concerned about a growing materialism in society and the church. He preached a series of sermons on the Seven Deadly Sins, and in speaking of gluttony he quoted philosopher Robert Maynard Hutchins who wrote, “that we have found a new way of getting rich by buying things from one another that we do not want, at prices we cannot pay, on terms which we cannot meet because of advertising we do not believe” (The Sin of Gluttony, 2-22-59). And he blamed at least part of the problem on capitalism. In a sermon in 1954 he noted, “Henry Ford & George Baer once said, ‘The right and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for, not by labor agitations, but by the Christian men to whom God in his infinite wisdom has given control of the property interests in this country.’ The fact that fully half of the American people still believe that [contention] today reveals the monstrous injustice, the failure of distribution, and the denial of brotherhood which is inherent in capitalism” (The Cloud and the Fire, Nov. 21, 1954).

But he was not against everything material. In 1958 he preached a sermon entitled “Some Duties to Self” in which he said, “And one might add the further observation that every person owes it to himself to acquire enough of this world’s material goods to make possible the values to which I have been referring. After all, one cannot operate a family without a certain amount of equipment – it takes a home and a television set at least!”

One of Bob’s clear interests was in the area of health, and particularly mental health. There is a thick folder of sermons related to these issues, and he noted that each summer he preached a series of sermons on health. There is one sermon entitled “Religion and Health” that he preached twelve times, in different locations, between 1961 and 1966, mostly while administrator at Oaklawn. Whether Emma’s illness made this topic important to him is hard to say, but one could speculate that this certainly had an effect. He was clearly well read on the subject, citing studies and authors to make his points.13

As he was leaving Eighth Street in 1962 to take on the role of administrator at Oaklawn, he noted that some people lamented the fact that he was “leaving the ministry.” However, he explained very clearly that to him the new role was an extension of his ministry. In numerous sermons he cited the importance of faith for good mental and physical health. He did not discount miraculous healing, but he saw a clear role for the medical profession and noted how God is always the healer, no matter how it happens.

Bob spoke and wrote on several occasions about the major building expansion project that Eighth Street undertook during 1956-57, adding a large education wing, fellowship hall, and office space. In some notes and an article for the October 1961 issue of Mennonite Life, he noted that with the new building the membership had grown and the giving almost doubled.14 However, he did have some words of advice for those contemplating a building project: get professional help, get a church architect, and above all, don’t have a building committee! It would be interesting to know the story behind that comment.

He was very clear, however, that the building was only a tool and it is what we do with the new building that makes the difference. In an address given to the Goshen City Church of the Brethren (March 31, 1958), he noted that the building is the means to evangelize, worship and give Christian education to those who come.

He made the same comment regarding the development of Camp Friedenswald. In a sermon in 1951 he said, “We are building a camp at Shavehead Lake. It is of no account if it will not work for the same purposes for which God works” (What is God Doing, June 3, 1951).

I believe that Bob Hartzler’s view of the Bible would have been considered progressive for the 1950s, and might be considered so by some even today. In his preaching he was free to suggest that certain passages were not to be taken literally, including the creation accounts, the fall, and the flood. He stated, “I must say what I have said earlier about the story of creation and about the story of the fall of man, that this is by no means literal history, and that we miss the point if we insist upon thinking of it in such terms” (The Time of Recompense, Sept. 18, 1960).

In discussing the Exodus, Hartzler noted, “Because long after it happened it became the faith of certain Jewish historians that it was the Lord’s doing that delivered Israel out of the hands of the Egyptians, the complexion of the world has changed” (The Lord Saved Israel, Sept.16,1956) and he even had a comment about Paul, saying, “Sometimes the judgments which St. Paul offers do not commend themselves to us and we are forced to think they do not square with the Gospel of Christ.” But, he acknowledged, they are usually good (The Wise May Bring their Learning).

It took him 105 weeks, with time out for special occasions, vacation, and so on, to preach a series of sermons, one sermon on each book of the Bible. Clearly some of them were less than favorites. He began his sermon on Esther by saying, “I would like to skip this book.” And he noted that the book of Nahum ought to be appreciated for its great literary excellence, because Nahum was not the keenest prophet, as he had only one idea – “And that idea is not the most edifying one to be found in the Bible.”

Bob also had a word for those who used the Bible as a sort of talisman or good luck charm. On Universal Bible Sunday, December 8, 1946 he said, “There is a lot of pious nonsense which goes on in connection with the Bible.” And continued “If you are a soldier you are no safer from a sniper’s bullet if you have a Bible in your breast pocket than if you had a bag of peanuts or any other book there.”

But his theology clearly saw the way of salvation through Jesus, and God as active in the world. Many sermons ended with a call to discipleship and an acknowledgement of God as the source of our hope. He clearly saw the church as a force for good in the world, and called people to faith. He was a strong proponent of Christian education at all levels and dutifully preached a sermon each year for Christian Education Sunday.

Yet he wasn’t hung up on many finer points of theology. He did spend some time preaching about the “end times,” although not because he particularly wanted to. “I preach this material this morning in partial fulfillment of my sacred duty to teach the congregation,” he began. “I preach it to satisfy the curiosity of some. And I preach it because I fear there are also those among us who are becoming ensnared in false doctrines which may be tickling to the ears but which are untrue to the Word of God,” a reference to premillenialism (The Second Coming of Christ, 1945) He didn’t have much good to say about premillenialism nor about scaring people into heaven, noting that “The picture we have of a lake of fire, of demons with pitch forks and pointed tails tending it, and with people writhing endlessly in anguish, surely must be placed completely outside the circle of Christian thought” (The Last Judgment, Jan.29, 1956).

I still have no idea why Bob chose me as a recipient of his sermons and manuscripts. Perhaps I happened along at the right time, although I suspect he was watching for me to walk by, since I generally passed that way each day. Bob only lived three years after I left Goshen, so I never had a chance to talk with him about the material. Despite Bob’s wishes, all of the material has now been placed in the archives at Bluffton University where it can be available to others as well. But whatever Bob’s motives, I am glad I hauled that garbage can home, for the material it contained provides a glimpse into the church and at least one man’s thinking during a span of time that saw tremendous changes in the church and world. Yet many of his views and sermons could just as easily be preached today, and I felt privileged to get that glimpse.

After reading Bob’s sermons I had to wonder, “What I should do with the boxes of sermons I have preached over the past 37 years? Would anyone find them interesting? And what would they say about me or about the church and world I have lived in?” Maybe when I retire I’ll have to keep my eyes open for some young pastor who walks by my house.

The History of the Eighth Street Mennonite Church, 1913-1978,unpublished manuscript, 1978, pp. 137 and 150. Pages 150-260 of this manuscript detail the history of the congregation during Hartzler’s pastorate.

Lusty Swallows of Life,The Mennonite, Feb. 11, 1992, 51-52, details Emma’s remarkable life. In 1992 Robert married Josephine Huser Troyer (1926-2013).

The History of the Eighth Street Mennonite Church,116-29, 141-43.

Portrait of aMennonite World Review, January 10, 2014, 1, 12-13, provides detail on race relations in Goshen during this time, and mentions Eighth Street’s relatively progressive stance at the time compared with other Mennonite churches in the area.Sundown Town,

Building a New Church,Mennonite Life, 17 (October 1962): 150-51.