The Fehrs: Four Centuries of Mennonite Migration

The Fehrs: Four Centuries of Mennonite Migration

Review: The Fehrs: Four Centuries of Mennonite Migration

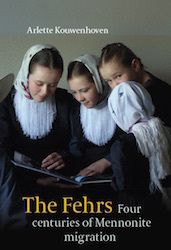

Review of Arlette Kouwenhoven, The Fehrs: Four Centuries of Mennonite Migration (2013). Published by Winco Publishing, Leiden, the Netherlands, 2013. First published as De Fehrs, Kroniek van een Nederlandse mennonietenfamilie, Uitgeverij Atlas, Amsterdamk, Antwerp 2011

It is not until the end of the book, that we learn what first piqued author Arlette Kouwenhoven’s interest that led to the publication of The Fehrs: Four centuries of Mennonite migration: a chance meeting in southern Texas and a reference pointing to Old Colony Mennonites of Chihuhua, Mexico. Dutch migrants, devout people, pioneers – all long-held passions of mine,

she writes in the afterword.

Kouwenhoven is a Dutch cultural anthropologist, and her surname does appear, in some variation, in Anabaptist archives in the Netherlands. But she is not Mennonite, and such a distinction is immediately conspicuous to me, as a Mennonite who has only read Mennonite books written by Mennonite writers.

The line between Mennonite and non-Mennonite seems particularly strong in focusing on the story of Old Colony Mennonites, now living in Mexico after four hundred years of restless moving and whose recent incidents of drug running have made them almost a spectacle. Will Kouwenhoven treat them respectfully? Will she understand that fine line between petty and substantive; will she comprehend the subtle nuance between self-righteous and pure? Will she get

the fundamental Mennonite story?

The Fehrs

is a treasure hunt, a journey documenting the people bearing the name Fehr, or DeFehr or de Feer over a four-hundred year span. It begins with Anabaptists in Amsterdam in 1612, follows the trail to Poland and Prussia (1612—1789), then to Russia (1789–1874), on to Canada (1874–1922) and finally to Mexico (1922—2011). It begins with Gijsbert de Veer, born in 1556, with the latest member of the family, Jacob Fehr, born in 2010.

The detail and continuity of the documented male lineage is extraordinary, even for Mennonites with their long communal histories and interwoven family stories. Yet by staying true to the Fehr family tree, it becomes more of a man’s story, with little or no opportunity to feature the adventures, experiences, accomplishments and views of women,

Kouwenhoven acknowledges.

Having said that, the completion

of the story is one of the book’s strengths, because this one family’s story encompasses themes interwoven through Mennonite history. Here are the devout believers, pursuing a radical interpretation of Christian discipleship, resulting in a separation from the outside world. Here too are the constant schisms of Mennonite life, groups separating over lifestyle choices or religious practices.

Like other Mennonites, the Fehrs move around the globe, seeking religious freedom and economic opportunities. To get from Amsterdam to Sabinal, Mexico, Kouwenhoven’s Fehrs choose the purest

path, repeatedly eschewing any accommodation to a dominant culture. Like the Fehrs, my ancestors were Plautdiestch

speakers with roots in the Netherlands, organizing first in Prussia, then moving to the Russian Ukraine and finally to central Kansas in 1874, the same year the Fehrs move to Manitoba. But that was the last geographic move of my Mennonite group. I grew up with a strong sense of Mennonite community that refused to conform to the standards of the world, but in a kind of moderate and practical way. My parents, who both learned Low German as their first language, made no attempt to teach that dialect to my siblings or myself. We were Mennonites first, but in a decidedly American context.

But does that make the Fehrs more pure

than myself? Kouwenhoven recounts a conversation between two Mennonite men, separated by the decision to move to Mexico. One stayed behind in Canada; the other moved to the Mennonite colonies so his children could learn in their own religious schools and not be forced into public education, among other restrictive practices. The one who stayed in Canada, admitted his children had become English

by not moving on. But that had been a good choice, because the Mennonites who had moved to Mexico became more Spanish now than ours are English.

In her introduction, Kouwenhoven writes of her own affinity for the people she traced through four hundred years. Some casual probing strikes a chord somewhere, an unexpected sense of belonging, a nostalgic feeling is awakened that is not based on any apparent shared experience, and yet is so appealing that the idea cannot be abandoned.

For all the severity of the most insulated Mennonite cultures, there is also something appealing in the safe, enclosed world, marked by a sense of belonging and caring for one another.

Such a place of deepness should not be dismissed easily. Kouwenhoven’s skillful analysis and description help make that possible.