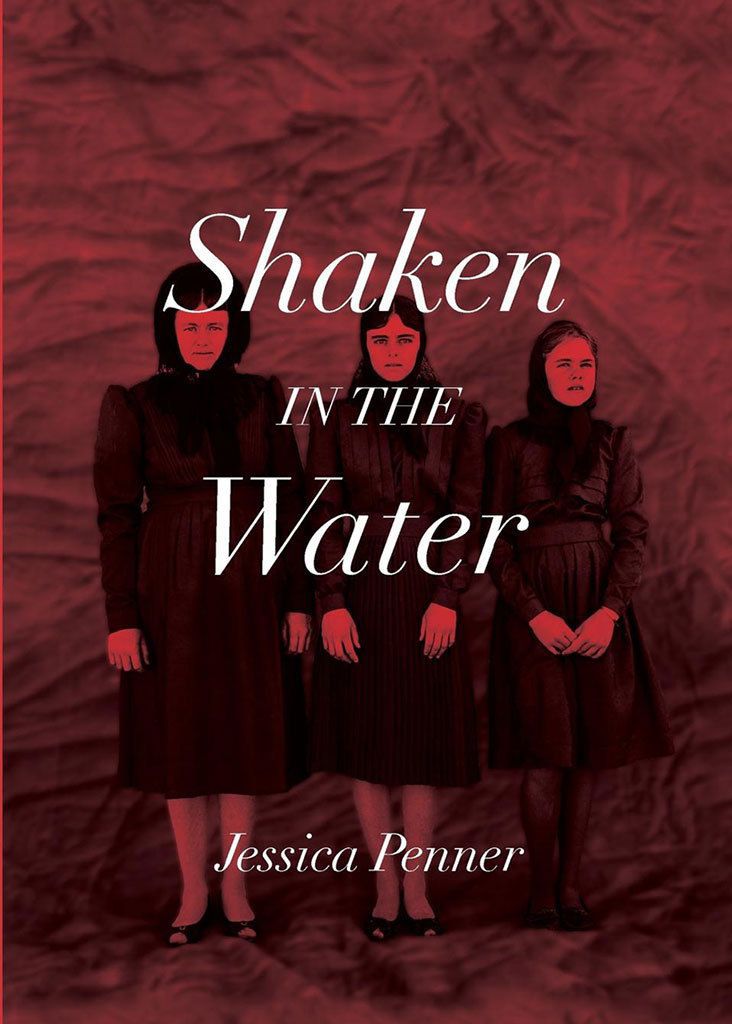

Shaken in the Water

Shaken in the WaterJessica Penner

Foxhead Books

Review: Shaken in the Water

Penner, Jessica. Shaken in the Water. Foxhead Books, 2013.

Shaken in the Water is Jessica Penner’s debut novel. It is a novel about it what it means to transgress boundaries of an inscribed cultural and religious heritage; it is a mythology of origins and an exploration of story-telling; ultimately, it is a fictionalized memoir about what it means to be a woman, and Mennonite. As a woman who was neither raised in Kansas, the setting for Penner’s story, nor as a Mennonite, I found Shaken in the Water an illuminating read. As her title suggests, Penner’s interest in the place of faith and what she callsgreatnessin the lives of the multiple generations that populate her novel is both jarring and cleansing. And it jives with my own experience of attempting to integrate into Mennonite culture in the Mid-west.

Shaken in the Water follows the story of Agnes, born a marked

woman in 1903 Kansas. Moving backwards and forwards through the generations of Agnes’s family, the familiar tale of both men and women plagued by the trials of life in a small town are revealed. The characters struggle with the recognizable realities of love, loss, poverty, friendship, betrayal, growing-up and dying. However, in addition to the familiar, Penner fills her novel with the pain of being not-Mennonite

, of language barriers, of the stillness

verses action

philosophy of pacifism, of Home and Place, of Shunning, and of Voice/Voice-less-ness are woven with a deft touch into the magical realism that Penner deploys as her narrative device. Unbound Hair, Tiger Birthmarks, the Voice of the Wind, Jungles and Gardens are as much characters in her narrative as are the women of Agnes’s family, around which the story whirls.

In this way, Penner’s mythology of Mennonites reads much like the Native mythologies of Leslie Marmon Silko, or of Gloria Anzaldua; she weaves the metaphors of Mennonite culture and faith into the realities of family and the contradictions of the betrayal and redemption that are life in any and all cultures. The result is a novel that, while certainly not an easy beach-read, is hopeful. And, I think, helpful for those of us who struggle to understand the complexity of what it means to be a person of faith.