Daughters in the City: Mennonite Maids in Vancouver

Daughters in the City: Mennonite Maids in Vancouver

Review: Daughters in the City: Mennonite Maids in Vancouver

Daughters in the City: Mennonite Maids in Vancouver, 1931-61. Ruth Derksen Siemens. Fernwood Press, Vancouver B.C. 2013. 93 pages.

Daughters in the City is a coffee table book detailing the experiences and history of post-WWI and WWII Mennonite refugee girls who worked as maids in Vancouver to help pay off their family’s travel debts. It uses narrative and photographs to bring to life the activities of the two Mädchenheime (girls’ homes) in Vancouver that served the needs of the Mennonite maids and the experiences of the young women who worked as maids. Set in amongst the narrative, are several page-length insets that focus on a particular woman’s experience, whether matron or maid. Daughters in the City contributes in a valuable way to the small but growing body of research on Mennonite Mädchenheime in Canada and can certainly serve as a springboard for further research of this chapter in Mennonite history.

Siemens begins her account with a brief history of Mennonites in Russia and what precipitated their flight to Canada and then launches into the history of the two Mädchenheime in Vancouver and the experiences of the young women who, through their working lives as maids, intersected with them. She treats important themes like the working conditions of the maids, the church politics in establishing and closing the homes, the invaluable contribution by the matrons of the homes, and the vital role the homes played for the young Mennonite women in providing social opportunities, employment services and moral supervision.

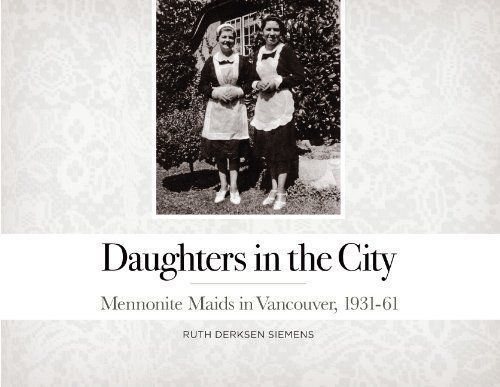

The primary research that went into this book is truly remarkable. Siemens lists thirty-one women who were interviewed and whose experiences fill the pages of this book. But Siemens also uses church records, immigration records and church periodicals to establish an informed picture of the broader context of the maids’ experiences. The collection of photographs displayed on the pages of the book entails an impressive number and provides a rich text with which to understand the experiences of the maids and the history of Vancouver’s Mennonite Mädchenheime. From candid shots of a young women stretched out on a couch exhausted after a day of work and Sarah Wiens having a playful moment

in an empty refrigerator crate (p. 40), to the formal shots of maids posing in uniform in front of their employer’s home and the group photos of the young women lined up in front of the Mädchenheime, the photographs add so dynamically to the breadth of the experience Siemens describes in her narrative. It is therefore deeply disappointing that the quality of their reproduction is so poor. The number of errors, grammatical, organizational and otherwise–enough that a sheet of errata needed to be included–also distract from what should have been an exceptional book.

The hand of a scholar is evident throughout the book in the solid research that is reflected in the text and yet this is not an academic book. And that is as it should be. Though the author does not describe it as such, this book is, I think, a tribute to the many women who played an invaluable part in the sustenance of the Mennonite refugee community in British Columbia in the early to mid-twentieth century. What their contribution was to the economic, religious and cultural vitality of British Columbia’s Mennonite community is made very evident on the pages of Daughters in the City.