Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets a Glittering World

Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets a Glittering World

Review: Bonnet Strings: An Amish Woman’s Ties to Two Worlds and others

Furlong, Saloma Miller. Bonnet Strings: An Amish Woman’s Ties to Two Worlds. Scotdale: Herald Press, 2014.

Janzen, Jean. Entering the Wild: Essays on Faith and Writing. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2012.

Kreider, Robert. Coming Home: An Autobiography of My 1952—2011 Years.

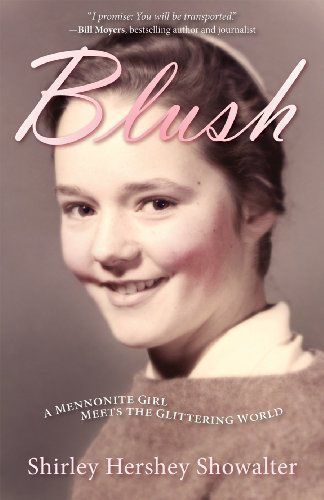

Showalter, Shirley Hershey. Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets the Glittering World. Scotdale, PA: Herald Press, 2013.

In the life-writing course I teach each year, students often struggle to understand the distinction between memoir and autobiography. The words are sometimes used interchangeably, after all, and even bookstores (or, at least, the brick and mortar ones still standing) place autobiographies and memoirs side-by-side on their shelves. One mega book-selling chain mixes biographies, memoirs, and autobiographies and puts them in a section titled Biography.

No wonder some folks are confused.

Although both autobiography and memoir are written in first person, and ostensibly by the narrator him or herself, other distinctions separate these two genres. Autobiography often covers the span of a writer’s life, highlighting important details of that life up to the point of the book’s writing. Memoir, on the other hand, focuses on one aspect of a life; it is often organized around a theme or idea; it does not endeavor to be comprehensive, and sometimes, the details left out may be as significant as those the writer chooses to include. Although there are exceptions, too, I would argue that autobiographies are often written by those whose public life will be especially interesting to a reading public: presidents and dignitaries, business leaders and Hollywood stars, famous athletes, and the likes of teen pop star Justin Beiber (whose autobiography, written when he was still a teenager and out of legal trouble, must surely be a slim volume).

In the history of Mennonite letters, the first-person narratives written and published have primarily been autobiographies, book-length stories of Mennonite leaders, academics, missionaries, and others who have dedicated their public lives to church service, and whose work readers might consider exemplary. Yet while Mennonite autobiographies are still being written and published, in recent years, more and more Mennonite authors are turning to the memoir, suggesting a shift—however small, potentially imperceptible—in how Mennonite women and men figure their life stories.

The increasing popularity of the memoir, both in wider and in Mennonite culture, also challenges notions about whose narratives we privilege, for the memoir—unlike the autobiography—makes wider berth for ordinary people to tell their stories, rather than relying only on those with rich public lives to recount their experiences. Of course, some public figures choose the memoir as the best way to narrate their life stories, too; but the memoir also makes space for others whose lives might hold interest for readers: because they are unique or even because, in some ways, the writers’ lives are just like ours.

Although autobiographies about Mennonite leaders continue to find an audience—as, for example, Robert Kreider’s Coming Home, published in late 2012—several memoirs produced in the last two years exemplify the notion that ordinary people might also have important stories to tell. These new memoirs are written by women whose lives have not been lived in public spheres; they are not Mennonite leaders, nor are their books necessarily focused on their working roles. Instead, they tell stories of quiet but astounding experiences: of an Amish woman, Saloma Miller Furlong, who decides to leave her tribe; of a Mennonite poet, Jean Janzen, whose understanding of the world is shaped by her art. Another memoir published in 2013 was written by a Mennonite leader, Shirley Showalter. Yet instead of narrating her ascendency to leadership and her time as president of Goshen College, Showalter’s memoir focuses on her youth, and on the conflict she felt, between being in the world but not of it.

Showalter’s excellent book, Blush: A Mennonite Girl Meets a Glittering World, stands out as some of the best work done by Mennonite memoirists and, I think, will mark a shift in Mennonite letters. For while she might well have detailed her public life from its germination to its conclusion, Showalter made different choices, and wrote a far different book: one that has enjoyed broad popular and critical acclaim, having gone through three printings in the five months since its release in September 2013 and having been honored as one of the 50 best spiritual memoirs of the year by the Spirituality and Practice website.

Showalter begins her own narrative with her parents, Barbara Hess and Richard Hershey. Rather than miring Blush in long genealogical lists, as many Mennonite autobiographies in the past have done, Showalter creates rich characters in her parents, allowing us to see—through narrative—who they were, what their dreams entailed, the times when they struggled. We learn that Showalter’s mother was intrigued by Shirley Temple (hence her daughter’s name), but would never see a Shirley Temple movie in a theatre; that she wanted to become a writer, which became a dream deferred; that she was attracted to the glittery worlds of pretty clothes and acting on stage and being popular,

but instead became a plain Mennonite, wearing both a prayer covering and the cape dress, but only as long as the church commanded it.

The details Showalter lovingly provides about her mom—and then her dad, and then their marriage—creates a foundation for everything that will follow in her memoir, which itself focuses on Showalter’s family life. Like her mother, Showalter also experiences the tension between wanting to be part of the glittering

world and remaining in the conservative Mennonite world into which she was born—a tension that thematically unifies her memoir to its very last page.

In Blush, Showalter narrates what seems a mostly happily childhood in Lilitiz, Penn., relying on that dictum embraced by any good writer, showing us, rather than telling us, about her experiences. Through her careful detail, we can really know what it must have been like growing up the oldest child in a large family, living in a centuries-old farmhouse, attending public schools and longing to be recognized by adored teachers.

And also, what it must feel like to have a sister die weeks after her birth and watch a mother overcome by grief; or to witness a father struggle for acceptance in his own family; or even, more broadly, to negotiate what it means as a Mennonite teenager to be in the world, but not of it. Because Showalter covers this ground too, in Blush, acknowledging that even in a sweet life, there is some sour, which Showalter says is part of everyone’s childhood.

For Showalter, childhood was sweetest when surrounded by family, including the forty families in our church who called me by name and knew where I lived, what grade I was in, and what part I sang when we opened the hymnals together.

Her stories about this community—even its darker parts—are seasoned with a measure of grace, reflecting Showalter’s love for her people and her Mennonite upbringing.

Portions of Showalter’s memoir will be appreciated by those with similar Mennonite pasts. Blush will recall for some readers culture phenomena particular to ethnic Mennonites, as Showalter narrates her experiences with Walk-a-Mile (what she terms a Mennonite form of speed dating), with Mennonite meals, and with box socials. She alludes to hymns prized by Mennonite traditions, and to the rituals of worship with which many Mennonite readers will be familiar.

And yet, despite the specific Mennonite culture about which she is writing, Showalter’s Blush explores themes most any reader can appreciate, including the tension between individualism and community, learning to accept the past while living in the present, and struggling to stay grounded when the glittering world

is so alluring.

Showalter’s memoir succeeds exactly because of this: because she is able to take the particularities of her Mennonite upbringing, and make them widely understood through her narrative. This is—or should be—the mark of any great memoir, that the writer has taken her individual experience and made it universal.

In this way, Jean Janzen’s Entering the Wild: Essays on Faith and Writing also succeeds as a memoir, by taking the material of her life as a poet and a professor, and inviting us all as readers to enter in. Janzen, who now lives in Fresno, Calif., is already the author of several poetry collections, including most recently Paper House, published in 2008. Her work has appeared in a number of literary journals and poetry anthologies. Rudy Wiebe, considered by many a father of Mennonite letters, has said that Jean Janzen writes our songs,

praise both figurative and literal. Metaphorically, Janzen’s poetry inscribes the life of her people, the Mennonites; but Janzen has also written songs for a revised Mennonite hymnal, published in the early 90s, including Mothering God, You Gave Me Birth

and I Cannot Dance, Oh Love.

In Entering the Wild, Janzen narrates the process of crafting these hymns; and I found this chapter, titled Three Women and the Lost Coin: How Three Women Found Me,

the memoir’s most compelling. In 1990, Janzen was asked to be on a committee to recreate a Mennonite hymnal that might nourish . . . congregations for twenty years or more.

The committee, wanting to include several hymns honoring the feminine characteristics of God, turned to Janzen. Janzen describes encountering the work of three mystic women—Julian of Norwich, Hildegard von Bingen, and Mechtild of Magdeburg—and finding there the possibilities of devotion and celebration that opened windows to my own imagination.

Janzen wonders whether the Mennonite church would allow this medieval, yet fresh, language into our hymns,

and my inclination is to immediately respond to this question: I can’t imagine that they would. Yet Janzen unfolds her answer to the question, tracing her own journey through the medieval texts, revealing how the women’s writing opened up God—and her imagination—in new ways, and showing how the Mennonite hymnal committee gave Janzen a substantive gift she hadn’t even known she’d needed. Their gift to me,

Janzen says, was the opportunity to create out of the writings something I had not sought.

The chapter includes some lyrics for each of the three songs Janzen wrote, allowing us to read Janzen’s powerful reframing of the mystics’ texts, refracting their understanding of the feminine divine. She gives new voice to women speaking God’s love centuries ago. Janzen’s poetry here—and the story of its creation—expands our perception of God, renaming God for us; God becomes Root of Life, Eternal Vigor, Saving One, Moving Force, Mother. Mennonite readers will certainly notice the potentially subversive nature of her words and the risk taken to have them included in a hymnal used by most Mennonite churches.

Those seeking a comprehensive memoir will not find it here. At times, I hoped for something more: more story, more detail, more insight into Janzen’s life as a mother and as a poet. What we have are glimpses of Janzen’s life journey: hints at the challenges she faced as a wife to a successful medical doctor; flashes of insight into her development as a poet; and some connections, all too fleeting, to her Mennonite roots, primarily in Russia. Still, there is power in compression, and the beauty of lyrical prose. Entering the Wild is fundamentally poetry, and might well be read as such.

This is not the case for Saloma Miller Furlong’s Bonnet Strings: An Amish Woman’s Ties to Two Worlds, which tells a mostly chronological narrative of Furlong’s decision in the mid-1970s to leave her Amish community when she was 20 years old. Furlong’s story was recently featured in the PBS documentary The Amish: Shunned; there, she tells her story of leaving the Amish, then working with others who are also faced with the choice to remain Amish or seek another life.

After Furlong’s initial escape from her community—her leaving feels very much like a covert operation—Furlong travels to Vermont, a state she’s chosen because of the beautiful photos she views in Vermont Life. Once there, she finds room and board at a YWCA, meets women who soon become fast friends, and begins dating David Furlong, a Yankee

who makes and sells children’s toys. Several months later, Furlong finds herself back in her Amish community, trying to decide whether she belongs there—or whether the freedom she experienced in Vermont might be God’s will for her. A good portion of the book details her return to the Amish, and the cool reception she receives there as someone who has left and then returned.

Furlong describes trying to integrate herself back among her people, taking on a teaching position in an Amish school, baking goods for a market, attending church—and even, on one occasion, hosting church in the small house she has occupied when living with her family seems unfeasible.

Although she continues to communicate with friends in Vermont, and even though the man she dated there comes for a visit, Furlong feels, to a degree, committed to remaining Amish. Still, despite this commitment, Furlong seems a pariah within her community, ostracized by others and publically criticized by those who have leadership roles. Feeling a pull toward Vermont and away from the Amish again, Furlong must contend with the idea transmitted to her early and often in her childhood: that leaving the Amish will mean eternal damnation.

Bonnet Strings does an excellent job of exploring the tension Furlong feels between the pull of her community and her heritage, and the independence offered by the outside world. Recognizing she cannot have both her community and freedom, her religious heritage and the opportunity to be all God means for her to be, Furlong must make a heart-rending choice, covered in the memoir’s final chapters.

Although Furlong’s story is specifically about her experience attempting to straddle two worlds, she notes in the introduction that the memoir reflects a universal journey we all must make, choosing between our need for community and belonging and our desire for the freedom to walk the path that is most authentic to who we are.

While readers may not be able to relate to Furlong’s experience in an insular religious community, they will certainly connect to the larger ideas Furlong explores, as is the case in any well-written personal narrative.

Bonnet Strings is the second of Furlong’s memoirs. Her first, Why I Left the Amish, was published in 2011, and describes her return to her Ohio home for her father’s funeral, 24 years after she left. Reading the first memoir is not necessary to appreciate the second, although taken together, Furlong’s books provide an important antidote to the highly romanticized portrayal of the Amish to which many readers have become accustomed, given the current popularity of Amish romantic literature.

While the three women reviewed here are writing in the memoir genre, Robert Kreider’s Coming Home is very much in the vein of a traditional autobiography, covering his life from 1952, when he became an assistant professor at Bluffton College in Ohio, to 2011 and his retired years surrounded by family. Coming Home follows his first autobiography, My Early Years, which documents Kreider’s life as a child growing up in the Midwest, the son of a college professor; his time at Bethel College and in Civilian Public Service; and his marriage to Lois. Kreider concentrates his narrative in Coming Home on his years spent at Bluffton and at Bethel, with the final chapters devoted to his life after retirement, his travels, and his family.

In many ways, Kreider’s life exemplifies that of a Christian servant; and in his autobiography, his description of each decision made reflects his sincere desire to follow God’s leading. For example, Kreider describes the difficult decision he had to make in late 1959, when he was called to become president of Bethel College. He was only 40, had four young children, and had not served a long tenure in college administrative. Receiving an invitation to a college presidency was startling,

something Kreider had not anticipated. In his autobiography, he recalls his feelings regarding the offer: I needed divine help to disentangle my thoughts and feelings: the honor of it, the divine weight of it, the imponderables.

Although Kreider felt God telling him no

to the opportunity, the option of leading Bethel College returned early the next year. Again Kreider prayed; again, Kreider declined the offer. I am convinced I made the right decision,

he writes, noting that he did not feel equal to the task.

Coming Home makes clear that other vocational opportunities were likewise prayerfully considered, some easier to make than others. Indeed, the process through which Kreider made vocational decisions is a key component of his autobiography, something he returns to often in his text. As a highly valued leader, Kreider was often approached to take on work for different Mennonite organizations, and Coming Home details both the times Kreider assumed new leadership responsibilities, as well as the times when he prayerfully declined. Some readers will find this aspect of Kreider’s work to be most interesting, especially those invested in Mennonite organizational and missional history. For while Kreider’s life seemed essentially grounded in Mennonite institutions of higher learning, especially Bluffton College (where he eventually became president, serving from 1965-1972), Kreider also served in several capacities with Mennonite Central Committee and other mission organizations.

Woven into this narrative of Kreider’s public life are smaller stories of his private life, and of his wife and four children. It is clear from his work that Kreider’s home and family mean a great deal to him, and still, much as he wishes to turn away from his public self in parts of his narrative, the public and the private remain intertwined. Yet when he turns to his home life, Kreider seems his most animated, as in the chapter House in the Woods,

where he details his family’s purchase of two acres outside of Bluffton, describing as well the home they built and his children’s adventures there. He asserts that the house in the woods is for us a place of fond memory. Here we could express our creative impulses . . . it was a congenial place for a growing family.

And, Kreider writes, his wife Lois was the heroine who held things together

until they sold the farm after moving from Bluffton.

As Kreider’s autobiography comes to its conclusion, he reflects on his life journey, on the satisfactions of career

which fade away

while the joys of family deepen.

Here too, in this final chapter, Kreider’s voice is at its strongest and most reflective as he considers old age, his scattered family, and the ways he has been called to do kingdom work. Taken in toto, it’s clear that Kreider’s life, both public and private, has been a rich one, though even the concluding chapter of Coming Home—and the accompanying timeline—that the public life has served to shape and to drive the story Kreider tells about his life. This is not a critique so much as a recognition that Kreider’s autobiography represents a different type of text entirely, far different than the more reflective, tightly focused, and personal memoirs reviewed here.

Whether Mennonite life-writing is undergoing a larger paradigm shift, away from autobiography and toward memoir, remains less clear. The critical and popular success of Showalter’s Blush, and the appeal of Furlong’s Bonnet Strings as an authentic narrative of Amish life, suggest there might be a wider audience for life stories focusing more on the personal, rather than the public. And in the next year, several Mennonite memoirs will be published that continue the trend toward more focused, reflective, and creative works.

Still, what a text like Kreider’s Coming Home offers readers is the long view, an opportunity to know about Mennonite history as it was lived in a particular place and time, and from a particular perspective. Coming Home especially provides an excellent recounting of Bluffton College’s history in the mid- and late- 20th century, documenting a Mennonite institution in the crossroads, its leaders making decisions that would shape Bluffton into the school it is today.

In other words, there remains room on the bookshelf—virtual or otherwise—for both types of Mennonite life-writing, even if we remain a little unsure of what we should be calling these texts that help us understand, in different ways, what it means to be Mennonite. And also, what it means to be human.