Fig. 1: The Mennonite Settler in Newton’s Athletic Park on March 21, 2014. Photo: John M. Janzen

Fig. 1: The Mennonite Settler in Newton’s Athletic Park on March 21, 2014. Photo: John M. Janzen

Art that Works: Newton’s Mennonite Settler Monument in its 73rd Year

One hundred years from now my administration will be known for its art, not for its relief. — Franklin D. Roosevelt1

The greatest good a sculptor can perform is to create not for a museum or a private collection, but for the common meeting places of men. — Samuel Cushwan, artist.2

The tall still figure of a bearded man stands facing north on the circular drive in Newton’s Athletic Park. His face, in fact his entire front all the way down to the ripe wheat that encircles his feet, are overcast with charcoal gray mildew and blotches of dark lichen. (Fig. 1) But the Kansas Silverdale lime stone from which the Settler

was carved, gleamed a warm white in the early afternoon sunlight as I walked around him, away from his weather-darkened front. The synthetic material used by the conservators - major restoration was done about 15 years ago- to rejoin the seven limestone blocks that make up the whole figure is not affected by mildew and lichen, and therefore the joints show up like white horizontal bands across the dark mildew as I face the Settler

. On this day he looks as if he is tied with ropes – as the artist Christo might do, to call attention to a taken-for-granted significant site. But Christo’s wrapping of monuments is temporary, and so it should be with the mildew and mold that now blackens and threatens to corrode this sculpture whose work it is to keep the memory of our town’s and region’s history alive. I trust that the Settler’s

health-insurance plan will kick in shortly. The City of Newton is his custodian and with the honor of having the monument listed on the National Register of Historic Places (since 1998), the responsibility of its upkeep doubles. As they say: noblesse oblige.

The Settler

stands on a high pedestal, so I need to look up to him and to those he stands for, namely the thousands of immigrants who came to this region in the late 19th century. Their story is told in the four mosaic pictures at the sculpture’s base. There I read a mosaic ribbon of script: Commemorating Entry into Kansas from Russia of Turkey Red Hard Winter Wheat by Mennonites

. I see an onion-domed Russian Orthodox Church that stands for the Russian Mennonite immigrants’ home in the Ukraine region of Czarist Russia. Then there are three steam ships crossing the Atlantic to North America, waves of smoke billowing in long flowing silhouettes from their smoke stacks; then the picture story moves to a train pulled by a steam locomotive carrying the immigrants and their wheat to Kansas, and finally a small Kansas clapboard country church with steeple and a nearby farmstead, signifying the new home of the settlers. But other stories are embedded in the Settler

as well: its connection to President Roosevelt’s New Deal and his Federal Arts Project, which funded the monument in part; its artist; the hundreds of individuals who donated funds and labor toward the monument’s realization and its upkeep.

As I look at our Settler,

he and I are quite alone. An elderly couple walks past with their dog, their eyes fixed on the pavement of the road. He does not get much noticed at his spot in Athletic Park, though I have seen family reunion pictures on-line - sometimes clowning with hats on, sometimes assuming the Settler’s pose and wearing hats - in front of the Settler, where he serves as stand-in for the immigrant ancestors of more than a hundred years ago. For a moment, I think that a much more fitting space would be at the Santa Fe Train Station, where so many 19th and 20th century immigrants, and their wheat, arrived, and where that Turkey Red winter wheat is loaded and transported around the globe for nearly 150 years now. The Mennonite Settler

deserves to be seen by all the people living in and passing through town. But alas, for now he remains exactly where he was planted

by Newton civic leaders in 1942. I note that The Mennonite Settler

stands alone, yes, but he does also stand for thousands of others, women and men. And I note that in this representative role he is shown not busily working the land or harvesting, but in a moment of reverent repose. He has removed his hat and holds it in a gesture that humbly acknowledges a higher power that grants life. He makes me pause so that I might do likewise.

During October 2013 a spotlight was directed on The Settler

, albeit briefly, in conjunction with Kauffman Museum’s special exhibition Art that Worked: WPA Art in Newton, 1935-1943.

3 Brought together for the first time were works of art in Newton schools, Newton Public Library, and Bethel College that were created as part of the Roosevelt administration’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) for a visual art education collection to be used in schools. Since Newton’s only piece of public art funded in part by the federal WPA program could not be transported physically into the exhibition space, the Mennonite Settler

was brought into Kauffman Museum’s auditorium via word and image in a public lecture by this author.4 The audience numbered well over 100 persons who gave their undivided attention to the Settler

monument and its story – WAY more attention than the lone man is used to at his spot in Athletic Park, his back turned to the football stadium, and his face directed north across the street, a parking lot and a playground.

The Mennonite SettlerMonument: Patron and Artist Meet

During the summer of 1940, Newton’s Junior Chamber of Commerce, also known as the Jaycees – the group included three Mennonites businessmen5 – announced that it would sponsor the creation of a memorial to commemorate one of the greatest events in the history of the United States – the arrival of Turkey Red hard winter wheat in Kansas in 1874,

in the trunks of Mennonite immigrants from the Russian Czarist Empire. The Junior Chamber’s President Conrad P. Hinitt stated that this memorial, referred to initially as the Wheat Memorial

, was designed to recognize three distinct achievements: it was first dedicated to Bernhard Warkentin for bringing hard winter wheat to the United States from Russia and establishing the home of hard winter wheat in Harvey County; secondly the Santa Fe Railway for the important part it played in transporting the wheat overland and developing the great plains by settling pioneers; third, to the Mennonite people who settled in the area and toiled to turn the prairie into the richest wheat land in North America and to the many thousands of ethnically diverse people who made the production of wheat what it is today. To this I can add that in the winter of 2013 during a 4-months research sojourn in the Democratic Republic of the Congo I witnessed Kansas wheat being sold in the markets.

Keith Sprunger’s research shows that the Newton Jaycees fell a little short of meeting their goal to raise the projected cost of $2500, [so] the WPA agreed to pay for the remainder needed for materials and to bear all labor costs.

6 In a letter written to Reinhild Janzen on July 4, 1994, Max Nixon remembered … the project was undertaken in 1940 with a budget of around $500, that mostly contributed by a local miller…. The Jaycees set out to finance the project with contributions not only of money but also of wheat, and farmers from the wheat belt contributed by truck and bushel loads full. We feel,

President Hinitt said in a radio interview, that people who have benefitted for years from the growing of wheat and the processing of wheat will be willing to make that kind of contribution.

7

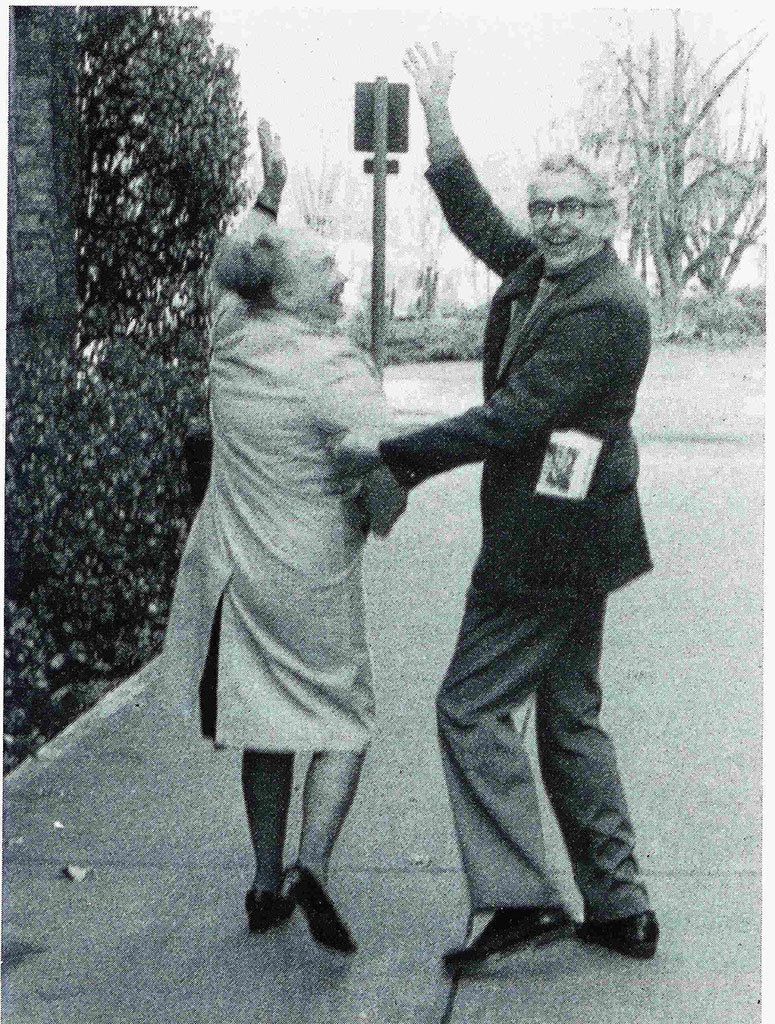

Fig. 2: Max and Hattie Mae Nixon, 1985, Eugene, Oregon, photo courtesy of Twenty Eight Years of Metalsmithing with Max Nixon, University of Oregon Museum of Art, 1985

Fig. 2: Max and Hattie Mae Nixon, 1985, Eugene, Oregon, photo courtesy of Twenty Eight Years of Metalsmithing with Max Nixon, University of Oregon Museum of Art, 1985Native Kansan Max Nixon (1915-2000) (Fig. 2) grew up on a farm at Haverhill in Butler County, attended Butler County Junior College, then graduated from the University of Kansas in Lawrence with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1939, where his formation as an artist would have been influenced considerably by the internationally renowned painter and writer Albert Bloch (1882-1961), chair of the Art Department. Nixon proceeded to teach at the Community Art Center in Topeka, which was a WPA project. Here, in 1940 and just one year out of College, the Topeka-based Federal Arts Project supervisor for Kansas, Verna Wear, tapped Max Nixon on the shoulder when the Jaycees contacted her for advisement for their ambitious monument plan.8 The Jaycees’ agenda as to what the Wheat Monument

was to communicate visually would have been a tall order for any artist to translate into imagery in a single monument. It was quite ingenious of Max Nixon to devise a multi-media work that combined sculpture and painting (as the mosaic medium is categorized). Unfortunately, Nixon’s initial drawings and plaster model for the monument that he would have had to have shown to Newton’s Junior Chamber of Commerce members for approval, have not survived to anyone’s knowledge.9 From the perspective of the 21st century, I have to wonder: had there been a woman member of the Junior Chamber of Commerce in 1940, might The Mennonite Settler

have been given a female partner to stand for the thousands of women toiling at their immigrant husband’s sides?

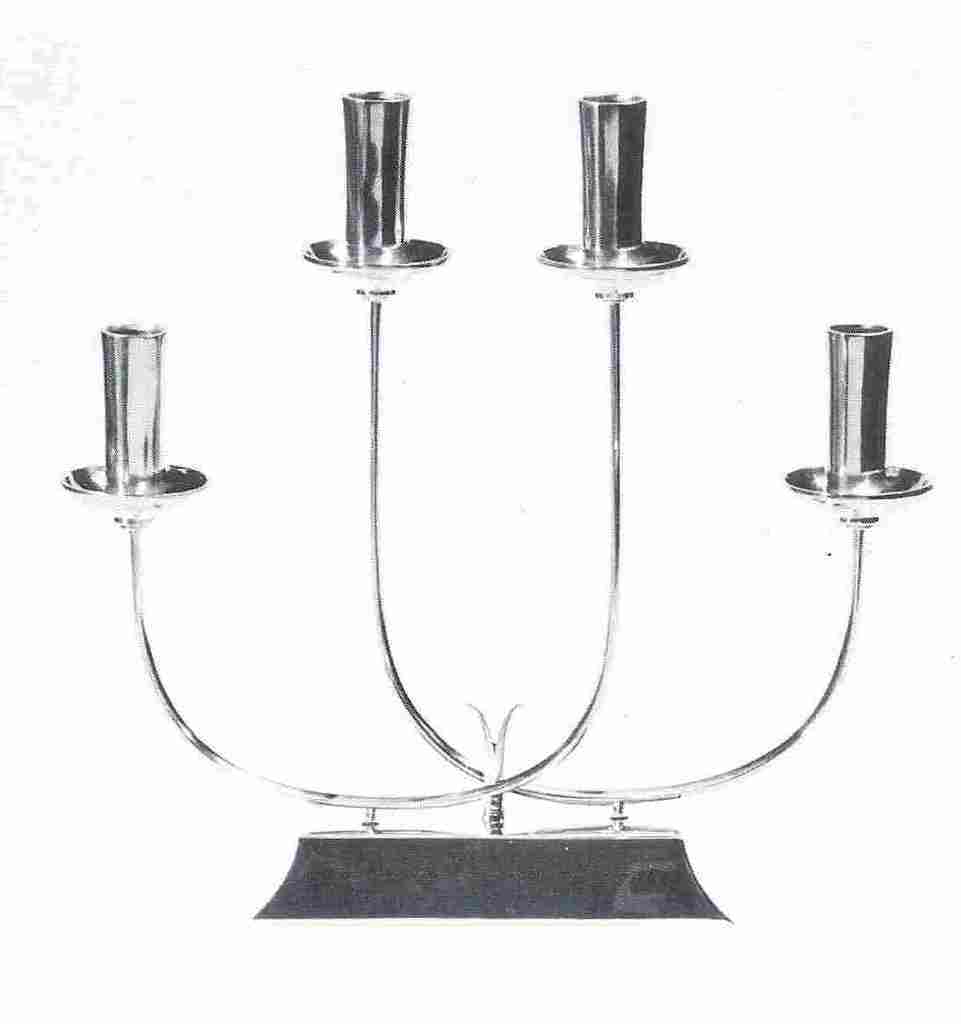

Fig. 3: Silver Candelabra, by Max Nixon, prior to 1985, photo courtesy of Twenty Eight Years of Metalsmithing with Max Nixon, University of Oregon Museum of Art, 1985

Fig. 3: Silver Candelabra, by Max Nixon, prior to 1985, photo courtesy of Twenty Eight Years of Metalsmithing with Max Nixon, University of Oregon Museum of Art, 1985By January 1941 the contract was signed, and Max Nixon went to work carving in the stone-cutting studio of the Sargent Cut Stone Co. on Adams Street in Topeka. Mr. Marsh, a Topeka contractor (famous for engineering many of the Marsh Arch Bridges in the Midwest) assisted with the design and pedestal construction. By June 1941 the sculpture was completed, but because of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States joining the allied forces in the war against Hitler, the artist Max Nixon was drafted to be a soldier, and thus the final installation of the sculpture in Newton’s Athletic Park, which also involved the fabrication of the mosaic base, was left to Newton-based stone mason Vernon T. Roberts. He used commercial colored ceramic tile - instead of the natural colored stones that Nixon had planned for - but followed Nixon’s original design.10 By 1941, the Federal Arts Project of the WPA was in the beginning of its waning phase as many of the artists either served in the US military, like Max Nixon, or they were needed for work in war plants for which their technical aptitudes particularly fitted them.

11 On Sept. 10, 1942, the Mennonite Settler

monument was dedicated with proper pomp and circumstance, including a printed program and a photographer sent from New York by Life magazine, but its artist-turned-soldier was away on duty. The Mennonite Settler

was to be Max Nixon’s first and last outdoor large-scale sculpture. He subsequently developed into a practitioner and teacher of metal craft, jewelry, and weaving, arts. He taught at the University of Oregon’ Department of Fine and Applied Arts for 28 years.12 When we look at the clean lines, the honesty with which the materials are handled, the spare and therefore elegant designs of Max Nixon’s works in silver, copper and bronze we can see the stylistic connection, the blood-relation

to his early work in stone, his Settler

. (Fig. 3)

According to Keith Sprunger’s findings, the Mennonite Settler

is one of about 100 surviving Kansas WPA public art projects - there are three other public sculptures, the rest are mural paintings -, and the only known monumental public sculpture of a Mennonite farmer in North America.13

Settler’sPath to Inclusion in the National Register of Historic Monuments

The end products of art in public places … are expressions of a community’s aspirations for itself, and of its initiative and persistence.14

The definition of the word monument

is a sculpture erected as a memorial, in Latin monumentum, its Latin root deriving from monere, to remind, to warn.15

November 19, 1992. Ann Becker sat down at her desk in her Wichita home to write a letter to Reinhild Janzen. Ann Becker was chair of Wichita’s Project Beauty Inc., which was chosen by the national Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) project to act as coordinating organization along with Wichita’s Public Arts Advisory Board to implement a comprehensive inventory of all public sculptures in Harvey, Butler and Sedgwick counties. She wrote to ask Reinhild Janzen, art historian and then-curator of cultural history at Kauffman Museum, to join this effort by acting as coordinator of an inventory of all of Harvey County’s public sculptures. This work entailed the location, evaluation, photography, research, and documentation of outdoor public sculpture.

Thus I began a ten-year-long involvement with the Mennonite Settler

monument as one of 25,000 volunteers across the United States who surveyed public sculpture in each county of the country, all under the auspices of the newly launched national Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) initiative, a joint project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art and the National Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property. To guide the work of the thousands of volunteer recorders of public outdoor sculptures, the National Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property published a very detailed Handbook in 1992. In addition, volunteer county coordinators received the SOS newsletter, called Save Outdoor Sculpture! Update.

16 I asked my colleagues at the Bethel College Art Department and two of my art history students to assist me in the task at hand.17 Of the eight public sculptures thus inventoried for Harvey County, the

Mennonite Settler

stood out not only because of its fame by association with the WPA Federal Arts Project, but also as the one public sculpture most in need of conservation. The completed questionnaire forms were submitted to the Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) offices in Washington DC to become part of a nation-wide inventory of public sculptures, a fundamental tool for the preservation of this part of the nation’s artistic heritage and identity. During the winter of 1993, Greater Wichita SOS! organized a symposium about the significance of public sculpture for the community and invited me to participate in a panel discussion whose purpose it was to feature area professionals and their respective organizations as they relate to public outdoor sculpture.

18 A training course for SOS! volunteers was held at the Wichita Art Museum on March 22, 1993.

November 12, 1993: Marike Janzen completed the Save Outdoor Sculpture questionnaire for the Mennonite Settler.

This was filed, along with the other completed questionnaires, with the Newton Public Library, the Kansas State Historical Society, and SOS! at the National Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property in Washington, DC. The first careful examination of the Settler’s

physical condition for the questionnaire’s condition report revealed a great deal of corrosion of the limestone, and the cracks in the mosaics were beginning to obliterate the figurative narrative (Fig. 4a). This was more damage than volunteers not trained in professional conservation practices could handle and the challenge became to raise funds for and to identify a professional sculpture conservator to rescue the Mennonite Settler

from slow but sure death.

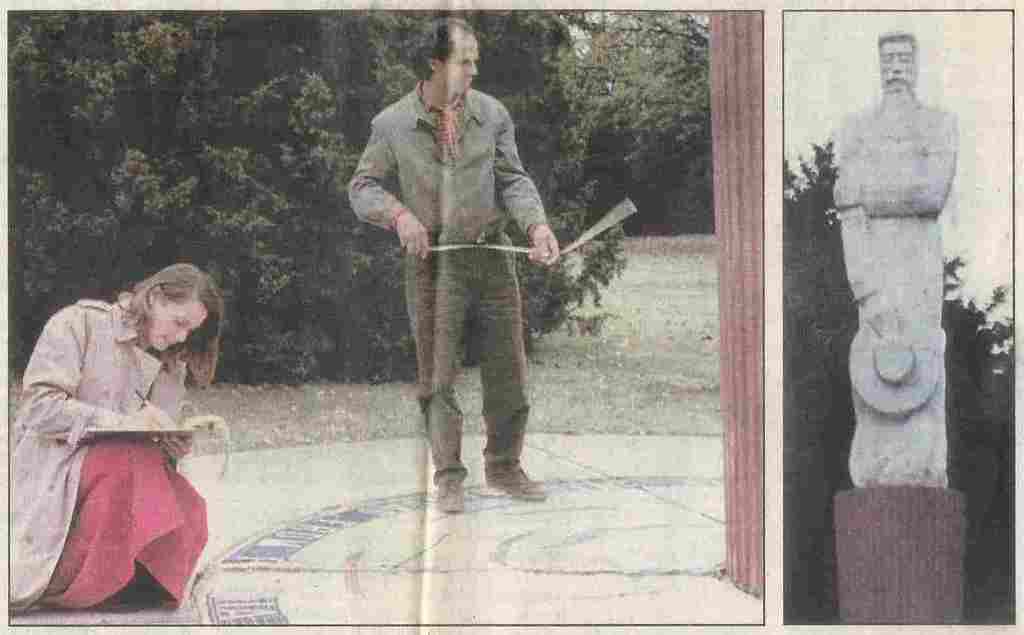

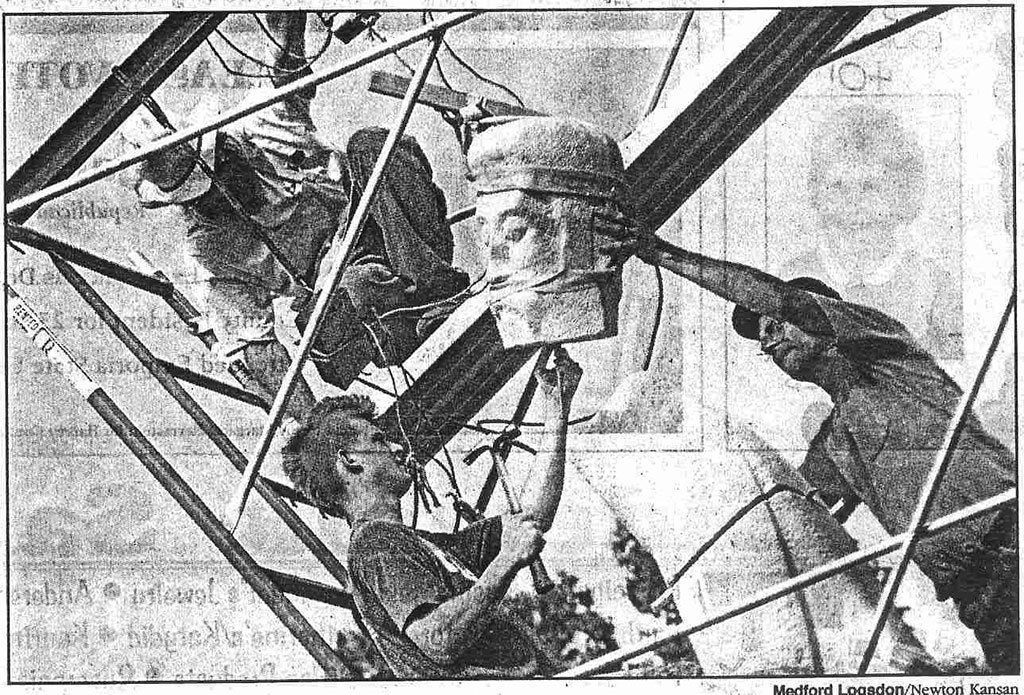

Fig. 5: Marianne Russell and Robert Marti assess the damage of the mosaic, pedestal and sculpture that comprise the Mennonite Settler monument, October 29, 1994, photo: The Newton Kansan, Oct. 31, 1994

Fig. 5: Marianne Russell and Robert Marti assess the damage of the mosaic, pedestal and sculpture that comprise the Mennonite Settler monument, October 29, 1994, photo: The Newton Kansan, Oct. 31, 19941994: The formation of an SOS! Newton committee of volunteers became a necessity if the Mennonite Settler was to be conserved so that it could continue its work assignment of warning, reminding

the people of Newton of their shared history. The committee’s purpose was to raise funds toward professional restoration of the monument. Representing the Harvey County Historical Society was Bethel College history professor Keith Sprunger, representing the Newton Fine Arts Association was pastor/sculptor John Gaeddert, representing the Newton City Commission was Beulah Day, representing Newton community residents and artists was Doug White, representing the Newton Convention and Tourism Bureau and the Kauffman Museum was Kathryn Gaeddert19, and as SOS! Coordinator for Harvey County and art historian I served as chair of the committee. Throughout this period The Newton Kansan was very supportive of the project, giving it good publicity.20 Upon my request the national SOS! Office in Washington, DC recommended three sculpture conservators and sent a video entitled Legacy at Risk: Strategies to Save Outdoor Sculptures.

I reported to the July 14, 1994, Newton Convention and Tourism Bureau Board meeting to secure seed money to bring in conservators to save the Mennonite Settler.21 This was granted and sculpture conservators Marianne Russell and Robert Marti of Russell-Marti Conservation Services, Inc., St. Louis, Missouri, (since 1995 in California, MO) were selected and contacted by the Newton SOS! Committee and invited for a thorough inspection of the damage that had been caused by natural weathering, a non-original layer of white paint, mechanical damage (chips, spalls, cracking, and natural weathering (water damage and organic growth) as well as occasional vandalism (Fig. 5). Thus the front page headline of The Newton Kansan read on Oct 31, 1994: The Settler badly in need of repair

next to a photo of Marianne Russell and Bob Marti at the site of the Settler

making a thorough study and recording of all the damages. Their bill for their October 29 site visit for examination and preparation of a conservation treatment proposal was $550. The Newton Convention and Tourism Bureau named the Settler

Attraction of the Month of December 1994.

1995, 1996: Things began to move forward. In March of 1995, impassioned by my mission for preserving The Mennonite Settler,

I chaired a session I had organized on Art in Public Spaces: Where, Why, What, and Who Cares?

at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Art History Society in St. Louis, Missouri. On April 25, 1995, Russell-Marti conservators submitted their Examination Report and Proposal for Conservation Treatment

of the Mennonite Settler

with a projected cost of $40,400. On July 18, 1995, representatives of the SOS! Newton committee pleaded the case of the Settler monument’s restoration needs before the Newton City Commission, for monetary support.22 They argued that restoration would halt the deterioration process, that it will bring the monument back to an appearance appropriate to the original artistic intent, the age, and the history of the piece, and that it will prevent continuing, accelerated deterioration of the monument.

23 The City countered that it wanted to see the SOS! Newton committee raise some funds on their own before the City would consider appropriation of funds toward this project. By the time of the next appearance before the City Commission, the SOS! Newton committee was in a much stronger position to ask for money: by now nearly $5000 from private funds had been raised and the application to put the Settler

on the Register of Historic Places had been filed in Topeka.

The route toward success in obtaining financial support from the City of Newton, the monument’s legal owner, from grant and matching funds requests from state and private foundations, institutions affiliated with the Mennonite conferences, regional businesses and from private sources in the Newton community had to lead via the Mennonite Settler’s

acceptance and official registration on both the state and the national registers of historic monuments. Its historic and artistic significance had to be convincingly argued and proven.24 If Washington and Topeka thought the sculpture was worth saving, then the local community would be encouraged to contribute financially to the project. I proceeded to write the application draft (officially called National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

) for listing the Settler

on the National Register of Historic Places and submitted it to the Kansas Historic Preservation Office of the Kansas State Historical Society on April 2, 1996. This process subsequently involved my appearance in front of the Kansas Historic Sites Board of Review in Topeka on August 23, 1997, to defend the nomination. The Board voted then to nominate the monument for the national register.

Fig. 6: Dudley Toews as the

Fig. 6: Dudley Toews as the Mennonite Settlervisits a fourth grade class at Northridge Elementary School. Kiley Smith listens attentively. April 26, 1996. Photo: The Newton Kansan

Parallel to the SOS!, Newton fund-raising work was that of educating the public about the importance of public sculpture in Newton in general and the Mennonite Settler

in particular. Several initiatives were organized in Newton to raise awareness. For example, Doug White of the SOS! Newton committee worked with LaDonna Unruh Voth, Newton art teacher, on a program/skit for elementary schools to teach the history and meaning of The Mennonite Settler

, Skipper,

and the fountains at the Carriage Factory park and Bethel College. Dudley Toews was asked to assist with classroom presentations where he appeared in costume as the Mennonite Settler

monument, telling its story25 (Fig. 6). A community-wide sculpture walk

called Celebration and Preservation: a tour of Newton’s Outdoor Sculptures

was organized for Sunday May 26, 1996, in conjunction with National Preservation Week.26 This event culminated with a reception - and opportunity to donate money towards The Settler’s

restoration - at the Carriage Factory Gallery. I have a vivid memory of visiting Lloyd Smith in his office in the Old Mill and asking him to kindly contribute to the cost of the reception refreshments. He kindly obliged.

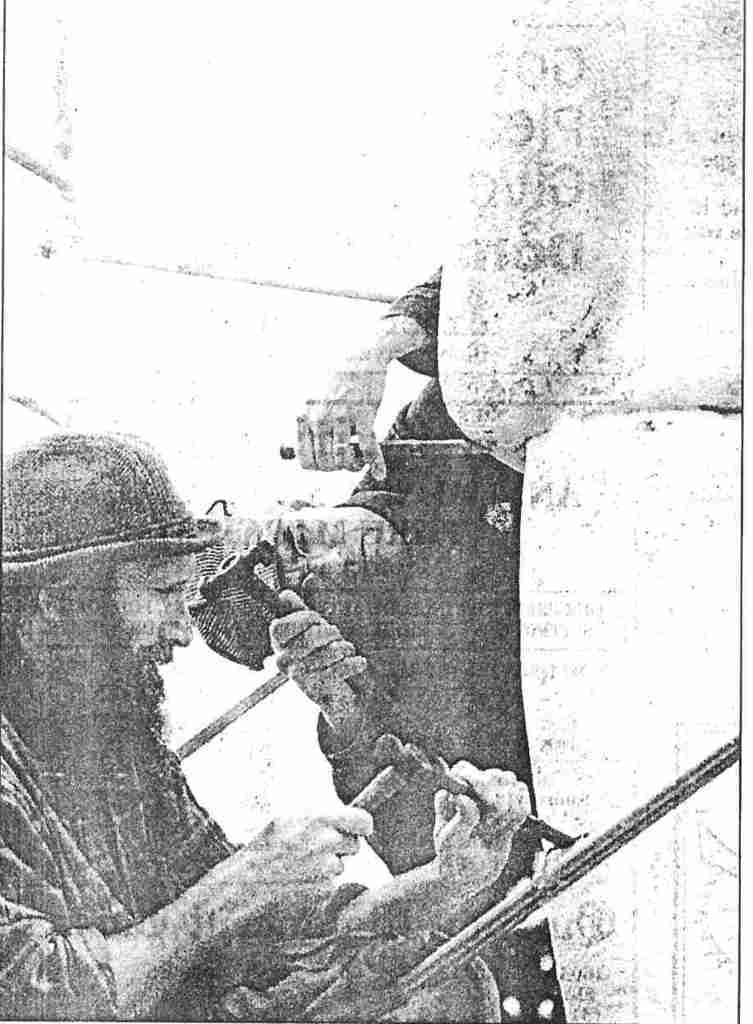

Fig. 8: Vince Gallo (left) and Bob Marti takes the sculpture apart. Photo: The Newton Kansan , Monday March 30, 1998

Fig. 8: Vince Gallo (left) and Bob Marti takes the sculpture apart. Photo: The Newton Kansan , Monday March 30, 1998Monday, March 24, 1997. The front page of The Newton Kansan shows the Settler

vandalized with disfiguring large black spray painted graffiti in the form of pentagrams –occult symbols27 (Fig. 7). In a related case of vandalism, discovered by SOS! Newton committee member John Gaeddert28, the head of the Settler had been damaged and had become precariously loose. Conservator Robert Marti was asked to come in order to remove the graffiti and to repair and secure the Settler’s head, and the City of Newton footed the bill (Fig. 8). It is on June 3, 1997, that the Newton City Commission allocates $30,176 for the restoration of the sculpture, matching the $10,224 raised by the Newton SOS! Committee.29

Friday. March 27, 1998: A photographer from The Newton Kansan is on the scene as Bob Marti and assistant Vince Gallo take The Settler

apart with chisel and hammer and load up the seven lime stone blocks and the four sections of mosaic painting for transport to the Russell-Marti Conservation Services Inc. in California, Missouri. In the same year, the Settler

is officially nominated to the National Register of Historic Places for its association with the Works Progress Administration (WPA)30. So, the necessary funds are finally in hand and Russell-Marti Conservators can be invited to begin their work.

Fig. 9: Re-installation of The Mennonite Settler monument, Bob Marti and assistants Vincent Gallo watching and Enoch Simpson placing bolt in the head of the

Fig. 9: Re-installation of The Mennonite Settler monument, Bob Marti and assistants Vincent Gallo watching and Enoch Simpson placing bolt in the head of the Settler. July 27/28, 2000. Photos: The Newton Kansan

Fig. 10: Dedication of the restored monument, the moment of the unveiling, Sunday, October 1, 2000. Photo: John M. Janzen

Fig. 10: Dedication of the restored monument, the moment of the unveiling, Sunday, October 1, 2000. Photo: John M. JanzenJune 2000: Russell-Marti has completed its restoration of the monument. In July Bob Marti drove it back to Newton and re-installed it on its original site in Athletic Park31 (Fig. 9). In preparation, the site had received improvements toward greater safety of the mosaic painting. Newton’s Parks and Recreation Department constructed a new cement base with better drainage on which the now restored mosaic surrounding the sculpture and its cast cement pedestal were placed (Fig. 4b). The initial placement of the mosaic had been level with the surrounding side-walk, which could not prevent pedestrians and bicycles from moving right across the mosaic and causing damage. Now the mosaic is raised by one foot, and the new circular base is in turn surrounded by low plantings. This affords quite a bit of protection. John Gaeddert, Keith Sprunger and Raymond Olais volunteered to repair holes and gouges in the sculpture’s ridged, cone-shaped 7 feet tall pedestal prior to the re-installation of the mosaic and the Settler

sculpture. With all of this done, a celebration was in order. On Sunday, October 1, 2000, a beautiful sunny October day, the re-dedication of the restored sculpture was held, complete with Mike Jones’ High School Brass Ensemble, a Welcome by Reinhild Janzen, Recognition and Remarks of Supporting Organizations which included Mayor Carl Harris, Shelley Keith of the Newton Area Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau, and David Haury of the Kansas State Historical Society. Keith Sprunger spoke on the history and significance of the Mennonite Settler

and the program culminated in a dramatic unveiling of the restored monument (Fig. 10). The program leaflet’s list of acknowledgements bears testimony to a truly impressive coming together of private and public partnerships in support of the monument’s restoration, including Mennonite congregations in Germany32, the Schowalter Foundation, and six Bethel College Mennonite Church Sunday School classes.33

But, the work was still not complete. Now that the monument was in place again it became evident that it was not entirely self-explanatory for the uninitiated observer and the SOS! Newton committee decided that The Mennonite Settler

site needed an interpretive sign, something that it had never had before. The logic being: if we understand the Other

we have greater appreciation for the Other

and therefore are also less prone to negligence or defacement. A succinct text was written by Keith Sprunger and Kauffman Museum designer Chuck Regier installed the sign in 2001. Thus it was that it took nearly 10 years to restore the Settler

to its important work as keeper of a significant chunk of Newton’s and its rural surroundings’ settlement history of the late 19th century.

Settlerin the context of other monumental WPA art

A number of Federal Arts Project works for public spaces featured and celebrated Kansas as an agricultural state. The theme of wheat that is central to the Settler

is also the subject of five out of twenty-five murals painted in 25 towns across Kansas between 1936 and 1942.34 Examples are the wheat harvest scene entitled Men of Wheat

by Joe Jones in the post office of Seneca, painted in 194035, or Dorothea Tomlinson’s 1938 Wheat Center

mural in the post office of Hoisington. Of the four public sculptures sponsored by the WPA’s Fine Arts Section in Kansas, the The Mennonite Settler

is the only one whose theme concerns the farming of wheat.36

In 1936, the WPA’s Federal Arts Project reported the total number of artists employed at 5257, and while mural painting employed the highest number of artists at 955, the sculpture division employed 469 sculptors.37 One of these was our

Max Nixon. Additional art producing divisions of the WPA’s Federal Art Project included Practical Arts,

which involved the making of posters, arts and crafts, photography, stage sets, dioramas, and visual models; an arts education division which supported art teaching, art centers and galleries, and research; and the category Miscellaneous

which supported technical workers and craftsmen, artists’ models, laborers such as framers, project coordinators, directors and more. When evaluating the impact of the Federal Arts Project from the vantage point of the early 21st century – or 73 years after the FAP’s conception and implementation in 1936– Victoria Grieve concluded that its most important legacy might well be that the Federal Arts Project set a precedent for government involvement in the arts that continues to this day.

38 Newton and North Newton have benefitted from arts and humanities funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities to this day.

To appreciate Newton’s Settler

in the context of comparable monumental WPA sponsored sculpture we might take a look at Donald Hord’s Guardian of Water

, a fountain placed outside of San Diego’s City Hall (Fig. 11). Here, a native Indian woman carries a jug of water on her shoulder. She personifies water as most precious source of life but also re-enacting the daily chore – simultaneously mundane and sacred - of carrying water to the home from the water’s source.39 Just like the Settler

stands for thousands of others, so does this water carrier. Her body language too, like that of the Settler

is of great dignity, albeit it emphasizes action rather than the Settler’s

inward directed contemplation. When Hord carved the woman who crowns the fountain from a 13 feet high granite block, he was already a much experienced and accomplished sculptor, whereas Nixon was but a novice one year out of college, whose conception and execution of the Settler’s

story from blocks of native limestone and natural colored stone mosaic must be seen as a considerable act of inspiration and courage.

The features of the bearded man and his clothing are simplified, or rather, essentialized to such a degree that the figure is clearly not to be understood as a portrait of a specific person. There are no indicators of a particular age, social rank, or attributes that would place this man in a specific time or place other than the plot of earth on which he stands, which offers up ripe wheat ready to be harvested which in Kansas is the month of June. In this way, the figure stands for every immigrant who came to grow and to market food in Kansas. The man has taken off his hat and holds it in front of him, while his left arm clasps the right across his chest. That makes for a very still, self-contained stance, a closed monolithic form, reminiscent of Egyptian funerary sculptures or Greek kouroi, which also share this figure’s absolute frontality. The Settler

stands with his weight balanced equally on each leg, perfectly erect. This is not a relaxed or at-ease pose. He stands as it were with utter concentration on thought, on prayer. His eyes are downcast, that is, inward-directed. His body language is that of respect for another being. A hat is taken off when greeting someone, when speaking with another, and most certainly for prayer when in the presence of God. The Settler’s

pose is one of reverence, of humility, a stance we can all identify with and have assumed ourselves when we acknowledge the higher power that gives life. Max Nixon said in a letter to Keith Sprunger that he wanted to portray in this sculpture his own reverence for these people, for their tribulations of the past and their bringing of the wheat to Kansas.

40 The Settler’s

reverent pose and calm steadfastness invites us to pause, to be still for a moment, to be grateful for the vision and the work of those who came before us and to be thankful for our daily bread.

Almost Spring. The sun is bright, the sky is blue, and this afternoon the Settler

looks out toward a busy children’s playground in the park, filled with happy noise, but none of the children or their parents pay him a visit. An elderly couple is seated in their parked car, eating a treat of ice-cream. Their backs are turned to the Settler

because the way parking is prescribed at this spot. However, a quick online check under Mennonite Settler Statue

reveals that he gets a lot of attention in the digital reality of the world-wide web. Google tells us that some 730 people have checked out his picture, he is featured on the sites of Wikipedia, Wikimedia, and Yahoo travel, he gets liked

on Facebook, and even the black and white photos of him that a young Life magazine photographer took at the 1942 dedication ceremonies are right there on the computer screen. His limestone body gleams a brilliant white in those pictures. Though today, 73 years after his coming-into-being, the Settler

looks a bit frightening. Long hard winters since his cure

in 2000 have turned his weathered north-directed front even darker, almost black, than it was a few months earlier. It is really high time that Newton City workers administer a life-preserving removal of mildew and lichen which eat away at the soft lime stone.41 Still, the Settler

continues his work. The work of art is to keep memory alive, or, the work of a work of art is to prevent loss of memory. Newton’s Settler

accomplishes this if we take a moment to look at him with understanding.