1894 Flag of the United States

1894 Flag of the United States

Americans by Choice: Reflections on Immigration and Citizenship from a Mennonite Perspective

What business do I have talking about immigration, when I’ve lived 98 percent of my life in the ZIP code where I was born, and part of the other 2 percent in the bordering ZIP code just to the north? Despite the fact that I haven’t drastically changed my place of residence all that much in the last 54 years, I think my life experience of immigration and international connections is unusual – not the norm among my generic American friends and acquaintances growing up. So I’ll offer you a not entirely coherent set of stories and opinions linked to immigration and citizenship.

Back in 2010, an exhibit designer contacted me looking for material to represent Mennonites as one of many known immigrant groups in Kansas as part of an exhibit she was preparing for the U.S. District Court of the State of Kansas for the court’s 150th anniversary commemoration. The federal court oversees citizenship and naturalization matters in Kansas. She wanted something that would make a coherent package – naturalization papers, photos, basic narrative of the persons.

We have a good number of such documents in the Mennonite Library and Archives. Two-thirds of the first 50 personal papers collections, for example, were created by immigrants, and most of the other one-third were created by second-generation immigrants. But what seemed easiest to put together into a complete package was from my own family. Initially, the exhibit designer was thinking of the Mennonite immigration of 1874 and the following several years, which meant my Thiesen ancestors. But at some point, either I or she raised the question of later Mennonite immigration, which led to my mother’s family and the small numbers of post-World War I Mennonite immigrants to Kansas.

Much of this material ended up being included in the exhibit. The 1874 material is my father’s side – the Thiesens and Goertzens. There’s probably less to say here than for my mother’s family for several reasons: It’s farther in the past, so I didn’t know the immigrant generation personally. They didn’t leave behind much writing (or any at all) and weren’t talkative storytellers who could inject oral traditions into the family culture to be handed down. And their experiences were more prosaic. They farmed in Russia, they came over here and they farmed here. What more is there to say?

All four of my great-grandparents on my father’s side, his grandparents – Heinrich Thiesen, Anna Goertz, Heinrich Goertzen and Anna Schmidt – came on the Cimbria, arriving Aug. 27, 1874, in New York, all about 10 years old, with parents and siblings.

There were close to 600 Mennonite passengers on the ship. Most of them, including the Thiesens and Goertzens, became part of the new Alexanderwohl Mennonite congregation a few miles north of North Newton, in Goessel. And many of their descendants have stayed in central Kansas over the next nearly 140 years. These families had been in Russia – now Ukraine – for only 70 years, coming there from the Vistula Delta region. So these lineages have been in Kansas for twice as long as they were in Russia.

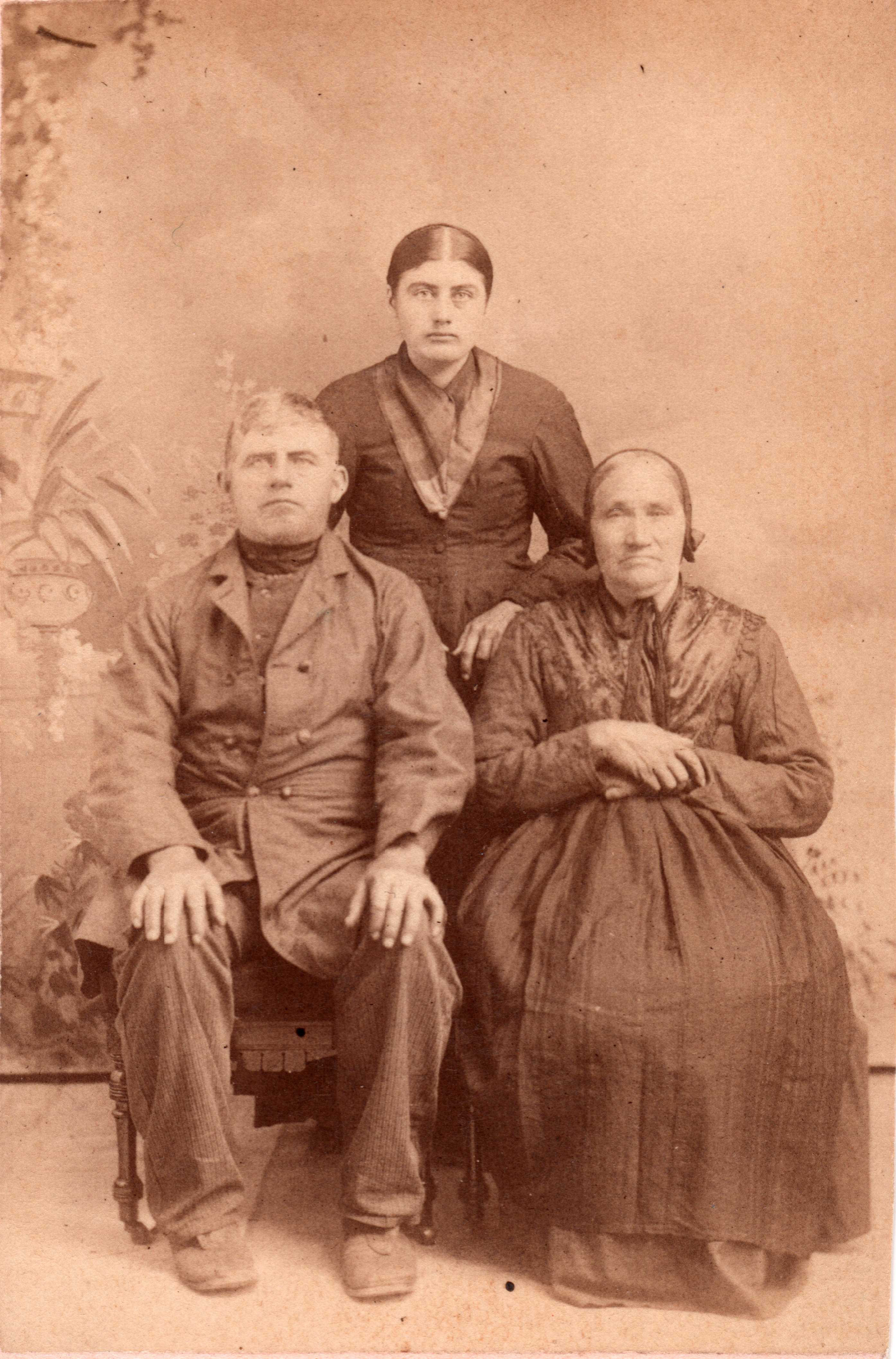

This is Jakob Thiesen, Katharina Block and their daughter (oldest child) Helena. The photo was taken in the early 1880s by Mrs. B.F. Denton in Newton.

This is Jakob Thiesen, Katharina Block and their daughter (oldest child) Helena. The photo was taken in the early 1880s by Mrs. B.F. Denton in Newton.This is Jakob Thiesen, Katharina Block and their daughter (oldest child) Helena. The photo was taken in the early 1880s by Mrs. B.F. Denton in Newton. There is another photo of the boys.

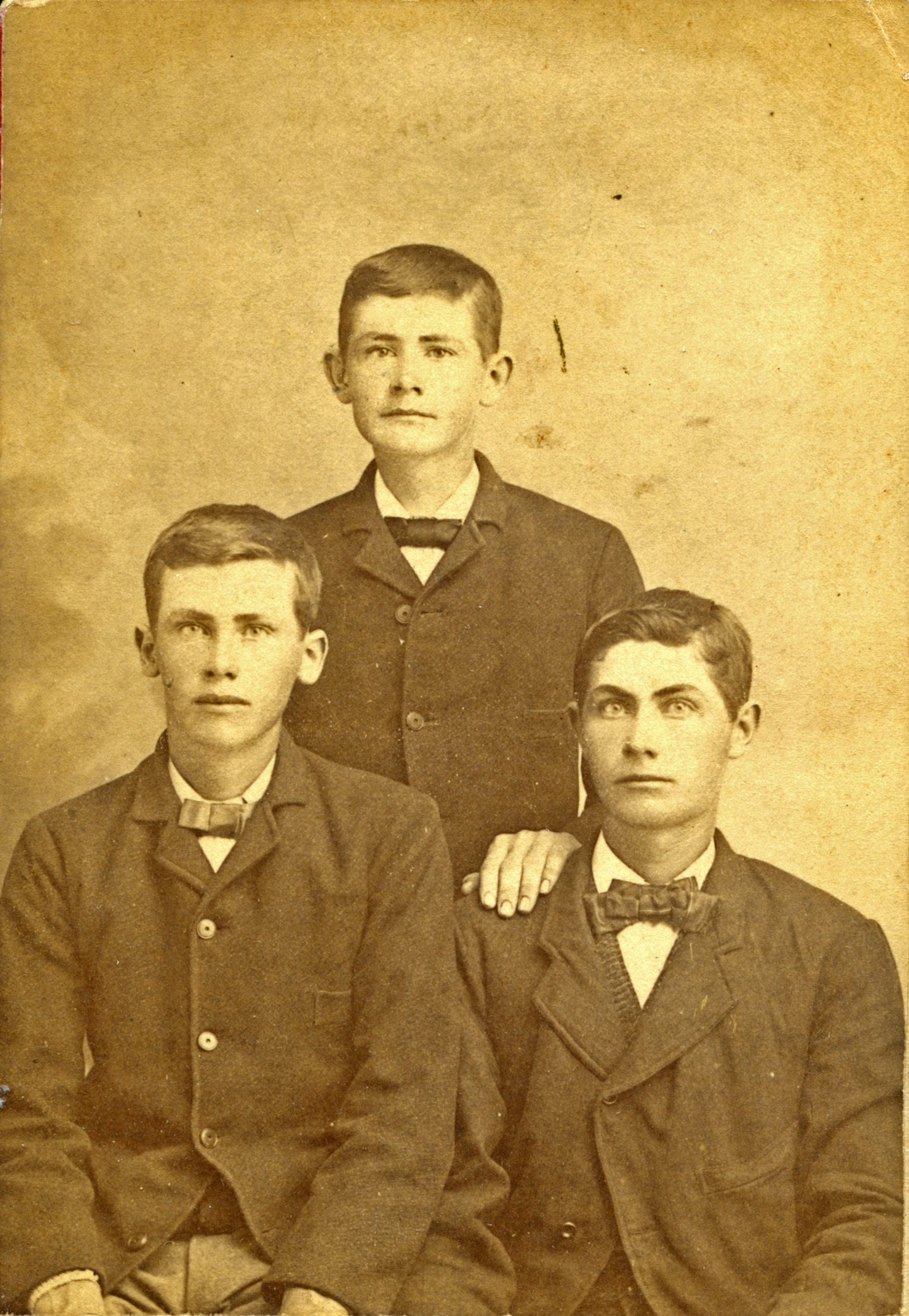

This is David, Jacob B. and Henry Thiesen, probably taken on the same visit to the photographer. Henry is my direct ancestor

This is David, Jacob B. and Henry Thiesen, probably taken on the same visit to the photographer. Henry is my direct ancestorThis is David, Jacob B. and Henry Thiesen, probably taken on the same visit to the photographer. Henry is my direct ancestor.

As I hinted before, we don’t know that much about these people beyond names and dates. They didn’t leave much in the way of written documentation or oral tradition.

As far as we know, Jakob or Jacob, the father, had no siblings who lived to adulthood or married. We have names for three sisters, but no indication of their death dates or any families. Jacob’s father had the unusual first name of Isbrandt. Isbrandt had migrated from Prussia, near present-day Malbork, Poland, to Russia in 1804. And then his son, as an adult, moved on again. Isbrandt apparently got into a dispute at some point with the famous Johann Cornies, but I don’t really know the story behind that. Isbrandt didn’t migrate with his son; he died in 1883 in Russia. That’s about all we know about him.

Isbrandt’s son Jacob is reported to have liked to ride and drive fast; it was said he liked to go to Cresswell, south of Hillsboro, Kansas, about 10 miles from his home, to get groceries or other supplies, presumably for the chance to ride or drive. It’s said that he planted a lot of fruit trees on his farm northeast of where Tabor Mennonite Church is now.

Jacob died in 1911. His wife, Katharina Block, seems to have had two sisters who were also on the Cimbria, but no other siblings. Katharina died in 1898 and was buried in the Alexanderwohl cemetery, but Jacob was one of the early burials in the Tabor cemetery, closer to their home place.

Of Jacob and Katharina’s four children, only two married, Henry (my ancestor) and Jacob B. The daughter Helena died in 1908 at age 48 and was the first burial in the Tabor cemetery. The other son David was somewhat of an eccentric. My dad’s generation knew him as “Ohm Doft.” There is a photo of him with an elaborate construction, apparently for pumping water. He also traveled more than the others, spending some time in California working in the orchards, documented by some letters he wrote home from there.

Jacob’s “declaration of intention” filing is dated 1877 – the beginning of his citizenship process. Probably the justification for this was to be able to vote in local school elections. The early plat maps show a school located on Jacob’s land in Marion County, Kansas. It’s interesting that this was done in Newton, in Harvey County, even though he lived in Marion County. Jacob’s final citizenship form is dated 1894, 17 years later, and it was in Marion County. I’m not sure why it took that long. I don’t think the time lapse was required. Maybe he just didn’t get around to it sooner.

I also have Henry’s citizenship papers (or rather, my cousin Mayleen does), his declaration of intention filing in 1885 in Marion County when he was age 22. Interestingly, it indicates he affirmed rather than swore to the conditions of the document. His final papers are from Harvey County in 1899, 14 years later. Here there isn’t any mention of affirming.

Henry had only two children who lived to adulthood and only one of them married. Henry’s brother Jacob B. had three adult children, two of whom married. So these families remained unusually small compared to the average for their community. As I said, many of the relatively small number of descendants remain in central Kansas but some are scattered from Pennsylvania to California to the Dominican Republic.

My mother’s family – Kroekers, Janzens, Langemanns – came from the same context as the Thiesens and Goertzens but they were among the majority who stayed in Russia (Ukraine) in the 1870s, for another 45-50 years. They were among the Mennonite industrialist class by the early 20th century, and had participated in starting Mennonite villages in Crimea, south of the original Mennonite colonies. There are a lot more stories and traditions available for these families, partly because they were a couple of generations closer in time to me, partly because they wrote more and told stories more, and partly because many of their experiences were more traumatic and unusual.

My great-grandfather Jakob Kroeker was the famous one in the family. He had wanted to be a missionary to India, but health issues apparently prevented that. Right after marriage to Anna Langemann, he attended the Baptist seminary in Hamburg, where my grandfather John Kroeker was born in 1894.

Jakob became a traveling evangelist for the Mennonite Brethren back in Russia and was successful enough to expand his work into non-Mennonite circles. His ecumenical mindedness caused tensions with the MBs and he turned his attention to wider pietistic/revivalist circles, including many contacts among Russian elites in St. Petersburg.

In about 1910, Jakob decided to move his family to Germany. It’s not entirely clear why; apparently he felt he would be freer to carry out his religious activities there than in Russia. He moved to the Harz region, which was the center of some of the revival movements that influenced him (Blankenburger Allianz), so it may have been a move to be closer to supporters. There, in Wernigerode, he and other Mennonite and non-Mennonite supporters soon started a Bible school to train church workers for Russia and other areas in eastern Europe. Jakob became fairly widely known even outside Mennonite circles as an Old Testament expositor.

My grandfather John Kroeker thus spent his later school years in Wernigerode. Shortly before World War I, John returned to Crimea to work in the office of his Langemann grandfather’s factories. With the beginning of the war, he was drafted into the Russian military and served first in the medical service in the Caucasus (he wrote about being on the slopes of Mt. Ararat) and later became what sounds like the manager of a whole chain of PX shops on the European front. Here he seems to have had a lot of contact with high-level officers and political leadership, maybe capitalizing on his father’s earlier contacts.

With the end of the war, John was back in Crimea. He and Katherine Janzen were married in 1918, in the midst of the Russian civil war.

It was a double wedding. Katherine married John and Katherine’s sister Liese married John’s uncle Kornelius Kroeker, his father’s younger half-brother. (It gets more complicated: another Janzen sister, Anna, later married Kornelius’ brother Peter Kroeker, and still another Janzen sister, Gertrud, married Hans Langemann, who was also John Kroeker’s uncle. John reportedly used to say he could chart out how he was his own grandfather.) The Janzen sisters also came from the Mennonite industrialist class, but their family traditions haven’t survived very well. My grandmother, for example, didn’t even know the names of her own grandparents.

Shortly after the wedding, a life of multiple migrations began. John (or Hans) became some kind of local official for the village where they lived, mayor or clerk or something. Such officials were rounded up by one of the revolutionary factions who occupied the area. My mother was born at the beginning of August 1919, and this round-up of officials must have been in late October. So these men were marched off to some destination for questioning.

On the way, my grandfather gradually hung back and managed to run off into the darkness. Since he knew his way around the area, he found a friendly hiding place and made his way back home to get his wife and daughter. They went to the port, Sevastopol, where he paid their way across to Istanbul on an American freighter with furs and tobacco. From Istanbul, they made their way eventually over several months to Wernigerode. They apparently traveled some with other refugees from Russia, since my grandmother talked about wearing a coat with someone else’s jewels sewn into it, riding on the Orient Express to Vienna.

They spent the next six years, more or less, in Wernigerode and Berlin. My uncle Jake was born in Wernigerode in 1921. Presumably Hans did work in connection with his father’s Licht im Osten Bible school. During the time the family lived in Berlin, Hans apparently worked some of the time for the firm of Fast and Brilliant, a partly Mennonite-owned (Fast) exporting company that sent relief packages to Russia donated from Germany and elsewhere. (Since Brilliant was Jewish, I’ve wondered what happened to him in the long run.)

The period living in Wernigerode was a major happy childhood memory for my mother, something she often referred to – living in a big household with her grandparents, lots of uncles and aunts (her youngest uncle was only about four years older than she), lots of visitors and activity connected with the Bible school and mission.

In 1922, my great-grandfather Jakob came to North America for a speaking tour to promote his school and mission work. He’s listed in the Ellis Island database, arriving May 13, 1922, on the ship America coming from Bremen. The family story that I had always heard was that Jakob’s son Nick, my grandfather’s brother, who would have been about 20, came along with him as sort of an assistant. But the Ellis Island database doesn’t support that. It says that Nick arrived Dec. 23, 1922, on the ship George Washington and that his contact in the United States was Cornelius Claassen in Newton (that was the Claassen banking family).

Jakob had been in Newton on his speaking tour, and the Claassens were apparently supporters of the mission, since there is a photo of them visiting in Wernigerode. Nick got a job as a bookkeeper with the Railway Ice Company in Newton, maybe with the help of C.F. Claassen. This was the period of runaway inflation in Germany, so presumably Nick thought his job prospects were better here, or maybe he just wanted to get away on his own.

In 1926, my grandparents Hans and Tina Kroeker and their two children decided to follow Nick to the United States. As far as I can tell, this was an economic decision. Their years in Germany were a time of economic and political chaos and maybe they felt that since Nick had been reasonably successful, there might be a better opportunity here.

I also have to wonder, however, to what extent the move maybe was prompted by a desire to get away from conflicted relationships. To speak in present-day terms, I wonder if both my Kroeker grandparents suffered from PTSD because of their experiences of the Russian revolution and civil war as young adults. If Hans had been living in recent decades, he would likely have been in an alcoholism treatment program. (As it was, his problems were just condemned by those around him as a moral failing.) At least a couple of Hans’ brothers had similar issues throughout their lives. Tina had a variety of not-very-specific emotional and physical health problems all her life.

.jpg) J. Braun2

J. Braun2In any case, Hans and Tina’s migration to the United States in 1926 offers somewhat of a puzzle. My mother had vivid memories of passing through Ellis Island. The problem is that Ellis Island ceased to function as a general immigration facility in 1924. After new immigration legislation was passed in that year, most of the paperwork and inspection functions that had been done there were now done at U.S. consulates before people embarked for the United States.

I don’t quite know what to make of this, but this seems to be the most likely explanation: Apparently, Ellis Island continued to be used for immigration cases where there was some kind of paperwork problem or anomaly that prevented people from being routinely admitted. My mother did remember that they had to wait a few days because they were using her uncle Nick Kroeker as their U.S. contact person and had listed his address as Newton, Kansas. But in the time between the original paperwork and their arrival, Nick had been transferred by the railroad company to an office in Chicago, so now their destination was not Newton but Chicago.

One other thing I wonder about is their citizenship status at the time they arrived here. Did their immigration papers list them as stateless (i.e., subjects of the Russian Empire, which no longer existed)? Or were they classified as German citizens? I’ve never run across any indication that my grandfather Hans was classified as a German citizen, which is a little strange since he was born in Hamburg. His father (my great-grandfather Jakob) was apparently considered a Russian citizen during World War I in Germany and had some restrictions of his activities during the war.

In Chicago, Hans started an import-export business. There didn’t seem to be a particular focus – it included all kinds of smaller manufactured items. One of their more active products was a steerable automobile headlight, the Steer-A-Lite.

Hans made use of contacts he had developed in Europe, maybe based partly on contacts via the network of supporters of the Licht im Osten mission and maybe also contacts he had made while working in Berlin. He also used connections with various friends or distant relatives in the Russian Mennonite diaspora; they had a Canadian office in Kitchener, Ontario, for example. Several of Hans’ brothers also went into similar businesses back in Europe, but probably a bit later. The business seems to have gone well for a while.

This picture from Christmas 1929 seems to show some prosperity. But the end was already in sight with the economic collapse of 1929.

This picture from Christmas 1929 seems to show some prosperity. But the end was already in sight with the economic collapse of 1929.This picture from Christmas 1929 seems to show some prosperity. But the end was already in sight with the economic collapse of 1929. I don’t know exactly when the business came to an end. It looks like it struggled until around 1933, but it may have become sort of a sideline before that already, since Hans at some point started working for other larger companies in similar types of export-import work. His knowledge of multiple languages – German, Russian, English – seems to have been his major advantage in work situations.

Hans and Tina had a variety of other international and religious contacts in Chicago. They were in touch with some of the Mennonites in Chicago; my mom talked about “the-Hofers-and-the-Tschetters” (as if that was all one word). They were involved for a while in some kind of Russian evangelical church. My mom and uncle attended a German-language Lutheran grade school for a while. It seems like there were also a good number of contacts with individual Mennonite and Russian immigrants – people who weren’t affiliated with churches or other institutions.

In 1935, my grandfather Hans went to jail in Chicago. From what little I understand of the story, he was working as the manager of an apartment building and was accused of siphoning off rent money to buy liquor. There’s really no good way of knowing whether this was true or whether he was just a convenient scapegoat for someone else’s embezzlement.

In any case, the rest of the family went to Manitoba for nine months while Hans served a jail term. Tina’s three sisters had come to the Elm Creek/Culross area of Manitoba in 1926 so there was a large family group to take care of her and the two children for the time being. Apparently one of her brothers-in-law actually drove down to Chicago to pick them up. So this was yet another border crossing for part of the family.

In 1936, the family moved to Newton. My understanding is that they arrived on Memorial Day, at the beginning of the hottest summer on record for Kansas. My mother had started high school in Chicago. I’m not sure if my uncle had already finished 8th grade there or whether he started that grade here in Newton in the fall.

Hans had a lot of trouble finding any kind of steady work, both because of his personal problems and because of the economy in general. One thing he became especially involved in, which had started already in Chicago, was writing and translation. The most successful piece of this financially was translating materials between German and English for various Mennonite church agencies. But Hans put a lot of effort into writing various pieces for secular magazines and newspapers, both in German and English. He wrote a lot of filler-type items, some nonfiction articles on a variety of topics (some drawn from his import-export business experience), a lot of opinion pieces and some general journalistic types of items.

His success along these lines was limited but better than a total failure. He had some pieces published in places like the Chicago Daily News (a short story) and some European publications like Deutsche Post aus dem Osten. A good number of his writings were published in Mennonite periodicals, both in North and South America, for which he wasn’t paid. A lot of his material was published under pseudonyms for some reason; in this he was like several other of his Russian Mennonite contemporaries such as Dietrich Neufeld/Dedrich Navall.

At some point, Hans came into contact with Gerald Winrod, the Wichita evangelist and right-wing political figure. Winrod had a lot of Mennonite publishing contacts so it’s not surprising they met each other. My grandfather became more or less a ghost writer for Winrod, with a European network and personal experience in early Soviet Russia that were probably an asset for Winrod’s politically oriented publishing work.

Hitler and the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933. Because of his own experiences and the fact that his family lived in Germany, Hans followed events there pretty closely. As with most Russian Mennonites, he strongly sympathized with the anti-communist theme in Nazism. His own interests and his work for Winrod put him into the far-right, anti-communist, Nazi-sympathizing network both in the United States and in Europe. So part of his work for Winrod was to harvest this material for Winrod’s publications and put it together for Winrod’s use.

Much of my grandfather’s writing for Mennonite publications came to focus on politics, defending the new Germany and attacking any hint of favorable attitudes towards the Soviet Union. He became the conduit for an offer by the VDA (National Association for Germans Abroad) to give a large set of books (all obviously politically approved in Germany) to Bethel College, and also a shortwave radio (so students could listen to broadcasts from Germany). Both were turned down.

Hans wasn’t alone among Mennonites in his sympathies for Winrod and Germany. Lots of Kansas Mennonites read Winrod’s publications and voted for him when he ran for office. J.R. Thierstein, the editor of The Mennonite and a Bethel professor, was probably the most well-known German sympathizer among Kansas Mennonites.

The VDA was probably the instigator for my grandfather’s next border crossing. In 1939, he was offered the opportunity to go to Germany along with a large group of other American Germanic opinion leaders (journalists, teachers and pastors, mostly of ethnic German background) for tours and propaganda, to see the new Germany firsthand. I don’t know what all went into the decision to go on this trip; certainly the opportunity to see his parents and siblings was part of it. Part of it also was clearly his own interest and sympathies for the purpose of the trip. Maybe it was a long-shot search for better employment; maybe an escape from conflicted relationships here.

So Hans left for Germany in late summer 1939. Once there, he apparently spent several weeks on the programmed tours with the group, and when that was ended went to his family in Wernigerode. That was around Sept. 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland.

What happened to Hans at this point isn’t entirely clear. Apparently the New Germany turned out to be less attractive up close than it had been from a distance. He seems to have been put off by what he saw on the group tours and possibly also enlightened by in-person conversations with his father who, as an Old Testament lover, was an opponent of Nazi anti-Semitism.

In return for the trip to Germany, the VDA presumably wanted the tour participants to go back to the United States and propagandize for Nazism, with material being fed to them from Germany. My grandfather seems to have refused this bargain, even though he had already been propagandizing along these lines voluntarily before. So the VDA took away his return ticket and other documents. He claims he was even declared a “Deutscher mit Vorbehalt,” someone who was racially German but politically suspect.

One might hypothesize that all this was just post-war self-justification, but what lends it some credence is that Hans never accepted German citizenship, even though he was born in Hamburg (he claimed he had been pressured to accept German citizenship in 1942 but refused), and that he used the anglicized form of his name, “John Kroeker,” during the war, rather than Hans or Johann, even in Nazi government/party administrative documents. In any case, he remained in Germany throughout the war.

I can’t really track down what all my grandfather did during his roughly eight years in Germany. He probably did some work with the Licht im Osten mission and to assist his father. He also seems to have worked for the VDA briefly.

I do know that at some point he became a civilian employee of the SS. At first, he was apparently in the press division, because of his ability with languages. During the war, he had access to English-language newspapers and magazines; presumably he was supposed to report on their contents to his SS employers. Reading Time magazine and U.S. and British newspapers in Germany during the war gave him a much broader perspective on the world than most Germans would have had. Later he went to work for the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle, the Ethnic German Liaison Office, an SS agency that processed ethnic Germans who were being brought back westwards from the Soviet Union. Presumably Hans’ knowledge of Russian, and of Germans in Russia, were the basis for this assignment.

One of the tasks of this agency was to decide who of these people were really German and who were “lesser” people, with dire consequences for those placed low on the list. My grandfather seems to have known, in general terms, what was going on with Jews and others in the Holocaust while it was happening, although I haven’t found anything to indicate he saw such events in person.

The contacts and inside knowledge Hans developed working with the SS came in useful for some people toward the end of the war and after. His sister had married a West Prussian Mennonite, a Bartel, and my grandfather somehow transported her and her children straight across Germany from the northeast to southwest to safety during the last few months of the war in spring 1945.

Hans’ son, my uncle Jake, joined the U.S. Army air forces. He was stationed for a time early on at Alamogordo, New Mexico, and one day his superiors ordered him down to the local courthouse to take his oath of citizenship – he was still officially a German citizen, an enemy alien, in the U.S. military. Presumably they didn’t know he had first cousins and uncles in the German military, first cousins in the Canadian military and possibly more distant relatives in the Soviet military. And that his father was in Germany. And that his sister’s boyfriend was a conscientious objector in Civilian Public Service.

The main part of Jake’s air force career was as the ground crew chief for a B-29, the Ernie Pyle, on the island of Tinian. He fairly often went along on flights and told of being in the plane over Tokyo when the Japanese surrender was signed. His plane’s parking bay was right next to the Enola Gay in mid-1945.

Joining the air force coming from a Mennonite congregation wasn’t necessarily as unusual as it might seem. The vast majority of Jake’s friends at First Mennonite Church in Newton joined the regular military (although some of those specifically asked for noncombatant duties); only a minority were conscientious objectors. So during the war Jake’s sister, my mother, was writing several times a week to her brother in the air force and to her fiancé in Civilian Public Service.

My mother became a citizen Nov. 3, 1943, in Newton. She told of being upset because she didn’t want to promise to “support and defend the Constitution,” being a Mennonite conscientious objector, but apparently a sympathetic presiding judge told her that it didn’t necessarily mean military defense. My grandmother completed the naturalization process Apr. 5, 1945, in Newton.

When the war ended, my grandfather Hans was in Berlin, having survived all the bombing and reportedly having spent time in the hospital after being hit by napalm. He seems to have started collecting Mennonite refugees almost immediately. He commandeered an apartment building (Viktoria-Luise-Platz) and some office equipment like typewriters and started referring to himself as a “provisional representative” of Mennonite Central Committee. He didn’t even know that MCC still existed. But his proactive approach of act first, ask permission later (if at all), probably saved a good number of lives.

This was the background to the famous Peter Dyck story of the Mennonite exodus from Berlin. Once Peter Dyck arrived in Berlin, some months later, the refugees were taken away from my grandfather and he was kind of shoved aside as unworthy (not entirely without reason). The story has since then been told by the winner to highlight the derivative heroism of Peter Dyck and sweep under the rug the roles of several others, such as Robert Kreider.3 According to some stories, it was my grandfather who convinced the Soviet military officials to finally give permission for the refugee train to leave Berlin.

Hans didn’t get to return to the United States at that time. At some point, he was working for an agency called the “German Debt Administration.” He also claimed to have worked in the office of the Spandau prison. He had a lot of contact with the U.S. occupation authorities (and it seems also with the Soviet ones) and it was through them that he first was able to send mail out of Germany after the end of the war. Somehow he managed to persuade U.S. authorities to give him permission to return, something a lot of others in Germany would have wished to do. He must have been a master of spin.

Hans came back to Newton in July 1947 for a few years, but his wartime experiences obviously gave him a lot more material for psychological maladjustment and difficulty fitting back into normal life. Eventually he left and moved to Rhode Island, maybe in the early 1950s; apparently some friends he had made in the U.S. occupation in Berlin lived out there. He died there in 1964. I had thought he had remained stateless from 1919 on, but recently I discovered that he became a U.S. citizen in Newton May 8, 1952.

* * *

As I’ve reflected back on my childhood years in the mid-1960s, I’ve come to recognize that I had certain experiences that differed dramatically from the majority of my generic American friends and acquaintances then. I’m a second-generation immigrant, a child of a foreign-born parent. (According to Wikipedia, 11 percent of the U.S. population in 2009 was made up of second-generation immigrations. I expect the proportion is probably a lot less in Kansas.) Neither of my parents spoke English until they started school. I frequently heard in family settings people speaking non-English languages, or those who spoke English with a noticeable accent. I traveled outside the United States already at age two, which was especially unusual for a blue-collar/pink- collar family like mine. My parents went out of their way to make connections with a good number of immigrants and international visitors in the Newton area, not all of them Mennonites. We regularly received international mail, from Germany, Sweden, Paraguay, Colombia. A couple of times a year, I could see letters with a little red hammer and sickle stamp to my grandmother from her childhood friend and relative in the Soviet Union. This was during the Cold War; it must have been incredibly rare for Newton, Kansas.

It was also interesting, in a potentially uncomfortable way, to bring an exhibit about citizenship into a Mennonite setting. Mennonites, at least in this part of the country, know something about immigration, but themes of citizenship, patriotism, nationalism and militarism raise long-standing points of tension among Mennonites and between them and their non-Mennonite neighbors. There are plenty of opportunities to offend a lot of people across the political and theological spectrum.

The exhibit made me uncomfortable in a number of ways. I found myself trying to simultaneously belong to categories that are in significant tension with each other. An unspoken message of the exhibit seemed to be a pushback against the contemporary popular bigotry against immigrants: “Immigrants are not strange insidious threats, they are potential Americans, they are us.” I can say yes to that.

Immigration is a living memory in my family. By that I mean that people alive today knew the immigrant generation personally. If you go to a Mennonite retirement center in the Plains states, you will find many people who remember their immigrant grandparents of the late 19th century. (In contrast, if you go to a Mennonite retirement center in, say, Indiana or Pennsylvania, you will find very few people who have that personal connection to the immigrant generation; for them immigration is much more of an abstraction.) In my extended family, immigration will continue to be a living memory for some time into the future, as those who are teenagers now remember their immigrant grandparents who arrived at Ellis Island as children in 1926.

But the exhibit celebrated U.S. citizenship as a personal transformation, almost a conversion experience, a step from darkness to light. I don’t find myself saying yes to that. My personal experiences, family stories, my social network, my sense of the first person plural, doesn’t match the boundaries of citizenship very much at all. There isn’t darkness out there and light here. I often have more in common, and more important things in common, with people who aren’t Americans than I do with generic Americans.

The popular equation of patriotism with militarism remains a point of tension for some Mennonites, including me. The current citizenship oath goes like this:

I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law; and that I take this obligation freely without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God.

Oddly enough, this text isn’t established by Congressional legislation. It’s in 8 CFR 337, the Code of Federal Regulations. So there’s some flexibility: you might be allowed to affirm instead of swear an oath, you might be allowed to leave out the phrase “so help me God” or to leave out the clauses about military service.

Nevertheless, the oath makes the explicit connection between citizenship and militarism. Should citizenship in one country imply an automatic readiness to kill citizens of others? Would you recite this statement in order to be an American by choice? This is usually followed by the pledge of allegiance, which some Mennonites won’t recite. Should we say the pledge of allegiance together?

On the other hand, my personal experiences and family stories also make links in the other direction. (I’m writing here more from my Kroeker perspective than from my Thiesen side.) It’s simply a fact that the United States and Canada offered my family and many other people a place to belong, a place of freedom and safety, that they were unable to find elsewhere. And this continues to be the case, as current immigrants show us. The series of flags makes that clear in a symbolic way.

The United States has represented political values to the world in a way that most other countries have not. It’s uncomfortable to say this knowing that the United States (and Canada) usually failed to live up to its values (Native American dispossession, slavery, racial segregation, etc.) and that even when my family members were being admitted, others (Jews, for example) were being turned away. America is not the light of the world, but maybe it has sometimes been a light – a dim one – when there were few lights around.

And the connection between patriotism and militarism looks different when you’re standing as a pallbearer in a cemetery, listening to the young men in uniform play “Taps” and watching them go through the ritual of folding up the flag and presenting it to the family.

I hope I’ve given you some material for further reflection.

Anatomy of a Mennonite Miracle: The Berlin Rescue of 30-31 January 1947,Journal of Mennonite Studies 9 (1991): 11-33.