Note on this photo the original design for the Ad Building in the background

Note on this photo the original design for the Ad Building in the background

What’s a Thresher? Recovering Bethel College’s Symbolic History

Previous versions of this presentation were given as a Bethel College faculty seminar, Nov. 26, 2007; a Bethel College convocation, Apr. 25, 2008; and a Kauffman Museum Sunday-Afternoon-at-the-Museum talk, Jan. 6, 2013.

Behold, I will make thee a new sharp threshing instrument having teeth: thou shalt thresh the mountains, and beat them small, and shalt make the hills as chaff— Isaiah 41:15 (KJV).

Over the past few years, since about 2007, the threshing stone has moved to much greater prominence in Bethel imagery than before. I think I’m one of the people responsible, sort of accidentally, because I tried to answer the question of when and why Bethel athletic teams came to be called Threshers. This is a Bethel tradition — one of several — that was forgotten during and after the 1960s.

To thresh

means, as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it, to separate by any mechanical means, e.g. rubbing, shaking,

trampling, stamping, beating or intermittent pressure, the grains of any cereal from the husks and straw; esp. by beating

with a flail; now (from the latter part of the 18th century) also by the action of revolving mechanism in a mill or machine.

Also, the verb was in early times applied to the trampling and stamping of oxen, or the dragging of heavy rugged things

over grain laid on a smooth surface or

floor.

Thresh

is closely related to the word thrash

and, in fact, in the OED the words thresh,

threshing,

etc., appear

under the head word thrash,

which comes from an ancient Indo-European word for making a rattling noise. To thrash, of course,

means to beat completely or thoroughly.

Thus Threshers

is a suitably violent image for an athletic symbol.

Threshers

gestures to a pioneering spirit

and other clichés of an agricultural heritage.

Being Threshers

is distinctive — I don’t know of any other Threshers in college or high school sports. (There is a minor

league baseball team called the Threshers, but they’re named after a variety of shark.) We stand out from all the lions,

tigers, bears, warriors and other worn-out commonplaces of athletic symbolism.

Some of our neighbors, of course, are also distinctive. The Wichita State Shockers, for example, or the Hesston (Kan.) High School Swathers also make use of agricultural references. It’s interesting that these agricultural metaphors are all harvest-related — no plows or seed drills or manure spreaders, but threshers, swathers, shockers. Also, they’re all pre-industrial — no combines or tractors. The Newton High School Railroaders, or Railers as it has been shortened, make a fairly rare industrial connection.

Some symbolism seems to lack the necessary violent spirit: the Hesston College Larks (which reminds me of the Whizzo Chocolate Company), or the Goessel (Kan.) High School Bluebirds or the University of Saint Mary Spires from Leavenworth, Kan.

What about some of the other Mennonite colleges? There are the Tabor College Bluejays (you’ve observed real blue jays —

noisy and intrusive) from Hillsboro, Kan.; the Goshen (Ind.) College Maple Leafs (as it says on their website — not Leaves

),

which seems a little mysterious; the Bluffton (Ohio) University Beavers (their website shows a very mean-looking beaver);

the Eastern Mennonite University Royals (apparently an unimaginative reference to school colors) from Harrisonburg, Va.;

and the Fresno Pacific University Sunbirds (the cliché of sunny California).

Other distinctive or odd symbols nearby would include the ethnic labels of the Bethany College Swedes, Lindsborg, Kan., or the Inman (Kan.) High School Teutons, or the Southwestern College Moundbuilders (where in the world does that come from?), Winfield, Kan. The Clinton (Okla.) Tornadoes seems like tempting fate, doesn’t it? My current favorite is the Pius the Eleventh High School in Milwaukee: the Pius Popes and, of course, the Lady Popes. (The Inquisition ought to investigate them.)

So there’s no shortage of odd symbols; there are even websites devoted to this kind of thing. And speaking of odd — coming back from that digression — you have the Graymaroons. Until spring 1960, Bethel teams, yearbooks, etc., were called the Graymaroons.

Obviously this comes from the school colors, chosen by the senior class in 1907. (1)

April 1907, the

Bethel College Monthly, the regular publication of the college at that time, said, The maroon and the gray have now been definitely adopted as

the College colors and a number of the students will provide themselves with pennants. Why can we not also have a good College

song? Where is our poet?

(2)

Unfortunately, no one recorded anything more about how maroon and gray were chosen. There’s nothing in faculty or board minutes or any further explanation in college publications. Interestingly, the University of Chicago also has used maroon and gray as its colors for many decades. Its athletic teams are known as the Maroons. The colors were chosen at least as early as October 1902.(3) Maybe this was a prompt for the Bethel colors.

The symbolism of the threshing stone actually has a long history at Bethel, back to about the same time as the school colors.

In spring 1903, C. H. Wedel, the first president of Bethel, reportedly set up a threshing stone in his front yard. The

Bethel College Monthly

of June 1903 as a bit bemused in its tone: Professor C. H. Wedel recently acquired an interesting relic in the shape of

an old threshing stone, such as were formerly in general use in Russia … This valuable relic of former agricultural methods

now occupies a prominent place in Professor Wedel’s yard, but there is little danger that anyone will carry it away.

(4)

The stone came from Wedel’s father-in-law Heinrich Richert’s farm. The house and yard where Wedel displayed it sat where the Fine Arts Center is now — the stone might have been sitting on the grassy area just to the east of the FAC. (That house was moved in 1963 to 201 W. 27th, so it still exists.)

Alexander Petzholdt, Reise im westlichen und sudlichen europaischen Russland im Jahre 1855 (Leipzig: Herman Fries, 1864), 157.

Alexander Petzholdt, Reise im westlichen und sudlichen europaischen Russland im Jahre 1855 (Leipzig: Herman Fries, 1864), 157.Threshing stones like this came into use among Mennonites in what was then part of the Russian Empire, today part of Ukraine, in the early 1840s. (5)

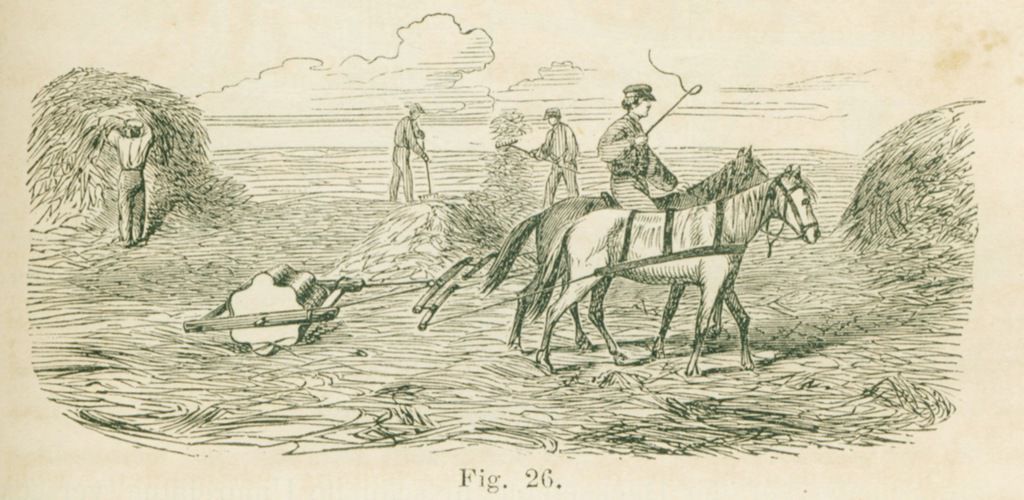

Here is probably the earliest depiction of our kind of threshing stone, in Ukraine in the early 1850s.

I’ve only found two early photos of a threshing stone in use. Unfortunately, there is no identification with the photo. I think it comes from Russia in the 1890s, but I don’t have anything more than that. It’s interesting in that it’s a double hitch of threshing stones.

Here's the other one, also undated but probably 1890s, in Koppental, Russia.:

The stones are all remarkably similar — each with seven teeth, 30 inches wide, an inner radius of 8½ inches (from the center to the base of the teeth), outer radius of 12½ inches (from center to end of teeth). These measurements match from stone to stone to within an inch or less.

These implements were made of limestone, which as you know is calcium carbonate. Limestone is a mineral that originated from various chemical and biological processes in oceanic environments. Kansas is packed full of limestone in various forms laid down in prehistoric oceans that covered this area. On campus here, you see limestone everywhere. The Administration Building is made of it, and most of the other similar light-colored stone you see is limestone.

Much of this building stone, and the threshing stones, were quarried in the Flint Hills, in Marion and Chase counties, where there are still active quarries, like this one just east of Florence.

The limestone in the Flint Hills was laid down in the Permian period, which, as you will remember from your study of geology, was 240-290 million years ago. (6)

Such limestones often include marine fossils and chunks of flint, which you can find upon close examination of the Ad Building, for example.

When Ukrainian Mennonites migrated here in the 1870s, they brought along wooden patterns for reproducing threshing stones. (7)

The Newton Kansan of April 22, 1875, reported rather scornfully:

A car load of Mennonite threshing machines were unloaded at this place last week and conveyed to these farms north. They are manufactured at the rock quarries of Chase county, and consist each, of a large rock about four feet long and two and a half in diameter, drossed [dressed?] the narrowest way in six pointed star shape [got the dimensions and number of teeth wrong]. A rod is placed in the end of each as a pivot, and by which they are drawn over the grain in the manner of a wheel. We learn that these people have already invested $3,000 [that would be over $50,000 in 2006 dollars] in these highly enlightened articles of agricultural machinery, which are not much better than the old manner of treading out grain. —

Threshers,The Newton Kansan, vol. 3, no. 36, April 22, 1875, page 3. (8)

The Kansan editor was right to be somewhat scornful. Threshing stones were already on their way out, replaced by new industrial agricultural machinery — an area in which the Ukrainian Mennonites were some of the major innovators in Europe. So threshing stones were really only used for one generation. As early as 1878, observers reported threshing stones were largely abandoned in favor of new machinery. They had become antiques or mementos (Andenken). (9)

They make pretty unwieldy antiques. Since we know the dimensions of the threshing stone, we can estimate how much one might typically weigh (without having to pick it up and carry it to the bathroom scale). The average radius is 10.5 inches — since they’re symmetrical you don’t have to worry about the teeth, you can just average the inner and outer radius — squared times π, times the length of 30 inches. You can do this all in your head, can’t you? It gives you a volume of about 10,000 cubic inches or about 5 3/4 cubic feet.

Now, limestone varies a lot in density, but if we pick sort of a middling value of about 150 lb. per cubic foot we get a weight of, say, 850-900 pounds. My threshing stone weighs 820 pounds (we did take mine to the scale).

Now that we’ve explored the materiality of the threshing stone, let’s get back to the threshing stone as a linguistic trope — a metonym or metaphor or allegory or anagnorisis or something like that. C.H. Wedel’s dragging a 900-pound memento into his front yard in 1903 was noted, but didn’t really have any impact on the visual symbolism of the college. It wasn’t until a generation later that threshing stones appear in the record again.

On November 16, 1934, the threshing stone was adopted as the official symbol of Bethel College. (10) This was sort of a mysterious decision, like many others. It's not mentioned in faculty or board minutes. There were no news releases.

Presumably it was the decision of Edmund G. Kaufman, one of the most memorable personalities from Bethel’s history. He had become president in 1932 and was energetically and vigorously molding the college.

A brief note in The Bethel Collegian reported on a short ceremony near two threshing stones, one of them the one that had

been in C.H. Wedel’s yard, that had been placed in front of the old Science Hall, on either side of the main door. (11)

Apparently

this was envisioned as a new tradition for the college, an annual freshman initiation ceremony at the threshing stones. The

very limited reporting about the new symbol made explicit reference to the pioneering spirit

and all those clichés. (12)

The 1936 yearbook, the Graymaroon, (there wasn’t a 1935 yearbook published), carried some photos of the event and revolved around the threshing stone visual image.

The yearbook included several threshing stone design elements.

Some stickers were made up to distribute to students. But as you can see, they just didn’t get it — they didn’t understand the potential of the new symbol.

Here’s another variation on the same theme, from the late 1930s.

This is in the BC vertical file under Promotional materials 1930-1939

; dates from ca. 1936-38; has adhesive on the back;

don’t know what it was used for; found with several other promotional items printed at Bethel College press. This has 16

teeth, oddly enough.

Actually the stones must have been placed there before fall 1934, because the title page of the 1934 Graymaroon shows them there already.

For the celebration of the college’s 50th anniversary in 1938, they created a seal which does in fact show a threshing stone if you look closely enough.

The text associated with it referred again to the pioneering spirit

and all that. Also, the 1938-39 college directory,

associated with the 50th anniversary, had a threshing stone image on the cover that seems not to have been used anywhere

else.

The stones in front of the Science Hall were occasionally used as sites for photo ops. This is the 1941 homecoming queen Lois Woodworth from Attica, Kan.

Despite being declared the official symbol, the threshing stone didn’t really gain a secure place in Bethel visual symbolism.

There were occasional usages, such as this 1941 letterhead (which is wrong, with eight teeth) or on yearbooks. This is the

1943

Graymaroon. You see how awkward it looks — it’s because it has only six teeth. It is somewhat similar to another one from roughly

the same time, labeled Bethel College Foundry

and made of cast aluminum.

The foundry version has eight teeth, but it is distorted in a similar way to the 1943 Graymaroon version so that one might think the same person drew both of them.

In the Oct. 1, 1944, Bethel College Bulletin,(13) there was this note:

On Monday evening, Sept. 11 [1944], students gathered in front of the Kauffman Museum for the annual emblem service. A spotlight shone on the Russian threshing stone, the Bethel College emblem. Dr. H.A. Fast read Scriptures and Willis Rich gave an inspiring talk. From the museum, the group went to the athletic field and gathered around a bonfire. Music and some thoughts expressed by Ernst Harder created an atmosphere of fellowship and a desire to be loyal to God, to our fellowmen, and to our calling Christ Jesus.[sic] p. 3.

I have not found any other reference to an annual emblem service,

so we don’t know if this had been going on since 1934,

or whether it continued after 1944. It does indicate that at least one of the stones had been moved from the old Science

Hall to the museum (which was where the Student Center is now).

About this time we get the first hint of what was coming 15 years later. In the Nov. 22, 1945, issue of The Collegian, there

was a short comment titled Threshers? Sure...

This is the earliest use of the word Threshers in this way that I’ve found.

Finally an idea that has been an unrecognized part of the atmosphere and pattern of thought for several years twists itself into the consciousness of this student body. It is as encompassing and dynamic as the threshing stone that represents the colorful and traditional background of Bethel. It fits just as magically and rhythmically into the school spirit and ideals as a sheaf of wheat into the panorama of our rolling prairies. It is the name ‘Threshers’ as a unifying name for the students of Bethel. There is a definite and urgent need for this immediate unity! Soon we will be meeting the Swedes, the Bulldogs, the Vikings and etc. and we’ll need terminology that is more vital and powerful than just ‘Graymaroons.’

It was signed by W. C. & P. G.

The only students I can find with those initials were Wilma Clegg, a sophomore, and

Phyllis Gates, a freshman. But the

Graymaroon

label hung on tenaciously.

This is one of the more elegant yearbook uses from this era, the 1948 Graymaroon.

Along with the homecoming queen, a homecoming parade and floats are also abandoned Bethel customs. A video clip, which may be the earliest Bethel-related video we have, shows the homecoming parade arriving at what is today Fischer Field at Athletic Park in Newton, in 1949.

Note the violent threshing stone image on one of the floats in the video clip below.

Sometimes the threshing stone and Graymaroon

were jarringly juxtaposed.

This is a variation of the same image that goes back at least to 1941, with eight teeth.

Here’s another nice variant — the 1956 commencement invitation stationery.

In the late 1950s, it seems like there was again a certain amount of dissatisfaction with the Graymaroon

concept (or lack

of concept). It seems no one remembered the Thresher idea from 10 years before. In the Nov. 30, 1956, issue of The Collegian,

Ted Zerger, one of the editors, posed a question for student comment: Should Bethel adopt a new athletic symbol? If so,

what would you suggest?

Six student responses were quoted, all from the classes of 1957 to 1959. Only one favored keeping the Graymaroon

symbol.

Two suggested Buffalo or Bison. (Stop and contemplate that for a bit — the Bethel Buffalos,

or the Bethel Bison.

That

has kind of a ring to it.) The other students didn’t have specific suggestions.

Jane Epp said, Somewhere in the student body should be some genius creative enough to design a mascot for dear old B.C.

We definitely need some tangible symbol whether we keep the name of Graymaroons or change the name. But if the name is changed,

why not use some creativity there too, and give our school a name, not necessarily realistic but something no other school

has?

And Kathy Lohrentz said, I would like to be in favor of Bethel adopting a new athletic symbol. No appropriate symbol

comes to my mind, but whatever the new one might be, I would suggest something a bit unique.

Wasn’t Graymaroon

already

unique?

The Dec. 15, 1956, issue of The Collegian carried a brief, unsigned article, Does Team Need Change of Name?

The student

council had opened a contest for the creation of either a Graymaroon symbol or a new symbol. The prize was $20. That would

be around $135 in today’s dollars. (14)

An editorial in the Jan. 11, 1957, issue endorsed the idea of a name change. Here it said that the Letter Club had initiated a campaign to change the symbol.

The March 15, 1957, issue a few weeks later added a threshing stone to the masthead, without any other comment. The threshing stone masthead continued in some form for the next 30 years.

We don’t really know anything more about this flurry of interest in change. It may be that the image below was one of the

proposals. Note the 57

in the center:

The June 1957 issue of the Bethel College Bulletin, intended for the constituency rather than students, featured the threshing stone prominently, without making a connection to athletic symbolism.

The threshing stone symbolized these clichés:

Note that the drawing has eight teeth, not seven.

Nothing seems to have come of the movement for change in 1957. But there was some foreshadowing.

The March 1959

Bethel College Bulletin

had this drawing on the front, with a brief note describing the introduction of a new Bethel College Awards System

and

asking people to suggest a name for it.

The 1959 yearbook carried a threshing stone photo on an interior page, although it didn’t fit in with the overall design otherwise.

1959 began a period of presidential transition at Bethel. David C. Wedel had been president since 1952, following on the 20-year presidency of Edmund G. Kaufman. It seems that there was a somewhat negative mood at Bethel at the end of D.C. Wedel’s presidency, a sense of malaise or stagnation, with students talking a lot about academic mediocrity.

Following Wedel’s resignation, the board appointed J. Winfield Fretz as interim president.

Here he is less dignified, in a sort of faculty follies skit called The Hair-Raising Adventure of Choosing an Acting President

for Bethel College,

Feb. 26, 1960.

Another of the prominent personalities of Bethel’s history. Fretz had taught at Bethel since 1942. He was from eastern Pennsylvania originally and thus was an outsider to Bethel’s local Kansas constituency. He was active in sports in high school and looked back on that experience fondly. He was a sociologist, as were many other Mennonite academics from that time period (such as E.G. Kaufman).

Just before his appointment as interim president, he had spent the academic year in Paraguay on a research project. He returned to find himself appointed interim. I suspect it might have been partly because he was absent during the preceding school year and thus maybe less tangled up in whatever irritations the college community was feeling at the time.

In addition to his college teaching, Fretz ran a restaurant in Newton called The Guest House and was involved in anti-segregation efforts in the ’50s. His restaurant was the only one in Newton in the mid-1950s that served customers of all races equally.

Fretz was a vigorous, energetic personality and didn’t view his interim position just as a placeholder, waiting for the new long-term president to arrive. He jumped into the position with vision.

One area to which he turned attention was athletics. Within the Athletic Department, according to one source, there was some continuing undercurrent of wanting to change team names. Maybe this was still simmering from the 1957 discussion.

The department already had a fairly long tradition of an annual Buffalo Barbecue

and so the name Buffalo

was at the

top of the list. George Buhr, the basketball coach and later athletic director, reportedly had some practice shirts made

up with the name Buffalo — the Bethel Buffalos. That supposedly got some negative attention from Fretz, who thought Buffalo

seemed to suggest slow and lumbering.

(15)

But then he was from Pennsylvania...

Fretz gave an opening school address

on Sept. 12, 1959, called The Recovery of a Cause,

advocating the need for regaining

a sense of institutional cause or vision. (16)

He also organized a study group of faculty, administrators, and board members who were reading the book The Idea of a College

during the 1959-60 school year. (17)

The Quaker theologian

Trueblood argued that a college needed to focus on an idea.

In his search for fresh vision and administrative ideas for the college, Fretz turned to the Association of American Colleges (today the Association of American Colleges and Universities), (19) the national organization for liberal arts colleges.

This organization had begun an administrative consultant service, whereby an outside consultant would be available to visit a college and bring a different set of experiences into contact with the institution. Fretz requested a consultant for Bethel. The person assigned was Thomas E. Jones, a sort of Quaker counterpart to Bethel’s E.G. Kaufman. Like Kaufman, Jones had been a missionary in the Far East, in Japan, and then a college president, of Earlham, a Quaker school (he also served as president of Fisk University). (20)

Jones came to Bethel during March 1960. He was here for the Folk Festival,

a predecessor to today’s Fall Festival. So

he would have seen various demonstrations of pioneer living and historical activities.

This was the poster for the 1960 Folk Festival, showing a threshing stone outline. Another Folk Festival print item — maybe a placemat? — with Low German sayings on it, from about the same time —undated but possibly also 1960 — uses the threshing stone image again.

Jones’ response to his visit seems quite enthusiastic. He wrote a report of Impressions and Suggestions

for Bethel. Reading

the report nearly 50 years later, one finds his tone rather glib and some of his impressions just plain wrong. For example,

he says that there is little or no architectural design on the campus.

This despite the fact that the Ad Building was designed

by the rising architectural stars of the 1880s, Proudfoot and Bird, who went on to found one of the most prominent architectural

firms in the Midwest in the first half of the 20th century. (Their successor firm, under a different name, still exists in

Des Moines.)

Jones also seemed quite optimistic about building positive relationships with the Newton community. Unfortunately, 1960 was only about 15 years after the very tense relationships of the World War II era, and just at the beginning of the even worse town-gown relationships of the Vietnam War era.

But our main interest is in another element of Jones’ report. He followed Fretz’s lead in talking about a Bethel idea

and offered a concrete symbol for it.

Fortunately, Bethel has a distinctive symbol which could be used to typify these values and make them relevant not only to its own heritage and constituency, but to the larger Kansas community and the world. This is the ‘threshing-stone’ in the shape of a roller whose ridges, when rolled over the wheat, separate the live kernels from the useless chaff and straw. Having experienced this type of threshing when heavy stones in the form of prejudice, incarceration, and torture were again and again rolled over them, the Mennonites can reveal afresh the life-giving power that is within them. Once more in the face of secularism, irresponsibility, crowd-mindedness and authoritarian control, the imperishable qualities of life and light in the Mennonite faith and practice can be made apparent and compelling to society as a whole.

It sounds very fifties-ish, Cold War-ish doesn’t it?

Jones had such a good time at Bethel that he was invited back a few weeks later as the 1960 commencement speaker. Fretz said in a letter back to the Association of American Colleges right after Jones’ visit:

From the time the Joneses landed on the campus until the moment they left, they had something significant to contribute. I think they set on fire our total college community in a way that has not been duplicated in the eighteen years of my association with the college. One of the remarkable things was the way they were able to quickly size up the situation and see golden opportunities where many of us seemingly were too close to notice them. (21)

But the important follow-up to Jones’ visit, as far as our questions about Bethelsymbolism are concerned, came just a few

days later in a chapel talk, March 21, 1960, by Winfield Fretz titled This Stone Shall Be a Witness.

We don’t have a full

text or recording of his talk, but his detailed outlines allow us to reconstruct it pretty well.

His title and the first part of his talk were a routine rhetorical gesture at the Bible. The title comes from Joshua 24:27

and he commented about how stones are mentioned 40 times in the Bible, along with a comment about references to threshing.

(One of those verses, by the way, was Habakkuk 3:12. You have that one memorized, don’t you? In the old King James Version,

it reads Thou didst march through the land in indignation, thou didst thresh the heathen in anger.

Maybe that would make

a good motto for Thresher athletic teams. The modern translations aren’t as interesting.)

Fretz continued, All great causes need symbols; all colleges need them. Bethel College needs a symbol that fires the imagination,

that calls forth loyalties and stirs the soul.

Fretz argued that the threshing stone:

stands for something significant; suggest a process — something dynamic;

originality . . . There are thousands of wildcats, panthers, bears, lions; hundreds of bulldogs, braves. These are symbols of the caveman, the savage, the uncivilized;

suggests the ideals of industry . . . a symbol of motion, power, firmness;

a graymaroon is hard to picture; (22)

Fretz didn’t seem to be aware that the threshing stone had been declared an official symbol back in 1934. He concluded his talk with, again, a rhetorical gesture to the Bible, reading Joshua 24:25-28.

This chapel talk seems to be

it

— this is apparently the point at which the Graymaroons vanished into the mists of abstraction and the Threshers began.

But the implementation of this change is still a mystery. There don’t seem to be any memos or detailed instructions saying

Stop saying ‘Graymaroon.’ Start saying ‘Thresher.’

There’s nothing in the faculty or board minutes, nothing in the faculty-staff

bulletin, nothing in the daily announcements, nothing in the

Bethel College Bulletin, nothing in The Collegian. But the switch was immediate and universal.

The word ‘Graymaroon’ vanished from the vocabulary and memory of the Bethel community.

This energetic interim president changed Bethel’s corporate culture drastically, in a way that, at the time, he probably thought of as a minor public relations housekeeping matter.

It would be interesting to speculate about how Bethel’s experience of the 1960s might have been different if Fretz had stayed on. What would it have looked like with this energetic and optimistic leader, someone who already had experience confronting the town and business community of Newton over difficult political issues in desegregation? Instead, he went on in 1963 to be the founding president of another Mennonite college, Conrad Grebel in Waterloo, Ontario.

After the spring of 1960, of course, the threshing stone had a more secure and frequent place in Bethel’s iconography, although not a constant one. There was a flurry of usages in the early ’60s.

On your right you will find a photo from the April 4, 1960, Buffalo Barbecue. That’s Dick Harp, basketball coach from the University of Kansas, speaking. See the threshing stone on the pennant in the background. Presumably they were already using these — I don’t think they had had them made just in the couple of weeks before this banquet.

In May 1960, the first Thresher Awards were presented, based on the academic award system proposed back in March 1959. (23)

The fall 1960 football program prominently featured the new label Threshers.

The Collegian started using a new threshing stone design on its masthead on Oct 14, 1960, replacing the one from 1957. This is the same as the one used in the 1940s and 1950s — the 1953 athletic letterhead for example. This one is still wrong — it has eight teeth. (The 1957 Collegian version had seven.)

The November 1960 Bethel College Bulletin used this logo, which continued through May 1966, also a continuation of the 1940s version.

The actual threshing stones themselves, once in front of the old Science Hall, continued to get moved around, in a way we aren’t able to trace completely. In the early ’60s, for example, one of them was in front of what was then the Kauffman Museum, located about where the bookstore is now.

Here’s the 1962 homecoming poster — another different use of the threshing stone image, not really matched by or modeled on any other one. Here’s one of the more fascinating uses of the threshing stone image.

This is the front of a brochure used for fund-raising for the Fine Arts Center. Inside, it explicitly references the threshing stone.

You can see that we have the usual clichés: pioneer spirit and all that. Then on a further page....

We see that the Fine Arts Center is a threshing stone!

And here’s our lovely building as built:

This campus planning presentation drawing from the early 1960s shows another interesting case. We see the Fine Arts Center, and a few other speculative buildings. The one with eight lobes is particularly interesting, maybe another threshing stone reference. I wish they had built it.

Here are a couple more homecoming images — a 1963 float and another very quaint and yet violent one, also 1963

Note that this one has the wrong number of teeth on the threshing stone — that’s why it looks odd.

In summer 1964, some new Bethel signs were put up along Main Street, a gift of the 1964 senior class. The sign includes another version of the threshing stone that doesn’t seem to have been used elsewhere.

Here’s a 1964 homecoming float, in front of what is now the Mennonite Library and Archives building, the old side of the

library, using a threshing stone as a bizarre bowling ball: Bethel strikes again.

(The homecoming opponent in 1964 was

the Kansas Wesleyan Coyotes, so why the goofy-bird bowling pins? Maybe the 1964 date on this slide is wrong.)

The 1960 yearbook, which was probably already in production when Fretz made the switch, was still labeled Graymaroon but it was the last one. Besides the title, it took a while for yearbook graphic design to catch up. The 1964 Thresher yearbook cover used a small threshing stone image; the rest of the cover is pretty subtle — can you see the blue square-spiral against the black background?

The 1965 Thresher yearbook used the threshing stone on its title page, but not on the cover.

In another interesting homecoming image, probably fall 1966, you see the pennant, the shirt and the banner on the car. I don’t know what the symbol inside the threshing stone is, or why the blue color, or who the people are.

1966 homecoming. This is from III.1.A.35.b folder 140; on the back it says Russell Hiebert, Bethel College, SH Club float

in homecoming parade mid-1960s, photo by Daniel Gaeddert

; photo was printed in Apr. 1967 so it’s probably fall 1966; threshing

This is from III.1.A.35.b folder 140; on the back it says Russell Hiebert, Bethel College, SH Club float in homecoming

parade mid-1960s, photo by Daniel Gaeddert

; photo was printed in Apr. 1967 so it’s probably fall 1966; threshing stone on

car, on shirt, on banner; Goering Hall in background.

Here’s a pen and ink drawing by Bob Regier from 1966, maybe a study for a logo. Quite similar to the 1938 directory image. Or maybe it’s not by Bob Regier. I found it in a folder along with a memo to him about the logo in 1966, but he doesn’t remember drawing this.

In the September 1966 Bethel College Bulletin, we see a new, very abstract threshing stone logo.

I didn’t even recognize it until I saw this December 1966 Bulletin cover, which shows the intended reference to the threshing

stone — a stack of books — and the letter forms BC.

This one is also by Bob Regier.

Bob recalled that in 1966 he produced two design options for Bethel president Vernon Neufeld for a new Bethel College mark.

One was this one. The other was a highly stylized threshing stone, which will appear below. The threshing stone was thought

to be too provincial

so they went with this BC symbol, which continued in use in the

Bethel College Bulletin

until the end of 1994 (maybe a few years more on letterhead). (24)

The threshing stone theme came back to a string of yearbook covers. Here’s 1966 and 1967.

The title page spread inside the 1967 had a big image of the threshing stone, and a very sixties-looking 1968.

In fall 1971, The Collegian adopted the threshing stone symbol in the form it had appeared on the cover of the 1968 yearbook

Who is Gower Champion anyway? And here’s the 1971 yearbook cover.

Notice it again has the wrong number of teeth.

Now we jump ahead a bit. Here’s a glimpse of the physical location of one of our threshing stones in May 1977, close to the early-’60s location. This is probably the one that’s now in front of the Ad Building. I would guess that it was moved from there in preparation for construction of the Student Center, probably less than two years after this photo was taken. Also note that the sign has a threshing stone on it..

In fall 1977, The Collegian adopted yet another form of the symbol.

This is the other image designed by Bob Regier in 1966. I think it was used pretty extensively in college publications in the late ’70s, sometimes reversed so the hitch angles to the left instead of right as in this version. The Collegian used this version through the spring of 1987.

Here’s another one from Bob Regier. He didn’t remember exactly for whom this was done, but it was likely from the early

1970s. It wasn’t widely used — I’ve only seen it in the sample that Bob gave me. It may be the first use of an anthropomorphic

thresher person. It sort of has a Grim Reaper

reference, with the farmer carrying a scythe and looking grim. How about

the Thresher of Death

?

Here’s another incarnation of the stone, on a 1982 receipt.

There seems to have been a long gap in use of the threshing stone image in yearbooks after 1971. But the 1983 book, designed by Scott Jost, made extensive use of it — one of the more systematic examples of its use.

And several places in the interior of the book;

also note the quotations.

It appears that all of these 1983 stones erroneously have six teeth instead of the needed seven — a major flaw in what otherwise is one of the most extensive threshing stone usages in yearbooks.

Here’s another new site for a threshing stone. Some of the college food service contractors in the 1990s gave out plastic mugs. This one is from Pioneer Food Service in about 1999. (This version of the image appeared on the 1982 receipt we saw earlier.) In about 2000, another adaptation of the threshing stone appears. Again, you wonder why it took so long for people to think of this.

And above is the pep band, called the Threshing Machine,

wearing them at the Sept. 22, 2001, football game. (25)

Jared Gingerich is said to be the creator of the foam Stoney

idea and name.

Reportedly, the next instantiation was inspired by the foam Stoney.

Both photos scanned from the Oct. 3, 2001, Collegian.

This Stoney

was designed in four views by Jess Rempel for Marla Krell in the Career Center in 2006, and named by Jose

Valenzuela. (I do think there was an earlier version floating around, a stick figure with a threshing stone head, but I haven’t

been able to find any examples of it.)

The most recent official

instantiation of the threshing stone is by Ken Hiebert, what is now called the legacy symbol.

It appears on the 2001 yearbook, below, the first time in almost 20 years that the symbol was used on the yearbook. This

version seems kind of dangerous — a half-ton block of limestone whirling through space.

Actually there’s another Ken Hiebert version, this little one inside the BC fetus symbol — it looks like the brain, with

the spinal cord running down from it. Maybe there’s an evolutionary biology lesson here: Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.

The brain/threshing stone is a Permian oceanic fossil, which develops into the brain of Bethel College. This photo is from

March 2007. The sign was replaced later in 2007 with this similar version:

Here the threshing stone is the stomach, with the digestive tract trailing behind it.

And the legacy symbol

variants continue to appear on college publications (above), such as when the periodical formerly

known as the

Bethel College Bulletin

became Context in 2002. (I suggested at the time that they not give the new publication a name, but just use the symbol

as the title, but they opted for the more conventionally atmospheric Context.)

Or in the 2007 Masterworks choral program, above — the threshing stone as May flowers. What kind of April showers created those?

On Sept. 10, 2009, The Collegian brought back the threshing stone to its masthead, using the legacy symbol, after more than 20 years’ absence. Here’s the most recent variation of the Ken Hiebert legacy symbol, in the 125th anniversary logo introduced in fall 2008. It also now appears on the college signs on Main Street in North Newton.

Burning threshing stone sparks thrown off by anniversary fireworks. Maybe somebody could build us a threshing stone-themed pyrotechnic display?

Our kind of threshing stone — a seven-toothed rolling cylinder of limestone — is a uniquely Mennonite artifact; unique, actually, to a specific Mennonite subset, the Ukrainian Low German Mennonites of the 19th-century Russian Empire. It’s surprising to me that any physical artifact could be unique to such a small cultural group. The entrepreneurial energy that created Bethel College all came out of that particular Mennonite experience, so the threshing stone is a deeply embedded symbol for Bethel.

Over the last few decades, we have often used the ringing of our famous bell for ceremonial occasions. This dates back to Vietnam Moratorium Day, Oct. 15, 1969, when Bethel appeared on national TV with the tolling of the bell. But the bell has little long-term association with Bethel. It came from Meadows Mennonite Church out in Mingo, Kan., and those conservative people were likely appalled at its use for political protest. The bell came to its prominence accidentally, as students pulled it out of the museum on a whim as a prop for the moratorium. Since then, of course, it has been used many times and has acquired a certain aura.

Now we have revived an older symbol, more integrated into our longer history. Starting in about 2007, apparently at Dale Schrag’s instigation, the threshing stone has become more of the focus for college ceremonial occasions.

John Thiesen is archivist at the Mennonite Library and Archives and co-director of libraries at Bethel College in North Newton, Kan. His Jan. 6, 2013, presentation of this material complemented the special exhibit Threshing Stone: Mennonite Artifact & Icon,

created by Kauffman Museum at Bethel College and on display there Oct. 6, 2012-Jan. 20, 2013.

Threshers,The Newton Kansan, vol. 3, no. 36, April 22, 1875, page 3.

Bethel Adopts New Emblem,The Bethel Collegian, vol. 14, no. 10, Nov. 21, 1934. This waspage 4 of the Evening Kansan-Republican, vol. 50, no. 150, same date.

Story of Our New Emblem,Bethel College Bulletin, March 1935, page 16.

The Inflation Calculator.

Bethel College chapel talks.