Small Steps Cover

Small Steps Cover

Review: Water From Another Time; Small Steps Toward the Missing Peace; and Leading and Following: The Path of Service

Water From Another Time: Today’s Questions, Yesterday’s Wisdom. Morgantown, PA: Masthof Press, 2010.

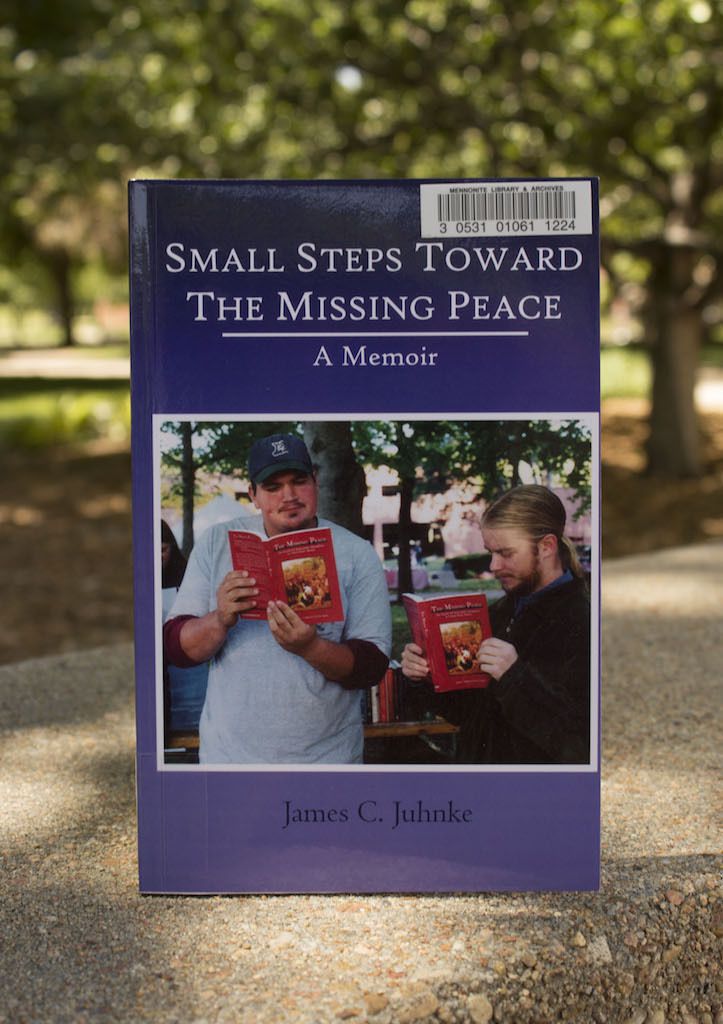

Juhnke, James C. Small Steps Toward the Missing Peace: A Memoir. Flying Camel Productions, 2011.

Nikkel, Larry W. Leading and Following: The Path of Service. Hillsboro, KS: Print Source Direct, 2012.

As a book lover who cherishes the physical act of holding a paperback, the aesthetics of a bookstore, and the satisfaction of flipping pages with my fingertips, there is muchto lament in the seismic changes taking place in the publishing industry. Amazon, that behemoth of booksellers; e-books like Kindle and Nook; the cheap-and-easy access to online reading material: every sign points to the inevitable demise of the physical book’s place in our cultural landscape.

In at least one way, however, changes in the publishing industry should be seen as not only a boon for historians and scholars, but also for lovers of story and for those who have any kind of story to tell. It might be argued the burgeoning industry of print-on-demand has democratized publishing, allowing more writers to get their product into the hands of readers without having to work with big publishing houses, agents, editors, and distributors.

Print-on-demand allows independent book houses and self-publishing companies toprocess small runs of books, removing overhead costs and saving publishers the economic losses associated with a poor-selling product (and writers the angst of storing boxes full of unsold books). Although this means anyone with a little bit of money and a finished—or even partially finished—manuscript can publish, it also means people whose ideas or lives might be of interest to a niche audience will more likely see their work to print.

As a result of print-on-demand businesses, a number of Mennonites have, in recent years, been able to publish their memoirs—life stories that certainly matter to co-denominationalists, family members, and others interested in the Mennonite story, but that will matter less to those not situated in their target audiences. This trend in publishing should thus be especially promising for Mennonite scholars, as the memoirs provide insight into faith and praxis as experienced by Mennonites living in a specific place and time.

In the case of the memoirs reviewed here, that place is the United States in the mid- and late 20th century, a time when many Mennonite groups were undergoing enormous changes of their own. Writing about their lives as Mennonite academics, scholars, and leaders, the men who have chosen to narrate their individual experience were also reflecting larger movements within the church, from agrarian to urban centers, and from insular communities to a more active engagement with the world around them: with politics and government, with public organizations, and with people living far beyond the borders of North America.

As a historian, James Juhnke is no doubt well aware of these larger trends affecting 20th century Mennonites, and indeed, his 2011 memoir, Small Steps Toward the Missing Peace, though focused primarily on his own life experiences, yet shows as well the ways Mennonites were being transformed by the culture around them. Printed by Flying Camel Publications in 2011, Juhnke’s memoir is an interesting read because of the author’s close attention to world events that helped shape his life narrative and that solidified his commitment to peace. Juhnke served as a history professor at Bethel College in North Newton, Kan., from 1966-2002, with several breaks during his tenure to run a political campaign, serve in Africa with Mennonite Central Committee, and to teach English in China. His first wife, Anna Kreider Juhnke, whom he met in 1961 at a peace conference, also became a professor at Bethel College, teaching English; she passed away in 2005, and Juhnke subsequently married Miriam Nofsinger several years later.

Clearly, Bethel serves as an important backdrop to Juhnke’s life experiences, first as a student and then as a faculty member. In some ways, Juhnke’s personal narrative is also the story of Bethel College and North Newton, a Mennonite enclave buffeted by forces, including citizens of next-door Newton, who sometimes challenged Mennonites’ core values. Perhaps no chapter in Juhnke’s memoir reflects this better than Political Campaign, 1970,

in which Juhnke details his unsuccessful run for congress on the Democratic ticket, and the polarized climate he faced.

Reading about Juhnke’s brush with a political campaign over forty years later, one must conclude that not much has evolved in U.S politics. Communities still remain divided over some of the issues Juhnke mentions: the U.S. military’s role in other countries; the need for pacific voices in our government; the place of patriotism in political campaigns; and whether a candidate could possibly do anything to change the tide of unemployment and a sour economy.

That Juhnke based his campaign on a nonviolent message while the Vietnam War raged was not for political expediency. His commitment to pacifism has been life-long, and thus, a desire to be a peacemaker becomes the central theme holding his memoir together. He traces this commitment through his early work with MCC-Pax, his Ph.D. research, his time in Botswana, and his later work at Bethel. While much of Juhnke’s scholarship has focused on denominational history, it has also been deeply rooted in the Mennonites’ peace testimony, and the ways that testimony has often been challenged by a government and civic culture that could not comprehend the power of nonviolence.

And then, of course, a pacific metaphor drives Juhnke’s memoir title much as it does the memoir itself, which alludes to a book Juhnke published in 2001, The Missing Peace: The Search for Nonviolent Alternatives in United States History. Co-authored with Carol Hunter, then a professor at Earlham College, the book views United States history through the lens of peacemaking, an alternative lens for viewing history,

Juhnke writes, showing how given events—from the Native American encounter down to the Cold War—moved people toward reconciliation and justice or away from that goal

Juhnke seems to suggest through this shaping metaphor of small steps

that his life’s trajectory has been toward this project, certainly, but also toward understanding his own life, Mennonites, and the scope of U.S. history through the perspective of peacemaking. At his memoir’s end, Juhnke writes that The Missing Peace was his contribution toward a more peaceable world, but it’s clear from his memoir that the small steps

he took along the way have also progressed the cause of peace.

Seen this way, Small Steps Toward the Missing Peace documents not only Juhnke’s life, but bears witness as well to the important work peacemakers still need to do. Although some readers might wish for more personal reflection—for more insight into Juhnke’s family life, for example, or into his own spiritual journey—this type of mediation is clearly not the heart of his memoir. Instead, because Juhnke focuses his life story on his peace work, readers who are likewise committed to peacemaking will be inspired by Juhnke’s efforts, and will hopefully feel the call to continue taking steps toward the missing peace.

Those wanting a more personal autobiography may turn instead to Larry W. Nikkel’s Leading and Following: The Path of Service, published by Print Source Direct in 2012. Both Juhnke and Nikkel come from families deeply rooted in the Mennonite faith, heralding from small Midwest towns; both spent parts of their vocations at Mennonite colleges a stone’s throw from each other. Yet Nikkel’s denominational tradition is with the Mennonite Brethren, and although he served as president of Tabor College for almost a decade, he was not an academic in the traditional sense, spending most of his career in the public sector as an administrator first at Prairie View (a mental health system in Newton, Kan.), and then with Mennonite Health Services, a network of mental health service organization that allowed Nikkel to work from a home office in Hesston.

Many chapters in Nikkel’s autobiography address the challenges of working within these mental health organizations, as well as the satisfaction Nikkel experienced during his career. Readers unfamiliar with these organizations or with their personnel may find these sections of Leading and Following less interesting, if only because Nikkel provides significant details about his work life, including his travels and his colleagues.

Still, it is evident that during his time with these mental health organizations, Nikkel worked with many extraordinary people, fellow servants who remained committed to their vocations not because of their compensation (which, as with most jobs in the field and with Mennonite organization, was not significant), but because they felt called to the organization and to its clients. The title of Nikkel’s text reflects a theme that has clearly guided his vocation and especially, it would seem, his decision to leave Mennonite Health Services and become president of Tabor College without having any substantive experience working within higher education. Nikkel had attended Tabor, worked on some of its capital campaigns, and served on its board, but unlike other college presidents—who often spend their lives moving up the ranks within academia—Nikkel arrived at Tabor, first as interim president and then as its president, from the outside. Nonetheless, the memoir makes it clear that Nikkel felt called to this role of leadership, and that his accepting the presidency was an act of obedience, as had been the other weighty life decisions he made.

Perhaps because I am also in higher education, and because I grew up only blocks from Tabor College, I found the chapters on Nikkel’s Tabor leadership to be the most compelling of the book. Other readers who have similar interest in the inner workings of a Mennonite college will also find interest in what Nikkel has written about his time there. From his reflections, it is clear Nikkel served the Tabor community well, carrying them through a difficult time that included falling enrollments, budgetary problems, and an athletic program struggling to remain viable. The book’s final chapters address the end of Nikkel’s tenure as president, which nearly coincided with a heart attack he experienced vacationing in Hawaii. While Nikkel describes some of his successes at Tabor (including the building of a new athletic field and townhouses for students), as well as his failures (including conflicts with faculty over salaries), in the end it is a song, written by a student, which reflects best the impact he made at the school, where he was the favorite president

with the best handshake

257. In essence, the song—which Nikkel reprints in its entirety—sums up Nikkel’s time at Tabor, allowing us to see ways his influence extended far beyond capital campaigns and faculty skirmishes.

Although Leading and Following is predominantly focused on Nikkel’s Christian service, these moments when Nikkel turns to his personal life are by far the strongest parts of his book. In the opening chapters, Nikkel details his familial roots, tracing his heritage back several generations to his ancestors’ immigration from Russia to the United States. While the minutia of Nikkel’s family tree might seem of interest only to those who inhabit its branches, this is not the case. Although Nikkel claims, almost apologetically, that the individuals and families who lived pietistic, conformist, traditional lives blend in with all others, offering little of interest to us,

the narrative he tells counters this claim: for in the singular story of Nikkel’s family, we are able to see the particulars of the immigrant experience, a real value in the autobiography he’s written. As Nikkel traces his ancestral lines back to Russia, and then progresses forward to Oklahoma and Kansas, we get a good sense of the difficulties facing many Mennonites traveling from Russia during this era: the long boat rides, illnesses and early death, and the hard work needed to set down new roots in an unfamiliar land.

For Nikkel’s immediate family, that land blossomed into a home on the Oklahoma prairie, and home itself becomes another recurring theme in Nikkel’s story. Early chapters detail his growing up years in Corn, Okla., and his memories there are distinct and often humorous, despite the pain of losing his mother to cancer at a relatively young age. Later chapters return to the idea of home and family, elements Nikkel values as the touchstone for his life, so that he describes in detail the homes he inhabited, and the relationships he develop within their walls: relationships with his wife and children, certainly, but also with friends, with visitors, with Tabor students and faculty. One other aspect of Nikkel’s autobiography worth mentioning is its humor. While parts of the book might appeal more to those interested in mental health, or parts to those interested in higher education, or parts to those who know the Nikkels personally, what pulls these audiences together is Nikkel’s narrative voice, which is conversational, relational, and at many turns, funny. Nikkel relates a number of stories from his childhood, and then his working life, that show his sense of humor and his willingness to laugh at his mistakes. It is at these moments, when Nikkel puts on a more private rather than public personal, that he best reaches his audience.

Still, of the three memoirs reviewed here, Berry Friesen’s Water from Another Time dwells most often on the writer’s interior life, rather than shaping a life story around public presence, as Juhnke and Nikkel do. This could be in part because Friesen’s public presence has been far different than Juhnke and Nikkel; while the latter two men carved their identities through their positions at Mennonite colleges, Friesen has worked as a practitioner, spending time in Minnesota as a lawyer and in Pennsylvania as an Mennonite Central Committee administrator and an executive for several non-profits. Additionally, though, Friesen’s memoir is structured far differently than the traditional memoir, and does not rely on the chronological trajectory that generally drives autobiographies forward. Instead, Friesen chooses to order his life’s experiences around five separate queries: Where will we live? How will we make a living? With whom will we join? When will we dissent? What story will we live by? This alternative structure is compelling, as it allows Friesen to both tell his own life’s story, but also that of his family, of his ancestors, of his community, and of Anabaptists more broadly. In doing so, he shows how our common narratives help shape our understanding of our journeys, as well as how the earlier experiences of others, shared through story, can prepare us to face the road ahead,

and can help us to live as bravely in our times as they did in theirs

181.

Thus, for example, rather than detailing his many vocational opportunities, Friesen explores the broader notion of work in a chapter title How will we make a living?

He begins by narrating his parents’ occupational choices, as reluctant farmers who enjoyed other endeavors—his mother, reading books; his father, selling Fords at a Mountain Lake, Minn. Dealership—more than toiling on the land. Friesen wonders at their seeming ambivalence about farming, noting that his heritage includes 250 years of farmers, although I see many of the men made a living through a mix of activities pursued consecutively or at the same time

78. From there, Friesen examines his familial heritage of farming, but also the broader Anabaptist impulse to work the land, using the draining of the Vistula Delta in 16th-century Poland as a thematic thread tying early Anabaptists and his own family together.

Friesen’s discourse on work continues as he narrates his wife’s connection to farming, as well as consideration of the vocational choice most highly regarded by churches: that is, serving as an international missionary. Although some of Friesen’s relatives assumed this path, it was not to be for Friesen or his siblings, all of whom chose neither farming or missionary work, but turned to education—and then Friesen, to administration—to discover their vocations. Friesen narrates his own occupational journey, from working as a teacher in Iowa, to becoming a lawyer in Minnesota, to accepting an executive position with MCC in Pennsylvania, to having several administrative positions with social advocacy groups in Pittsburgh. It’s clear from the chapter that Friesen has had a rich work history, and that—as Juhnke and Nikkel also express—each job represented a calling to which Friesen faithfully responded.

Finally, Friesen pulls back the lens to consider the idea of work generally, and the ways working for a living might shape broader political realities,

including contemporary cultural conditions: Americans working in jobs they hate in order to consume more cheaply-produced goods

; the shrinking number of artisans and small farmers; the passage of NAFTA and other legislative efforts 98. Friesen sees his own work history—and that of his forebears—as an important reminder that a rich life involves far more than a paycheck, and that what we do every day for a living shapes us

98. The chapter ends with a poem exploring vocation and the challenges Friesen personally faces as someone unemployed and edging nearer to retirement.

Each chapter in Friesen’s memoir follows similar form, allowing the author to explore his own life experiences, but within several broader contexts. Although this might seem disorienting or disjointed, Water from Another Time has a strong sense of unity, as Friesen pulls his seemingly disparate material together under a singular idea: that the experiences of our ancestors have much to tell us about how to live, and that our own lives need to be informed by the deeply rooted values of community, faith, and family. In many ways, the unusual structure of Friesen’s memoir is refreshing, as is his use of several different discourse modes, including poetry, narrative, and lengthy quotes from other writers’ journals, letters, and newspaper accounts.

Still, part of Friesen’s memoir is disquieting, and I would be remiss as a reviewer if I did not mention the unsettling fourth and fifth chapters, both of which mention 9/11 and Friesen’s belief that the U.S. government was at least complicit in the terrorist attacks that occurred on that day, if not integrally involved. Although Friesen has some important things to say in these chapters on dissent and on the stories that shape us, his sense that the U.S. participated in the terrorist assault that killed over 3,000 Americans is difficult to accept, and diminishes for me what was, up to that point, a pleasurable reading experience. While I agree with Friesen that the U.S. government has vastly overstepped its authority by invading Afghanistan and Iraq; while I agree that its saber rattling against Iran is disturbing; and while I agree that our country is far too inured to the dangers of gratuitous violence, I am far less certain that our government’s role in 9/11 deserves urgent discussion at Mennonite assemblies, as Friesen asserts. Mennonites do indeed need to be a dissenting church

and need to challenge the impulse of U.S. empire building, but I fear Friesen loses some credibility when writing about a theory that has been reasonably debunked by a number of prominent historians.

Despite this confounding assertion, there remains much in Water from Another Time to recommend. Fundamentally, Friesen provides an interesting narrative about his heritage, and the ways principles like work, faith, and community shaped him and his ancestors—and, by extension, shape us, his readers. For in writing about his individual experience, Friesen allows others to step inside and understand the Anabaptist experience as it played out through history in Europe and in Russia; and how it plays out now, in North America. This is one of the significant powers of life writing: the opportunity to use one’s own life as an emblem for how others might have lived—or, how they might continue to live.

Therefore, although Friesen’s interest in 9/11 conspiracy might distract from the narrative he tells, I also believe he has every right to convey the story he wishes. Similarly, James Juhnke has the license to write more about his public than his private life; and Larry Nikkel, the prerogative to provide more detail about his occupational endeavors than some readers might find useful. We should probably acknowledge that, were these men writing for a traditional publishing house, these aspects of their memoirs might have been edited or elided altogether from their texts. But because they’ve chosen a print-on-demand approach to publication, we get to see these writers’ lives exactly as they want us to see them, without the mediation of editors, agents and marketers who might demand changes diluting the stories these men want to tell.

This collection of memoirs serves as an important reminder, then, that though the publishing industry is going through seismic changes, there might be reason enough to hang on for the ride. Otherwise, we may miss the opportunity to read significant narratives—about people of faith, answering the call to serve their communities, their denominations, their God.