Does This Church Make Me Look Fat

Does This Church Make Me Look Fat

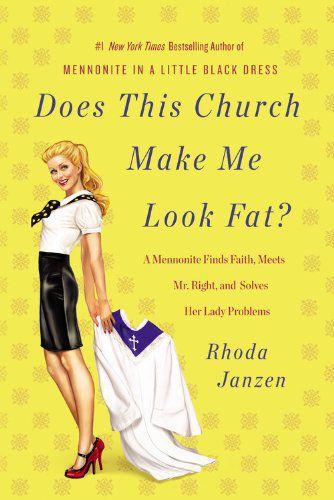

Review: Does This Church Make Me Look Fat? A Mennonite Finds Faith, Meets Mr. Right, and Solves Her Lady Problems

Like many of her readers who identify as Mennonite in one way or another, I have mixed feelings about the work of Rhoda Janzen. When her first memoir, Mennonite in a Little Black Dress, came out, I could not sit in my office with the door open at my secular state university without someone dropping by to tell me about this zesty-looking new Mennonite memoir or to ask me what I thought about it. I felt the way I always feel when a Mennonite makes it big: reflexively proud, as though I am somehow party to their celebrity, and then annoyed and self-righteous, the way people from marginal groups tend to feel when they are represented to the public by another community member. Mennonites are ragingly guilty of this. We have arsenals of sanitizing language designed to negate stories that come from the wrong kinds of Mennonites. We eat our own like champions, particularly if they are women writers, and particularly if they have anything to say that makes Mennonites look less than heroic. I, like many others, found it irritating that Janzen's first memoir conflates Mennonites and Mennonite Brethren and makes the entire lot of us sound ethnically homogenous and allergic to all modern fashion. On the other hand, it seems precious for Mennonites to get too worked up over being poorly represented in a popular book. It isn't the kind of media misrepresentation that is going to kill us, and that right there makes us luckier than a lot of people in the world.

In Does This Church Make Me Look Fat?, Janzen is several years past the end of Mennonite in a Little Black Dress, dating a born-again Christian contractor named Mitch. He is an unlikely Mr. Right for a college professor of Mennonite origin, but as Janzen writes, Advanced education doesn't make one wise. In fact—stay with me here—what if having a PhD makes you a tomfool?

She wears her intellectual pedigree lightly, and Mitch has the wisdom of hard living on his side. After years spent as a drug dealer, alcoholic, and general thug, he finds Jesus and cleans up his act. In describing his personal appearance and demeanor, Janzen draws lavishly on well-worn tropes of working class masculinity; by the end of the first chapter, my head full of images of shaved head and scary biceps,

a huge goateed rocker,

and chest like a scenic vista,

I was imagining someone who looked like a cross between the Hulk and the meth-dealing protagonist on the television show Breaking Bad. His uncomplicated piety is Janzen's primary foil for her own windy faith journey, but she also writes him as a sort of rough-and-ready sex object. (Mitch believed in premarital abstinence, but apparently his pants disagreed.

)

It must be said that Janzen is authentically hilarious. She is no sham as a popular memoirist; she writes dialogue with a comedian's timing that dances productively on the edge of being too glib. Those who tired of Mennonites being the butts of that humor in her first book may find her second to be less offensive. Arguably the worst jibe she gives Mennonites here is the suggestion that their worship might profit from an organized Drag Queen Day. (How and if you find that offensive probably depends on your politics; as a big drag fan, I suspect it may be God's own truth.) By contrast, Mitch's Pentecostal congregation sways, sings repetitive music that lacks narrative momentum, makes unorganized noise, and, not to put too fine a point on it, does things that from an outsider's perspective are easy to mock.

But these are the people with whom Janzen now makes her spiritual home, and when she writes of them humorously, it is gently and without mean-spiritedness. At least it seems that way to me, although not being Pentecostal, I may be missing something.

The contrast to the Mennonite faith of her youth is most stark in Janzen's first Pentecostal healing service,

in which church elders attempt to discern the health needs of their congregation and then write them down on an enormous Power Point screen for prayerful attention. An elder now beckoned the microphone. He looked as if he was getting something, too. 'I'm feeling to say that there's someone here with lady problems!'

While a skeptical reader might quibble that naming an ailment category this broad is a fairly safe bet in front of a room that presumably contains a number of women, from Janzen's perspective lady problems

is prophetic. Days later she is diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer that has already metastasized to her lymph nodes.

Janzen's breast cancer drops rather abruptly in and out of the narrative, but that isn't necessarily a structural flaw in the book. This is not a memoir about enduring or surviving cancer; it's a memoir about cancer as a catalyst for religious transformation, and for romance as well. Mitch proves his mettle to her as a partner when cancer enters the picture. Though Janzen tries to give him a graceful out from their relatively short relationship, he instantly refuses: This is my choice, sugar. I'm the right man for this...You watch and see what the Lord's gonna do.

They proceed together into surgery, chemotherapy, and scary survival statistics, all while planning a wedding. In the spiritual space they come to inhabit as a couple, imminent death doesn't matter nearly as much as you'd think it would. As a reader, this was the point where I had to let go of the incredulity and accept that the experience Janzen relates is too far from my own for me to comment on its believability or its meaning. I absorbed it; I'm still interpreting it for myself. And to do so isn't a bad thing for a memoir to ask of its readers. It helps that Janzen's meandering accounts of living through cancer treatment are some of the most entertaining in the book, aided by the appearance of her sister Hannah and her ever-chipper mother, who as far as I'm concerned is a towering comic character of Mennonite literature.

Despite her grim prognosis, Janzen recovers from cancer shortly before marrying Mitch, and for no discernable reason whatsoever. She admirably refrains from attributing her startling remission to anything in particular, though a decidedly non-Mennonite Holy Spirit makes an appearance at several memorable instances in the trajectory of her illness. Perhaps one measure of a good writer is how well she can pull off writing about her religious faith without alienating readers who don't share her particular variety of devotion. I admit I am a tough customer when it comes to Christian writing, and a tougher customer still when cutely gendered phrases like Does This Church Make Me Look Fat?

are part of the equation. Janzen's religious writing certainly kept me engaged, but not without some wariness.

I tried to read Janzen's faith-fueled resignation over the sexism of her chosen church without leaping to judgment—not everyone has to fight these battles, and if anyone deserves a pass in the struggle against patriarchy, it's someone dealing with life-altering illness. Still, something about her principled refusal of critique sets my teeth on edge. Maybe it's the political season, or maybe it's my own Mennonite baggage, but I take little pleasure in reading an intelligent woman's attempts to trivialize her own resistance to religious patriarchy. Who knew what I would see when I stopped looking for structural and semantic flaws in the organization of this church, indeed of all churches?

Janzen writes. I'm not sure, but I do know from experience that when women spiritualize the practice of humility in a patriarchal setting, we're primed and ready to see exactly what powerful men want us to see.

On a related note, Does This Church Make Me Look Fat? is peppered with superficial references to Janzen's identity as an egghead intellectual,

but it's never quite clear what that means to her, beyond a propensity for attending artsy functions

and diagramming sentences from late Henry James. It's not that I object to academics being humorously stereotyped—heaven knows we deserve it—but given that a conflict between intellectual inquiry and faithful surrender seems to be at the heart of her narrative, I long to understand with greater depth how she negotiates that conflict. I do see that life-threatening illness changes one's perspective on what is important, and Janzen documents that transformation with beauty and grace. But it is one thing to trade balsamic reductions for green bean casserole at your potlucks, and another thing entirely for a devoutly Christian college professor to publicly pit the life of the spirit

against the life of the mind.

The closest that Janzen comes to a fruitful dialectic of mind and spirit is the chapter entitled Up From the Deep,

in which she documents her fumbling through a community devoted to biblical literalism. As a lifelong reader of allegory, Janzen is socially flummoxed when people answer her inquiries about their beliefs with statements such as, We do believe that a big fish swallowed Jonah whole.

To her credit, Janzen isn't flip about what is at stake—particularly in the context of her marriage to a man who believes in hell and plain speech and dislikes what he calls roundabout poetic language.

This could be occasion for reductive statements about surrender and the spiritual limits of critical thought, but Janzen reaches deeper, towards an illuminating meditation on the fragility of meaning in the language we used to describe our religiosity (or lack thereof). Are literal and metaphorical interpretations really so diametrically opposed? Are we as thoughtful as we should be about the meanings of these labels? I should never have asked if my friends believed in a literal fish. I should have asked what the story meant to them,

she writes of the Jonah incident. Now that, in my own teacherly estimation, is the right question to ask.