A video of this presentation can be viewed by clicking here and scrolling down.

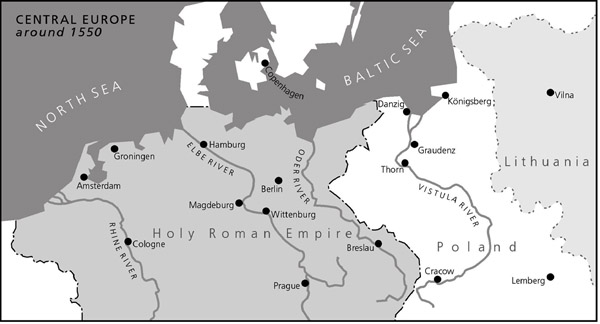

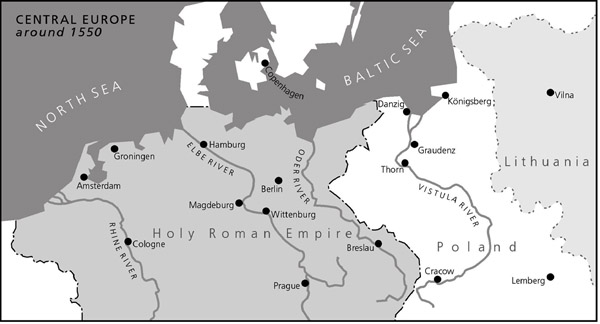

In the 18th century, society in central Europe was legally constituted much differently than it is at the beginning of the 21st century. Two changes in particular in the intervening centuries were of immense importance to Mennonites, namely ideas related to establishing human equality and increasing the centralized power of the state. The initial lack of equality in legal relations left Mennonites vulnerable to persecution, discrimination and exploitation. As long as inequality was perceived as an important foundation of an orderly society, questions of dealing with social injustice in a church setting, unlike today, simply never arose. Given Mennonites' tenuous legal status, the rise of equality seemed to have some obvious advantages on the one hand for Mennonites. The lack of strongly centralized states on the other hand left many opportunities for Mennonites and other minorities to negotiate good terms from local officials for creating settlements even in states where they were technically illegal or to obtain better conditions than the central government intended, thus circumventing the limitations imposed by inequality. The first shift in social relations in the eighteenth century, the strengthening of a central state still committed to an unequal social structure, had obvious potential to be detrimental to Mennonites.

Although a few writers and intellectuals were arguing for equality in the 18th century as part of the Enlightenment movement, the reality for the vast majority of Europeans was one where legal inequalities pervaded every aspect of life. At the highest level in the Holy Roman Empire, for example, only a handful of electors voted for the Emperor who then held office for life. Locally in rural areas, the local landlord was the main legal authority, serving or appointing both judge and law enforcement personnel who were, granted, very few in number. Who one could marry, seldom outside of one's own community and status in any case, where one could live, how one could earn a living, who could brew beer, gather firewood, hunt deer or pick which church to go to on Sunday were all determined by law and tradition and rarely a matter of choice for individuals. Nonetheless, particular individual decisions depended much on the lowest level of local authority since little was standardized given the limits of communication and the miniscule government budgets of the time.

A notorious example of early discriminatory law against Anabaptists was the Imperial Law passed by the Diet or parliament of the Holy Roman Empire meeting at Speyer on April 23, 1529. The text stated:

Although the common law forbids upon penalty of death to baptize again an already baptized person and the emperor at the beginning of 1528 has given a new warning against the transgressors of the prohibition, that sect is still increasing. Therefore the regulation is ordered again, that each and every rebaptizer and rebaptized person, man or woman, of an accountable age shall be brought from natural life to death with fire, sword, or the like according to the circumstances of the persons without previous inquisition of spiritual judges. Against the preachers and leaders of the sect as well as those who persisted in the same or fell back into it no mercy shall be exercised but the threatened penalty shall be ruthlessly performed. Those who confess their error, recant, and beg for mercy may be pardoned. Whoever does not have his children baptized shall be considered an Anabaptist. No pardoned person shall be permitted to emigrate, so that the authorities can see to it that he does not backslide. No prince shall receive the subjects of another who have escaped. This mandate shall in all points be most strictly performed by all in order to perform the duties and oaths to the emperor and empire and to avoid the serious displeasure and punishment of the emperor.1

This criminalization of adult baptism played a role in making the label of Mennonite more popular, as defendants could claim in court or to government officials that the law did not cover them, since it referred to Anabaptists and not Mennonites. The other obvious loophole the law's authors obviously worried about was the willingness of local officials who operated with autonomy actually to enforce the penalties. Indeed, local officials in the Netherlands, in rebellion against the Emperor by the late 16th century, granted Mennonites toleration.

In the 17th century, many local lords ignored this law and tolerated Mennonites (for example, in the Palatine region of Germany), signing contracts that allowed Mennonites to settle and worship yet carefully limiting their religious and economic activities in other ways.

|

The Polish Commonwealth in the 18th century was even less centralized than the Holy Roman Empire. Like the empire, its leader, the king, was elected, but here every member of the nobility was eligible to vote, making perhaps as much as 10 percent of the male population eligible. Since voting was open and not secret, and done in assembly, in reality a small number of the wealthiest nobles had disproportionate influence on the outcome and thus often felt free to ignore the king's decrees. Mennonites settled wherever they could find local landlords willing to sign leases with them. The fact that many came from the Netherlands and knew how to reclaim swampland by building and maintaining dikes made them desirable tenants in the delta region of the Vistula River and along its lowlands further upstream, the original settlements that later fed into the Grace Hill congregation.

Mennonites had an unusual relationship with the kings of Poland. Much of the delta land where they settled had been conquered by Poland from the Teutonic Knights in a series of wars that ended in 1466. Land that had belonged to the knights was now assigned to the crown of Poland and used to finance the royal court. Mennonites were given leases here and up the river by royal administrators and their rent money was used to pay for court expenses by whoever was king. The kings in turn issued decrees - known as charters of privileges - that granted Mennonites specific rights, creating in effect a set of laws that applied only to them. This practice fit perfectly with a social structure based on inequality and groups fulfilling different roles. The earliest recorded such charter was signed in 1642 by King Wladyslaw IV, but it referred to similar documents that went back to the 16th century. He noted how Mennonites had been involved in reclaiming swampland and thus, "At the humble request of the aforementioned inhabitants of the Marienburg Delta, we confirm, by virtue of our royal authority, every and all rights, privileges and freedoms granted by the [previous kings], and which were regularly observed by these inhabitants in the past. Nothing is excepted, all rights, freedoms and customs which they have used in the past are approved, retained, and protected by this our present decree. We wish to maintain and affirm them in full force."2 The edict concluded by thanking the Mennonites for the cash payments they had made in the past and promising them exemption from future special taxes, highlighting yet another ambiguous feature of early modern political arrangements. Were these recurring payments, most often made at the start of a king's reign or whenever the state was under financial stress from war, taxes, bribes, fees, gifts or something else yet?

The vague nature of these royal promises left a lot of loopholes open for Mennonites seeking to move to new settlements or make new arrangements but it also made it possible for officials to creatively interpret the documents as well. One of several such examples happened in 1676 at a session of the provincial legislature in Marienburg. A high-ranking administrator from the western end of the territory proposed expelling the Mennonites as a dangerous sect on whose account God undoubtedly punished the area with recurring floods. At first his proposal met with much approval, but the local nobleman in charge of collecting rents on royal lands as well as the local city councils in Danzig and Elbing that had a lot of Mennonite tenants on their lands pointed out the economic advantages of having these people around and the motion was defeated. When the same nobleman made a similar proposal at the national legislature when it convened later in the year, others again spoke up for the Mennonites and accused him of wanting to profit by getting a share of the heretics' land after he had driven them out. The king at that time, Jan Sobieski III, intervened on behalf of the Mennonites.3

Mennonite settlements in Poland were somewhat fluid. The passage of time required new leases as new landlords took over by purchase, inheritance or, in the case of royal lands, by new appointments; new arrangements could not always be concluded satisfactorily. Sometimes local political quarrels affected Mennonite settlements or population growth might mean that new and affordable lands needed to be sought out. So although life was relatively stable for most individuals, over time Mennonites created new settlements throughout the 18th century with some regularity.

Mennonite theological understandings of the state supported, perhaps even drove, this peripatetic lifestyle. Mennonites conceived of the state as an instrument ordained by God to punish evildoers and reward the good, but as something outside God's central focus for relating to humanity. A 1755 confession of faith in use in the Vistula River region stated it this way:

We confess that God, who rules over everything, has instituted political authorities for the protection of the good and the punishment of the wicked and that no one may resist it but rather everyone must show it all loyalty, respect and obedience in order not to oppose God's Word. At the same we prefer not to occupy any political office in the belief that we should avoid any part of revenge (Matthew 5:38-39) and everything that works against Christian nonresistance and humility. We willing pay taxes to support the state and feel obligated to pray earnestly for it.4

The church as the vanguard of the kingdom of God - of God's rule over humanity - was the main focus of Mennonite interest. The state was a foreign, if necessary, entity whose affairs were of no concern to Mennonites. One expression of this attitude was Mennonite refusal to participate in warfare or to hold most public offices; another was the expressed willingness to move to live under more tolerant political bodies if necessary. In a confession of faith from 1702 written by a Dutch elder, Herman Schijn, translated into German in 1743 and used in the Vistula River region, this connection is made explicit in the section on war. When asked how Christians should respond if insulted or injured, baptismal candidates were taught to reply, "A Christian who has been insulted must join friendliness to wisdom and then pray fervently to God who has the power to save from one's enemies or to give them better thoughts, or if possible one should attempt to get away from them. If all of these efforts do not help, then following the example of Christ and his apostles, one must endure all things with patience, I Peter 2:21, 23, I Corinthians 4:11-13, and James 5:6."5

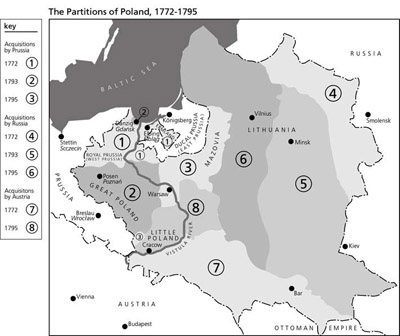

Of the two issues under review here, inequality of society and centralization of government, it was the latter that changed first for Mennonites in the Vistula River region with the partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795.

|

One other major difference between Prussia and Poland was the fact that Prussia had a large, expensive standing army while Poland had virtually no regular army. Prussian officials charged with developing policies for this new territory included a new special tax that would only apply to Mennonites on their list of new initiatives for the king to approve. At the same time, having a new king, Mennonites approached officials with their old Polish charter of privileges and asked that Frederick II grant them the same freedoms as the Polish kings had. To be safe, they added a specific list that included freedom to worship, educate their young, pursue economic activities and be released from military service. To sweeten their request, the Mennonites of the area contributed "two fatten steers, 400 pounds of butter, 20 cheeses, 50 pairs of chickens and 50 pairs of ducks" to the official reception buffet held at the ceremony recognizing the new king.6

The initial response of the Prussian administration was to impose a collective tax on all the Mennonites in the area in exchange for their freedom from military service. The amount was set at 5,000 Reichstaler at a time when 100 Reichstaler was a good annual salary for a skilled workman. This money was used to finance a military high school designed to train local nobles' sons to be officers. The first two years worth of taxes were almost enough to pay for building the school. Once it opened the director was paid 600 a year, the seven instructors got 100 a year plus their room and board. It cost about 3,000 a year for the school to feed the instructors and their 60 students.7

It took until 1780, but Mennonites finally got a new Charter of Privileges from the Prussian king. Although it promised eternal freedom "from military registration and personal military service and their enjoyment of religious freedom and freedom of commerce and livelihood according to the laws and regulations of our Kingdom of Prussia," the reality turned out quite different. The freedom from military service lasted until 1867 but faced serious challenges already as early as 1813, only three decades later.

The promise of economic freedom was already not true when the charter was promulgated. Local officials in 1773 had already started requiring Mennonites to obtain special permits to buy property. Soon those seeking to buy any real estate from non-Mennonites were allowed to do so only if they were buy very small plots or buying property that was in foreclosure. This restriction was linked in part to the fact that the Prussian military tied recruitment indirectly to property ownership by requiring a set number of soldiers from a much larger number of farms. When a Mennonite bought a farm it was removed from the list of eligible farms from which the military could require service, increasing the odds that someone on the remaining farms would be impressed into military service. An additional motivation for the officials might have been a desire themselves to buy land cheaply. Getting rid of Mennonite bidders would help keep prices down.8

At this point, the more centralized nature of the Prussian state really mattered. Mennonites could no longer move to the next county or further up the river to find better lease terms, since this new state they found themselves living in could enforce the same terms of settlement everywhere within the state. Mennonites and all other inhabitants were treated unequally, but the wiggle room was disappearing. Mennonites were soon required to pay special church taxes on top of the tax for military exemption and faced unique restrictions on their ability to acquire real estate. Perhaps getting out of military service made that a good deal nonetheless.

When Prussia got a new king in 1786, Fredrick William II, he and his officials certainly worried this was still too good of a deal for Mennonites. The king issued a Mennonite Edict in 1789 as part of a general review of religious policy that codified the new arrangements on property restrictions and church taxes. Many Mennonites who had been frustrated by their inability to purchase new farms had been trying throughout the 1780s to figure out ways around these property restrictions. Some arranged for non-Mennonites to hold the deed and rent the land back to them at no charge. Some arranged to build a cottage on their new farm for a non-Mennonite family as hired help to live in so the farm would not have to be removed from the military rolls. Some even bought property without registering the purchase but they were evicted. The edict was designed to put an end to all loopholes, the kind Mennonites had been used to creating and exploiting in a less centralized state. Thus it is no surprise the Mennonites in 1788 started to migrate to Russia, where the land was basically free and the military exemption was also free of charge for all non-Russians, one year before the Mennonite Edict was even issued.9

By the end of the 18th century and with the advent of the French Revolution in 1789, the partitions of Poland and the demise of the Holy Roman Empire, loosely organized states in Europe disappeared, unable to compete with the superior militaries of more centrally organized states. Even the Mennonites who moved to Russia for the most part entered into a political arrangement directly controlled by the Russian monarch. Mennonites in the 19th century would have to figure out how to reach accommodations with a single government instead of looking for a safe legal loophole granted by one noble or the other, a crevice in a decentralized and unequal society where it was safe to hide. The Mennonite settlement at Michalin in the Russian section of Poland on the Potocky estates, where Grace Hill forbearers settled beginning in the late 1700s, was an increasingly rare exception of Mennonites avoiding a central government's restrictions with the aid of a single helpful nobleman. If the 18th century saw the end of decentralization, the 19th turned against social inequality as the norm.

1. Hege, Christian, "Diet of Speyer (1529)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 22 June 2011. http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/speyer_diet_of. Emphasis added to highlight how even the method used for capital punishment depended on the status of the people charged.

2. Peter J. Klassen, Mennonites in Early Modern Poland and Prussia (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2009), 199.

3. Horst Penner, Die Ost- und Westpreussischen Mennoniten,Vol. 1. (Weierhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1978), 164-5.

4. Wilhelm Mannhardt Die Wehrfreiheit der altpreußischen Mennoniten Marienburg, 1863), L-LI. This quote is from Article XXI: "Concerning political authority, revenge and the oath" in the 1755 Groninger Confession of Faith reprinted in the appendix and entitled Confession of Faith of the Baptism-Minded, known as the Old Flemish in Groningen Published by Decision of the General Societets Meeting.

5. Ibid., XLV.

6. Heinrich Donner and Johann Donner, Chronik von Heinrich Donner, transcribed by Werner Janzen (Allmersbach, 1996), 24.

7. Mark Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 26-33.

8. Ibid., 35-42.

9. Ibid., 55-59.