A video of this presentation can be viewed by clicking here and scrolling down.

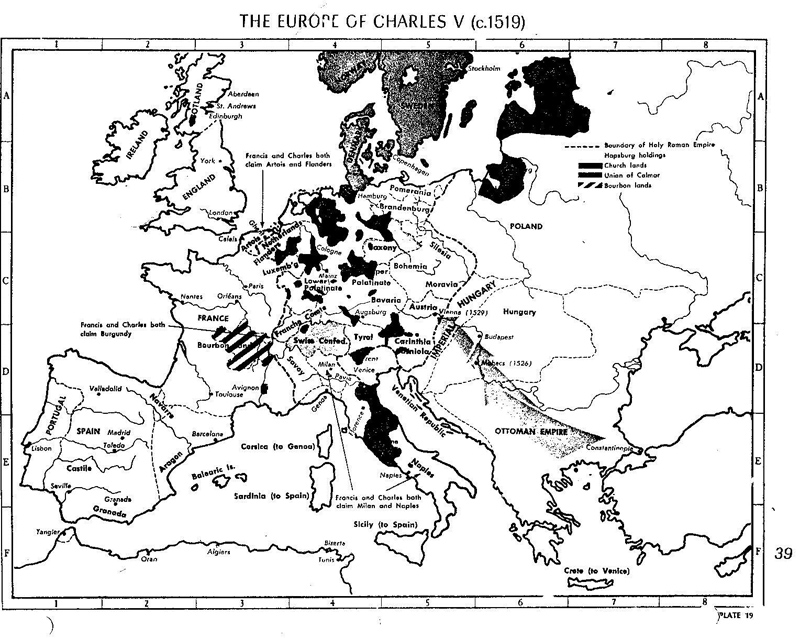

Anabaptism arose in the context of 16th-century Germanic- and Dutch-speaking Europe. The center of Europe - from what is now the Netherlands, Germany and Poland in the north, to Italy in the south - was a loose confederation of city-states and principalities known as the Holy Roman Empire. Some "free imperial cities" had a large measure of self-governance. Some areas under the control of local lords or princes were completely feudal in character and the number of serfs was growing. Other areas were controlled by the Roman Catholic Church - there, the bishop was both secular and spiritual ruler.

In the map below, the black areas represent lands under church control. Many farmers experienced wild economic swings. When harvests were good, crops did not bring good prices. When harvests were poor, farmers could not pay the rent to the landowner lords and went into debt or had to sell themselves into serfdom. The Swiss Confederacy was a de facto independent state, although officially within the Holy Roman Empire, and many Germanic areas of the Holy Roman Empire desired a similar status, with more political and economic protection from the whims of the lords. Only in cities was there anything resembling democracy.

|

In many ways the early 16th century in Europe was a continuation of popular lay piety in the late medieval context. This piety was characterized by:

|

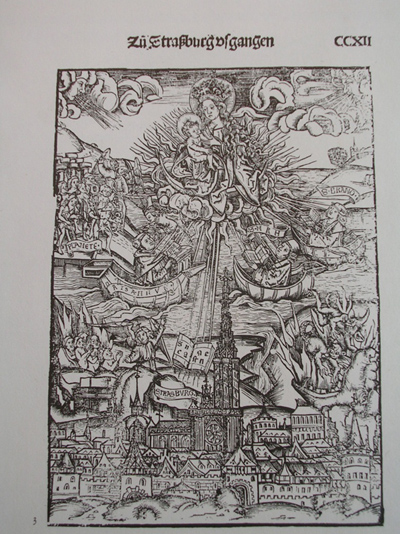

The German Peasants' War of 1525 is somewhat of a misnomer. There was no "Germany" as such in that period of history but rather a large number of German-speaking principalities, cities and fiefdoms within the Holy Roman Empire. Not only peasants but also artisans, merchants and clergy were involved. In fact, clergy wrote some of the manifestos of the "peasants." It did not start out as a war but as a peaceful presentation of demands to the lords. And uprisings occurred not only in 1525 but had started already in the late 1400s and continued in some areas past 1525.

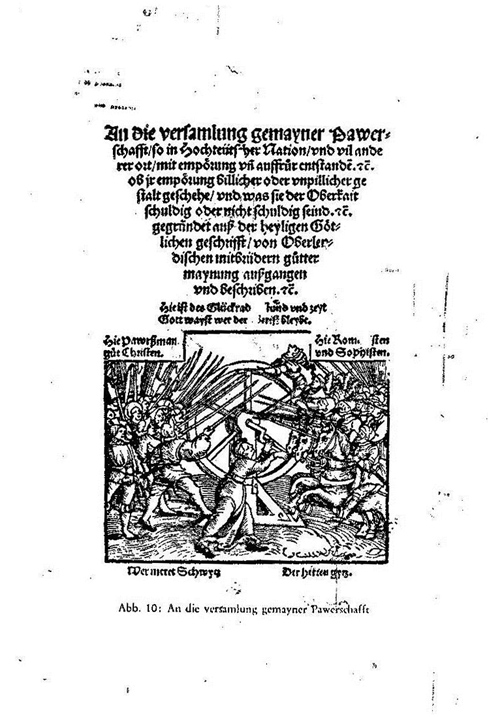

Economic, religious and political issues were interwoven in the demands of the peasants. The Twelve Articles of Memmingen, for example, included not only the right to use common pasture land and forests (which the lords were appropriated for themselves) but also the right for congregations to choose their own pastors. The lords were generally dismissive of such demands, particularly anything that smacked of self-governance. They said, "If we let them choose their own pastors, next thing you know they'll be wanting to choose their own rulers!" Banners carried by the peasants had religious themes (see below) as well as the image of the Bundschuh, the peasant's boot or union boot, which became the symbol of the movement.

|

The lords and their cavalries with their guns attacked the peasants, who were mostly carrying hoes, rakes and other farm implements. The uprisings were put down with massacres. It is estimated that 300,000 people participated in the Peasants' War and 100,000 were killed. Even after the uprisings were put down, lords sought out those who had participated and executed them or had their tongues cut out.

|

The first reported adult baptisms in Swiss Anabaptism were in Zürich in January 1525. Most of the people involved had earlier been in Ulrich Zwingli's Reformed movement: Conrad Grebel, Felix Mantz, Balthasar Hubmaier, Michael Sattler. The issues were:

|

|

|

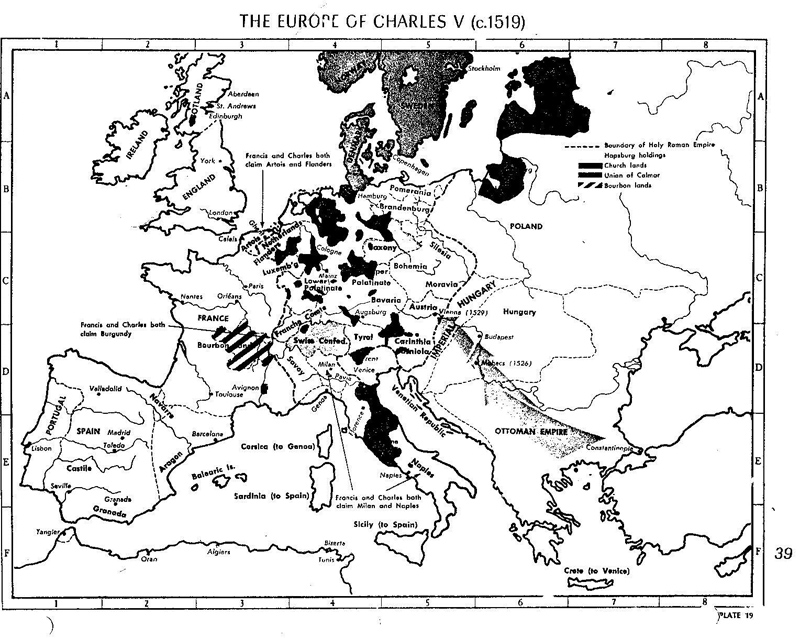

Strasbourg, with an early-16th-century population of about 20,000, was one of the largest cities in the Holy Roman Empire. It had a measure of self-governance as a Free Imperial City. The city council also seemed to have a high tolerance for dissenters. The saying went: Whoever is executed elsewhere will only be whipped in Strasbourg. Already by 1525, there were Anabaptists meeting in Strasbourg, although we have no record of the first baptisms there. Some of the early Reformers, such as Wolfgang Capito, had some Anabaptist sympathies. Because of the relative tolerance in Strasbourg, many additional Anabaptists - refugees from other parts of Europe, particularly the Swiss Confederacy and southern German areas - began pouring into Strasbourg. By 1529-30, Anabaptists may have made up 10 percent of the population.

Tolerance was relative, however. The city council turned down Melchior Hofmann's request for a church building in which Anabaptists could meet. Anabaptists were still subject to arrest and questioning; Melchior Hofmann died in prison; Pilgram Marpeck lost his job as city engineer. But the only Anabaptist executed (for bigamy) had already been excommunicated from his Anabaptist congregation.

Because Anabaptists had come to Strasbourg from many different places, there were at least three distinct groupings of Anabaptists in Strasbourg. The group around Melchior Hofmann shared their mystical visions with each other (one report claimed there were 14 prophets connected with that congregation).

|

|

Elsewhere in southern German and Austrian areas, Anabaptist congregations were also gathering by 1525. Leaders included:

The South German Anabaptist communities were energetic and theologically innovative, but persecution and migration virtually erased these congregations, except for the Hutterites in Moravia.

Before Anabaptism came to the Low Countries, the Sacramentarian movement had gained many adherents. This movement, in spite of its name, espoused a nonsacramental view of the Lord's Supper, which was to be observed as a memorial, not as a sacrifice nor believing the bread and wine to be the actual body and blood of Christ, as the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation insisted. Into this fertile territory came Melchior Hofmann from Strasbourg in 1530. In Emden (now northern Germany), he baptized 300 on his first visit. The Anabaptist movement grew especially in the cities of Amsterdam, Leeuwarden, Antwerp and Groningen, in Friesland and, already in the 16th century, in and around the Hanseatic League city of Danzig (now Gdansk in northern Poland).

Anabaptist leaders and theologians in this area included Bernhard Rothmann, David Joris, Dirk Philips and Menno Simons, a former priest who gathered and organized the Anabaptists in the Low Countries demoralized by the apocalyptic debacle in the city of Münster in 1535. Menno saw the need for Anabaptists to organize into disciplined, nonviolent communities of believers.

Menno wrote that the signs of the true church were:

There was a price on Menno's head, and he and his family were hunted from town to town, but he died a natural death.

|

Many Anabaptists, however, were executed. Why would adult baptism draw such an extreme punishment in the sixteenth century? The mandate of Emperor Charles V in 1529, prescribing the death penalty for "rebaptism," refers to Anabaptists as

Infant baptism symbolized the close interweaving of church and state of medieval Europe. To be baptized was not only to become part of the church but to become a citizen. The Anabaptist separation of church and state was seen by the ruling authorities as treason, withdrawal from the government as well as the Roman Catholic Church. The other main branches of the Reformation - Lutherans and Reformed - kept the bond between church and society. The Anabaptists believed that only those who voluntarily committed themselves to Christ were part of the church.

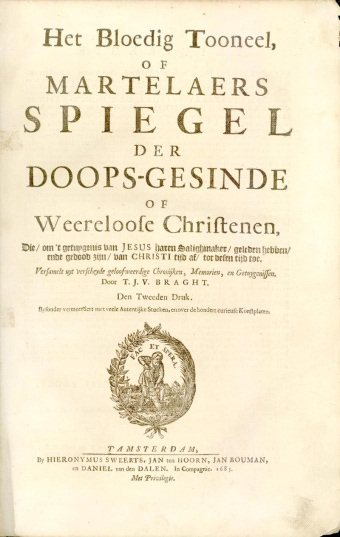

As a result of the authorities connecting Anabaptism with treason and with the Peasants' War, thousands of Anabaptists in the 16th century were burned at the stake, drowned, beheaded or otherwise executed. In the 17th century, Dutch Anabaptist Thielemann van Braght collected the martyr stories into the book we know as Martyr's Mirror. Other than the Bible, it became the most common book in Mennonite households. In its German translation, it was the largest book printed in colonial America.

|

Martyr's Mirror saw the Anabaptist martyrs as part of a long line of martyrs among prophets, apostles, saints and Jesus himself. Thus, the book began with the telling of martyr stories from the early church.

|

The stories of 16th-century martyrs understood martyrdom as taking up the cross of Christ, the proper response of true disciples. Martyrdom was testimony to the truth. Martyrdom was the baptism of blood, as was all kinds of suffering for the sake of the gospel. Most Anabaptists believed in the threefold baptism (water, Spirit, blood). Anabaptists also saw martyrdom as the way peace-loving Christians fight against evil and overcome their enemies. And finally, some martyr stories, particularly stories of women martyrs (about a third of the total), see martyrdom as marriage to Christ.

|

Of course, Anabaptists shared some beliefs with most of Christians of their day. The Apostles' Creed, for example, was simply accepted as necessary to believe. However, it was not sufficient. When the Hutterite leader Peter Riedemann wrote his confession of faith, he started with commenting on each phrase of the Apostles' Creed, then continued with sections on the church and discipleship. In common with Protestants (Lutheran and Reformed), Anabaptists rejected sacramentalism, valued Scripture above tradition, were anti-clerical to some extent and saw God as the initiator and giver of salvation without the mediation of the sacraments or the Roman Catholic penitential system. Anabaptists also shared some emphases with Roman Catholics, particularly the religious orders: the primacy of love in action ("the greatest of these is love") and the belief that the counsels of perfection (in the Sermon on the Mount) were possible to obey. In spite of three distinct geographical areas of Anabaptism in 16th-century Europe, there was a common core of Anabaptist beliefs across groups.

Salvation and discipleship: Anabaptists believed that orthopraxy (right behavior) and orthodoxy (right belief) belonged together. To know Jesus was to follow Jesus, and to follow Jesus was to know Jesus. They saw love as primary, even love of enemies, in contrast to the Lutheran doctrine of "faith alone." Anabaptists embraced the medieval idea of Gelassenheit, putting oneself completely into the hands of God, to be directed by God's will, not one's own. They believed in the possibility of actual transformation by the Holy Spirit, a new birth, not just forensic justification, wherein God declares us justified even if we are still sinning. Anabaptists also believed in free will, that Christians can cooperate with the Holy Spirit's work within them and choose to repent and to turn themselves over to the will of God.

The nature of the church: To the Anabaptists, the church was a spiritual-social-political body, an assembly of believers, a people giving allegiance to God alone, a foretaste of the future city of God. The church was formed by the baptism of those of the age of accountability, a baptism of the Spirit, baptism of water before the gathered congregation, and the baptism of blood, the willingness to suffer or even die for the sake of Christ. The Lord's Supper was both a memorial of Christ's death and a pledge from a good conscience. Members of the church were to practice mutual care and discipling - many Anabaptist congregations had an offering box for the care of the poor among them. They interpreted the whole Bible in harmony with Jesus Christ, as led by the Holy Spirit in the church. They practiced communal decision-making.

Relation to the world: The Anabaptists understood that the whole society was not Christian. Thus, they were to be willing to be different from the dominant culture around them. They were to practice holiness and nonconformity to the evil in the world. They were to be conformed to the image of Christ. And if the society around them was not Christian, then their own context was a mission field. In addition, most Anabaptists refused to participate in the military, to be a magistrate or to swear oaths of allegiance to governments. By the end of the 16th century, this was the standard Anabaptist position on nonviolence.