André Gingerich Stoner is director of holistic witness and interchurch relations for Mennonite Church USA. He was born in Luxembourg, the son of Mennonite mission workers. After attending Mennonite high schools, he received a B.A. from Swarthmore College and earned a Master of Arts in Theological Studies from Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Ind., Indiana. He served for nearly seven years with Mennonite Central Committee in West Germany, 1984-91, first with Church and Peace, an ecumenical peace church network, and then in the Hünsruck relating to U.S. military personnel. Some of those experiences are recounted in an MCC Occasional Paper entitled “Entering Samaria: Peace Ministry Among U.S. Military Personnel in West Germany.” André served as pastor of missions at Kern Road Mennonite Church in South Bend, Ind., until 2010. He and his wife, Cathy Stoner, and their four children live as intentional neighbors with three other households in the Near Northwest neighborhood of South Bend, Ind.

Significant portions of this paper, entitled “GIs in Germany: The Social, Economic, Military and Political History of the American Military Presence, 1945-2000,” were first presented at a conference sponsored by the German Historical Institute, November 2000, Heidelberg, Germany.

The NATO decision to deploy intermediate-range nuclear forces – Pershing and cruise missiles – in Germany and elsewhere in Europe galvanized the German peace movement in the early 1980s. This movement focused attention on the new generation of weapons systems and the military strategies they represented. It sought to mobilize large numbers of German citizens in order to influence German and NATO decision-makers. Very little attention was given to the experiences, interests or choices of the U.S. soldiers who worked with these weapons.

|

Though there were many points of contact between U.S. GIs and German society, stereotypes that U.S. military personnel and German peace activists held of each other were firmly entrenched. Language barriers and a siege mentality in the U.S. military contributed to these perceptions. Confrontational peace movement actions, such as efforts to sabotage maneuvers in the Fulda Gap or blockades of U.S. bases, tended to polarize relations between GIs and the German peace movement. Members of the peace movement lacked direct contact with GIs or knowledge of the history of extensive GI resistance to the Vietnam War. They tended to regard the military as a monolithic block and were generally not interested in engaging in a dialogue with U.S. military personnel.

A notable exception, however, was a small network of expatriate U.S. citizens who developed the Military Counseling Network. In the mid-1980s, Bill Boston moved to Mutlangen, one of several focal points of the German peace movement due to the deployment of U.S. Pershing II nuclear missiles there. In the United States, Boston had been active in a network of Catholic peace workers in New England. In September 1986, he established the Military Counseling Project Mutlangen. He offered an independent source of information about GI rights and discharge possibilities to U.S. military personnel stationed in the Federal Republic of Germany. In the United States, he had attended a course in military counseling offered through the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors in Philadelphia.1

|

Shortly thereafter, Boston began assisting Mark Lane, an 11-year Army veteran who had worked his way up the ranks to staff sergeant. His case generated considerable attention in the media and in the peace movement because he had worked with the fiercely debated Pershing II missiles. He had held positions as a missile crewman, section chief for a count crew, platoon sergeant and training sergeant. Lane began to question his role as a soldier after a conversion experience to the Christian faith. He filed for a conscientious objector discharge on his own, but the Army failed to properly process the claim. With Boston’s assistance, Lane’s claim was processed and he was finally released from the U.S. Army in March of 1987, not as a conscientious objector but for related reasons. Through this case, the Military Counseling Project gained valuable experience and exposure.2

Lane’s story was told in local newspapers and peace movement newsletters. He spoke at several peace movement events in the Stuttgart area. After his discharge, Lane began to offer military counseling to soldiers in the Heilbronn area. For many in the peace movement, it was the first direct contact with a Pershing soldier and helped them think of U.S. GIs as individuals who sometimes struggled with difficult questions regarding their work.

Boston was one of numerous Americans living in Germany who were strongly involved in the peace movement. For several years, 20 to 30 U.S. citizens had been meeting every three to four months to exchange information and to coordinate activities such as letter-writing and petitions. The wide assortment of individuals – from Christian pacifists to adherents of radical splinter political parties – gathered under the name U.S. American Peace Network in Europe (USAPNE). Boston shared his experiences at these meetings and generated interest and support.

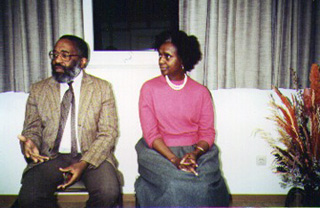

Two other people who frequently attended USAPNE gatherings, Janice Hill and André Gingerich Stoner, joined with Boston to form the Military Counseling Network in the fall of 1987.3 Both Hill and Stoner had received military counselor training through the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors. Hill was residing in Tübingen at the time and Stoner had recently begun a service assignment through Mennonite Central Committee in the Hunsrück, near the deployment site of U.S. cruise missiles.4

MCN adopted the following statement of purpose in November 1987:

Presently more than 250,000 members of the U.S. military and their families and U.S. civilian employees are stationed in the Federal Republic of Germany. Many of them suffer violations of rights and face conflicts of conscience and other difficulties within the military.

The Military Counseling Network advises U.S. soldiers free of charge about their rights under military law and can assist them in achieving various discharges (conscientious objection, medical, hardship, etc). The network of trained civilian counselors was established because soldiers are often poorly informed of their rights and until now had no source of assistance in the FRG outside of the military.

The network also seeks to build bridges and foster dialogue between U.S. soldiers and the German population in order to break down stereotypes and prejudices. MCN counselors are committed to the principles of nonviolence. The network works in close cooperation with European, American and international human rights, peace, church and women’s groups.5

In an effort to broaden the network of qualified military counselors, the fledgling organization sponsored a military counselor’s training, June 1-5, 1988, in the offices of Eirene in Neuwied, in conjunction with the CCCO, a leading advocate for conscientious objectors since WW II with considerable experience in providing counseling to military personnel about their rights and discharge possibilities since the Vietnam War. Based in Philadelphia, CCCO provided staff members Bill Galvin and Lewis Abram, who conducted the training. MCN staff recruited participants and organized local logistics. Twelve individuals participated in the training. Nearly all were U.S. citizens resident in Europe. Now there were trained military counselors in Berlin and Frankfurt as well as Mutlangen, Heilbronn, Tübingen and the Hunsrück, and for a short time in the Hague, Netherlands, and Upper Heyford, England.6

The center of gravity of the organization was in Stuttgart, where Bill Boston worked as national coordinator from the offices of Ohne Rüstung Leben.7 Janice Hill and Boston developed the program of the MCN while other counselors were on call for cases in their area. Boston established a GI info-line for soldiers to gain access to counselors and receive information about military regulations and discharge possibilities.

A 1988 funding proposal articulates the hope that MCN would not only serve military personnel but complement and impact the German peace movement. MCN “see[s] in the soldier not merely the potential killer, but rather the present victim of a militarized society. … MCN provides a ‘missing link’ for the German social change movement by detailing the economic and social factors which drive young men and women to the US Armed Forces. Through its programs MCN established a presence and fosters a dialogue between them. The ultimate goal of such an endeavor is to help individual people, whether in the military or in the peace movement, become capable of waging peace instead of war.”8

To that purpose, Boston served as editor for The Bridge, a newsletter intended to make MCN services known to U.S. soldiers and to be a forum for dialogue between the German peace movement and US military personnel. The first issue, printed in February 1989, introduced The Bridge as “an open forum for dialogue between soldiers and civilians, Germans and Americans, working to promote a deeper understanding of one another and real friendship based on cooperation in confronting the issues of the day.” The newsletter featured articles in both German and English. The first 12-page issue featured the story of a woman soldier stationed in Germany who was filing for a discharge as a conscientious objector and included reports on abuses during basic training, as well as military strategies of low-intensity warfare. Information about MCN and several book reviews rounded out the issue.9

Boston and Hill also initiated Campaign Contact, in which local German peace groups were recruited to distribute The Bridge and other literature from MCN on a regular basis. The campaign was endorsed by Pax Christi and Ohne Rüstung Leben as well as other German peace organizations.10

Hill devoted much of her energy to the Women and the Military project which “address[ed] itself to U.S. women soldiers, military wives, German women and women of other nationalities who have suffered abuse resulting from the U.S. military presence in the FRG.”11 In addition to research and writing articles for The Bridge and peace movement newsletters, the project sought to provide concrete legal and emotional support to women in the military.

The project devoted considerable attention to the case of Dierdre Ellis, a Black woman stationed in Kaiserslautern who was charged with adultery and convicted in a December 1989 trial. While she eventually received a prison term, the man involved was transferred to another location and promoted. MCN’s Women in the Military Project helped secure legal help for Ellis and initiated a letter writing campaign in the United States.12

Organizational and financial instability dogged the Military Counseling Network from the start. While several devoted expatriates served on an advisory board and offered encouragement and assistance and established German and American peace groups like Ohne Rüstung Leben and CCCO provided in-kind services such as meeting space or trainers, it was extremely difficult for MCN to generate financial support for staff time. The June 1989 edition of The Bridge reports that CCCO had officially become a sponsor for the Military Counseling Network. Though CCCO did not pledge any financial support, this made it possible for U.S. citizens to make tax-deductible contributions to MCN through CCCO. The same edition of The Bridge reported that the Evangelische Jugend auf dem Lande (Protestant Rural Youth) was organizing a year-long fund appeal for the Women and the Military project.13 Though some donations were received, it was sufficient only to provide marginal staff support.

Counselors assisted roughly two dozen soldiers in MCN’s first year of existence. Some cases came through direct contacts with soldiers while others were referrals from U.S. groups such as CCCO, Citizen Soldier and the ACLU. Cases included “five conscientious objectors, AWOL, harassment due to sexual preference, racism, sexism, or inability to get along with the command and advice on Article 15s.” The group also assisted a German civilian threatened with losing his work on the basis of his sexual preference.14

The work of André Gingerich Stoner in the Hunsrück, a rural region between the Rhine and Mosel rivers, initially had quite a different character from that of the other MCN counselors. Stoner had come to Germany in 1984 through Mennonite Central Committee on a service assignment with Church and Peace, an ecumenical European peace church network. During this time, he regularly encountered U.S. military personnel stationed in Germany. Through the Church and Peace network, he became acquainted with members of the Christian peace movement in the Hunsrück and was invited to join a small developing ecumenical Christian community in the village of Krastel. He discerned a primary calling for this period to learn to know, understand and love American military personnel working with nuclear weapons. In the fall of 1987, he moved to the Hunsrück and began a second three-year assignment also under the auspices of MCC.

|

The Hunsrück peace initiative was strongly shaped by the involvement and leadership of Christians. The primary ongoing activity was a weekly worship service outside the cruise missile base, sponsored by the Protestant congregation in the village of Bell. A field of 96 crosses was planted adjacent to the base which was to eventually have 96 missiles as a vivid demonstration of different ways of dealing with enemies. The Hunsrück peace movement placed great emphasis on dialogue with those who might be considered opponents. Hours of conversations in church halls and town meetings led to several village councils taking official action in opposition to the deployment of the missiles. Dialogue with villagers who worked for the Bundeswehr (German military) and ongoing conversation with German police who were called on to patrol demonstrations were part of the effort of the local peace initiative. Conversations were conducted at all levels, resulting, for example, in an invitation to participate in a two-day discussion with new recruits at the state police training center. Stoner sought to help cultivate similar avenues of dialogue with U.S. military personnel.

In contrast to Boston and Hill, who made themselves available to soldiers throughout the southern part of Germany and in fact across the entire nation, Stoner primarily related to military personnel at two nearby bases. A further contrast was that while Boston and Hill worked largely with Army personnel, Stoner worked almost exclusively with soldiers in the Air Force. During the first years of his assignment and well into 1990, he had virtually no inquiries from soldiers seeking counseling on discharges or disciplinary measures.

|

Stoner spent these years learning about military culture and building relationships with military personnel at Hahn Air Base and nearby U.S. installations. He sang in the base choir and attended worship services there. He taught German to airmen and their wives, played racquetball with them and hosted American families in his home. His ongoing involvement in the German peace movement was cause for many discussions with airmen, their families, chaplains and even the base commander.15

|

In one respect, however, his work very closely paralleled the work of the other members of MCN. A major priority in his work was to build bridges between American military personnel and Germans in the peace movement, though he focused specifically on the Christian communities in both camps. At meals in his home, for example, Stoner introduced a U.S. missileer and a staff member of the local German peace initiative. He helped Germans from the peace movement join an American Baptist choir to perform a choral cantata by John Michael Talbot, first on the air base and then in a German congregation known especially for its opposition to the cruise missiles.16

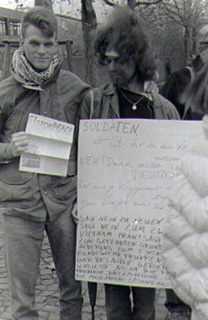

Together with German Christians in the peace movement, starting in May 1988, Stoner began leafleting the Wüschheim Air Station, the deployment site for cruise missiles, and occasionally the larger Hahn Air Base. Every other week, the group of four or five people drafted another leaflet in English and German and passed it out to soldiers and civilian employees as they entered or left the base. The first leaflet explained the weekly worship services outside the base. The other leaflets provided information and perspectives on U.S. foreign and nuclear policy. Some leaflets offered a poem, a prayer or cartoons. Some provided reflections on current events or on significant dates, such as the anniversary of the Nazi German invasion of Poland, U.S. Independence Day or Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday.17

Jutta Dahl, a leader in the Hunsrück peace initiative, wrote in the local peace paper about her experience writing and handing out leaflets in the attempt to make contact with American soldiers. “We break through the feeling of powerlessness, standing outside the base and separated by walls and worlds from what is happening inside. With these leaflets the peace movement is entering into the base. In a small way we are overcoming the walls.”18

At first soldiers were reluctant to take the leaflets, but as the leafleting continued month after month, they noticed and commented if the group missed a week. By early 1990, 100 to 120 people from the base would take a leaflet. The leafletters encountered an occasional snide remark, but then also “Thank you for your presence.”19

|

Stoner collaborated with Hill and Boston to organize a ten-day speaking tour with Vincent and Rosemarie Harding in March 1989. The tour was made possible by grants from two U.S. church and peace groups. The Hardings, who opened Mennonite House, an interracial community center and home to many voluntary service workers, in Atlanta in the early 1960s, had been neighbors, friends and co-workers of Martin Luther King Jr. Vincent Harding had helped draft major portions of the speech King gave exactly one year before he was killed, in which King most strongly condemned U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam.

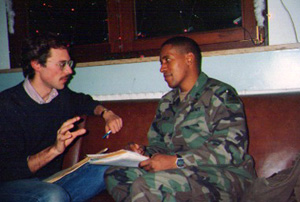

In organizing the speaking tour, MCN staff learned a great deal about how the military operates. They found allies and partners among civilian staff who worked on the military bases. With the help of a sympathetic U.S. Army social worker in Stuttgart, the Hardings were able to meet with leaders of African-American organizations, and Vincent Harding preached at a gospel worship service on base in Bad-Cannstatt. After initial difficulties finding anyone on base willing to host an event in Frankfurt, a University of Maryland professor helped arrange a brown-bag lunch talk in the Abrams complex library. In the end, the base commander attended and the most senior chaplain of the region made a very warm introduction. The Hardings also spoke to a company of soldiers in Ludwigsburg and to high school students at the Hahn Air Base.20

Vincent Harding spoke to military personnel with great candor about King’s “strange notion that you do not make peace with weapons – unless they are the weapons of love, the weapons of courage, the weapons of determination, of compassion.” He reflected together with the soldiers on what it means to honor such a man on a military base with nuclear weapons. Yet rather than judgment, he offered hope and encouragement. Several sessions ended in dreaming together with soldiers about nonviolent alternatives to military force. After their tour, MCN worked with the Hardings to publish a booklet entitled “Mobilizing the Forces of Hope: Reflections on Martin Luther King Jr. and the U.S. Military.” It featured an extended essay by Vincent Harding and the stories of three people who had been in or close to the military whose lives had been changed by King. The booklet was distributed on bases Harding had visited. Not only did this speaking tour generate a host of contacts for MCN staff, the Hardings also demonstrated that frank and meaningful conversation was possible on matters of peace and nonviolence even within the controlled confines of a military barracks.21

In the Hunsrück, conversations between base chaplains and Christians in the peace movement were formalized when Stoner approached the commanding chaplain about the possibility of an ongoing dialogue. The chaplains favored beginning with educational events. As a result, Stoner was invited22 to organize several events through the chapel P.A.C.E. (Program of Adult Christian Education) programs.

|

The first major event in September 1990, entitled “… and the walls came a tumblin’ down!”, featured Friedrich Schorlemmer and Eva and Lothar Löber, leaders in the movement for human rights and peace in East Germany. Thirty American soldiers and family members and 20 members of the West German peace movement met in a room in the base chapel to listen to their guests from East Germany. Because of their common opposition to communism, the U.S. soldiers were receptive to the East Germans’ message of nonviolence in ways they were not to the perspectives of West Germans in the peace movement. Banners brought along from the east –with the same slogans as the peace banners in the west – were hung around the room. Lothar Löber told a story from the Olaf Palme Peace March, when East German Christians were permitted to publicly demonstrate with their own slogans for the first time. At that march, one young member of the Communist youth organization carried an officially sanctioned sign that said: “Work for peace, fight NATO weapons.” A Christian youth beside him held a sign that read: “Work for peace without weapons.” After the presentation at Hahn Air Base, extended informal discussion followed.23

|

The planning of this event was complicated when Stoner was informed by the chief chaplain that he was barred from base due to his involvement in peace movement activities.24 He was later told this had been a mistake and was able to participate in the P.A.C.E. event but shortly thereafter was in fact barred from base. With the buildup toward the first Gulf War, opportunities for dialogue diminished.

Financial support for the broader work of MCN continued to be a challenge. This was especially true for Boston and Hill. André and Cathy Stoner continued to receive room, board and a small stipend from MCC. Their term of service was due to end in early 1991, however. Boston had decided to pursue a career in journalism, which took him out of the area where U.S. military personnel were stationed. At an August 1990 meeting, MCN counselors “decided to fold shop.” Some of the individuals who had received military counselor training and who remained in the country would still make themselves available to assist the occasional soldier, but any coordinated outreach effort would not continue. The office in Stuttgart was closed.25

But the course of international events pressed new opportunities and challenges on the counselors who remained. At the beginning of August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. The United States and allied countries responded with a massive military buildup in the Persian Gulf region. Germany, rather than being a deployment site for nuclear weapons was now a primary staging ground for thousands of troops and a major military confrontation. On Nov. 10, 1990, U.S. Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney announced that new U.S. troop deployments to the Persian Gulf would include half of all American land forces in Europe, roughly 100,000 men and women.

As the buildup continued in the Gulf, the leafletters in the Hunsrück wrote some fliers specifically addressing that situation. Several leaflets included information about conscientious objection and other discharges with reference to particular Army regulations. They included a contact address for MCN, using the address of the Hunsrück Peace Initiative and the private phone number of André and Cathy Stoner.

Through an informal network of friends and acquaintances, copies of these newsletters were sent to other local peace initiatives. Some of these groups reproduced them and began handing them out to U.S. soldiers in their communities. This was one very concrete action available to Germans opposed to the war. Regional press reported on peace movement efforts to reach U.S. soldiers. A Nürnberg paper, for example, printed an article with a picture of a poster that included the MCN phone number.26

Suddenly MCN counselors were inundated by calls for help from GIs. “We could tell where peace people were handing out leaflets. Two or three days later, the calls would start coming in from that area. First it was Bremen, then Ansbach, then Frankfurt and on and on,” Cathy Stoner remembers. Generally, the Stoners provided information over the phone about military regulations and discharge procedures. When possible, they met with soldiers to discuss their case in person. Many inquired about conscientious objection. Some pursued alternative discharges. In several cases, soldiers sought to harm themselves to cause hospitalization and to prevent deployment. Many calls came from concerned wives or German girlfriends.27

|

In early December 1990, Erik Larsen came to Germany to speak at a large anti-war rally in Bonn. Larsen was a U.S. Marine reservist and an outspoken critic of the war buildup. He spoke forcefully and eloquently of his refusal to participate in the war. After the demonstration, he met with the Stoners, who told him about some of the soldiers they were counseling. Many were isolated from personal support. Larsen decided to delay his return flight to the United States and travel with André Stoner to visit some of these young men and women. He made stops in Bitburg, the Hunsrück, Frankfurt, Nürnburg, Ansbach, Stuttgart and elsewhere. At each place, he met with American soldiers, Germans in the peace movement and the German press.

At one stop, three Black GIs from a tank division told of the deep suspicion among Black soldiers of the war buildup. Many anticipated getting sent to the front line to face Iraq’s chemical weapons. Some surmised that this was a plan to get rid of the large number of Black soldiers who would soon be unemployed as a result of troop drawn-downs with the end of the Cold War. Soldiers were doing everything they could to slow their deployment to the Arabian Desert. They missed their appointments to get a dental imprint to identify the dead on the battlefield. They delayed writing their wills. Tanks were already being shipped by rail to various harbors for transport to the Gulf. One of the soldiers suggested that German peace activists block the rails in solidarity with troops who did not want to fight.28

|

The whirlwind tour with Erik Larsen generated increased interest in the German peace movement about the plight of U.S. soldiers opposed to the war. Stoner was able to meet personally with Germans who had been distributing fliers at military bases. Invariably, Larsen and Stoner were hosted by a local affiliate of the Green Party or a pastor or peace group strongly rooted in the Protestant church. In several locations, German hosts requested an MCN counselor to help provide follow-up for the GIs with whom they were in contact.

Meanwhile in Worms, Darnell Summers, a U.S. Army veteran, was working with other vets, several active-duty soldiers and others to produce a rap about the war. The professional quality piece, “Just Say No!” was a militant rejection of the Gulf War.

Read the newspaper just the other day –

heavy storm clouds are moving our way.

(They) want to send me to the desert to play a deadly game,

armed to the teeth, ready to murder and maim.

Got no say in this matter – did you ask how I feel?

Chumps like me a dime a dozen –

think we don’t know the deal?

I ain’t dying for the price of gas.

Yo, Uncle Sam, you can kiss my ass …

Don’t wanna be a hero, can’t stand John Wayne;

to go and die for you – I’d have to be insane.

There’s no glory in disaster

once the wheels of war start to turn.

Tell me, what’s the next step, sucker,

when the oil fields start to burn?

New York, Paris, London, Rome –

young men and women dragged away from home.

Sydney, Berlin, Baghdad, Tel Aviv –

facing off at each other for the Sultans of Greed.

Brothers will be dying – mothers will be crying!

And what’s it all for? Just another rich man’s war! …

They’d like to have us believe they’re defending democracy.

But anyone with eyes can see – that’s a fallacy.

Saudi Arabia’s not a democratic state –

the women on the street can’t even show their face…

So when they tell you to go,

just say no … 29

The tape achieved modest circulation, but where it was heard, the impact was electrifying. It received national attention in a Stern magazine article on GI resistance to the war that featured the work of MCN.30 For many peace activists, finding such outspoken critics of war policy within the military ranks was a revelation. While some had begun to see soldiers more as victims than as enemies, the “Just Say No” tape, the Erik Larsen visit and contacts with soldiers who were refusing deployment led them to regard soldiers as potentially powerful allies in the struggle to stop the war.

Already in November, the Stoners had put out an appeal to military counselors in the United States to help them work with GIs stationed in Germany. The request to the MCC Peace Office made its way to Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder, teaching at the University of Notre Dame. He passed the request on to acquaintances in Catholic peace networks. As a result, in December six individuals, one Mennonite and six Catholic, flew to Germany for 10 to 14 days. A counselor from the International Fellowship of Reconciliation also traveled from the Netherlands to help. The German church and peace groups that had been handing out fliers at military bases and had been visited by Erik Larsen opened their offices and provided housing, translators and other support for these counselors. They were scattered across the country from Bremen to Nürnburg.31

As deployment neared, The Stars and Stripes, the “authorized unofficial publication for the U.S. Armed Forces,” ran a front-page article and a two-page spread on the work of MCN and conscientious objection. The articles explained the procedure for filing a CO discharge and featured two conscientious objectors, Henry Spielberger and Jonathan Bruce, who had received assistance from MCN in processing their claims. One of the articles did a profile on Shelley Anderson, a veteran herself and one of the seven American counselors who traveled to Germany for two weeks to assist MCN.32

|

During the war buildup, MCN continued to assist men and women such as Spielberger and Bruce whose CO claims were accepted and processed, albeit with some irregularities, by the U.S. military. This often involved reviewing the discharge claim with the conscientious objector, helping assure that claims were properly handled (including placing claimants on noncombatant duty) and attending CO hearings. As deployment to the Gulf became imminent, however, MCN counselors were faced with an entirely new set of challenges.

The case of Addis Wiley is illustrative. Wiley was on disciplinary confinement in his barracks when he saw an MCN flier pinned to a bulletin board and scribbled with numerous derogatory comments. He called the number on the flier and reached Dennis Koehn, one of the seven short-term MCN counselors, who was working out of the Frankfurt office of the Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft-Vereinigte KriegsdienstgegnerInnen (DFG-VK).33 Wiley had been a star soldier – an African American from Staten Island, N.Y., he had advanced to the rank of sergeant in 2½ years. He served in the 3rd Armored Division as a driver of a Bradley fighting vehicle.

But a conversion experience in a Pentecostal congregation during leave in the United States changed all that. When Wiley called Koehn, he stated simply: “I cannot walk with Jesus and go to war.” Several days earlier, he had told his commander the same thing. The captain was outraged. He shouted Wiley down and threatened to have him court-martialed for fraudulent enlistment. Wiley was not informed of the proper procedure for filing as a CO. A day after Wiley handed in a written request for a CO discharge, his first sergeant denied having received anything. Wiley was confined to barracks for two weeks because he missed a formation while seeking to meet with a civilian attorney. It was at this point that he contacted Koehn.

Koehn informed him of the proper procedure for filing a discharge and explained how he could formally complain about his treatment. He was denied admittance to the barracks to meet with Wiley, however. With Koehn’s counsel, Wiley began to prepare his discharge claim.

|

Exasperated by the improper processing of his CO claim, Sgt. Wiley left his duty post in late December. He was not alone. MCN was in contact with several dozen soldiers who made similar choices. After 58 hours, Wiley returned voluntarily with a completed conscientious objector packet in hand. Upon his return, he learned that his unit was deploying to Saudi Arabia. He requested to be joined to his unit to serve as a noncombatant until his claim was processed. His request was denied and instead he was charged with going AWOL and missing troop movement. Several weeks later, the much more serious charge of “desertion with intent to avoid hazardous duty” was added. MCN counselors assisted in procuring experienced legal aid. Wiley was eventually court-martialed and served an eight-month sentence.34

The manner in which Wiley’s CO claim was handled was not unusual. Several administrative orders by Army officials exacerbated the situation. A “stop loss” order issued in October meant that soldiers whose unit was on alert could not file claim for a CO or other discharge until their unit reached its new destination. As a result, CO claims submitted in Germany were routinely refused, disregarded or in at least one case simply torn up. In a somewhat contradictory step, U.S. Army Europe Commander Gen. Crosby Saint ordered that CO claims be processed more rapidly. As a result, some GIs were given as little as four hours’ notice of their CO hearings, insufficient time to bring counsel and gather witnesses.

Furthermore, many commanders were simply unaccustomed to processing CO claims and unfamiliar with proper procedure. Commanders told COs they could not apply if they were not religious or during times of war. One commander in Kitzingen lectured his troops that anyone filing for CO status would be court-martialed. Numerous COs told MCN counselors they had received death threats, on some occasions from members of their own chain of command.

Derrick Jones, an Army medic from North Dakota and a Baptist, had called the Stoners in early December and filed for CO status shortly thereafter. Some years earlier, he had seen casualties of the Panama invasion and at that time began questioning if he could participate in combat in light of his Christian faith. When he submitted his discharge claim, he told a chaplain that he could not kill another member of the body of Christ. Jones learned that his unit was to deploy for war shortly after Christmas. After an intense personal struggle, he went AWOL.

Five days later, Jones contacted his captain through an attorney. In a phone call, the officer encouraged Jones to return to his unit and, after consulting with his superiors, assured Jones that though he would be disciplined for his absence, he would not be deployed to Saudi Arabia. At 4 p.m. Jan. 2, 1991, Jones returned to his unit in Friedberg, accompanied by his lawyer and anticipating an eventual jail term. He was promptly handcuffed, harshly questioned and driven to Rhine-Main Airport. By 9 that evening, he sat in a state of shock on a plane bound for the desert.

Jones was one of five COs of whom MCN counselors were aware who were forcibly deployed from Germany to the Persian Gulf, several like Jones in handcuffs and even leg irons. This was reported on the front page of the Frankfurter Rundschau and in other news magazines. Amnesty International adopted at least three such Gulf War conscientious objectors as prisoners of conscience. In Saudi Arabia, Jones received non-judicial punishment for being AWOL. He was given noncombatant duties and granted a CO hearing, though without the presence of a CO counselor. He was forced to advance with his unit through Iraq and into Kuwait. He eventually returned to Germany to await the decision on his CO claim. To the best knowledge of MCN counselors, that claim was denied and Jones decided to wait it out and finish his term of service.35

MCN also counseled selective objectors who did not qualify as conscientious objectors under military regulations. These soldiers objected to this particular war, but not necessarily to all wars. Several African-American Muslims, for example, objected to the possibility of killing Muslim brothers and sisters. Some of these men and women, who saw no legal recourse, also left their units.

|

Wiley and other soldiers who left their units were assisted by a network of Protestant clergy and Green Party members. Numerous families opened their homes to AWOL GIs and transported them from place to place. This came at a time when the German public was debating whether World War II deserters should be honored. In conjunction with that debate, several regional Green Party leaders publicly encouraged U.S. soldiers to “take a winter vacation.” In Bremen, more than 200 prominent citizens – including professors, doctors and lawyers – declared in a newspaper advertisement: “I am prepared to offer hospitality to U.S. soldiers who leave their units.” This resulted in police raids on some Green Party offices. In December, the German television program Monitor interviewed a series of TV and movie stars and other celebrities, all of whom said that of course they would shelter any GI who came to their door.36

A Green Party leader organized a clandestine meeting to discuss support for AWOL soldiers. People from the entire country gathered, discreetly receiving instructions at a train station to make long circuitous approaches to the meeting site. “The cloak-and-dagger atmosphere was almost comical,” remembers Cathy Stoner. “We appreciated the concern and support for the soldiers, but sometimes felt the Greens were using the soldiers for their own purposes. For us, for example, the distinction between going AWOL in order to prepare papers for a discharge application and deserting one’s unit was very important. This didn’t fit the current German debate and never seemed to register with our partners in the Green Party.”

In the six months of the war buildup from August 1990 until January 1991, MCN counselors took calls from more than a thousand U.S. soldiers, family members or girlfriends. During this time, they assisted roughly 70 GIs in filing CO claims (compared to the eight cases in the previous four years) and counseled several dozen AWOL soldiers. Around another 15 received assistance as they filed for discharges or re-assignment on medical grounds or for hardship reasons.37

After the troops were deployed, MCN counselors continued to assist soldiers who remained in Germany. André and Cathy Stoner extended their term of service with MCC until the end of April 1991. In March alone, they together with other MCN counselors assisted more than 10 soldiers at their CO hearings.38

MCN struggled, however, to assist GIs who had gone AWOL and were now facing legal proceedings. They sought to publicize the plight of forcibly deployed COs and AWOL objectors and succeeded in getting coverage of this situation in major U.S. and German publications.39 MCN further decided to begin a short-term legal project. Though there were civilian U.S. attorneys in Germany knowledgeable in military law, MCN counselors and the soldiers with whom they were working did not have confidence in their independence of military command and their understanding of the issues involved with conscientious objection. Therefore, MCN decided to invite several lawyers from the United States to come represent the AWOL COs as they returned to their units.

The Legal Project stretched the financial and organizational resources of MCN to the limit. To help cover expenses for the Legal Project, the DFG-VK Frankfurt group extended MCN a DM 17,000 loan.40

The MCN Legal Project, based in the offices of the War Resister’s League in Frankfurt, provided services to approximately 35 U.S. Army soldiers. Three lawyers participated in the project. Two stayed for one month, with one returning for an additional two weeks to finish a court martial. The third lawyer stayed for five months. The attorneys assisted seven soldiers returning to their units after having been AWOL. Four were court-martialed and three were administratively discharged. In MCN-assisted court-martial cases, sentences ranged from four to nine months. MCN staff was aware of other court-martial cases in Germany where conscientious objection was part of the defense that received up to 27-month sentences. A number of cases involved medical and psychological issues rather than conscientious objection.41

Roughly 30 of the AWOL soldiers found their way to an out-processing unit in Fort Dix, N.J., and simply received “other than honorable” discharges. As units returned to Germany from the Gulf, however, they were calling soldiers back to Germany to personally try and sentence them. “Given the present climate, we are talking about the most unpopular defendants in the country at this time,” said Clare Overlander, one of the MCN staff attorneys. “There is a strong attitude of retribution within the Army in Germany these days.”42

During 1991 a coalition of agencies joined together to sponsor the work of MCN. They included Ohne Rüstung Leben, DFG-VK Frankfurt, Pax Christi Stuttgart, the Baden Würtenberg chapter of the Bund deutscher katholischer Jugend (Federation of German Catholic Youth), and the Katholischer Arbeiskreis für Kriegsdienstgegner (Alliance for Catholic War Resisters). Representatives of these organizations and several Americans living in Germany who had been long-standing supporters of MCN formed a board for the organization.43

Cathy and André Stoner returned to the United States at the end of April 1991. Clare Overlander, staff attorney, and Michael Erlich, a college friend of Cathy Stoner’s who had been working for MCN out of the Frankfurt DFG-VK office, continued the work for several months until Rebekah Trumper, a Brethren Voluntary Service worker began a two year term of service as MCN coordinator. Janice Hill continued to volunteer time based out of her home near Tübingen.

After the urgency of the war had receded, significant effort was again required to generate funds, both for the on-going work and to eliminate the debt incurred to run the Legal Project. While MCN had received sizeable contributions from German groups immediately before and during the war, it was now once more in “the space between” German and American groups. As MCN counselors perceived it, despite generous support from German groups, Germans regarded GIs as an American problem. The American groups, on the other hand, already felt overextended. GIs in Germany seemed too far away for them to become involved. A 1991 funding proposal detailed the important advances the organization had made during the past year: a larger more experienced network of counselors; contacts within the military; media recognition; a stronger organizational structure; and support within the German peace community, which “is beginning to see the face behind the uniform.” Nonetheless, no significant source of stateside funding was found. 44

Vic Thiessen became MCN coordinator in 1993 as a volunteer through MCC. Thiessen devoted considerable time to outreach and dialogue among Christians in the military. A June 1993 MCN newsletter reported that a small advertisement, run presumably in a military newspaper, resulted in 30 calls and 20 counseling cases. Most cases involved filing complaints about harassment or ill treatment by superiors. There were no CO cases. MCN also initiated a prisoner visitation program with the NAACP and a Listening Project with Heidelberg soldiers.45

BVSer Suzanne McKenzie assumed the coordinator role in the fall of 1994. By early 1995, there had long been no active CO counseling cases. MCN counselors did not favor assisting soldiers on matters other than discharges. At a May 13 meeting of MCN counselors, it was decided “that MCN be disbanded as a coordinated organization and remain only as a passive network of connected individuals” which could be reactivated in the case of a future war or increased inquiries from soldiers.46

Indeed, after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and the launch of the Iraq War, Germany was again a staging ground for the U.S. military’s war efforts. Again, American soldiers struggled with questions of conscience. Building on the experiences of the first Gulf War, the German Mennonite Peace Committee revived the Military Counseling Network. With the help of a steady stream of North American Mennonite volunteers supported by MCC and Mennonite Mission Network, hundreds of GIs again received counsel and support.47

The response of the German peace movement to U.S. military personnel differed significantly during the debate about intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) in Europe during the 1980s from the movement’s attitude toward American soldiers during the first Gulf War just a few years later. Most of the focus during the INF debate was on technical matters concerning the new generation of nuclear weapons. Local peace initiatives in places like the Hunsrück scoured Army documents and transcripts of debates in Congress and in congressional subcommittees to learn where the new weapons would be deployed, what their capabilities were and to what extent they represented a shift in strategy toward a first-strike capability. Massive demonstrations, human chains and blockades of bases by senior citizens, prominent personalities and concert musicians in performance captured the nation’s attention and helped mobilized public opinion. There was, however, very little engagement with the American men and women in uniform who worked with the missiles and on the airfields. The most common refrain with regard to U.S. soldiers was “Ami, go home!”

During the Gulf War and the buildup to the war, significant parts of the peace movement developed an entirely different posture towards U.S. GIs. The Military Counseling Network, with strong support from Mennonites in the United States and Germany, played a significant role in this shift. Now Germans sought contact with U.S. soldiers at dozens of bases through leafleting and drop-in centers. Major demonstrations featured U.S. soldiers or veterans opposed to the war. Movement newsletters and the popular press featured interviews with GIs who were filing discharge claims or had gone AWOL. A network of church and peace groups offered housing and transportation to soldiers who left their units. Others hosted American peace workers who traveled to Germany during the holiday season specifically to offer support and counseling to GIs who had questions about their involvement in the war. No longer were GIs simply regarded with hostility as pawns of the enemy. Now they were seen as people with more complex stories and interests who could, in fact, become potential allies. As one sign at a demonstration read: “We love your faces, but not your bases!”

1. Military Counseling Network, “Request for Funding of the Military Counseling Network,” 1988, 2. This document was sent to peace and church groups in the United States. It, along with the other MCN documents mentioned, is in the author’s private collection.

2. Military Counseling Network, “Military Counseling Network W. Germany” brochure.

3. MCN, “Request for Funding,” 1.

4. André Gingerich Stoner began his MCC assignment as André Gingerich. In late summer 1989, he married and took the name André Gingerich Stoner. He and his wife, Cathy Stoner, returned to Germany in November 1989 and together completed their term of service through the spring of 1991.

5. MCN, “Request for Funding,” 2.

6. André Gingerich, “Quarterly Report March-June, 1988” to Mennonite Central Committee, July 9, 1988, 4.

7. Ohne Rüstung Leben (Living without Weapons) is a leading organization in the German Christian peace movement that takes its inspiration from a declaration of the World Council of Churches, gathered in Nairobi in 1975, that “The churches should emphasize their readiness to live without the protection of armaments, and take a significant initiative in pressing for effective disarmament.”

8. MCN, “Request for Funding,” 2.

9. The Bridge, no. 1 (Feb. 1989).

10. MCN, “Request for Funding,” 5.

11. Ibid.

12. André Gingerich Stoner and Cathy Stoner, “Quarterly Report of André and Cathy Stoner, Mid-Nov. ’89-Feb. ’90,” to Mennonite Central Committee, Feb. 26, 1990.

13. “German Protestants Support ‘Women and the U.S. Military,’” The Bridge, no. 2 (June 1989), 2.

14. MCN, “Request for Funding,” 1.

15. André Gingerich Stoner, “Entering Samaria: Peace Ministry among U.S. Military Personnel in West Germany,” MCC Occasional Paper No. 12. Mennonite Central Committee, Akron, Pa., Sept. 1990.

16. Ibid, 4, 15.

17. Collection of leaflets in author’s possession.

18. Jutta Dahl, “Flugblattaktionen vor Wueschheim Air Station: Ein Versuch der Kontaktaufnahme mit amerikanischen Soldaten,” author’s translation, Hunsrück Forum, 25/89, 33.

19. “Quarterly Report,” July 9, 1988, and “Quarterly Report,” Feb. 26, 1990.

20. “Entering Samaria,” 27.

21. Vincent Harding, “What Kind of Man was He?” The Bridge, No. 2 (June 1989), 4; “Entering Samaria,” 28; Vincent and Rosemarie Harding, Mobilizing the Forces of Hope: Reflections on Martin Luther King Jr. and the U.S. Military, Mennonite Central Committee and Military Counseling Network, Oct. 1989.

22. André Gingerich Stoner, memo to Chaplain Alex Roberts, March 10, 1990; Gary Macy, Chaplain, U.S. Air Force, letter to André Stoner, April 5, 1990.

23. Hahn Air Base Chapel, P.A.C.E. Summer Quarter, 1990 Catalogue, 4; Wolfgang Bartels, “US-Soldaten und Christen aus dem Hunsrück erfahren gemeinsam: In der DDR hat das Prinzip der Gewaltlosigkeit gesiegt,” press release.

24. Letter from Jutta Dahl and André Stoner to Hahn Air Base chaplains, Sept 7, 1990.

25. André Gingerich Stoner and Cathy Stoner, presentation at a conference of the National Interreligious Service Board for Conscientious Objectors, Washington, D.C., July 1992; MCN, “Funding Proposal for the Military Counseling Network, Germany,” 1991.

26. “Nackte Angst vor Selbstmordeinsatz,” Nürnberg Land und Region, November 12, 1990, 17.

27. Cathy Stoner, interview, South Bend, Ind., Sept. 2, 2000.

28. Christian Peacemaker Teams, Signs of the Times, Dec. 1991, 2.

29. Darnell Stephen Summers, “Just Say No,” August 1992.

30. Charlotte Wiedemann, “Dem Krieg den Dienst Verweigern,” Stern, 12 January 1991, 32-33.

31. “MCC Workers and Others Continue Military Counseling in Germany,” MCC News Service, Jan. 4, 1991.

32. Ron Jensen, “Counselors ‘Overwhelmed’ with Calls on Objector Status”; Jensen, “Former GI Explains His Conversion”; Effie Bathan, “Ex-Servicewoman has Found Niche Advocating Peace”; all in Stars and Stripes, Dec. 16, 1990, 1, 9, 10.

33. The German affiliate of the International War Resisters League

34. André Gingerich Stoner, “Statement in Support of an Amnesty for Imprisoned Conscientious Objector,” submitted to Congressman Ron Dellums, July 24, 1991; Stoner, NISBCO presentation, July 1991.

35. Stoner, NISBCO presentation, July 1991; Michael Ryan, “The Call to Arms has Sounded – But for Love of Peace, or Fear of War, Some Soldiers Are Just Saying No,” People, Feb. 4, 1991, 47-50; Pin von Bebenburg, “In Handschellen an den Gulf,” Frankfurter Rundschau, Jan. 5, 1991; Jim Rice, “On the Front Lines of Resistance,” Sojourners, April 1991, 26-29; Stoner, “Statement in Support of an Amnesty.”

36. Stern, 33; Bruce Shapiro, The Nation, “Hell for those who won’t go,” Feb. 11, 1991, 196.

37. Stoner, NISBCO presentation, July 1993; Rebekah Trumper, MCN appeal, “American COs in Germany Face Jail Sentences,” July 1991; MCN “Funding Proposal for the Military Counseling Network, Germany,” 1991.

38. Funding Proposal, 1991.

39. Barbara Reynolds, USA Today, “Chains for those who refuse to fight,” Feb. 8, 1991, 13; Marc Fisher, The Washington Post, “The Army’s Conscientious Question,” Feb. 9, 1991; The Nation, “Hell for those who won’t go;” People, Feb. 4, 1991, pp. 47-50; Pin von Bebenburg, “In Handschellen an den Gulf,” Frankfurter Rundschau, Jan. 5, 1991; Hans-Helmut Kohl, “Manchem Verveigerer geht es schlechter als Kriegsgefangener,” Frankfurter Rundschau, April 12, 1991.

40. André Gingerich Stoner, “Brief Overview of MCN Financial Situation,” Sept. 17, 1991.

41. Clare Overlander, report, July 22, 1991. Overlander was the staff attorney who worked with MCN for five months. This report is in author’s possession.

42. Rebekah Trumper, “American COs in Germany Face Jail Sentences”; Overlander report.

43. Funding Proposal, 1991.

44. Funding Proposal, 1991.

45. Randy Shank, ed., Military Counseling Network News, June 1992.

46. MCN, minutes of May 13, 1995; Suzanne McKenzie, letter to “counselors, sponsors, friends and alumni of MCN,” May 16, 1995.

47. This story is told in part in Peace Office Newsletter, 38, no. 1 (January-March 2008), Mennonite Central Committee Peace Office publication.