Felipe Hinojosa is assistant professor of history at Texas A&M Universityin College Station, Texas. He has teaching and research interests that include Latina/o-Chicana/o studies, American religion, social movements, gender, race and ethnicity. He was recently awarded a “First Book Grant for Minority Scholars” from the Louisville Institute and is working on a book manuscript titled “Quiet Riots: Faith, Activism, and Identity Among Latina/o Mennonites, 1932-1982.”

In 1977, Antero “Sonny” Rodriguez graduated from Eastern Mennonite College in Harrisonburg, Va. Far from his hometown of Alice, Texas (located about an hour west of Corpus Christi), Rodriguez was one in a long line of Mexican Americans from South Texas who entered Mennonite institutions in the 1960s and ’70s. His good friend, Dan Bueno, was attending Goshen (Ind.) College at the time and was a star athlete on the cross-country team. Right after he graduated, Rodriguez published a poem in the EMC Bulletin that reflected his politics both as a Mexican American and a Mennonite. The poem covers a conversation between two seeds, one a “brown” seed (Mexican-American youth) and the other a “Christian” seed (presumably Jesus Christ). In the poem, Christian Seed speaks of love and forgiveness, to which Brown Seed responds:

Love! Huh! snapped brown seed. How can you speak of love when my fellow seeds, old and young, labor on hot summer days, pulling weeds from crop fields for ridiculous wages! How can you talk about love when my brothers are being killed in wars created by white seed?... is it love when white seed taunts me about carrying knives and guns as if I were some dangerous creature? How can it be love when white seed treats me like dirt?1

Rodriguez’s poem is reflective of the experiences of many Mexican Americans who grew up in South Texas and were often treated as second-class citizens. In the 1930s, historian Paul Taylor called this part of Texas an “American-Mexican frontier” where cultures intersected and where white supremacy kept many Mexican Americans on the lower end of the pay scale.2

During most of the 20th century, segregation and discrimination against Mexican Americans in South Texas rested on the back of a booming agriculture and oil industry that helped transform many small towns, including Alice and nearby Mathis.3 Between the 1930s and 1960s, Mathis and Alice saw growth in the Mexican-American population as both communities moved from ranching and livestock to growing and transporting fruits and vegetables. The need for labor brought many Mexican Americans to these towns in search of more stable work. U.S. census records show Mathis’ population jumped from 1,950 in 1940 to 6,075 in 1960.4 But no other town in the area experienced the growth that Alice did between 1930 and 1960. In 1938, an oilfield discovered in Alice sealed its fate as “the Hub City of South Texas.” As a result, its population had surpassed 20,000 by 1960. Many of the newfound resources, however, stayed firmly in the hands of the Anglo elite.5

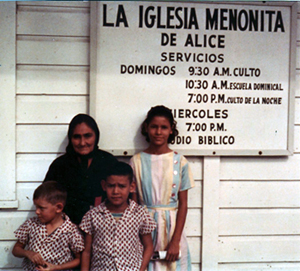

It is no surprise, then, that as Mennonite missionaries struggled to gain a following in South Texas in the 1930s and ’40s, they moved their church planting operations to Mathis and Alice.6 In 1952, the first three Voluntary Service workers arrived in Mathis. By 1958, Norma and Joseph Hostetler had moved to Alice, where they organized a summer Bible school and helped start a church which, once organized, attracted somewhere between 40 and 60 people every Sunday morning.7 By May 1963, South Central Conference of the Mennonite Church had officially recognized Alice Mennonite Church. March 21, 1965, traveling evangelist Jacinto Muñoz Becerra delivered the sermon at a dedication service for the church.8

|

La Iglesia del Pueblo/The Church of the People

Almost from the beginning, the Mennonite church in Alice was different. As longtime church leader and high school teacher Dan Miller remembered, “Alice was more social than evangelical… VS couples who did not align with the ‘social gospel’ of our church did not last long.”9 The VSers who did embrace the social gospel were also quite aware of how racism operated in South Texas. Of the racial tension between Anglos and Mexicans, Miller wrote:

This city [Alice] has divisions, walls – many of them have their roots in the race problem. I meet people in the Chicano community as well as the gringo community who would like to see these walls come down and don’t know what to do. It is like if we were running a race and have the same starting line but the other person has his legs cut off.10

Miller’s words were not an exaggeration. In a 1967 report from the Texas State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights, investigators commented on the rampant discrimination against Mexican Americans across South Texas. Apolonio Montemayor, a staff representative of the United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO, told the committee: “I don’t believe there’s any question in anyone’s mind that there is discrimination in employment against the minority Mexican in every field… when you find jobs that are very badly paid, and poor benefits, then there is the Mexican. This is in the fabrication industries, laundries, bakeries. They don’t discriminate in hiring, they discriminate when it comes to paying.”11 In almost every area, from education to voting to employment, Mexican Americans struggled to gain a stable footing under the racist practices of Anglos in South Texas.

The church, however, was one of the few free spaces that allowed Mexican Americans room for reflection and a space to build community and develop leadership skills.12 In Alice, no one did this better than the small group of Mexican-American and Anglo Mennonites who attended Alice Mennonite Church. Located on the west side of Alice just outside the city limits, in the heart of the Rancho Alegre barrio, Alice Mennonite Church was the only Protestant church in the area. In the barrio, one of the poorest sections of the city, it was only the Mennonites and the Catholics. After some early issues of trust between the congregations, they forged a partnership that revolved around the desire to help improve the lives of Mexican-American youth.13

This meant that church activities hosted by the Alice Mennonite Church often attracted a good number of young people who otherwise would not have attended the church. When South Texas Mennonites gathered for youth events, Alice Mennonite Church usually showed up with a strong contingent of community youth, to the dismay of many who worried the “un-churched” would only cause problems.

Alice Mennonite also opened its doors to community activist groups such as the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) in the early 1970s. When MAYO needed a place to print their small newspaper, they naturally looked to the Mennonite church in Alice. This affiliation often drew the suspicion of school officials, who at one point asked Dan Miller to explain why a group of young activists was printing its newspaper at the church. Miller denied any association and simply stated that the youth used the church to print the newspaper and nothing else. Regardless, Alice Mennonite Church was already seen by many as a progressive church that cared more about social justice than saving souls.14

What made Alice Mennonite Church different was not only its ability to relate well to community members – it was also the only Mennonite church in the area to have prominent Mexican-American leadership. In contrast to the center of Mennonite missions in nearby Mathis, the Alice church alternated between Mexican-American and Anglo leadership. During its first 20 years as a congregation, between 1958 and 1978, the church had three Mexican-American pastors – S.V. Zapata, Raul Tadeo and Tito Guedea. Allen and Bernelle Kanagy and Joe and Norma Hostetler also led the congregation during this time but usually for short periods. During this same time, all the other Mennonite churches in South Texas had Anglo pastors (with the exception of the new church in Brownsville, started in 1971 by Conrado Hinojosa). In this regard, Alice Mennonite Church was ahead of its time. The prominent Mexican-American leadership in Alice is even more impressive when you consider that, during the late 1960s, many African-American and Latino Mennonite churches across the country struggled to move away from Anglo pastoral leadership.15

|

“It keeps the kids off the streets”: The Rancho Alegre Youth Center

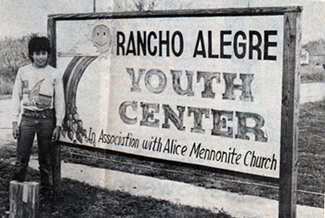

Five years after Alice Mennonite Church was organized, the congregation celebrated the opening of a community center for youth known as Rancho Alegre Youth Center, located in the same neighborhood as the church and developed on a four-acre park and recreation area. RAYC opened with cooperation and help from the community, city, county, businesspeople and other churches. It received funding from Mennonite Board of Missions, the black and Latino Minority Ministries Council of the Mennonite Church and other Protestant churches in Alice.16 In 1972, funds were allocated in the Jim Wells County budget after church members attended a county court session to advocate for funds for the RAYC. This was not the first time the group had appeared before the county court. They had already successfully lobbied to have the city of Alice restore water services after cutting off the water supply shortly after the RAYC opened in 1968.

|

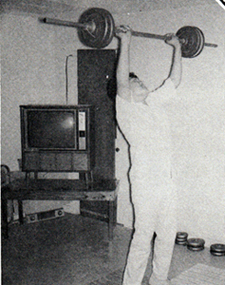

Everyday activities at the RAYC included a boys club, girls club, arts and crafts program, Bible quiz competitions, volleyball and softball games and a very popular weightlifting program. On any given day, more than 20 teenagers gathered to lift weights, often competing to see who could lift the most. For Lisa Guedea Carreño, memories of the RAYC revolve around the activities that provided youth with something to do to pass the time under the hot South Texas sun. During her middle-school years in the mid-1970s, Guedea Carreño played on a girls softball team appropriately called “Las Chicanas,” made up entirely of young women from the Rancho Alegre barrio. Practices and games were always at the RAYC. “We were in a citywide league,” Guedea Carreño remembered, “that played against teams from other neighborhoods… We weren’t the best team in the league, but we had a lot of ganas, that’s for sure.”17

|

Aside from games and sports, the RAYC was a place for youth to hang out, shoot some pool, talk about the upcoming football game or share stories of the migrant trips north that many took with their families to make ends meet. And while the youth understood this was a church ministry, it did not stop them from occasionally engaging in deviant behavior – such as the time pastor Tito Guedea found a small bag of marijuana (“grass,” as the guys called it) stuffed into a crevice under the welcome sign in front of the building. “‘Well, if it’s grass, then it belongs on the ground,’ [he told the guys], and he promptly [dumped the contents of the bag],” Guedea’s daughter, Lisa Guedea Carreño, remembered. She also recalled seeing “little bits and pieces of pot flying every which way in the wind.”18

Church ministries like the RAYC were nothing new among Mennonite Voluntary Service programs in South Texas. In nearby Mathis, Mennonite VSers organized an extremely popular maternity clinic in the early 1950s that addressed the high infant mortality rates common in South Texas. Around the same time, they started a kindergarten program that helped Mexican-American children learn English in order to move on to first grade. Public schools in Texas were notorious for holding Mexican-American children in kindergarten for as many as three years. By the time children arrived in first grade, they were eight or nine years old. The state claimed it was because the children did not speak English, but Mexican-American activists such as Dr. Hector P. Garcia proved it was actually an extension of Jim Crow segregation into South Texas schools.19

As popular as the maternity clinic and kindergarten program were, Anglos in Mathis and some of the white Mennonite leadership never allowed them to develop and grow into their own entities, separate from VS. As a result, both programs closed during the middle part of the 1960s. What made the RAYC different was that it received broad support from community members, politicians and other church groups in Alice. The RAYC was the only Mennonite program in South Texas that extended well into the 1990s, meaning it served the community for more than 20 years. This was a direct result of the support it received from community groups in Alice. In the mid-1980s, much of the funding came from the local branch of the United Way, Jim Wells County, the Catholic church and individual donors like Juan Suarez, who in 1985 gave funds for baseball equipment. It was all to benefit the more than 50 youth who visited the center every day, with even more during the summer months.20

|

The visibility of RAYC and its reputation for helping youth by keeping them busy made quite an impression on barrio residents like Lupe Lozano. He commented to the local newspaper that RAYC “keeps a lot of kids off the street late at night.” He went on to say that the youth at RAYC “are good kids, but they do need a lot of attention. Somebody to show them that there are a lot of ways to be happy.”21 In fact, there was so much local support that when Jim Wells County turned down a proposal from Wayne and Emma Beachey to help fund the RAYC in 1984, county treasurer Adan Valadez donated a 400-pound calf to the RAYC for a barbecue fundraiser. The following year, local politicians lined up to participate in the “Political All-Stars softball game to benefit Rancho Alegre Youth Center” in which county attorneys, the city manager and county commissioners all participated. Well into the 1980s, Mennonite Board of Missions continued to provide its share of funding for the RAYC along with community and church groups in the city of Alice.

|

Despite its success, the RAYC closed in the early 1990s. The reasons were mixed and complex, but most had to do with a lack of funding and leadership and a city deeply hurt by the decline of the oil and gas industry that began to affect residents in the 1980s. Many Mexican-American youth had no choice but to leave Alice in search of better employment possibilities elsewhere.

However, the RAYC history as a community center for barrio youth should not be forgotten. As noted earlier, no other Mennonite program in the region enjoyed its success and longevity. Most – including the maternity clinic and kindergarten program – had closed by the late 1960s as VS programs began to shut down their units in the area.

The history of the RAYC provides a snapshot, a portrait of sorts, of Mennonites in a context away from the rural Midwest and urban areas where historians have focused most of their attention.22 Since the 1960s, Mexican Americans from South Texas have contributed much to the Mennonite church in the form of pastoral leadership, social activism and community organizing. As the membership of Latina/o Mennonites continues to grow, in both rural and urban contexts, it has become more important than ever to acknowledge the long and engaged history of Latina/o Mennonites. Acknowledging the significance of the Rancho Alegre Youth Center and what it tells us about Mennonite social engagement in South Texas is a small move in that direction.

1. Antero Rodriguez, “Of The Brown Seed,” The EMC Bulletin Vol. LVI, No. 4 (August 1977), 4. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

2. Paul S. Taylor, An American-Mexican Frontier: Nueces County, Texas (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1934).

3. Alicia Salinas, “ALICE, TX,” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hea01), accessed March 19, 2011. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

4. Texas Almanac: City Population History, 1850-2000, www.texasalmanac.com/population.

5. Alicia Salinas, “ALICE, TX,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Felipe Hinojosa, “Making Noise Among the Quiet in the Land: Mexican American and Puerto Rican Ethno-Religious Identity in the Mennonite Church, 1932-1982,” Ph.D. diss., (University of Houston, 2009).

7. “The Conference Messenger,” June 1968, 1; “History of the Alice Mennonite Church,” Bulletin from Church dedication, March 21, 1965. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

8. “Mennonite Church Dedication Set Today,” Alice Echo-News, March 21, 1965. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

9. Dan and Mary Miller, interview with author, August 30, 2010, Boerne, TX., digital recording.

10. Dan Miller, Paper presented at the Lion’s Club, August 10, 1972. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

11. The Civil Rights Status of Spanish-Speaking Americans in Kleberg, Nueces, and San Patricio Counties, Texas.” Accessed at Texas A&M University, Kingsville. Texas State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights, July 1967.

12. For a good analysis of the power of space see: Paul Christopher Johnson, Secrets, Gossip, and Gods: The Transformation of Brazilian Candomblé (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

13. Dan and Mary Miller, interview with author, August 30, 2010, Boerne, TX., digital recording.

14. Dan and Mary Miller, interview with author, August 30, 2010, Boerne, TX., digital recording.

15. For more on the experiences of African American and Latina/o Mennonites, See: Tobin Miller Shearer, Daily Demonstrators (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010); Felipe Hinojosa, “Making Noise Among the Quiet in the Land.”

16. Dan Miller, draft of letter for Methodist Newsletter, August 9, 1972. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

17. Lisa Guedea Carreño, interview with author, email correspondence, March 21, 2011.

18. Ibid.

19. Mathis Schools & Labor Camps, Orange Grove, Sandia Schools,” April 11, 1948. File 21.8, Dr. Hector P. Garcia Collection, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi; “Discrimination Suit Against Mathis Ended,” Corpus Christi Caller Times, May 4, 1957. File 21.8, Dr. Hector P. Garcia Collection, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi.

20. “Rancho Alegre Center Offers Introductions,” Alice Echo-News, March 24, 1985, 1. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

21. Armando P. Ibañez, “Rancho Alegre center keeping youths busy” Alice-Echo News, 1984. Accessed through personal archive of Dan and Mary Miller, Boerne, Texas, August 30, 2010.

22. Aside from works by Rafael Falcón, Graybill and Ortiz, most Mennonite historians have not engaged the Latino/a Mennonite experience. See, Rafael Falcón, The Hispanic Mennonite Church in North America, 1932-1982 (Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press), 1986; José Ortiz and David Graybill, Reflections of an Hispanic Mennonite (Intercourse, PA: Good Books), 1989.