Fig. 1

Nathaniel Yoder is a December 2010 graduate of Bethel College, with majors in music and Bible and religion with a minor in peace justice and conflict studies. Originally from Kalona, Iowa, he now lives in North Newton, where he is a part-time student at Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary-Great Plains and a painting contractor.

I. An Introduction

The Mennonite Church has been actively processing a number of conflicts and is asking what resources its members need to help congregations to process disagreements together. While this is part of our contemporary context, the awareness that there have been, and will continue to be, difficult issues to work through within the Mennonite denomination is not a new thing.

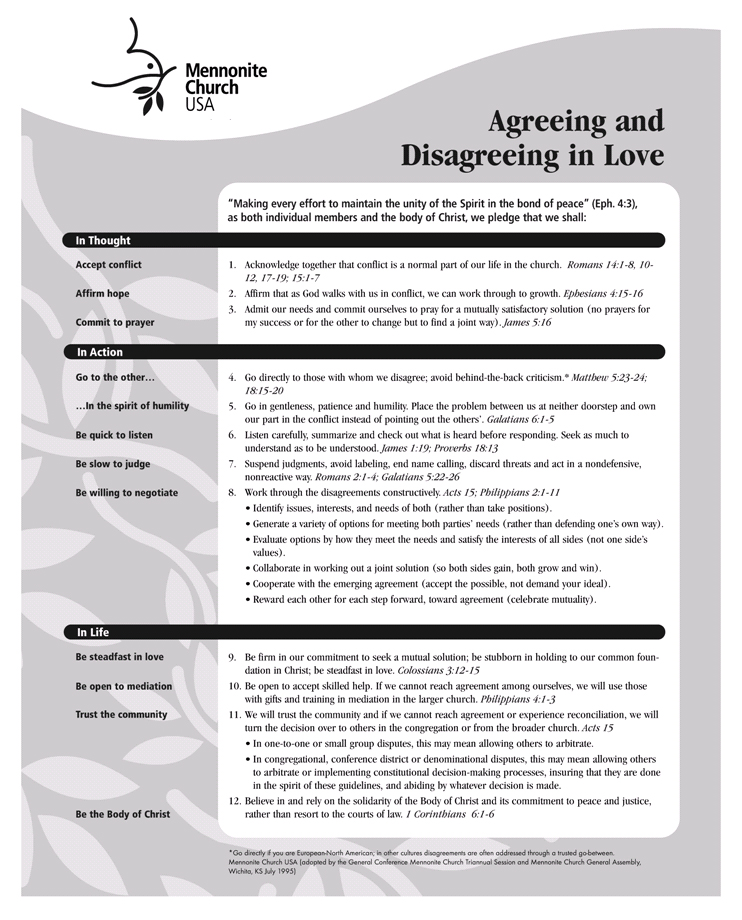

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love is a church document that may have some answers for these times of conflict. The document’s goal is to shed light on ways in which Mennonite congregations can process conflict constructively while maintaining healthy relationships.

The intent of this paper is to introduce Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love, analyze its theology as a modern application of Matthew 18:15-20 and use two case studies to evaluate the usefulness of its principles and study their merit in application.

By way of introduction, Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love (ADIL) is a prescriptive document, affirmed by Mennonite Church USA (MC USA), that suggests a way the Mennonite Church should be in conflict. Its self-stated purpose is to outline “approaches to conflict that will help us live out our calling to be Christian peacemakers.”1 It was created when “[Richard Blackburn], along with other members of the Peace and Justice Committee of the Mennonite Church, began to explore how the denomination could take the lead in helping congregations institutionalize healthy procedures so that conflicts might be handled at lower levels of intensity and not escalate destructively.”2 The result was a document drafted for and “[a]pproved by Mennonite Church and General Conference Mennonite Church July 29, 1995.”3

This was part of a momentous occasion in the life of the Mennonite denomination as a whole. “At the 1995 joint sessions of the MC [Mennonite Church] and GCMC [General Conference Mennonite Church] in Wichita [Kansas], the two conferences voted in favor of a formal merger, setting 1999 as their target date for complete denominational integration.”4 The Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective was also affirmed at the Wichita General Assembly. Affirmations and decisions made by both delegate bodies in 1995 have proved to be unifying, binding and, needless to say, of great importance to the Mennonite denomination.

The document itself is rather simple in design.5 It is a pledge organized into three main categories: Thought, Action and Life. Each category has several sub-points, both in simple and detailed form, through which it suggests how individuals and congregations ought to proceed in conflict situations. The detailed version of each sub-point is accompanied by one or more Scripture passages linked to either its text or theological basis. The second page of the document contains more explanation of the document’s biblical foundation, some basic ways a congregation might make use of the document, cautions and contact information.

ADIL is by no means an island. Other denominations have published and affirmed statements about how Christians should relate to one another in conflict situations. Many of the principles and ideas found in ADIL are seen in these other documents as well.6 The overall structure of ADIL, however, seems to be unique.

II. Theological Considerations

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love may be seen as a modern application of Matthew 18:15-20, a passage Mennonites have looked to for practical direction in times of conflict. The Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective references Matthew 18 in four places and uses it as the main scripture for the article on “Discipline in the Church.”7 The Central District Conference’s (CDC) Working Statement on CDC Polity from 1995 “models a Matthew 18 approach to solving disputes.”8

This usage, however, did not occur in a vacuum. The Mennonite Church and General Conference Mennonite Church jointly asserted in 1983 that “[t]he church has long found the ‘rule of Christ’ in Matthew 18:15-22 to be a practical, though demanding, process for establishing consensus and restoring fellowship among believers.”9 John Paul Lederach, Distinguished Faculty at Eastern Mennonite University, has argued that these verses “give direct and practical teaching from Jesus. They provide specific guidelines for how we are to proceed when we feel we have been wronged or when we feel that a sister or brother has erred.”10 More recently, Matthew 18 served as the guiding biblical passage for “How to Resolve Interpersonal Conflict” in The Mennonite Handbook.11

Clearly, Matthew 18 is a significant text for Mennonites. The structure and flow of ADIL parallels Matthew 18:15-20 in three ways: it outlines a specific method for engaging conflicts; emphasizes reconciliation; and affirms God’s presence and activity amidst conflict.

Matthew 18:15-20 outlines a specific method by which a Christian should address another Christian in times of conflict:

If another member of the church sins against you, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you, you have regained that one. But if you are not listened to, take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If the member refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if the offender refuses to listen even to the church, let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax-collector. Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you, if two of you agree on earth about anything you ask, it will be done for you by my Father in heaven. For where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them.12

As Colin Patterson puts it, “Jesus gave a ‘grievance procedure’ for individuals to follow.”13 In this passage, Jesus advocated a conversational process that begins between those people who are immediately aware of the offense. “It poses a series of important dual tasks. We must encounter both ourselves and others. We must recognize our fears and yet not be bound by them. We must define ourselves and also acknowledge the experience of others.”14

If this method of reconciliation proves ineffective, the next step is to work in a small group. The original people may still be in control of the situation and attempt to work out the difference together, but they are now aided by the presence of one or more other individuals. It is also possible that this step finds the control of the conversation in the hands of the added “witnesses.” In this case the additional person(s) in the conversation would act as mediator(s).

On the practical side, this step concerns the development of capacities and skills that help to create a safe space for people to be transparent and interact with each other. [...] This carries us beyond “reaching an agreement and resolving issues.” It leads us to deeper understanding and growth as individuals and communities.15

If this also proves unfruitful, then the suggestion is made to go to the larger church body for help. All that changes in this step is “the number of people involved.”16 Blackburn and Brubaker state the progression as follows:

The process emphasizes three primary steps: Go to the other in a spirit of humility and seek negotiation through direct dialogue; Bring in “one or two others” to serve as neutral parties who help the disputants listen to one another and help them come to their own mediated agreement. Submit to the wisdom of the church, perhaps by allowing neutral parties from the conference or other judicatory structures to serve as arbitrators.17

The same progression outlined in Matthew 18 can be seen in ADIL with nearly identical wording. “Go to the other in the spirit of humility […] be open to mediation […] we will trust the community and if we cannot reach agreement or experience reconciliation, we will turn the decision over to others in the congregation or from the broader church.”18

Matthew 18’s emphasizes reconciliation as opposed to judgment. The key word is “regained,” or “won” in other translations. John Howard Yoder argues that “[t]he intention is restorative, not punitive.”19 “Regained” is a stand-in for “reconciled,” and the purpose of the confrontation is to bring those involved into right relationship. This can be understood in a one-on-one context; however, it would be easy to misconstrue the portion of text immediately following as prescribing a more dogmatic and judgmental role to the church. John P. Meier argued that verse 17 should be understood in such a way. “If the sinner rejects the judgment of the full assembly of believers, he is excommunicated.”20 Likewise, Robert H. Gundry asserts that the Matthew 18:15-17 text “as a whole carries the meaning of ostracism.”21

This is not the case. Yoder reiterates the concept of restoration as paramount: “The intention is not to protect the church’s reputation or to teach onlookers the seriousness of sin, but only to serve the offender’s own well-being by restoring her or him to the community.”22 After all, he argues, doesn’t the Lord’s Prayer say “forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us”? In addition, Jesus gives the command, in the event that these three steps have failed, to “let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax-collector.”23 Based on the habits of Jesus recorded in the gospels, Lederach interprets the text to mean “Eat with them!”24 Distance and avoidance are not options. Rather, we ought to strive to both “define ourselves and still maintain appropriate emotional contact and relationship with those who differ from us…”25 Francis Wright Beare is also convinced that verse 17 should be seen in light of Jesus’ interactions with Gentiles and tax collectors.26 With this in mind, the requirement of restoration and reconciliation, as opposed to punishment, is clear.

Likewise, ADIL goals are restoration and the maintenance of relationships. It suggests an attitude of honesty and a commitment to mutuality. Achieved mutuality is restoration. Arguably, the title itself makes the clearest statement of intention. We are to go about our differences in a loving manner. This process values healthy relationships and restorative process over teaching lessons and punishment.

A large part of ADIL is drawn from our understanding of modern mediation and conflict resolution processes, to which Yoder argues Matthew 18 is akin:

We have here a fundamental anthropological insight into the relationship of conflict and solidarity. To be human is to have differences; to be human wholesomely is to process those differences, not by building up conflicting power claims but by reconciling dialogue. Conflict is socially useful; it forces us to attend to new data from new perspectives. It is useful in interpersonal process; by processing conflict, one learns skills, awareness, trust, and hope. Conflict is useful in intrapersonal dynamics, protecting our concern about guilt and acceptance from being directed inwardly only to our own feelings. The therapy for guilt is forgiveness; the source of self-esteem is another person who takes seriously my restoration to community.27

The restorative message of Matthew 18 emphasizes that reconciliation holds the utmost importance in situations of conflict. That is not to say that reconciliation means all parties must be in agreement – rather, having reconciliation as the goal informs us that the process by which we work through our differences is much more important than the outcomes of our deliberations. “The way churches make decisions is as important as what decisions are made.”28

Most importantly, Matthew 18 makes the claim that God is present and active in our conflict. Verses 18 and 19 suggest that Christians act on behalf of God in conflict situations. “The church … has the authority to pronounce judgment in God’s name, and the church has the authority to release persons from that judgment and restore them to fellowship.”29 If Christians take this seriously, the meaning of our actions in times of offense are much weightier than we might normally consider them. How we are in conflict becomes more important than what the conflict is about. Instead, Christians, even Mennonite Christians, have often understood this as the authority to ban, shun and excommunicate. Verse 20 assures that God is present when Christians are gathered, but Gardner suggests that our understanding of the church’s authority is clarified in verses 19 and 20 as well. As he sees it, “the community which God affirms in its binding and loosing exhibits several characteristics: (1) It assembles in Christ’s name. (2) It seeks the will of God in prayer. (3) It acts in agreement or consensus.”30 Again, the emphasis moves from deliberation and decision-making to how we are interacting, and to the process.

To be human is to be in conflict, to offend and to be offended. To be human in the light of the gospel is to face conflict in redemptive dialogue. When we do that, it is God who does it. When we do that, we demonstrate that to process conflict is not merely a palliative strategy for tolerable survival or psychic hygiene, but a mode of truth-finding and community-binding.31

ADIL takes this idea seriously. In fact, the first three points of the document are dedicated to this understanding. Beginning with the understanding that conflict is normal, ADIL claims that God is present in our conflict. ADIL affirms our ability to grow and find truth, through disagreement, all the while holding together the church community in mutuality. If there is to be a solution, it will be a “joint way.”32 ADIL urges us to relate in ways that keep in mind the claim of Matthew 18; we act on behalf of God.

ADIL parallels the structure of Matthew 18:15-20 and Scripture’s call to restore and reconcile. Finally, we are to enter into conflict with the knowledge of the presence of God and the understanding that we act on God’s behalf. These concepts are the foundational theological statements on which ADIL, as a document and a method, is built.

III. Case Studies: Does it work?

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love suggests a particular way of working through conflict among Christians. To that I asked a simple question: Does this work? I conducted a survey of two congregations in order to evaluate the usefulness of this document’s principles and study their merit in application. I will describe the size, makeup and process of each of the two congregational groups and then look at the results of their respective surveys. This will include the results for the individual groups, their averages and outliers, as well as a comparison of the two surveyed bodies to one another and to Matthew 18.

A. Developing the Survey

To develop a survey that would be useful for evaluating ADIL, I needed to allow for various levels of knowledge and disclosure and be able to evaluate more than one moment in time. As was confirmed by my research, not many people are familiar with ADIL. I used rephrased versions of ADIL’s main points as items within the survey to allow individuals who knew nothing about the document to evaluate it as if they knew it well.

My method was to begin with the declarations as they stood in ADIL and then modify specific aspects of each in order to create understandable items. These items needed to be functional at all levels of self- and community disclosure. To make this possible, I chose to operate on the seven-point Likert scale, seen below, for the majority of the items:

1–Strongly Disagree

2–Disagree

3–Disagree Somewhat

4–Neutral

5–Agree Somewhat

6–Agree

7–Strongly Agree33

This allowed interviewees to answer without any explanation at all. At the same time, some people wished to answer in detail. To ensure this possibility, I allowed space for explanation if the interviewee was interested in elaborating on his/her answer.

Finally, it was essential that the survey also have a component of time or it would have been simply a snapshot and not a useful comparison or evaluation tool. To account for this, I needed both a past and present/future viewpoint from which to evaluate several of the survey items. I used the entry point of outside help (in the form of conflict resource professionals) as the line between past and present/future. This was incorporated into the survey by having each individual evaluate each of these items twice – first while thinking about the time before their interaction with conflict resource professionals, and second while thinking about the time during and after said interaction. This had a second evaluative benefit because it allowed the interviewee to voice opinions and concerns related to the use of conflict resource professionals within the congregational setting (which is promoted by ADIL).

To create the survey itself, I sifted through the principles of ADIL and used them as an outline for the survey items. Each tenet of the document was altered into a statement with which the interviewee could either agree or disagree along the seven-point scale. I also consulted with several people for guidance in interpreting the principles of ADIL and applying them to the survey: David Boshart, pastor at West Union Mennonite Church, Parnell, Iowa; George O’Reilly, interim pastor at Wellman (Iowa) Mennonite Church; Gordon Scoville, interim pastor at First Mennonite Church, Newton, Kan.; John Yoder-Schrock, co-pastor at West Zion Mennonite Church, Moundridge, Kan.; Robert Yutzy, KIPCOR (Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution) coordinator for congregational ministries; and Kirsten Zerger, KIPCOR director of education and training. Their help and consultation was invaluable.

Some of the alterations were simply to help the interviewee understand how the statement applied to his/her situation. For example, moving from “Acknowledge together that conflict is a normal part of our life in the church” to “It was understood that conflict is a normal part of church life” was not a difficult leap. Other alterations, however, had larger theological implications. This is where consultation became imperative.

For example, I took great care in my alterations of the ninth point of ADIL: “Be firm in our commitment to seek a mutual solution; be stubborn in holding to our common foundation in Christ; be steadfast in love. Colossians 3:12-15.”34 This tenet contains, in its latter half, the only usage of the word “love” outside the document’s title. The title Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love suggests that the most important word is love and therefore it carries an incredible amount of weight in both meaning and interpretation. The concept of seeking mutually beneficial solutions is present within ADIL multiple times. I consolidated that presence into a single survey item. I then turned my concentration to the phrases “be stubborn in holding to our common foundation in Christ” and “be steadfast in love” because they are difficult to define and more difficult to use for evaluating the actions of others.

To begin with, there was consensus among those I consulted that this is the focal point of the document as a whole. This is where the most difficult and important meaning lies. In fact, Boshart claimed: “If we don’t hold being steadfast in love to this foundation in Christ, we’ve undone the genius of this document.”35 The conversations I had concerning the interpretation of ADIL were insightful.

The included Scripture reference for the ninth point is intended to give the reader context:

As God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience. Bear with one another and, if anyone has a complaint against another, forgive each other; just as the Lord has forgiven you, so you must also forgive. Above all, clothe yourselves with love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony. And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were called in the one body. And be thankful.36

In reference to this passage, Scoville said: “It doesn’t get you out of the paradox, but it is a helpful. If you look at love in its context in the New Testament, love is how you engage the topic not how you avoid it.”37 O’Reilly conveyed a more intense image:

You see we’re ready to forgive discourtesy, maybe thoughtlessness, maybe speaking without thinking. Are we ready to forgive real things? I mean actually when someone meant to injure me, in the mind of others, actually did damage my reputation, purposefully […] Often in church conflict we want to love people in a reasonable way. […] What’s reasonable about what God has done? […] This is where you need people to not only intellectually understand it, but you need them to feel the bite of it.38

To be steadfast in love needs to be informed, and maybe theologically informed, but it needs to be a theology not of just the mind but also of the emotion. What does it mean to ‘forgive others as God in Christ has forgiven me?’

Boshart and Scoville also brought to the table an evaluation of love as an argument ending claim. It is possible for persons to be in disagreement and for one to accuse the other of not loving as a way to maintain power. Both made clear they reject this notion. Like O’Reilly, they do not see the use of love to control a conflict situation as a possibility.

For the survey, I needed to make statements that contained an action verb to make it easier for the interviewee to evaluate the group on a scale. Yoder-Schrock helped me evaluate the verbs I chose when reframing the statements from ADIL. In our conversation, he asked if the verbs were too passive and if they would fail to provide an understandable mental image to connect with their respective statements. He also asked if the verbs leaned too far toward the active side, which might make interviewees disproportionately less likely to affirm the presence of a particular principle from ADIL.39 I changed the phrase “be stubborn in holding” to “persons appealed.” Being stubborn implies taking a stance and that is precisely what one must do when actively seeking a sympathetic response. Secondly, I chose the verb “remained” to replace “be steadfast” because “remaining” has a steady, foundational quality to it.

Defining “love,” however, was the most difficult task. My conversations hinted at several definitions, often expanding the envelope rather than narrowing the focus. This was a necessary process to develop my own understanding of how the word “love” should function in ADIL. Boshart and Yutzy were instrumental in coming up with a small word set to communicate meaning while allowing interviewees the opportunity to evaluate.

Boshart maintained that the balance and paradox set up in the person of Jesus Christ in John 1:14 is immediately applicable. “I think if we are going to hold to our common foundation in Jesus Christ, we need to strive for 100 percent grace and 100 percent truth. And sometimes, my feeling is the interpretation of being steadfast in love is to be full of grace and forget about truth, and that’s where I get concerned.”40 Since “the Word,” taken as Jesus Christ, was “full of grace and truth,” arguably 100 percent grace and 100 percent truth, it should be our example when we attempt to understand what love might look in the context of conflict.

The words “patient” and “kind” immediately resonate with the list from I Corinthians 13. Yutzy asserted that this passage is not about marital love so much as the love between disagreeing parties. The “love chapter” is sandwiched between two chapters concerning the disagreements within the congregation and the conflict that has arisen. Chapter 13 is written for the congregation at odds.41 The final statements read: “Persons appealed to the congregation's commonality in Jesus Christ. Persons remained patient, kind, truthful and gracious.”42

Through this process, I was able to alter the principles of ADIL into survey items. The intent was to have each participant evaluate the entire group involved and not simply him/herself. The completed surveys would, in turn, give me a glimpse of how the principles ADIL operated within the given case study. Neither case study group made explicit use of ADIL during the time spent processing conflict. This initially seemed to be to my detriment, but I discovered that it was quite the opposite. The absence of ADIL within each conflict situation allowed me the opportunity to get a more balanced representation of how familiar Mennonites are with ADIL. Had it been used in either situation, any study of familiarity with the document would have been less meaningful.

There are a few things I had hoped to include in my survey process, but was unable to include. One very important one was a congregation currently processing a conflict, which would have given me access to the feelings and ideas of people in the midst of a process. The reflections would have been about current events rather than memories of past events. This would have also allowed me to witness firsthand if a transformation of the conflict could have been seen during the presence of conflict resource professionals.

A second hope that was not realized was to survey a congregation that had experienced a failed conflict process. The information available from such a congregation would have been vital in testing the principles of ADIL. Was the absence of a principle of ADIL detrimental to the congregation? Which principles seem to be vital that were missing? These questions would have deepened my understanding of how the principles of ADIL function, or do not function, within a congregation.

Lastly, I would very much like to conduct a similar interview process in a congregation that made explicit use of ADIL as the foundational document from which it built its process. In this case, I would be able to speak directly about ADIL in my evaluation, how it was used and how it seemed to help or hinder. I would not be bound by speaking about the “principles of ADIL,” but rather could engage the document directly.

B. Surveying Congregations: Congregation A

Congregation A used a conflict resource professional as an entire congregation when processing a request by a convicted sex offender against children for permission to attend the church. Congregation A invited the conflict resource professional to lead a series of open congregational meetings. Congregational leadership, affirmed by the congregation, made this decision when it became clear the initial steps taken to resolve the issue had not succeeded.

It is important to note there was a process prior to the involvement of a mediator. The process moved from the offender, the spouse of the offender and the pastor to the congregation, and it attempted to keep reconciliation at its center. The move to the congregational level was made quickly because it was immediately understood this was a congregational issue that involved everyone.

The pastor held a face-to-face meeting with the offender and the offender’s spouse soon after they began attending. Knowing this issue would involve the entire congregation, leadership shared it with the congregation through small-group leaders. Next, leadership held an open meeting for the entire congregation, without the offender and spouse, and an accountability group was appointed for the offender. They held two more meetings, which included the offender and the offender’s spouse, and then suggested guidelines to the congregation. The guidelines did not meet the needs of the congregation and it was at this point that the congregation determined the need for outside assistance.

The conflict resource professional implemented a process with a four-month timeline, with the hopes that the congregation could reach consensus on a decision that would govern the current issue. The timeline was extended to the following summer for a process that lasted a total of 18 months.

Throughout this period, there were several kinds of meetings including various large groups and small groups. “We wanted a process with a wide variety of ways to plug in.”43 The conflict resource professional held a congregational meeting at the end of this process to determine the final decision. The goal was still consensus, but if it could not be reached after an hour of discussion and prayer a vote could approve a decision with an 80 percent majority.

“Consensus has not been reached … when any one member cannot live with the decision and believes that his reason for differing is a matter of principle.”44 Under this definition, Congregation A did reach a consensus, but at the end of the hour there were still people who were not completely comfortable with the proposed solution, so a vote was taken. The congregation’s attempt to get absolutely everyone on the same page had yielded a 97 percent consensus.45

I contacted the pastor of Congregation A and requested as wide a cross-section of potential interviewees as possible. The pastor graciously gave me the names and contact information for 60 individuals who were currently attending and had been attending the church during the conflict process. From this group, I was able to contact 56 individuals and to make arrangements for in-person, over-the-phone, or e-mail interviews with 33 individuals.

A vast majority of my interviews were done in person at a location that felt most comfortable for the participant. I had informed each participant that their identities would be held in confidence, but after a question I received from my first participant I changed my process slightly. The question was if anonymity meant I would not use the person’s name or that I would not quote anything that they had said. This prompted me to inform participants that I would not only hold their names in confidence, but would also ask their permission before directly quoting them. Upon this notification, participants became much more open and candid.

It should be noted that this group does not account for any people who would have left the congregation during or after the conflict process due to its outcome. Because of this, some dissenting voices are missing from my data. I do feel, however, that my data represents the congregation fairly. The 33 interviewees represented a fairly wide age range, were almost perfectly balanced according to gender and most certainly spanned a broad spectrum of opinions.

I had representation from opposite ends of the spectrum on several key issues. Opinions varied from highly positive to highly negative when reflecting on the process in general, its length, how well the congregation was able to carry out the process, the decision that was eventually made, how the congregants interacted inside and outside of process meetings and how helpful the conflict resource professional was. This variance makes me confident my results are a fair representation of Congregation A, its interaction with the principles of ADIL and its collective reflection on a time of overt conflict.

Congregation B

In Congregation B, a small, single-session, structured dialogue was used to help a group of seven people understand the perceived conflicts within the larger congregation. Some of these conflicts were centered on the pastor. This is not surprising because “most significant conflict in local churches is pastor focused.”46

Conflict resource professionals had already worked with the entire congregation at a basic level and had suggested the use of smaller dialogue groups. The conflict resource professionals, in consultation with church leadership, chose a group of individuals who would represent various facets of the congregation as it stood and bring a variety of opinions and points of view to the conversation.

These people submitted themselves to a structured dialogue process that required them to be active in listening and open to sharing. The conversation began at one point in the circle and always moved around the circle in order. Each person was required to listen in order to understand, never to interrupt and to write down any clarifying questions so they could be asked once the speaker was finished. The speaker was to share his/her feelings using “I” statements “without adding what others may or may not have felt.”47 They were not allowed to speak about individuals who were not present for the dialogue and could only speak directly to one another. They submitted to a strict process of listening and repeating back to the speaker what they had heard. However, there were only two guiding questions:

The leader of the structured dialogue was to maintain a safe environment, assist people in clarifying what they needed or were feeling and facilitate the process. This included opening and closing the conversation and guiding the participants through the process in its entirety.

The evening of the structured dialogue was not intended to reach an all-encompassing solution to the congregation’s current issues, but rather to foster meaningful conversation and push for mutual understanding.48

The pastor of the congregation graciously forwarded an e-mail concerning my project to all seven people who had participated in the structured dialogue. I received responses from four of the seven. I conducted four in-person interviews with the same explanation of confidentiality I used for Congregation A.

I asked these people to evaluate the group as a whole for each of the items on the survey. In this case, it was the correspondence of the results that ensured the quality of the survey. In a single-session dialogue, it would be quite simple to leave with a large variance in opinion as to how the group faired as a whole unless there was a high level of understanding by the end of the evening. This high level of understanding should then be reflected by congruence in the participants’ responses and reflections. I found this to be the case. To me, this says that not only was the process successful on a base level, but also that the four participants I interviewed probably have a decent understanding of the group as a whole.

Comparisons

Congregations A and B are both Mennonite congregations. Both interacted with and were guided by conflict resource professionals from KIPCOR. As previously stated, neither congregation made explicit use of ADIL within their processes. While there are these several broad and important similarities between the surveyed congregations, there are also many differences.

The first important difference to note is the sizes of the groups. The Congregation A case study consisted of 33 people from the context of a church-wide process while the Congregation B case study consisted of only four people out a possible total of seven. The Congregation B group was hand-picked from a larger congregation while the Congregation A group represented an attempt at finding a balanced and informative, but somewhat random, cross-section of the larger congregation.

Secondly, the congregations were involved in very different processes. Congregation A was involved in a decision-making process with a well-defined end goal. The end goals that Congregation B worked toward were successful implementation of process and the gaining of understanding. This difference in goals alters the congregations in important ways. Congregation B had a very open-ended goal that could be achieved whether the group came to an agreement or not, while Congregation A had to, in some sense of the word, come to an agreement on a very difficult issue. This put an added amount of pressure on Congregation A.

Thirdly, the length of the process was quite different. Congregation A was involved in a process that lasted 18 months while Congregation B met formally only once, for several hours. This means Congregation A was involved in a much more exhaustive process, both in terms of time and information. Congregation B, on the other hand, was involved in an intense discovery process designed to open up conversation channels and bring opinions and viewpoints to the surface, but not necessarily to resolve them. In this way, the time-frame and end-goals for each congregation are appropriately matched. Despite the differences between the surveyed groups, the proposed universal nature of ADIL suggests it is still valuable to compare them to one another because the same basic principles can and should be at work in both congregations.

C. Evaluation of Data

I have evaluated the data I collected in four important ways:

As a rule, I will first look at each of the surveyed congregations’ results individually and then compare them to one another.

Congregation A

To begin, I evaluated the principles of ADIL according to Congregation A. By compiling items 2 through 11, 14 and 15, for which participants recorded a change in the group’s behavior across the threshold of outside involvement with their respective opinions on that change, I was able to see how the group felt about the principles of ADIL.

For example, if a participant responded with a 2 in the “before” portion of item 6, a 7 in the “after” portion and related that change as positive, she would have effectively affirmed the 6th point of ADIL (“Listen carefully, summarize and check out what is heard before responding. Seek as much to understand as to be understood. James 1:19; Proverbs 18:13”):49

6. Persons listened carefully and sought to understand others as much as they sought to be understood.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?50

Secondly, it would be equally affirming of ADIL for her to say that the group made a move away from the ability to listen to one another and that this had a negative effect:

6. Persons listened carefully and sought to understand others as much as they sought to be understood.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?51

Thirdly, a response that does not record any perceived change in the Before/After responses may still affirm or deny the principles of ADIL. An unchanging response between 5 and 7 accompanied by a positive individual perception would be an affirmation. An unchanging response between 1 and 3 accompanied by a negative individual perception would also be an affirmation. A denial would consist of the opposite pairing for either combination:

6. Persons listened carefully and sought to understand others as much as they sought to be understood.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?52

This particular response would deny the principles of ADIL. Just as an unchanging response between 5 and 7 accompanied by a negative individual perception would be a denial of the principles of ADIL.

Congruence between the movement and the participant’s opinion of that movement constitutes an affirmation. A discontinuity constitutes a denial. There was the option to answer that the movement made by the group was neither positive nor negative and such an answer neither affirms nor denies ADIL.

For this portion, I received a total of 272 usable responses out of a possible 396. The 124 unusable responses were from those interviewees who did not provide data on how they personally perceived the congregation. This means they effectively provided no data concerning what they personally thought of a certain aspect of ADIL. A usable response consists of any two Before/After answers plus the participant’s own perceptions and opinions. Whether that response is an affirmation, denial or other is determined by the participant’s response to the corresponding opinion portion. Of the usable responses, I received 224 affirmations, two denials, 15 “neither,” three “both” and 28 no answers. This is an 82.4 percent affirmation of the principles of ADIL.

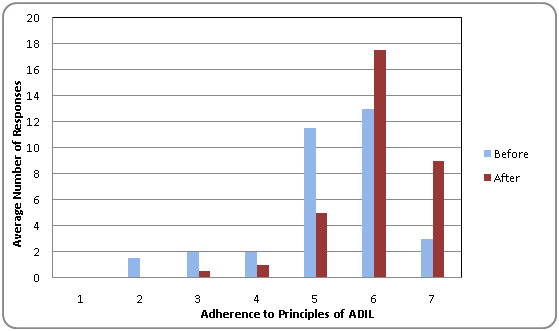

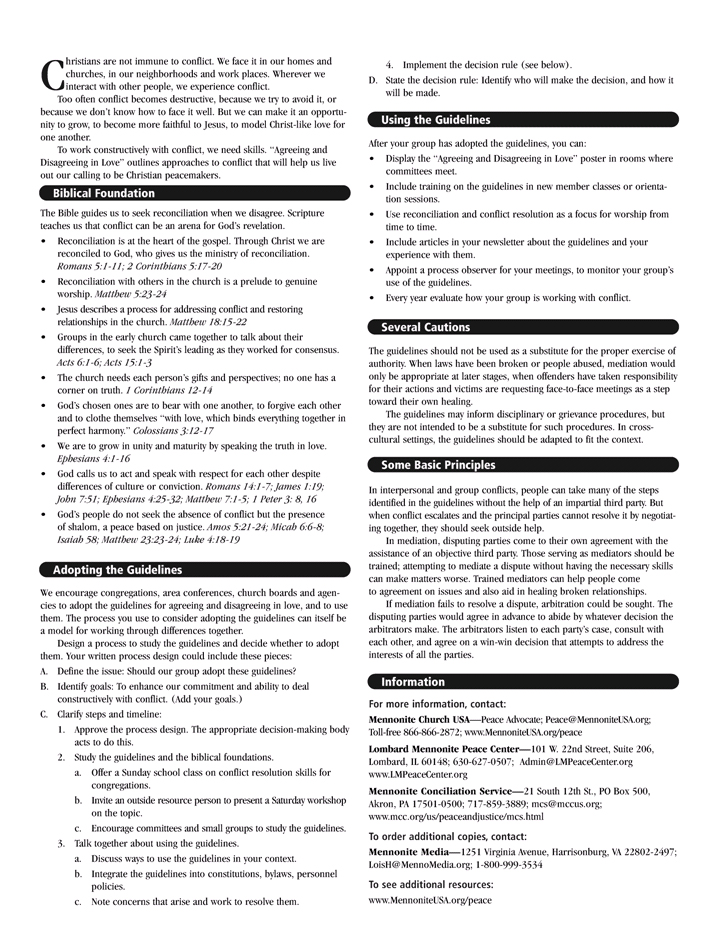

Secondly, Figure 1 shows Congregation A’s average scoring of itself on the 10 Before/After (items 2 through 11) items below:

2. It was understood that conflict is a normal part of church life.

3. Persons were committed to finding a win-win/mutually beneficial solution.

4. Persons engaged in direct interaction and face-to-face communication when disagreeing (as opposed to indirect/behind the back/triangulation).

5. Persons focused on, or “owned,” their own part in the conflict (as opposed to pointing out what others were doing/thinking that perpetuated the conflict).

6. Persons listened carefully and sought to understand others as much as they sought to be understood.

7. Persons were non-judgmental when interacting (there was no name-calling, labeling, threats or defensive behavior).

8. Persons were willing to negotiate and work through disagreements constructively.

9. Persons appealed to the congregation's commonality in Jesus Christ.

10. Persons remained patient, kind, truthful and gracious.

11. Persons were open to the help of conflict resource professionals.53

The purpose of this evaluation is to show the general movement of the congregation as it evaluated itself. The perceived movement was experienced while the conflict resource professional was present. These items were aimed at helping the group evaluate itself and the outside help it received, as well as the principles of ADIL. The seven-point Likert scale is represented on the x-axis and the number of interviewees is represented on the y-axis. The data represented is the average of all 10 Before responses in comparison with all 10 After responses.

Fig. 1

Notice that response categories 2 through 5 all decrease after outside help has been brought into the congregation and increase in both 6 and 7. A higher number on the Likert scale suggests greater adherence to the principles of ADIL. Items 2-11 on the survey were consciously worded to be congruent with ADIL to facilitate evaluation. The higher the response on the Likert scale, the more that individual perceived that the congregation enacted that particular statement, and therefore a principle of ADIL.

One can quickly see that there is distinct movement in the group’s self-evaluation that states greater adherence to the principles ADIL. It is even more important to remember that 82.4 percent of the participants felt that movement in the direction of greater adherence to the principles of ADIL was positive and/or beneficial to the congregation as a whole.

This also suggests that the step Congregation A took in hiring a professional to help them process their current conflict was indeed a step in the right direction. If the congregation views the principles of ADIL positively and the congregation’s adherence to them increased during the time they worked with a conflict resource professional, then it follows that outside help was beneficial.

More importantly, these data suggest that the principles of ADIL have the ability to change the aspect of congregational life related to managing differences for the better. Here is how: Congregation A, by and large, considers movement in the direction of greater adherence to ADIL as positive and beneficial to the group. The data show that, with help, Congregation A was able to increase its adherence to ADIL. Since the congregation felt better about its collective self, the principles of ADIL were beneficial to the congregation. Participants made mention of this with comments like “It [the congregational process] changed the way we perceive conflict” and “added experience for dealing with conflict.”54

Thirdly, there are some important themes that came up in the participants’ responses. This data is taken from all portions of the survey, especially items for which there was no Likert scale (items 12, 16, 21 and 22).55 One important theme was length. The length of the process was a concern to many of the participants. A majority of people related that the process took “too long.” They expressed comments akin to the following when speaking about the length of the process: “patience seemed to wane,” “wore people out,” “we were very tired,” “rather laborious” and “like going to the dentist.” Some felt a decision had been made well before the process was brought to an end; however, there were several individuals who strongly suggested that the process was either cut short or not followed closely enough when it came time to make a final decision.

One individual responded that the congregation moved in a negative direction near the end of the process and as a result this individual found the process to have failed. I include this as an example because, even though the data seem quite positive on average, it is important to represent the congregants’ variety of experiences. This same individual made a strong suggestion that the group should have learned to use the process “more effectively.” In fact, most of the negative responses I received were accompanied by a comment that a certain portion of the group did not abide by the process or use it effectively. This is important because it suggests a more careful use of the given process may have positively affected the group’s overall self-evaluation. Some said that process length could be shortened if members could “trust persons with experience.” They also related that a higher level of trust overall would have greatly benefited the process.56

Another important, and related, theme was relational strength. The vast majority of interviewees made one or more comments about the unity of the congregation and the strength of the relationships within the congregation. Many people felt this process allowed participants to be “more open” and to disagree with one another in such a way as to build stronger relationships within the church. These people related this aspect of the process as sometimes tiring, sometimes difficult, but profoundly meaningful and extremely hope-filled. They used words and phrases like “built trust,” “transparency,” “honest expression” and “gained some confidence.”

Congregation A had a fairly positive experience of conflict in that it proved to be a time of growth. They referenced it as a “learning experience,” that they “learned a lot about listening” and it had “made me a bit more sensitive to others.” This may be why one individual commented that “conflicts since have been handled sensitively and effectively.”57

Lastly, Congregation A moved very quickly from a smaller group to the entire congregation. It is my understanding that this move was made because it was understood early on that this conflict involved everyone in the congregation. One could argue that this progression does not fit the Matthew 18:15-20 model very well.

The progression of meetings, however, may suggest the opposite. The leadership attempted a decision-making process with a smaller group who attended the earlier set of congregational meetings, but it was ultimately rejected by the larger congregation. This could constitute a failure at the second step proposed in Matthew even though the meeting was open to the whole congregation.

It really depends on how we define the first congregational meetings. It can be said that Congregation A moved from involving smaller groups to adding more individuals. The first dialogue processes included only the offender, spouse and pastor. From this angle, the process appears to have followed the Matthew 18 prescription. A participant stated that “when [this issue] surfaced it was dealt with immediately.”58 This sort of sentiment is most certainly aligned with the concept of “going directly” which I have argued is present in Matthew as well as in ADIL.59 Overall, I would say the process at Congregation A had several parallels to the process in Matthew 18:15-20 with some deviations and variations.

Congregation B

First of all, Congregation B made a very strong statement about the principles of ADIL. Again, the survey items used for this evaluation were 2 through 11, 14 and 15. I received 48 usable responses out of a possible 48. All of the participants provided adequate information on their personal opinions and perspective as per the method I explained above. This means they all provided data concerning what they personally thought of the principles of ADIL. Of these responses, one neither affirmed nor denied ADIL and all 47 others affirmed it, for a 97.9 percent affirmation of the principles of ADIL.

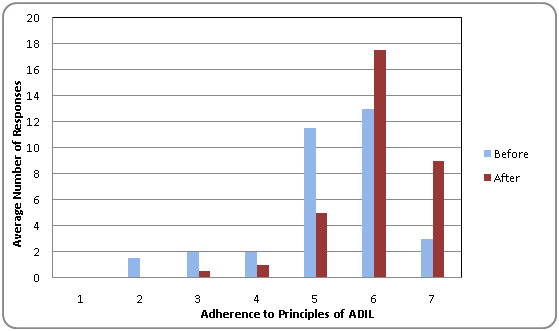

Secondly, Figure 2, in the same manner as Figure 1, shows Congregation B’s average scoring of itself on the 10 Before/After items (2 through 11). The purpose of this evaluation, again, is to show the general movement of the congregation as it rated itself. The movement was experienced as occurring while the conflict resource professional was present. For congregation B, this means the several hours spent in intense, structured dialogue.

Fig. 2

The increase in adherence to the principles of ADIL for Congregation B is quite obvious. None of the participants had any negative evaluations of the process. In fact, there were no responses that moved contrary to the principles of ADIL. Each respondent stated either that the group began in a positive position and remained there or that the group made a move in a positive direction. These data strongly suggest that the principles of ADIL were used (even though the document was not explicitly mentioned) and that their use had a positive effect on the group. They also suggest that the presence of a conflict resource professional was positive for the group. The resource person’s process allowed the group to more closely adhere to the principles of ADIL.

Thirdly, I find the comments of Congregation B fascinating because of their agreement about several issues. First, all of the respondents expressed that this process allowed them to learn more about themselves, those in the group, the congregation as a whole and about meaningful dialogue. It was a profound learning experience. Each of the participants mentioned the feelings that they had upon the close of the evening. They shared feelings of “openness,” hope, unity, “togetherness” and a “deeper connection” to the other participants in the structured dialogue. While the dialogue itself was an isolated event, several of the individuals mentioned that they felt a continuing ability to speak “more openly” to others from that particular group. Each participant mentioned that the group did not come to an agreement and they, in fact, were more “aware” of the things about which they disagreed. Coupled with these comments, however, were expressions of connection and unity within the group. They all felt that, despite the knowledge of more conflict among the group, they were able to bond and participate in “deeper relationships” than they had prior to the structured dialogue. Finally, each participant relayed a desire to see more people from their larger congregation participate in similar dialogues. There was a collective response that such dialogue processes could potentially open up a congregation to a broader view of its own differences and an ability to remain unified amidst those differences.60

Lastly, Matthew 18:15-20 suggests that processing conflicts in smaller groups is the ideal. The step-by-step process outlined in the passage systematically moves from a smaller to a larger number of persons involved. In the case of Congregation B, it seems that the benefit of a smaller group is confirmed. When describing various portions of the structured dialogue process, Congregation B representatives used words and phrases such as “definitely change my perspective,” “I’m more aware of others now,” “uncomfortable but necessary,” “changing,” “valuable,” “helpful,” “a gift,” “we actually voiced opinions,” “we were heard,” there was “accountability gained” and the hope that “each member of the church” could engage in such a dialogue.61 This sort of intense and transformative language suggests that a small dialogue group is able to accomplish profound and meaningful things, even in a short period of time. It strongly affirms the call of Matthew 18.

At the same time, this group is a microcosm of the larger congregation that had already been processing disagreements. It is my understanding that at the congregational level, the Matthew 18 process was not directly followed. It would be interesting to hear reflections from the larger congregation about this time of interaction with conflict resource professionals.

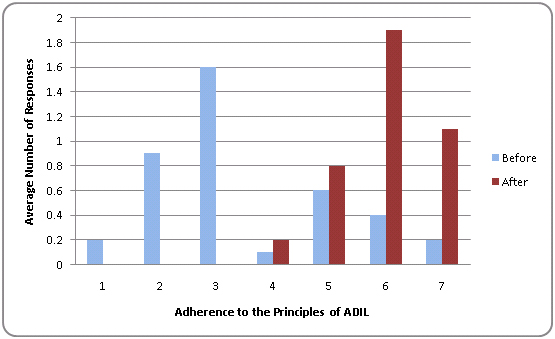

Comparison

A couple of important differences I see between the groups and the outcomes that each reported are size and goal. Simply put, the larger the group, the more difficult it will be to implement a process and have a uniform response. There is an advantage to dialogue processes in smaller groups because they ensure that everyone is heard and understood. As I have argued, this is the prescription of Matthew 18. If the group is much larger than seven or eight people, this quickly becomes difficult and cumbersome.62 The second difference is directly related to goals. When a group has the goal of understanding, as opposed to problem-solving, the task before them is less daunting and more manageable. Congregation A faced a decision-making process that, I would argue, contributed the most to its difficulties.

Both congregations were involved in what I would call a successful process. This is supported by the participants’ self-evaluation. Many of the participants from both groups related to me that they felt their respective congregations “handled the conflict well.”63 Along with this, both Congregations A and B reported a majority affirmation of the principles of ADIL and an increased adherence to the principles of ADIL during the time of interaction with a conflict resource professional. This suggests participants believe the principles in ADIL speak truth and contain useful ways to guide their respective congregations amidst conflict. It also suggests that adherence to the principles ADIL has the ability to change the congregation’s interactions in conflict situations for the better. This change seems to be directly connected to the entry point of a conflict resource professional. Therefore, help and guidance provided by conflict resource professionals is one factor able to move congregations in a positive direction. Participants from both congregations argue that the principles of ADIL need to be used more often and more effectively. Both cases speak quite positively about the principles of ADIL.

IV. Conclusion

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love is built, as a church document and a method, on Matthew 18:15-20. Matthew’s call to emphasize restoration and reconciliation can be seen throughout ADIL and both follow the same structure and flow. Both assert that we are to enter into conflict with the knowledge of the presence of God and the understanding that we are acting on God’s behalf. “Jesus’ sermon on Christian relationships (Matthew 18:15-20) is central to the Anabaptist understanding of appropriate relationships within the body of Christ.”64 Therefore, it is important that we recognize and celebrate the fact that this scripture passage can be so clearly seen in the Mennonite denomination’s conflict-guiding church document.

The principles of Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love do work, but congregations seem to be less able to use the more intricate aspects of the document without help. It seems the delegate body at Wichita 95 affirmed a document that has a wealth of opportunity for interpretation already contained within it. Research seems to show that the aid of trained people can help congregations more closely adhere to the principles ADIL. Research also suggests congregation members feel more positive about the process when the principles of ADIL are closely followed. While some of its prescriptions can be adhered to on a purely individual level, outside help is suggested and probably necessary to unpack and use some of ADIL’s more intricate aspects, especially in the context of a larger group.

Mennonites seem to be relatively unaware of ADIL beyond merely having heard of it. It was not referenced to the congregation in either of my case studies. Neither were the participants highly familiar with it. However, the techniques and strategies used by the involved professionals aligned themselves quite well with ADIL.

Might it, in this case, be possible for us to see ADIL as a figurehead document much like we view the Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective? It speaks truth and is certainly useful, but it is not something that just any individual can pick up and immediately know how to use or apply. Likewise, it is not absolutely necessary to be familiar with ADIL to enact its principles.

It is important to recognize that members of Mennonite Church USA worked to develop ADIL and the denomination has strongly affirmed it. This is a document by and for Mennonites just as the Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective is a document by and for Mennonites. If this is the case, then might we need to provide opportunities and make efforts to help each other understand and apply ADIL?

There are certainly multiple avenues through which this could occur. As one participant said, “There is never a final Amen to the process of ‘agreeing and disagreeing in love.’”65 We need to continuously strive to model the principles set forth by ADIL. Regardless of how we attempt this, it is important that we see this as a wakeup call and strive to be open to trying new ways of listening and talking to one another.

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love provides a Mennonite lens, based on Matthew 18:15-20, through which to view conflict with the hope of guiding disagreements in the personal and congregational setting. Its call is that of Scripture, that of the Jesus we see in Matthew’s gospel.

My research asserts that Mennonites believe this document speaks truth and contains useful ways to guide us amidst conflict, adherence to the principles ADIL has the ability to change congregational conflict for the better and it is imperative, in preparation for any and all conflicts of now and the future, the Mennonite church learns to hear the call of this church document.

1. Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Print. 2 (See Appendix A)

2. Swartley, Cheryl. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Conciliation Quarterly 16 No. 1 (Winter 1997): 2. Mennonite Central Committee. Mennonite Conciliation Service, 22 July 2008. Web. 4 Nov. 2010.

3. General Conference Mennonite Church 47th Triennial Sessions. Minutes. Rep. Newton, Kan.: Faith and Life, 1995. Print. 18.

4. Bender, Harold S., and Beulah Stauffer Hostetler. “Mennonite Church (MC).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 10 September 2010. http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/M46610ME.html.

5. Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Print. (See Appendix A)

6. Curtiss, Victoria G. Guidelines for Communal Discernment. Louisville, Ky.: Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), 2008. Print.

7. Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1995. Print. 55-58, 106.

8. Penner, Larry. “A Lesson from the Central District Conference on Homosexuality.” The Mennonite, 25 April 1995: 24. Print.

9. General Conference Mennonite Church and Mennonite Church. “Justice and the Christian Witness (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1983).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1983. Web. 05 November 2010. http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/M46610ME.html.

10. Lederach, John Paul. The Journey Toward Reconciliation. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1999. Print. 120.

11. The Mennonite Handbook. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2007. Print. 114-115.

12. Matthew. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print. 35 NT.

13. Patterson, Colin. How to Learn Through Conflict: A Handbook for Leaders in Local Churches. Cambridge: Grove, 2003. Print. 8.

14. Lederach, John Paul. The Journey Toward Reconciliation. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1999. Print. 127.

15. Ibid. 130.

16. Ibid. 131.

17. Blackburn, Richard, and David Brubaker. Making Peace with Conflict: Practical Skills for Conflict Transformation, ed. Carolyn Schrock-Shenk and Lawrence Ressler. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1999. Print. 171.

18. Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Print. 1. (See Appendix A)

19. Yoder, John Howard. Body Politics: Five Practices of the Christian Community Before the Watching World. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2001. Print. 3.

20. Meier, John P. Matthew. Wilmington, Del.: Glazier, 1983. Print. 205.

21. Gundry, Robert Horton. Matthew: A Commentary on His Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 1982. Print. 368.

22. Yoder, John Howard. Body Politics: Five Practices of the Christian Community Before the Watching World. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2001. Print. 3.

23. Matthew. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print. 35 NT.

24. Lederach, John Paul. The Journey Toward Reconciliation. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1999. Print. 134.

25. Ibid. 135.

26. Beare, Francis Wright. The Gospel According to Matthew : A Commentary. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1981. Print. 378-81.

27. Yoder, John Howard. Body Politics: Five Practices of the Christian Community Before the Watching World. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2001. Print. 10.

28. From the Editors. “Majority Rule?” The Christian Century. 16 June 2009: 7. Print.

29. Gardner, Richard B. Believers Church Bible Commentary: Matthew, ed. Elmer A. Martens and Howard H. Charles. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1991. Print. 282.

30. Ibid. 282.

31. Yoder, John Howard. Body Politics: Five Practices of the Christian Community Before the Watching World. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2001. Print. 13.

32. Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Print. 1. (See Appendix A)

33. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love Survey.” (See Appendix B)

34. Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Print. 1. (See Appendix A)

35. David Boshart, pastor, West Union Mennonite Church, Parnell, Iowa, personal interview, 8 June 2010.

36. Colossians. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print. 338 NT.

37. Gordon Scoville, interim pastor, First Mennonite Church, Newton, Kan., personal interview, 17 June 2010

38. George O’Reilly, intentional interim pastor, Wellman (Iowa) Mennonite Church, personal interview, 10 June 2010.

39. John Yoder-Schrock, co-pastor, West Zion Mennonite Church, Moundridge, Kan., personal interview, 19 June 2010.

40. David Boshart, pastor, West Union Mennonite Church, Parnell, Iowa, personal interview, 8 June 2010.

41. Robert Yutzy, Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution faculty, extensive personal interviews, April-July 2010.

42. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love Survey.” (See Appendix B)

43. Kirsten Zerger, Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution faculty, extensive personal interviews, April-November 2010.

44. Frykholm, Amy Johnson. “Out of Silence: The Practice of Congregational Discernment.” The Christian Century 3 April 2007: 34-38. Print. 36-37.

45. Kirsten Zerger, Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution faculty, extensive personal interviews, April-November 2010.

46. Leas, Speed B. Moving Your Church through Conflict. Washington, D.C.: Alban Institute, 2002. 99. Print.

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid.

49. Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Print. 1. (See Appendix A)

50. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love Survey.” (See Appendix B)

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid.

54. Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation A – Survey of 33 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: June-September 2010. Unpublished survey.

55. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love Survey.” (See Appendix B)

56. Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation A – Survey of 33 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: June-September 2010. Unpublished survey.

57. Ibid.

58. Ibid.

59. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love Survey.” (See Appendix B)

60. Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation B – Survey of 4 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: July-October 2010. Unpublished survey.

61. Ibid.

62. Kirsten Zerger, Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution faculty, extensive personal interviews, April-November 2010.

63. Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation A – Survey of 33 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: June-September 2010. Unpublished survey.

Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation B – Survey of 4 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: June-September 2010. Unpublished survey.

64. Ackley, Heather Ann. “Anabaptism and Pastoral Authority.” The Mennonite. 2 May 2006. Web. 1 Nov. 2010. <http://www.themennonite.org/issues/9-9/articles/Anabaptism__pastoral_authority>.

65. Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation A – Survey of 33 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: June-September 2010. Unpublished survey.

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love Survey:

1 – Strongly Disagree

2 – Disagree

3 – Disagree Somewhat

4 – Neutral

5 – Agree Somewhat

6 – Agree

7 – Strongly Agree

1. I am familiar with “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love” (which was affirmed by the Wichita 95 General Assembly and adopted by MC USA as guidelines for processing conflict).

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Each item has three parts. Evaluation before (the time prior to outside help being brought into the congregation) and after (the time from the moment outside help was brought in onward). The third part of the item asks for your own perception of the congregation. You may also add any comments at this point that help explain your answer. Please answer the questions as they apply to the group/congregation as a whole and not as they apply to you as an individual. In this particular conflict:

2. It was understood that conflict is a normal part of church life.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

3. Persons were committed to finding a win-win/mutually beneficial solution.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

4. Persons engaged in direct interaction and face-to-face communication when disagreeing (as opposed to indirect/behind the back/triangulation).

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

5. Persons focused on, or “owned,” their own part in the conflict (as opposed to pointing out what others were doing/thinking that perpetuated the conflict).

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

6. Persons listened carefully and sought to understand others as much as they sought to be understood.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

7. Persons were non-judgmental when interacting (there was no name-calling, labeling, threats or defensive behavior).

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

8. Persons were willing to negotiate and work through disagreements constructively.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

9. Persons appealed to the congregation's commonality in Jesus Christ.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

10. Persons remained patient, kind, truthful and gracious.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

11. Persons were open to the help of conflict resource professionals.

Before:1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

After: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this change as positive/negative/neither?

12. Did anyone/group utilize any conflict mapping strategies/exercises to help persons gain more perspective (give examples)?

If so, when? Did this happen prior to outside help being brought in? When did the outside help make use of these tools?

13. The mapping strategies/exercises benefited the entire group.

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Did you perceive this as positive/negative/neither?

14. Was the court system involved in this conflict?

Did you perceive this as positive/negative/neither?

15. Were any decisions arbitrated/made for the group?

Did you perceive this as positive/negative/neither?

16. Did this particular process change how the group handles disagreements?

Explain:

17. The congregation sought help at an appropriate time.

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Explanation if applicable:

18. The help that the congregation received was adequate/sufficient.

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Explanation if applicable:

19. The congregation should ask for help again if a situation arises.

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Explanation if applicable:

20. The congregation waited too long to seek help.

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

Explanation if applicable:

21. Describe how well/poorly you feel this conflict was handled by the church.

22. Are there other conflicts that the congregation has handled internally (without any outside help)?

Were they successful?

What process was involved?

David Boshart, pastor, West Union Mennonite Church, Parnell, Iowa, personal interview, 8 June 2010.

George O’Reilly, intentional interim pastor, Wellman (Iowa) Mennonite Church, personal interview, 10 June 2010.

Gordon Scoville, interim pastor, First Mennonite Church, Newton, Kan., personal interview, 17 June 2010.

John Yoder-Schrock, co-pastor, West Zion Mennonite Church, Moundridge, Kan., personal interview, 19 June 2010.

Robert Yutzy, Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution faculty, extensive personal interviews, April-July 2010.

Kirsten Zerger, Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution faculty, extensive personal interviews, April-November 2010.

Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation A - Survey of 33 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: June-September 2010. Unpublished survey.

Yoder, Nathaniel. “Congregation B – Survey of 4 Mennonites Concerning Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Undisclosed location: July-October 2010. Unpublished survey.

Ackley, Heather Ann. “Anabaptism and Pastoral Authority.” The Mennonite, 2 May 2006. Web. 1 Nov. 2010.

Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love. Wichita: Mennonite Church General Assembly, 1995. Mennonite Church USA. Web. 14 Feb. 2010.

Beare, Francis Wright. The Gospel According to Matthew: A Commentary. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1981. Print.

Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1995. Print.

Curtiss, Victoria G. Guidelines for Communal Discernment. Louisville, Ky.: Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), 2008. Print.

From the Editors. “Majority Rule?” The Christian Century, 16 June 2009: 7. Print.

Frykholm, Amy Johnson. “Out of Silence: The Practice of Congregational Discernment.” The Christian Century, 3 April 2007: 34-38. Print.

Gardner, Richard B. Believers Church Bible Commentary: Matthew, ed. Elmer A. Martens and Howard H. Charles. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1991. Print.

General Conference Mennonite Church and Mennonite Church. “Justice and the Christian Witness (General Conference Mennonite Church, Mennonite Church, 1983).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1983. Web. 05 November 2010. <http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/J8722.html>.

Groff, Anna. “Board Seeks Ways to Deal with Conflict.” Mennonite Weekly Review [Newton, KS] 1. March 2010. Mennonite Weekly Review: Online Edition. 17 March 2010. Web. 7 April 2010.

Gundry, Robert Horton. Matthew: A Commentary on His Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 1982. Print.

Leas, Speed B. Moving Your Church through Conflict. Washington, D.C.: Alban Institute, 2002. Print.

Lederach, John Paul. The Journey Toward Reconciliation. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1999. Print.

Matthew. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print.

Meier, John P. Matthew. Wilmington, Del.: Glazier, 1983. Print.

Patterson, Colin. How to Learn Through Conflict: A Handbook for Leaders in Local Churches. Cambridge: Grove, 2003. Print.

Penner, Larry. “A Lesson from the Central District Conference on Homosexuality.” The Mennonite, 25 April 1995: 24. Print.

Schrock-Shenk, Carolyn, and Lawrence Ressler. Making Peace with Conflict: Practical Skills for Conflict Transformation. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1999. Print.

Swartley, Cheryl. “Agreeing and Disagreeing in Love.” Conciliation Quarterly 16 No. 1 (Winter 1997): 2. Mennonite Central Committee. Mennonite Conciliation Service, 22 July 2008. Web. 4 Nov. 2010.

The Mennonite Handbook. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2007. Print.

Yoder, John Howard. Body Politics: Five Practices of the Christian Community Before the Watching World. Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 2001. Print.

Galindo, Israel. The Hidden Lives of Congregations: Understanding Congregational Dynamics. Herndon, Va.: Alban Institute, 2004. Print.

Halstead, Kenneth A. From Stuck to Unstuck: Overcoming Congregational Impasse. Bethesda, Md.: Alban Institute, 1998. Print.

Halverstadt, Hugh F. Managing Church Conflict. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster/John Knox, 1991. Print.

Lederach, John Paul. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1995. Print.

Smucker, Marcus G. Facing Difficult Issues: Dialogue and Discernment in Congregational Decisionmaking. 2003. Print.

Steinke, Peter L. How Your Church Family Works: Understanding Congregations as Emotional Systems. Washington, D.C.: Alban Institute, 1993. Print.

“The Discerning Community.” Pittsburgh Mennonite Church. 24 Jan. 2010. Web. 3 Sept. 2010. <http://pittsburghmennonite.org/2010/01/the-discerning-community/>.