Shearer, Tobin Miller. Daily Demonstrators: The Civil Rights Movement in Mennonite Homes and Sanctuaries. pp.1-17, 257-264. 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press. Reprinted with permission of The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tobin Miller Shearer is an assistant professor of history and the coordinator of the African-American Studies Program at the University of Montana. Prior to moving to Missoula, he worked for Mennonite Central Committee for 15 years in New Orleans, and Akron, Pa., and is the co-founder of the Damascus Road Anti-Racism Process.

It was thought best to have a separate [mission] work for the colored. –Merle W. Eshleman, white pastor, Philadelphia, 1936

The Reverend Rondo Horton understood white Mennonites. Since he began working for a Mennonite Brethren evangelist in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina in 1917, Horton moved in a religious community he would come to call his own. This ordained African- American minister and moderator of the North Carolina Mennonite Brethren Conference did not limit himself to one group of Mennonites. He thought of himself as “just a Mennonite.”1 Demonstrating his commitment to the broader Anabaptist community, Horton traveled to Chicago in 1959 and Atlanta in 1964 to participate in inter-Mennonite race relations conclaves. The official assembly photo shows Horton, dressed in a three-piece suit and a dapper necktie, sitting in the front row with Vincent Harding and Delton Franz, sponsors of the 1959 conference. His prominent position reflected his leadership role. Having observed white Mennonites evangelize African Americans, he knew that many of his coreligionists prided themselves on their racially egalitarian stance.2 He also knew that white evangelism of black people left the underlying problem untouched. So Horton challenged the gathered assembly to switch directions. “In working for better race relations,” he noted, “we begin at the wrong place. We should not begin working with the Negro. Mennonites should start working with the white people in the South.” Referring to the core Anabaptist values of discipleship and nonresistance, Horton concluded, “Teach them the way of love. Teach them that segregation is wrong.”3

|

Horton’s comments focused on southerners but also applied to Mennonites across the country. Interlacing their egalitarian record, a history of separation kept white Mennonites at a remove from their African-American co-believers. Horton knew this history firsthand. In the late nineteenth century a group of Mennonites known as the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren emigrated from Russia to the Midwest and on to the West Coast. Although they had been in the United States for far shorter a time than the African Americans they would soon work among, the Mennonites who first affirmed their religious faith in Horton’s home community nonetheless labeled their 1886 evangelistic endeavor to North Carolina a foreign mission.4 The local African-American community welcomed the Mennonite Brethren missionaries, who, despite intense opposition from the local white community, founded an orphanage for African-American children in the Blue Ridge Mountains. By 1925 the white evangelists switched from tending orphans to founding churches and developing local African-American leadership. Eleven churches emerged and eventually formed the North Carolina District of the Mennonite Brethren Church.5 Although separated by distance–most members of the Mennonite Brethren community remained west of the Mississippi–and by designation–the community was a foreign mission within the United States–the separation itself appears to have made the contact possible. Mennonite Brethren failed to start missions to African Americans in their home communities during this era. What was possible to do at a distance remained too controversial at home.

Separation also defined the interaction between African-American and white Mennonites in the early 1970s, long after Horton’s appeal had been forgotten. The Minority Ministries Council, a group of African-American and Latino Mennonites, met without white oversight and challenged racial subordination in the church. Although relatively short lived, lasting in official form from 1969 through 1974, the council nonetheless pushed African-American and white Mennonites into close contact through separation. Because council members had been able to separate, they stayed in the church. Members of the Minority Ministries Council talked frankly with their white co-believers in part because they could withdraw to their own organization after venturing into the white-dominated world. Here again, separation, although of a different kind than that employed by the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, allowed for a measure of interracial exchange. In this case, African-American and Latino Mennonite caucuses fostered scarce contact with white people amid the racial splintering of the late 1960s and early 1970s. If not for the Minority Ministries Council, many Mennonites of color would have left the church.

Mennonites, like most of their Christian cousins in the United States, thus embodied racial contradictions through much of the twentieth century. As Horton knew, white and African-American Mennonites first connected, ironically, through separation. Decades later, the practice continued. Only a religious group that was also a racialized community could engender such paradox. This chapter highlights the religiously motivated and racially conflicted history of separation and contact between African-American and white Mennonites between 1918 and 1971. Although this book focuses on the period from 1935 through 1971, the following overview of post-World War I Mennonite history provides important background to the study as a whole.6 As Horton’s ministry as “just a Mennonite” spanned more than half a century, so too does this historical overview. Through this summary, the paradox of separated contact serves to explain the complexity of motives and methods that made daily demonstrations possible.

Unlike the other tightly focused chapters of Daily Demonstrators, this chapter covers a broad swath of time to trace a theme of racialized separation. Although the history told here focuses on African-American and white Mennonites, it is not the only racial history of this quietist community. White Mennonites also came into contact with Latinos/as, Native Americans, and Asians. The work of historian Felipe Hinojosa on the Latino Mennonite community in South Texas and of sociologist Jeff Gingerich on Asian and other ethnic communities in Philadelphia tell important stories that fill out the history chronicled in this text.7 The ironies, contradictions, and continuities of exchanges between African-American and white Mennonites nonetheless offer critical insight. After a brief introduction to the Anabaptist roots of the Mennonite community, this chapter describes six periods in Mennonite race relations between African Americans and whites. The daily demonstrators described herein came from a religious community that found ways to connect across many racial lines despite and because of a desire to separate from the world.

The Mennonites Horton would grow to know so well arose out of the Radical Reformation in sixteenth-century Europe. Early Anabaptists argued that Martin Luther had not pushed his reforms far enough and challenged other reformers, like Ulrich Zwingli, to separate the church from state oversight. By 1525 a small group of believers in Zurich, Switzerland, had, in defiance of the local city council, met and rebaptized one another to demonstrate their belief. This emergent community of Anabaptists–literally, rebaptizers–put the authority of the scriptures before the authority of the state. Despite persecution, imprisonment, and execution by European state authorities, the movement continued to grow throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This free-church tradition eventually gave rise to the Hutterites, who followed their own path of communal living beginning in 1528; the Amish, who broke away from Mennonite groups in 1693 over matters of church discipline; and the Brethren, who merged Anabaptist and Pietist strands from 1708 forward. In the midst of this early diversity of religious practice among Anabaptists, the impulse to separate from one another and from the world remained strong.

The early Anabaptists articulated a set of core beliefs that shaped Mennonite doctrine. Menno Simons, an influential early church leader, left the Roman Catholic priesthood in 1536 to join the upstart movement that eventually bore his name. Simons and other early church leaders first articulated their belief in the primacy of the scriptures before all other authority. This belief, in turn, fostered a conviction against bearing arms that became known as the doctrine of nonresistance. In the area of church life, Mennonites promoted mutual accountability, known as discipleship, to encourage all community members to daily replicate the ethic of love modeled by Christ. Perhaps most important for this study, Swiss-South German Mennonites felt that they should separate themselves from society’s sinful influences, a belief that eventually became codified as the doctrine of nonconformity. As governmental officials persecuted those Mennonites who refused to bear arms or recognize the state’s authority, church leaders sought lands where they could practice their beliefs without interference from the world around them.

By 1683, one group of German Mennonites had settled in Germantown, Pennsylvania, where in 1708 they built the first Mennonite meetinghouse. Members of this community spread to the South and West during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as they sought new land and economic opportunities. Other groups of Mennonites, like the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren who would go on to proselytize Rondo Horton, came to the United States from Russia and settled in the Midwest and on the West Coast during the late nineteenth century. By the end of the twentieth century, nearly forty different groups of Mennonites populated North America, totaling nearly a quarter million members. As noted in the preface, I have focused on the two largest Mennonite denominations in the United States during the middle three decades of the twentieth century, the (Old) Mennonite Church and the General Conference Mennonite Church. In comparison to their religious cousins, both groups have had relatively greater involvement with African Americans. More strictly sectarian Mennonite groups, such as horse-and-buggy-driving Old Order Mennonites, had far fewer interactions across racial lines. As a result of a strong interest in service and evangelism to the poor and oppressed, (Old) and General Conference Mennonites moved outside communities defined by racial and theological homogeneity and encountered African Americans.

Attending to racial dynamics in the (Old) and General Conference communities, this project notes the particularities of each and yet contends that the racial experience of African Americans within both denominations was strikingly similar for the span of time under study here. (Old) Mennonites, especially in the large and wealthy Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Mennonite Conference, led the entire Mennonite community in ministry to African Americans by being the first Anabaptist group to baptize black converts into the church in 1897, when Robert and Mary Elizabeth Carter and their son Cloyd joined the Lauver Mennonite Church in Cocolamus, Pennsylvania.8 Members of that same regional conference body also started an industrial training and outreach mission to an impoverished African-American community in the Welsh Mountain area of New Holland, Pennsylvania, the following year. No similar activity took place among the General Conference Mennonites at this time, but African- American Mennonites testified that their experiences with Mennonites from the two denominations did not feel substantively different. Despite significant differences in how the two groups evangelized African Americans and separated themselves from the world, patterns of paternalism and prejudice proliferated in both communities. The brief historical outline that follows traces the history of both (Old) and General Conference Mennonites as they related to African Americans.

The Segregation Era, 1918-1943

The years 1918 to 1943 involved deliberate segregation, overt participation in the racial order, and initial resistance to change. Even as they sought to separate from the influences of a world they deemed sinful, (Old) and General Conference Mennonites followed that example of secular society by practicing racial segregation. From the end of World War I through 1943, African Americans like Rev. Rondo Horton would not have been welcome at most white Mennonite churches in the United States. Those who did venture into white congregations often found themselves shunted to one of the “colored missions” opened in this period. At Broad Street Mennonite Church in Harrisonburg, Virginia, and Pennsylvania mission churches in Lancaster, Philadelphia, Reading, and Steelton, (Old) Mennonite mission workers made deliberate decisions to segregate their urban mission efforts, usually after failed attempts at racial integration. For example, after holding integrated summer bible school classes “for a number of years,” church workers in Philadelphia reported in 1936 that “it was thought best to have a separate work for the colored.”9 During this time, General Conference Mennonites sponsored no organized missions to African-American communities. Such efforts would not occur until after World War II. As a result, the General Conference congregations remained racially homogenous owing to the restrictive housing covenants, sundown laws forbidding blacks to be out after sunset, discriminatory realty practices, and other overt methods that protected white communities from black infiltration during the segregation era. Throughout both Mennonite denominations, the initial welcome promised by early baptism of African-American believers in Pennsylvania dimmed as the realities of Jim Crow laws in the South and de facto segregation in the North confronted the Mennonite community.

During this period Mennonites drew their evangelistic techniques from external sources and also asserted that racial problems stemmed from the same. In the former instance, missionaries involved in interracial ministry were far more influenced by the methods and theology of evangelicalism than by Anabaptist credos.10 Having come relatively late to both domestic and foreign mission fields, Mennonites followed the example set by their more experienced white Protestant counterparts.11 Early Mennonite missionaries thus followed the lead of other evangelists who had set up separate stations for blacks and whites. Similarly, Mennonites from both denominations described racism as an issue external to the church community, an irony noted by the African-American Mennonites diverted to segregated churches.12 Mennonites, declared writers during the period, had only to avoid racial epithets and hatred to keep racism from entering their faith community.13 Although fewer than 150 African Americans had joined the church by 1943, these members quickly became aware that life on the inside of the church often did not match their leaders’ public claims of separation from the world’s sinful influence.14 In many instances, racially oppressive practices loomed even larger in the eyes of African- American converts because the church claimed to be separate from those practices.

Most white Mennonites in this period accepted the racial norms of their day in both the North and South. Despite articles in the church press cautioning against such action, overtly racist acts were relatively common. In the most dramatic case, the Virginia Conference acted to segregate receipt of sacraments by race in 1940. Three years later, Daniel Kauffman, the white Mennonite editor of the (Old) Mennonite Church national weekly, the Gospel Herald, drew upon eugenic thought when he warned his readers about the danger of “hordes of colored (and renegade white) races” overwhelming white Christians who used birth control.15 Through 1943, leaders of urban missions, bible school programs, and retirement communities maintained segregated mission sites. Although a few integrated groups managed to survive, racial segregation prevailed from Philadelphia to Sarasota. Even as Mennonite missionaries followed evangelistic methods and mores adopted from outside the church, they followed external patterns of racial segregation as well.16

A few Mennonites objected to such ready acquiescence to racial subordination by protesting segregation policies and advocating for the rights of African-American converts. In the early 1940s, white mission workers Ernest and Fannie Swartzentruber vehemently opposed the Virginia Conference’s segregation decision, a stance that eventually led to their dismissal. In 1943 another white mission worker, Sem Eby, advocated on behalf of an elderly African-American woman who had been denied access to a retirement community run by Mennonites in the village of Welsh Mountain, Pennsylvania.17 New African-American converts such as Roberta Webb and Rowena and James Lark carved out a space for themselves within the church through protest and social networking. Long-held Mennonite traditions of hospitality, concern for right relationship, and service to the poor and oppressed could also lead to egalitarian conduct. Values internal to the community did at times call believers to counter racial subordination, but the process was as fragile as it was rare.

Those who resisted and those who cooperated with racial segregation during this era seldom received enthusiastic support from mission boards. Most of the church’s missions had only begun to develop revenue streams before the Great Depression, and they struggled to survive through the 1930s. Responding to the economic instability of that decade, mission boards terminated assignments more often than they extended them.18 Nonetheless, the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities of the Lancaster Conference did manage to send four missionaries to eastern Africa in 1934.19 Here, as in the case of the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren who witnessed to a young Rondo Horton in North Carolina, evangelizing dark-skinned peoples at a distance drew significant attention and, in many cases, proved more successful than venturing across racial lines close to home. The same mission boards that managed to raise funds to send personnel across the Atlantic found it more challenging to raise funds in support of missions among African Americans in the United States. At the same time, mission boards seldom interfered with individually initiated efforts to minister to urban populations, migrant communities in the South, or rural communities in the Northeast.

From 1918 through 1943 church members set relational and institutional patterns that would confront African-American and white Mennonites for the next quarter century. White Mennonites from the (Old) and General Conference denominations consistently viewed African Americans during this time as sullied representatives of the world from which they sought to separate. Although a small group of evangelists reached across the color line in the (Old) Mennonite community, they brought with them the same paternalistic attitudes and assumptions of cultural superiority that defined much of white evangelistic contact across racial boundaries through World War II. In stark contrast, the Communist Party generated good will and no few allies within the Africa-American community because of its demonstrated commitment to ending racial discrimination and illusions of white superiority. Mennonites would take far longer than their communist adversaries to gain similar standing as they carried forward the legacy of segregation.

The Era of Evangelism, 1944-1949

During the next six years, Mennonites read reports about churches planted within African-American communities, listened to debates over the problem of how best to respond to racial diversity in the church, and peered at the spectacle made of new converts. Meanwhile, African Americans like Rondo Horton struggled to build a home for themselves within the Mennonite community. By the end of the 1940s, largely owing to stronger mission agencies and the energetic and visionary leadership of African-American Mennonites James and Rowena Lark, eight new African- American and racially integrated congregations appeared across the country.20 Although two new congregations were begun in Pennsylvania during this period, the center for this new growth and evangelism shifted from the East to the Midwest as the Larks founded Bethel Mennonite in Chicago in 1944; the following year James Lark became the first ordained African-American minister in the Mennonite church. The Larks generated interest across the church community in their mission efforts and by 1949 had brought forty-six new African-American converts to full church membership.21 In Ohio and Illinois, regional conference bodies expressed new interest in planting integrated churches, an effort that bore fruit in the founding of Lee Heights in Cleveland and Rockview in Youngstown in 1947. The Ninth Street Congregation in Saginaw, Michigan, founded two years later, also added to the shift westward.

Although the General Conference denomination did not show the same interest in church planting among African Americans at this time, individual white members ministered to impoverished African-American families in Gulfport, Mississippi, at the Camp Landon mission. After the Civilian Public Service unit in Gulfport closed at the end of World War II, Camp Landon administrators switched from constructing privies to conducting recreation programs, summer bible school sessions, and weekly sewing and woodworking classes for children. Although by the 1950s volunteers would work exclusively with African-American children, during this period the camp held separate programs and open houses for whites and blacks.22 Local Mennonite congregations supported the camp’s segregated mission and practiced a racial separation of their own. Members of Gulfhaven and Wayside did not at that time welcome African Americans into their fellowships.23 General Conference leaders supported the Camp Landon ministry through the Mennonite Central Committee, the inter-Mennonite relief and development agency begun in 1920 to provide famine relief to Mennonites in Russia, and would later confront the legacy of segregation when they took full responsibility for the project in 1957.

|

Mennonites from across the country joined the Camp Landon volunteers in grappling with segregation. In Pennsylvania, the Lancaster Conference’s Eastern Board continued to segregate mission work in Steelton in 1944 and decided to segregate the Newlinsville mission in 1946.24 In the Virginia Conference, segregated receipt of sacraments remained in force, and in 1947 the conference-run Eastern Mennonite College refused to admit Ada Webb, a daughter of African-American convert and Broad Street member Roberta Webb. In 1944 theologian and professor Guy F. Hershberger, speaking on the topic of race relations at Goshen College, a Mennonite liberal arts school in northern Indiana, chided white Mennonites for expressing attitudes of racial superiority, hesitating to welcome African Americans into their fellowships, and espousing a belief in racial equality that they did not embody.25 Whether enforced through mission policy or enacted through individual choice, racial segregation infused the church during the 1940s.

Nonetheless, some Mennonites opposed segregation in their religious communities. In 1945 students at Bethel College, a school sponsored by the General Conference in Newton, Kansas, raised money for an African Methodist Episcopal choir that included a student who had attended the college four years earlier.26 White Mennonites from both General Conference and (Old) Mennonite communities called for an end to prejudicial behaviors in the church and urged racial unity, noting that “we are all part yellow, part brown.”27 At the same time, leaders from the (Old) Mennonite Church strictly interpreted the doctrine of nonresistance as they cautioned against involvement in “interracial movements and organizations who by political pressure or nonviolent coercion seek to raise the social status of the Negro and other racial minorities.”28 Such a separatist stance, however, allowed for other internal changes. In 1948 the Eastern Board of the Lancaster Conference recommended ending segregation in all of their retirement communities.29 Although not enforced for years to come, the conference’s recommendation paralleled the Virginia Conference’s decision to admit African Americans in 1948, a decision that led to Ada Webb’s enrollment at Eastern Mennonite the following year.30 Debates over segregation in congregations and sacramental practices continued through this period, but tentative signs emerged that African-American converts like Louis Gray, Susie Smith, and Nettie Taylor, from Bethesda in St. Louis, would be welcome at a few more Mennonite institutions. In these initial actions against segregation, Mennonites mirrored similar steps taken by other white Protestant denominations.31

Concurrent with these small changes, church press editors presented African Americans as spectacles for their readers. Staff of regional conference magazines and national journals highlighted photos of mission work with African Americans in Illinois, Michigan, Mississippi, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, with captions that pointed to the novelty or exoticism of African Americans’ relating to white Mennonites, a pattern common throughout many white-majority denominations.32 Through this period, the (Old) Mennonite Church’s annual yearbook identified African-American mission stations with the parenthetical label “(Colored).”33 Similarly, a photo of a wedding at Broad Street Mennonite Church in Virginia appeared beneath the caption, “A Mennonite Colored Wedding”; a picture of church planters James and Rowena Lark dressed in distinctive Mennonite plain attire appeared above the terse title “Zealous Larks”; and a 1948 photo caption described “boys and girls with . . . big black wistful-looking eyes . . . so polite and orderly” yet not knowing “what it is to play a real live game.”34 As the Reverend Rondo Horton would point out several years later, the novelty of Mennonite mission to African Americans underlined a final message of the period: the solution to the sin of racial discrimination lay in saving the souls and improving the physical condition of the African-American community. Press attention emphasized the spectacle of that ministry rather than racial subordination within the Mennonite church.

Alongside the focus on racial spectacle, the doctrine of nonconformity came to play a central role in evangelism across racial lines. Although leaders from both (Old) Mennonite and General Conference denominations had long interpreted nonresistance in similar ways, the two groups codified nonconformity differently. Through this period and beyond, General Conference polity allowed congregations significant autonomy. As a result, congregations interpreted nonconformity standards in their own terms. The (Old) Mennonites, however, took a more uniform approach. In 1943, as Mennonites grew ever more acculturated, one of the denomination’s national working groups, known as the General Problems Committee, proposed that nonresistance and nonconformity be established as tests of church membership. Members of the committee recommended that anyone who bought life insurance, belonged to a union, dressed immodestly, wore jewelry, attended the theater, or went to movies should forfeit his or her member status.35

Delegates eventually tabled the proposal in favor of a more conciliatory approach, but the action revealed (Old) Mennonite Church leaders’ continued concern about the need to curtail worldly behaviors.36 In response to these concerns, a few evangelists argued that such an emphasis on nonconformity complicated efforts to bring African Americans into the church. For example, writing from her work assignment at the Philadelphia Colored Mission, white “sister worker” Emma Rudy wondered in 1945 whether the doctrine of separation had “some bearing on small memberships” at the various African-American missions.37 Although white Mennonites born into the church tested the limits of the nonconformist restrictions, African-American converts discovered quickly that church leaders gave them less leeway to challenge the dictate. A nonconformity conference held in Chicago in 1948 made no mention of the emerging double standard.38 In subsequent years, the racial disparity would become even more pronounced.

During the era of evangelism, white Mennonites approached African Americans with a mixture of hospitality, fascination, and rigidity. Peggy Curry, an African-American member of Broad Street Mennonite Church, would later describe the attitude of her white co-believers as an “iron fist [in a] velvet glove.”39 Although the evangelistic impulse brought Mennonites out of their white enclaves to serve and proselytize, their commitment to maintaining a separated order–especially evident among (Old) Mennonites–combined with assumptions of racial superiority to result in restrictive and controlling behaviors toward African Americans. Jamesand Rowena Lark countered this trend by starting churches in which conservative dress standards mattered less, but even their efforts could not counter in full the “superiority attitude” that theologian Hershberger ascribed to his co-believers.40 The promise of evangelism unfolded amid the hazards of separatist doctrine and segregationist attitudes. Only a few in the church imagined and embodied a more egalitarian community defined by the “way of love” that Horton would come to promote.

Racial Interventions, 1950-1955

The years 1950 to 1955 were a period of focused racial interventions, including organization, conferences, and correction. As the 1950s opened, African-American converts demonstrated their allegiance to the church. Like Rev. Rondo Horton, the new members claimed that they were “just Mennonite[s].” In accord with their assertion of Anabaptist identity, African- American Mennonites joined their white coreligionists to start new organizations, plan racial conferences, and correct racial grievances. White activist and scholar Guy F. Hershberger played an especially prominent role in fostering such initiatives. During this time, Mennonites also began to debate how best to respond to racial inequity. Denominational and congregational leaders in both General Conference and (Old) Mennonite communities no longer concurred that focused evangelism and provision of material resources would suffice. This lack of consensus expressed itself in debates over whether nonviolent campaigns like the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott contradicted the Mennonites doctrine of nonresistance.41 In short, discussions about race in the Mennonite church intensified.

|

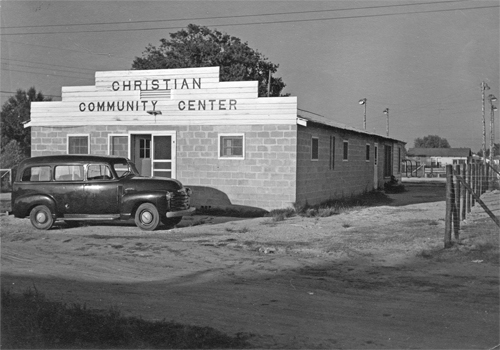

Stronger institutions supported such race-focused conversation. As 1950 opened, the (Old) Mennonite Church counted only 150 adult African- American members, but white Mennonites’ interactions with African Americans increased through eighteen African-American congregations and new home-based mission programs.42 With even greater fervor, Mennonites founded more than thirty-five new international missions through the course of the decade.43 Some Mennonites in rural settings, unable to leave their farms and businesses for overseas mission work, heeded calls to join the burgeoning missions movement by inviting children from the inner city into their homes. Most important, the Lancaster Conference began to send African-American children and youth into congregants’ homes for short summer stays through a Fresh Air rural hosting program enacted by the Colored Workers Committee in 1950. Although white children at first outnumbered African-American and Latino participants, program sponsors prioritized ministry to African-American children, and the program soon reflected that emphasis. The Woodlawn Mennonite congregation in Chicago also founded a General Conference-based Fresh Air program during this period. In addition to home-based ministry, the Lancaster Conference’s Eastern Board expanded their witness “to the colored” in 1950 and soon afterward started a racially integrated home for the elderly in Philadelphia.44 Meanwhile, General Conference leaders began to administer the Gulfport, Mississippi, Camp Landon service program in 1953, thereby lending stability and legitimacy to the longest- running African-American mission effort in the denomination. Such organizational attention brought new resources to previously cash- and resource-strapped mission stations.

|

National conferences also lent new authority to race relations ministries. In particular, gatherings organized in 1951 and 1955 by the Committee on Economic and Social Relations, under the leadership of Guy F. Hershberger, attracted the church’s attention. The 1951 event, held at Laurelville Retreat Center in western Pennsylvania, concluded with a call to “abolish” racial segregation and discrimination “wherever it may exist within our brotherhood.”45 At the time of the conference, a rumor spread that the church’s mission board had refused to rent a property to an African American for fear that doing so would reduce the property’s value.46 Whether or not Hershberger had this particular instance in mind when he raised his call matters less than the force of his position. He knew of many instances of individual and institutional discrimination in the church body. Hershberger used the authority of his position and the occasion of the conference to excoriate them.

Although segregation at many mission stations continued despite such egalitarian calls, other of his co-believers joined Hershberger in demanding an end to segregation and oppression. Women like white mission worker Leah Risser raised objections to racial divisions at the Steelton, Pennsylvania, station and elsewhere long before local administrators finally put an end to mission segregation.47 Other congregants from the (Old) Mennonite community involved in evangelistic outreach to the African-American community pointed out inconsistencies between church proclamations and members’ actions.48 Appeals based on scripture and on science appeared frequently.49 One writer captured a common sentiment of the era when he asserted, “Science has . . . confirm[ed] Paul’s view of the human race . . . [that] race is a biological unity.”50 General Conference writers noted similar inconsistencies and appealed to common humanity, but they had less practical experience to offer.51 With the exception of workers from Camp Landon in Mississippi, General Conference members faced a far more theoretical than practical question when they called for racial reconciliation.

This national and local attention to Mennonite racism opened the door to more extensive discussion during the 1955 Hershberger-initiated conference on the campus of Goshen College. At least 120 participants gathered in northern Indiana to hear an integrated slate of speakers representing the Mennonite church and other Protestant communities.52 Although no woman gave a plenary address, African-American Mennonite church planter Rowena Lark presented a short testimony, and Rosemarie Freeney, an African-American school teacher from Chicago who would later marry historian and activist Vincent Harding and figure prominently in civil rights work in the South, offered a devotional.53 Although clearly responding to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, conference organizers nonetheless dealt forthrightly with a broad range of racial issues inside the church based on carefully crafted, biblically informed presentations.54 Conference participants drafted a statement on racism that the (Old) Mennonite Church passed later that year. In addition to echoing the biblical and scientific arguments about racial unity that had been prominent in church publications for the previous four years, the statement called for corporate confession to the sin of racism and, perhaps most significant, asserted that there was no scriptural basis for opposing interracial marriage.55 Local and regional leaders acted on the statement’s appeal for confession and right conduct by rescinding the Virginia Conference’s segregation policy later that year.

Despite this organizational upswing, church leaders enforced dress and grooming codes far more strictly among African-American converts than among their white counterparts. The concern for adhering to a strict code of nonconformist behaviors had not abated among many (Old) Mennonite Church leaders, and the pressure built with particular intensity in the Lancaster Conference. In that setting, bishops struggled to maintain their authority in the face of growing acculturation and a burgeoning renewal movement brought to the United States by missionaries on furlough from ministry in Africa. Returning mission workers like Phebe Yoder and John and Catherine Leatherman emphasized grace over works, a message the bishops felt undermined their efforts to enforce nonconformity.56 Rather than follow the mediating influence of the African revivalists, white mission workers from the Lancaster Conference echoed the bishops. Pastors and mission workers used doctrinal statements and Sunday school lessons to instruct African-American women to wear the distinctive Mennonite prayer covering and cape dress, while church leaders also enforced male grooming restrictions. For example, during this period more than one Mennonite bishop required an African-American man to shave his moustache before baptism.57 In one instance, a bishop took an African-American man into a separate room and cut off the man’s moustache with a child’s blunt safety scissors.58

Similarly, during a 1954 Colored Workers Committee meeting, participants were asked, “Do we ask our new mission members to dress much plainer than members of home congregations?”59 The white mission workers in attendance decided in the affirmative. They stated that stricter requirements proffered a “blessing rather than a hindrance” to the African-American converts.60 Owing to the growth of African-American missions–twenty-nine congregations listed African-American members, and Sunday morning attendance reached nearly fifteen hundred–more African Americans came into contact with church strictures.61 By their own account, white Mennonites in the Lancaster and Virginia Conferences as well as other regions of the (Old) Mennonite Church thus sought to control African-American converts through dress and grooming restrictions.62

The period from 1950 through 1955 also saw an intense focus on interracial marriage. At this time, an overwhelming majority of white people in the United States opposed intermarriage, while African Americans proved more tolerant.63 A cadre of white Mennonite writers, debating the issue in the church press, focused on social rather than theological objections to couples’ marrying across racial lines and typically used the example of a black man marrying a white woman.64 The author of a General Conference article articulated the question he heard most often: “Do you want your daughter to marry a Negro?”65 Such examples reveal much. The writers first assumed that men, regardless of their racial identity, found white women more desirable than African-American women.66 The writers also accepted the notion that white men did not desire African-American women, despite centuries of evidence to the contrary.67 The women’s sexual interests did not register on writers who assumed that both African-American and white women passively accepted male advances.68 These assumptions carried a potent message. The writing and discussion of the period implied that a white Mennonite woman could not remain unsullied if she married an African-American man. Thus when committed church workers and life-long Mennonites Gerald and Annabelle Hughes celebrated their interracial marriage in 1954, leaders from the Ohio Conference expressed their displeasure by refusing to extend ministerial credentials to Gerald the following year.69 Few who knew of the Ohio Conferences’ censure against Hughes missed the irony that the national denomination passed a statement the same year removing all biblical censure against interracial unions.

The racial interventions from 1950 through 1955 often contradicted one another. Even as Freeney, Hershberger, Lark, and Risser condemned racially oppressive practices in the church, bishops and evangelists from the (Old) Mennonite denomination strictly enforced nonconformity dictates among African-American converts. While some leaders overturned segregation policies, others sustained objections to interracial marriage. Intensified discussions of race relations included both assertions of human unity and the feared threat of black encroachment. The volunteers who staffed the high-profile ministry to African Americans at Camp Landon often attended local Mennonite congregations that rebuffed African Americans. The many contradictions of this period sprang from a church theologically committed to evangelism and racial equality while culturally immersed in separatist behaviors and prejudiced attitudes. No wonder then that Rev. Rondo Horton enjoined his coreligionists to discontinue evangelizing African Americans in favor of teaching white southerners “the way of love.” He knew that the Mennonite church could often prove unwelcoming, if not hostile, to the African-American community.

1. Quoted in Guy F. Hershberger, “Report of the Chicago Race Relations Seminar,” memorandum, July 16, 1959, 8, CESR papers I-3-7, box 7, folder 58, AMC.

2. “The Mennonite Churches and Race,” Gospel Herald, May 19, 1959, 460.

3. Hershberger, “Report of the Chicago Race Relations Seminar.”

4. Bechler, Black Mennonite Church, 38.

5. Ibid., 39-41.

6. The periodization I offer here leans heavily on the work originally developed by J. Denny Weaver in his insightful treatment of Mennonite written materials on race. See Weaver, “The Mennonite Church.” Although I have renamed and expanded the evidentiary base for each of the periods and made slight adjustments to some of the beginning and ending dates, the basic framework comes from Weaver’s work.

7. Gingerich, “Sharing the Faith”; Hinojosa, “Making Noise.”

8. Bechler, Black Mennonite Church, 41.

9. Merle W. Eshleman, “Mission for Colored, Philadelphia,” Missionary Messenger, February 16, 1936, 11.

10. Shenk, By Faith They Went Out, 40.

11. Ibid.

12. Peggy Curry, interview with author, March 29, 2005.

13. Weaver, “The Mennonite Church,” 19.

14. Exact membership numbers are not available before 1950, but an estimate of 150 or fewer is consistent with the statistical data included in Le Roy Bechler’s foundational text. See Bechler, Black Mennonite Church, 172. Awareness of disparate racial experience emerges from numerous oral histories conducted for this project. See, in particular, Curry, interview.

15. Daniel Kauffman, editorial, Gospel Herald, January 7, 1943, 865.

16. Schlabach, Gospel versus Gospel, 259.

17. Orie O. Miller, minutes of the Sixty-Third Quarterly Meeting of E.M.B. Of M. & C. And Lancaster Conference Board of Bishops, January 2, 1943, LMHS.

18. Shenk, By Faith They Went Out, 76.

19. Ibid.

20. Bechler, Black Mennonite Church, 172.

21. Melvin Gingerich, “Negroes and the Mennonites,” The Mennonite, June 14, 1949, 4.

22. Haury, Quiet Demonstration, 22.

23. Lois Barrett Janzen, “Gulfport: Discovering What It Means to Be White among Blacks,” memorandum, November 9, 1973, 2, VII.R GC Voluntary Service, Series 11 Gulfport VS Unit, box 6, folder 214, Reports, misc., MLA; Edna Moran, interview with author, May 24, 2005; Sue Williams, interview with author, May 25, 2005.

24. The (Old) Mennonite Church consisted of regional governing bodies such as the Lancaster and Virginia Conferences. The Lancaster Conference, the largest of the conferences, did not officially join the (Old) Mennonite denomination until 1971, although it did maintain a number of fraternal ties before that date. The Lancaster Conference extended its reach up and down the East Coast from New England to Florida. The vast majority of the Lancaster Conference congregations, however, clustered in and around Lancaster County in southeastern Pennsylvania.

25. Guy F. Hershberger, “Race Prejudice in America Today,” memorandum, March 8, 1944, CESR papers I-3-7, box 7, folder 55, AMC; Schlabach, “Race, and Another Look,” 3.

26. Reynold Weinbrenner, “Right Race Relations,” The Mennonite, February 6, 1945, 3.

27. Irvin B. Horst, “Mennonites and the Race Question,” Gospel Herald, July 13, 1945, 284-85; Dale M. Stucky, “Science Also Says, ‘All of One Blood,’ ” The Mennonite, February 5, 1946, 4.

28. Horst, “Mennonites and the Race Question,” 285.

29. On September 14, 1948, at the suggestion of the Colored Workers Committee, the Eastern Board decided to recommend to the joint board that “the care of our aged members in our several institutions be without race discrimination.” See minutes of the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities Executive Committee Meeting, September 14, 1948, 1, LMHS.

30. Minutes of Eastern Mennonite College Administration Committee, September 20, 1948, box II-B-4, John R. Mumaw Collection, box 27, EMU.

31. Reimers, White Protestantism, 111.

32. On this point, I disagree with J. Denny Weaver’s finding. He notes that during the period from 1945 to 1949, church press reports gave only low-profile attention to African-American missions. (Note slight difference in periodization. I begin this period in 1944, with the founding of Bethel Mennonite in Chicago.) See Weaver, “The Mennonite Church,” 23. Examination of regional press reports shows, however, that African-American Mennonites like James Lark were already receiving significant attention from church leaders and mission boards during these five years.

33. Daniel D. West, “What About Our Negro Missions?” Missionary Messenger, January 1946, 1; Zook, Mennonite Yearbook and Directory 1946. The practice of designating congregations as “Colored” had begun to dissipate by 1950 and was discontinued entirely by 1956. See Zook, Mennonite Yearbook and Directory 1956.

34. Stanley Shenk, “A Mennonite Colored Wedding,” Gospel Herald, December 2, 1947, 782; “Zealous Larks,” Missionary Guide, ca. 1947, 16; Turkey Creek Bible School, photo, Gulfport, Miss., The Mennonite, February 24, 1948, 15.

35. Toews, Mennonites in American Society, 76.

36. James M. Lapp, “Conferences and Congregations: A Review of Mennonite Church Polity,” Historical Committee and Archives of the Mennonite Church, www.mcusa-archives.org/MHB/Lapp.html (accessed March 10, 2009).

37. Emma H. Rudy, Abraham L. Gehman, and Esther K. Lehman, “From Our Negro Stations,” Missionary Messenger, January 1946, 5, 7.

38. John L. Stauffer, Introductory to Non-Conformity Conference, Chicago, Illinois, memorandum, Oct. 19-20, 1948, box I-MS-17, John L. Stauffer Collection, Misc. folders of Notes and Outlines, etc., box 8, VAMC.

39. Curry, interview.

40. Hershberger, “Race Prejudice in America Today.”

41. Weaver, “The Mennonite Church,” 31.

42. Bechler, Black Mennonite Church, 172. The figure of 150 African-American church members did not include infants, children, youth not yet baptized, or regular participants who had not yet officially joined the church. Actual African-American participation was most probably in the neighborhood of a thousand on a given Sunday during this period.

43. Shenk, By Faith They Went Out, 79.

44. On October 26, 1950, the Lancaster Conferences’ Eastern Board and Bishop Board discussed the executive committee’s “concern for counsel and advice on how to expand our witness and service in the work to the colored and for colored members” and referred the action to subcommittee. See Orie O. Miller, minutes of the Eastern Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities and Lancaster Conference Bishop Board, October 26, 1950, 1, LMHS. On March 8, 1954, the Lancaster Conference’s Eastern Board established the Philadelphia home for the aged and declared that it was open to “male and female guests irrespective of race.” See minutes of the Eastern Mennonite Board Executive Committee, March 6, 1954, LMHS; Good, “Forty Years,” 21.

45. “Statement of Concerns of the Study Conference on Christian Community Relations,” memorandum, July 24-27, 1951, 4, CESR papers I-3-7, box 2, folder 35, AMC.

46. Schlabach, “Race, and Another Look,” 4.

47. William Yovanovich, “Leah Risser, Ahead of Her Time,” WMSC Voice, November 1990, 5-7.

48. Le Roy Bechler, “Meeting the Challenge of the American Negro,” Missionary Messenger, February 1952, 2; J. Lester Brubaker, editorial, Missionary Messenger, October 1950, 3; J. D. Graber, “An Open Letter to Ministers and Christian Workers of the Mennonite Church,” Gospel Herald, January 12, 1954, 40; Robert Stoltzfus, “A Short History of Mennonite Work among the American Negro,” Missionary Messenger, October 1950, 12.

49. Robert M. Labaree, “Can Christianity Solve the Race Problem,” Gospel Herald, May 13, 1952, 473; Carl M. Saunders, “There’s No White Blood,” Gospel Herald, November 3, 1953, 1060.

50. Grant M. Stoltzfus, “Biological, Social, and Spiritual Aspects of the Race Problem,” Christian Monitor, 1951, 14.

51. See the following articles in the The Mennonite: “A Primer on Race,” February 6, 1951, 94-96; D. W. B., “Do You Want Your Daughter to Marry a Negro?” October 28, 1952, 684; William Keeney, “Reborn Color-Blind,” January 8, 1952, 22, 25; Olin A. Krehbiel, “The Ministry of Reconciliation,” April 4, 1950, 220, 24; Esko Loewen, “What Do You Want to Do, Marry a Negro?” February 6, 1951, 95; J. N. Smucker, “Mennonites and the Race Question,” January 8, 1952, 19; Esther Soderholm, “White Supremacy,” October 6, 1953, 618.

52. Schlabach, “Race, and Another Look,” 6.

53. Ibid.

54. “Christian Race Relations” (proceedings of the Committee on Economic and Social Relations of the Mennonite Church, Mennonite Community Association, Goshen, Indiana, April 22-24, 1955).

55. Mennonite General Conference, “The Way of Christian Love in Race Relations” (statement passed at Mennonite General Conference, Hesston, Kansas, August 24, 1955).

56. MacMaster and Jacobs, A Gentle Wind of God, 90-91, 98, 186.

57. Although the objections to moustaches in this era arose from a concern about the association of this grooming choice with the military, the bishops’ rigorous enforcement appears to have been racially triggered.

58. References to this instance at Newtown Gospel Chapel, Sarasota, Florida, appear in three separate oral history interviews with the author: Michael Shenk, March 19, 2003; Dave Weaver and Sue Weaver, May 26, 2005; Paul Zehr, March 1, 2003.

59. Notes of the Colored Workers Committee, 1953-57, 1-4, file cabinets far wall, first cabinet, top drawer, drawer marked Home Missions Locations and Other General 1956-1964, four numbered notebooks, EMM record room.

60. Ibid.

61. Bechler, Facts, Considerations, and Membership.

62. White converts also received instruction in the importance of wearing nonconformist dress. As the sources cited here demonstrate, however, white mission workers enforced those requirements for African-American converts with a relatively greater degree of intensity. Other examples of enforced dress and grooming requirements are cited in Curry, interview; Norman Derstine, “Dear Brothers and Sisters in the Lord,” memorandum, Trissels Mennonite Church, 1955, box I-MS-17, John L. Stauffer collection, General Files H-Z, box 6, folder Nonconformity, VAMC; William M. Weaver, e-mail messages to author, January 30, 2003.

63. Romano, Race Mixing, 45, 83-84, 107-8.

64. See, for example, D. W. B., “Do You Want Your Daughter to Marry a Negro?”; Paul Erb, “Interracial Marriage,” Gospel Herald, June 24, 1952, 611; Levi C. Hartzler, “Race Problem Unnecessary,” Gospel Herald, February 8, 1955, 137, 40. As discussed at length in chapter 6, even the 1955 (Old) Mennonite Church statement on race relations hedged support of interracial marriage with social rather than theological references: “The social implications of any proposed union should receive careful attention.” See Mennonite General Conference, “The Way of Christian Love in Race Relations,” 6.

65. D. W. B., “Do You Want Your Daughter to Marry a Negro?”

66. I am here indebted to the work of Ann Taves for her insightful exploration of the sexual body in the American religious tradition. See, especially, Taves, “Sexuality,” 28, 41, 56.

67. D’Emilio and Freedman, Intimate Matters, 14; Romano, “Race Mixing,” 5.

68. Thanks to Christina Traina, of Northwestern University, for adding this insight.

69. Annabelle Hughes and Gerald Hughes, interview with author, August 29, 2006; Gerald Hughes, e-mail message to author, January 19, 2007; Miller, “Building Anew in Cleveland,” 84.