Victoria Janzen is a May 2010 graduate of Bethel College, with majors in history and Spanish. Originally from Wichita, she plans to begin a teaching job at McPherson High School in August.

Early 1980s background: An environment of nuclear proliferation and the peace surge response.

The Ribbon Project was a protest against nuclear proliferation, active between the years 1982 and 1985. In its final form, a giant ribbon united thousands of smaller ribbon segments from around the country, which were placed around the Pentagon building in Washington, D.C.1 In its entirety, The Ribbon included participants from every state in the United States, as well as participants outside of the United States.2 Kansans responded positively to The Ribbon. The form of The Ribbon was particularly appealing to Kansas women, matching their beliefs about responsible political protest. Furthermore, the Ribbon’s design fit the values and strengths of Kansans. High participation and overall success resulted.

To put the project and its goal in context, it is important to examine the status of arms control in the early 1980s. International arms buildup characterized the early years of this decade. Détente, a period of relaxed relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, ended in 1980,3 provoking an arms buildup worldwide. For example, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) decided it needed a strategy for combating Soviet “military and nuclear superiority.”4 As a result, NATO adopted a dual-track diplomacy strategy: First, NATO “[attempted] to negotiate with Moscow [the Soviet Union] for the reduction or even elimination of the Kremlin’s intermediate range SS-20 missile.”5 If this failed, the second part of the dual-track strategy called for “equivalent U.S. weapons [to] be deployed in western European countries,” thus meeting Soviet arms with equal force.6 This strategy intensified military armament in the United States, other NATO countries, and the Soviet Union.

Yet the United States engaged in arms-building measures beyond those of NATO. In late 1980, U. S. President Ronald Reagan instituted “nuclear weapons modernization programs” like the MX missile program which modernized land-based missiles vulnerable to Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles. Moreover, Reagan reinstated the B-1 bomber program, designed to create a stealth aircraft capable of dropping bombs.7 Thus the early 1980s, especially for the United States, was a period of serious arms buildup that saw the United States engaged in wide proliferation.

Aside from the threatening existence of nuclear arms, there were other nuclear concerns:

Between 1945 and 1986 global ‘background radiation’ (radiation found in the environment from both natural and synthetic causes) increased by [thirteen] percent due to nuclear weapons testing and radioactive wastes generated by nuclear energy production.8

By 1982, “There were approximately [fifty thousand] nuclear weapons in the world.”9 Furthermore, “dozens of nuclear weapons accidents, many of them unknown to the majority of the U.S. public,” had occurred prior to The Ribbon project.10 Thus there were other reasons to fear nuclear weapons technology aside from the obvious destruction related to nuclear bombing. The creation, storage, and testing of nuclear technology posed serious threats. In this environment, a surge in U.S. peace activities began. The Ribbon was one of those.

Sociologist and historian John Lofland suggests that “elites goading events in 1981-1983” created the rise of peace activism in the early 1980s.11 Lofland explains that the actions of the Reagan Administration created great concern about nuclear armament in the United States and around the world:

Doomsday perceptions and fears were the proximate engines or drivers of the 1980s surge of peace activism. Perceptions of crisis had, of course, their own causes, the bellicose behavior of the Reagan administration foremost among them.12

Lofland views Reagan’s “aggressive military stance among the nations of the world” as an effort to reestablish U.S. military dominance “and thereby make U.S. “patriots glow with pride.”13 However, such actions also alarmed many Americans, and an increase in peace activism resulted.14

Historian Amy Swerdlow agrees that “U.S. citizens [surged] in opposition to newly militant U.S. government foreign policy in the early- and mid-eighties.”15 Indeed, “participation in the range of ten million by the mid-eighties is well documented … Against a baseline of a quarter million peace workers in the late seventies (at best), this is an impressive change.”16 Swerdlow adds that the peace movement at this time was largely based in women’s culture: in “the 1980s the many new organizations and the women’s culture – self sufficient with exciting literature, music, and intellectual debate – filled the women’s rights peace movement with renewed energy.”17,18 The Ribbon Project was consistent with this trend of incorporating women’s culture into peace activism. Justine Merritt, founder of The Ribbon, recalls her decision-making process. She wanted “the project to offer ‘personalization’” and for “the form of art itself to be specific to women’s experience.” Finally, it was decided that “needlework was an expressive medium that would appeal particularly to women because of their historical familiarity with the textile arts.” The Ribbon did not limit participation to women; in fact, “the project was presented to the public and the media as one in which many types of people could participate.”20 Yet The Ribbon was clearly based in women’s culture, connected to trends of the women’s movement and the larger 1980s peace movement.

While Swerdlow discussed how women influenced the culture of the early 1980s peace movement, Lofland identified a “paradox” within the movement: “There was something disproportionate in the relation between the gravity of the crisis mindset and the restraint of politely protesting action. If matters were really as dangerous and threatening as many people asserted, perhaps much stronger and ‘radical’ actions were in order.” According to Lofland, “Not only was there virtually no physical violence, there was even little verbal violence, by which I mean the kind of angry, fist-shaking rhetoric that is fairly common in at least some segments of many other movements.” Despite high anxiety over nuclear armament issues and high numbers of Americans involved in peace activism, protest remained “quite restrained and civil” during the early 1980s.21

Merritt often articulated her desire for The Ribbon to be non-threatening in nature: “The Ribbon project has gotten cooperation from the Washington Police Department, U.S. National Park officials and Pentagon security because we haven’t been hostile”.22 The Ribbon was compatible with characteristics of early 1980s peace activism.

Linda Pershing explored the reasoning behind The Ribbon’s restrained protest in her work The Ribbon Around the Pentagon: Peace by Piecemakers. Pershing suggests restraint was the result of two factors: first, lessons learned from the 1960s; and second, an attempt to appeal to the constituency of the present, concerned with family and community perceptions of appropriate female behavior:

Ignacio panel maker Elizabeth Mantey commented that she was involved in peace demonstrations during the Vietnam War, when protestors were labeled antisocial or communist. … she realized that her husband was disturbed by some of her activities and that her actions could have consequences for his standing in the community.23

The extreme nature of 1960s activism, fresh in the minds of potential participants, had to be avoided in order to appeal to American society in the 1980s. In this context, The Ribbon’s non-threatening platform makes sense.

Yet this choice of medium did more than connect it to contemporary peace demonstration practice. The medium chosen for The Ribbon directly related to what was appealing to women. Merritt recalled this decision-making process and recounts how she wanted “the project to offer ‘personalization’ and an art form “specific to women’s experience.” National organizers decided “needlework was an expressive medium that would appeal particularly to women because of their historical familiarity with the textile arts.” Thus national organizers made the decision that The Ribbon would be composed of canvas pieces decorated with textile arts.24 Because the chosen medium was fabric, “The Ribbon was rooted in a historical practice that made the medium appealing to certain segments of the populace. In this case, the project drew on a longstanding tradition of women using fabric to express their values, social concerns, and political allegiances.”25 In this sense, The Ribbon was not unique. Women had long exploited their traditional domestic roles within society to express social concerns. For example, in the late 19th century, women participated in abolitionist fairs and employed their domestic and moral boundaries to contribute to social change: “The Bangor Sewing Circle … was hard at work creating items to sell at the fair … Country women were asked to contribute butter and cheese to the fair as well as a hundred weight of maple syrup.”26

Kansas women, in particular, had a history of citing their domestic expertise as justification for entry into the political sphere. Movie censorship occurred in Kansas between 1915 and 1966.27 Kansas women were the driving force behind this political action, citing the need for “clean pictures for [their] children.”28 Not only did they demand and achieve movie censorship throughout the state, Kansas women formed the body that governed statewide censorship: “Mrs. Gertrude Sawtell served as chairwoman of the Kansas State Board of Review, with Mrs. Luther Swensson and Mrs. Eleanor Tripp assisting as fellow censors.”29 This panel of three women controlled film shown throughout Kansas for a period of 50 years.

Aside from movie censorship, “women’s influence was important in advancing public health consciousness and practice in Kansas.” Kansas women created he “Fresh Air Baby Camp” was created to help infants with low birth-weights survive. Kansas women were also responsible for establishing hospital maternity care in the state. “A mother and her thirteen-year-old mentally retarded son appeared before the Kansas legislature” and helped persuade the Kansas Legislature to create the Division of Child Hygiene.”30

In 1880, Kansas women used their “moral suasion” to pass a state constitutional amendment prohibiting alcohol sales and consumption. This prohibition, instituted at the urging of Kansas women, took place long before the national ban. Kansas women wielded a unique political power. Surprisingly, prohibition continued in Kansas in certain counties until the 1980s, suggesting that traditional gender roles or concepts of behavior remained ingrained throughout the 20th century.31 Women across the United States, and particularly in Kansas, have a long history of exercising their traditional domestic sphere as a weapon for promoting social change.

Yet other aspects of The Ribbon were reminiscent of past social protest demonstrations. The idea of women surrounding a government building in protest was not unique to The Ribbon. In 1972, “two thousand women formed a ‘Ring Around Congress’…demanding that Congress vote to cut off funds for the Vietnam War.”32 While The Ribbon as a whole was a unique concept, many aspects of the project had been previously employed by women seeking to promote social change in the United States.

Harriet Hyman Alonso reinforced this idea in her book Peace as a Women’s Issue: A History of the U.S. Movement for World Peace and Women’s Rights. According to Alonso, the women’s peace movement has historically held the “conviction that women must be responsible citizens, not only locally, but nationally and internationally as well. … Like the social housekeepers of the Progressive Era.” Alonso offers an example:

The very first organized feminist peace organization, the Women’s Peace Party (1915), consisted largely of suffragists who stressed that the elimination of war was not possible unless women not only had the right to vote but also made up half of every nation’s governing body.33

This supports the idea that women’s organizations and activists had long considered peace to be within their domain of expertise and influence. Alonso explains the reasoning behind this assumption: “Women, as the child bearers of society, have a particular interest in peace – namely, not wanting to see our offspring murdered either as soldiers or as innocent victims of war.” In short, feminist peace activists argued that women needed political power because motherhood makes women expert protectors of children and society. Alonso explained that “almost every [women’s activist] group involved has itself portrayed women as more sensitive, more caring, more thoughtful, and more committed to producing a humanistic and compassionate world than men as a whole.”34 The focus on motherhood

has provided women a socially acceptable cover for their highly political work. It has [given] them a certain amount of credibility. It has … allowed women to present a self-image of moral superiority. Above all, it is the most successful organizing tool available to women.35

Merritt recognized how important self-representation was to women who participated in The Ribbon: “The expression of social and political concerns through the fabric arts represents an attempt by women to make themselves visible on their own terms, to re-present themselves.”36 Echoing another point made by Alonso, Merritt described the organizing role motherhood played in The Ribbon:

Several women with whom I spoke indicated that they thought their involvement with the project as a legacy for the next generation. They wanted their children to know that their mothers and grandmothers had worked for peace, hoping to encourage them to do likewise when their grown.37

Clearly, the Peace Ribbon Project successfully encouraged women to participate by utilizing fabric arts and emphasizing an historic role of women as peacemakers. Perhaps most importantly, the project provided women an opportunity to make their opinions (and themselves) visible.

Traditional female fabric arts were central to The Ribbon. Therefore the project, like many women-based peace movements before, sought credibility through its basis in a perceived women’s culture. Not only was the medium of expression (fabric art) rooted in women’s culture, but the content of the fabric panels were likewise rooted in female culture. According to Opal May Evans and Evelyn Steimel, “Children, nature and music themes were often seen” in Ribbon panels from Kansas.38 Additionally, the prevalent themes in the Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution Ribbon Collection include children, home, and religion.39 Fabric panels from Kansas demonstrated female expertise in domestic matters as well as fabric art. The Ribbon sought credibility for nuclear proliferation concerns through historic claims that women have a long history of using their traditional domestic sphere as a tool for promoting social change.

Factors that contributed to The Ribbon’s success in Kansas

Despite low initial expectations, The Ribbon attracted a huge following of women across the country who wanted to facilitate social change through this project. In total, “Over 30,000 panels were received from the entire nation for display in Washington, D.C. on August 4, 1985.”40 The national project’s initial goal was to create a mile-long piece of Ribbon.41 In its final form, The Ribbon formed “a 15-mile long Peace Ribbon … that surrounded the government buildings, from the Capitol to the Pentagon, in Washington.”42 One reason for this success may be because The Ribbon paralleled the popular peace activism of the early 1980s. Its claim to legitimacy through the traditional domestic sphere and the restrained form of protest are both strategies representative of the larger peace movement of the early 1980s. In Kansas, high participation, accompanying peace projects, and the generation of publicity led to the project’s success.

Participation in The Ribbon was not equally distributed around the country. Kansas was a serious contributor of Ribbon segments, creating a total of 1,114 pieces.43 In total, the national Ribbon received approximately 25,000 segments,44 originating from 47 of the United States plus Canada and a few selected other countries. Kansas, one of approximately 49 source locations, contributed 4% of total Ribbon segments. Considering this significant contribution, it is interesting to note that Kansas originally projected the creation of only 40 ribbon segments.45

Evans and Steimel recount in their work The Story of the Kansas Ribbon: Kansans Share a Vision of Hope, Joy and Peace that “thousands of people involved in all areas of the state of Kansas [were] proof that there [was] much concern about nuclear war and that the people of Kansas [wanted] peace.”46 Moreover, at the 1984 Ecumenical Assembly, Kansas had the best Ribbon showing: “Opal May Evans packed two large boxes containing 226 pieces. Kansas had more pieces than any other state at the Assembly.”47 The high level of participation among Kansans illustrates that The Ribbon’s aim – ending nuclear proliferation – resonated with Kansans.

Aside from participation, there are other reasons to suggest why The Ribbon was successful in Kansas. Organizers of The Ribbon in Kansas created accompanying projects to spread The Ribbon’s message against nuclear proliferation. The State Board of Church Women United (CWU) held a celebration of The Ribbon “at the Kansas State Capitol on June 2, 1985.”48,49 Evans explained, “We worked so hard getting the ribbon to go to Washington … I wanted to show it off in Kansas first, and give [Kansans] an opportunity to see it.”50 The Kansas celebration was highly organized. It included an address from Lt. Gov. Tom Docking, a speech from Jill Jackson Miller of Beverly Hills, Calif., who composed, “Let There Be Peace on Earth and Let It Begin with Me,” and a chorus of schoolchildren.51 According to Evans, president of the CWU Board at the time of The Ribbon in Kansas, the event garnered a good turnout. While other states conducted celebrations of The Ribbon apart from the national project, Evans emphasized that the Kansas state celebration “was strictly our idea.”52 Initiative and organization for such events originated from state organizers. The high turnout at Kansas’ celebration may have been due to the extensive program of events and publicity facilitated by state leadership.

Kansas organizers planned many more accompanying projects during the years of The Ribbon. In 1984, the CWU Board organized a “Mini-Peace Causeway” Through which participants visited the Wolf Creek nuclear plant at Burlington and Boeing Industries in Wichita53 to apply The Ribbon’s message of peace and nuclear disarmament to Kansas realities. The extension of Ribbon-related events demonstrates how thoroughly nuclear disarmament awareness took root across Kansas.

But Kansans did not stop there. Organizers planned “Community and state sew-ins”.54 The Dominican Sisters Motherhouse in Great Bend, Kansas, conducted a “Ribbon Sew-In” which included more than just Ribbon sewing. An advertisement for the event read: “Experience Reflections, songs and artistic expressions of Peace.”55 The event proved successful, with 30 Western Kansas women in attendance and 102 Ribbon segments sewn together. This event, in a small town in western Kansas, had important meaning for participants worried about the impact of war and violence. The success of such a local event points to the high level of commitment Kansans had to The Ribbon.

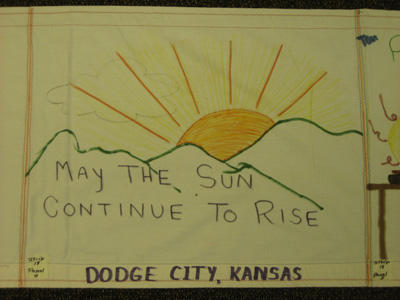

During The Ribbon’s three years of preparation, local events like the Ribbon Sew-in were common. For instance, “In Dodge City several groups were actively designing and making Ribbon segments, often dedicated at special prayer and/or discussion meetings.”56 Goodland held a peace rally on Good Friday during which ecumenical leaders sewed for peace.57 Likewise, the “Clay Center Church Women United group held a public exhibit to air their Ribbons and let others be inspired by the folk art displayed.”58 Small communities around the state engaged in celebrations and meetings that encouraged participation and spread the message of The Ribbon.

Often, such participation took place in church communities. A host of Beloit churches joined the project. According to the local paper, women at these churches “decided to depict things they couldn’t [bear] to lose in a nuclear war.”59 The Ribbon obviously had great importance to these Kansas communities.

Participants even sent “expressions of gratitude” to state organizers for providing them with this opportunity. Church women from Nortonville attached a message along with their ribbon contribution: “It is with pleasure that the church women of Nortonville, Kansas submit this banner as a small part of a Peace Ribbon to be tied around the state capitol in Topeka on June 2, 1985. We are happy to have taken a part in this Peace Movement.”60

Such positive feelings on the part of participants translated to positive publicity. Local publications around the state made announcements and provided updates about the progress of The Ribbon in Kansas.61 The Ribbon was featured in numerous publications throughout the state. For example, the project received an endorsement from Zula Bennington Greene, or “Peggy of the Flint Hills,” a popular Kansas columnist during the 1980s.62 She provided “helpful publicity” for the Peace Ribbon in Kansas by writing a “Plea for Peace” in her column, “Peggy of the Flint Hills.”63 Evans recalled her excitement over learning “Peggy” had lent her column to helping out Kansas’ ribbon effort.64 Evans’ excitement concerning the publication is understandable, considering the piece specifically complimented her work: “The idea is a great united plea for peace by the churches of this nation. It originated with Justine Merritt, Denver, three years ago. When Opal May Evans read about it, the idea took fire and she organized Kansas.” From Kansas City to Hutchinson, Topeka to Junction City, Lakin to St. John, periodicals around the Kansas advertised The Ribbon.65

|

Aside from local publications, Kansans publicized The Ribbon through personal contact. Evans testified that The Ribbon was successful in Kansas because people networked within social groups. Additionally, Ribbon participants visited local organizations like schools and shelters to promote the project. Typically, they provided an introduction the project and brought Ribbon pieces.66 The publicity from around the state fueled a high level of interest in The Ribbon.

Kansas politicians eventually began acknowledge the project. United States Senator Nancy Kassenbaum acknowledged the Kansas Capitol celebration: “It is a pleasure to send my best wishes for today’s Peace Sunday Celebration … Throughout history, mankind has had many concerns and goals in common, with one of the most important being the desire for a lasting peace.”67 Senator Bob Dole expressed his regrets at not being able to attend the event: “I regret I cannot be with you to enjoy the fellowship of this important day. Your invitation to worship with you at the Peace Sabbath service is indeed an honor.”68 Kansas Governor John Carlin was also unable to attend the Kansas Capitol event, but wished participants and planners “great success with the celebration.”69 Kansas politicians might have been afraid to attend for political reasons. Senator Dole, for example, repeatedly supported nuclear proliferation measures.70 Nevertheless, Kansas Ribbon participants forced politicians to consider their stance on nuclear proliferation.

One political contribution was Governor Carlin’s declaration of June 2, 1985, as Peace Ribbon Day.71 Evans realized this declaration would have no long-term impact in spreading The Ribbon’s message, but was rather an immediate recognition of the importance of Kansas women’s work on this issue in 1985.72

Such hard work created serious results for Kansas. The most important contributor to the state’s success was the high level of citizen participation. From the high numbers of Ribbon segments to the variety of involved Kansas communities, participation was strong. A selection of accompanying projects furthered The Ribbon’s message against nuclear proliferation. The Mini-Peace Causeway, Ribbon Sew-Ins, local exhibitions of Ribbon segments, prayer services, peace rallies, and church community work all reinforced and spread the message of The Ribbon. Kansans also made the project successful by creating publicity around the state and bringing the issue of nuclear proliferation before their state’s politicians.

How the form of The Ribbon created appeal in Kansas

Besides these factors, the form of the project built interest among Kansans. Kansans who completed The Ribbon Questionnaire (all women) overwhelmingly cited the form of The Ribbon as a reason for involvement.73 For some Kansas women, the simplicity of the project was attractive. According to others, the positive nature of The Ribbon was interesting. It was an invitation for them to use their talents.74 Evans recalled how the form of The Ribbon encouraged participation among Kansans:

Anyone could be a part of it real easy, and it didn’t matter maybe you were a quilter … and maybe you were an artist with paints, or whatever was your thing … your hobby … you could use it to make the peace ribbon and be a part of the whole thing, and I think that that made a lot of difference.75

While Evans mentioned the inclusive nature of The Ribbon’s form, participant Christine Buller discussed how the incorporation of fabric arts, specifically, attracted “many [Kansans] who [were] still skilled in the old-fashioned fabric arts of quilting, appliqué, and embroidery.” Sewing circles and quilting groups were already common in Kansas at the time of The Ribbon. Kansas women were excited to send a message “affirming life” through an activity already common in their daily lives.76 Edith Stucky for example, thought “the Ribbon Sew-in was a thrilling experience.”77

The Ribbon transformed the crafting skills of Kansas women into a powerful statement concerning world politics. It also affirmed their identities as crafters and as women. While the form of The Ribbon allowed Kansas women to use arts with which they were acquainted, a greater motivation came from the connection between craft work and political change.

Appeal was generated due to The Ribbon’s positive and non-confrontational nature. Buller noted The Ribbon project “could be a very positive one in demonstrating the worth of human life and the beauty of our world.”78 She discussed the project’s non-confrontational nature: “It didn’t require marching in a protest demonstration or writing a letter to a congressman. But an individual could still make a powerful statement on what, in life and on this earth, is important.” 79

In the same vein, the CWU Board adopted The Ribbon and “approved [it] as a non-political, non-violent statement of faith, a proclamation to the world that we do not accept nuclear war as inevitable.”80 Both at the time of participation and through reflection on their experiences, Kansas women highlighted the positive nature of The Ribbon. One participant linked high participation to Kansas values: “[Kansans] are neighborly and cooperative.” This project was a respectful way for the predominantly female participant pool to express their opinions.81 It was important to Kansas women that protest remain respectful and non-confrontational, adhering to traditional gender norms prohibiting aggressive behavior in women.

Indeed, the national Ribbon demonstration took place on a Sunday in an effort to avoid confrontation. Pentagon workers were not subjected to face-to-face interaction with protestors. Instead, participants protested on a Sunday and left their Ribbons as a silent but powerful message. Pentagon employees came to work on Monday August 5, 1985, to a sight of 25,000 Peace Ribbon segments asking them to halt nuclear armament practices.82 This non-confrontational method of protest was consistent with traditional gender norms that were especially important for recruiting Kansas participants.

The Ribbon also offered Kansas women an opportunity for expression. Many Kansas Questionnaire respondents cited the opportunity for expression as motivating their participation: “express oneself,” “express fears,” “have my voice heard on peace issues,” “express loyalty as an American … for peace and justice,” “creative expression of peace/justice,” and to develop a “joyous expression of love of life.” The Ribbon provided Kansas women an acceptable platform on which they could express themselves.

However, the values and priorities among Kansans themselves led to successful execution of the project. CWU leaders in Kansas used grassroots methods to grow the project. The organizational structure of The Ribbon in Kansas points to the importance of grassroots culture in the project’s success. Evans recalled, “My house became the headquarters for The Ribbon in Kansas. We had a great basement where we had our meetings and where we did a lot of the work and planning.”83 The willingness of Kansans to do things on the local level lent to the success of the project. When asked if there was something distinctive about the Kansas environment that led to project success, participant Anita Bohn said no. However, she followed up by stating that in Kansas, the project “was done from a grassroots level,” suggesting that local networking was a distinctive part of the Kansas environment that led to The Ribbon’s success.84 Grassroots culture in Kansas aligned with The Ribbon Project’s need for participants to contribute personal resources and connections.

A community of cultural involvement also led to The Ribbon’s success in Kansas. Kansans took personal responsibility for improving their community. Janet Bryant articulated this attitude and how it helped The Ribbon:

[Kansans are] just grassroots people … sometimes we’re more apt to pick up our heels and do something … In Kansas we think that things can happen; sometimes people get so cynical that there is no effort made, but I think in Kansas we still think, by golly, we can make things happen.85

Kansans’ belief in the power of personal action led the state community to embrace The Ribbon, despite the effort it required.

Evans noted how Kansans valued and sought out meaningful opportunities to participate: “I think as people saw it and heard about it; people thought they could be a part of it too.”86 Buller echoed the sentiment that the distinctive community ethic of Kansans helped the project’s participation: “I think Kansans are doers, and that we still feel a positive sense of community responsibility. We are neighborly.”87

Evidence suggests that Kansans were community participants at the time The Ribbon took place. Many Kansans who worked on The Ribbon were active in other civic organizations. Participants cited activity in numerous civic organizations and other community projects, both before and during their Ribbon experience.88 Ribbon participant Ethel Abrahams explained how her family often participated in several activities relating to peace: “Yes, in small communities like Hillsboro, people tend to be involved in many things. We participated in the church board, as deacons, in Sunday school, in peace walks, and solicited peace speakers for church events.”89

Evans also recalled a long history of participation in community-serving organizations: “I worked full-time doing church work for 25 years, including those during The Ribbon … before working on the Ribbon I had just completed four years as [Church Women’s Fellowship] state president.” The Ribbon required much of participants, but this was something Kansans, as community participants, were accustomed to. The format of The Ribbon provided Kansans with an outlet to enact their personal ethics, viewing the project as a way to positively impact community through personal action.90

Yet the ethic of community participation did more than simply recruit Kansas participants for the project. Community organizations in Kansas provided The Ribbon with a pre-existing structure through which Ribbon work was accomplished. Abrahams brought The Ribbon to her Sunday school class after attending an informational meeting about the project. One person was able to mobilize a large group of participants through an existing community organization: church. Abrahams recalled working on the project; only five members of her class “had a hands-on experience stitching The Ribbon.” Nevertheless, everyone her class contributed to the project in some way.91 Both Abrahams and the state coordinator for The Ribbon, Janet Bryant, recalled a high number of family groups working on The Ribbon together.92 93 The Ribbon was incorporated into the daily lives of participants.

Instead of forcing participants to go to meetings/gatherings outside their daily routines and social groups, the project was something that could be accomplished in social groups and settings that Kansans already regularly participated in. This helped Kansans view the project as relevant to their own lives. It also avoided the sense that the project was an extra burden beyond their typical social calendars. Bryant, for example, recalled making Ribbon segments in her women’s church group, an organization that met regularly before and after The Ribbon took place. Group members worked on their Ribbon segment during normally scheduled meeting times.94

When asked to contemplate what factors led to The Ribbon’s success, Evans recalled how important existing community groups were – church groups, schools, and clubs and civic organizations all contributed time The Ribbon.95 Community organizations throughout Kansas provided The Ribbon with a pre-existing network of participants and meeting times/locations to do Ribbon work. Ribbon organizers in Kansas recognized their state’s strength of community participation and took advantage of its existing resources to make the project a success.

Such effective leadership also contributed to success in Kansas. Abrahams recalled that in Kansas, “There were core committees actively concerned about and working on The Ribbon. It takes a few core people working hard to get the word out, and Kansas had people like that that were dedicated to this project.”96 Likewise, Bryant recalls the powerful leadership women in CWU provided The Ribbon in Kansas: Women who had leadership roles in CWU were powerful, they had moved up the ranks, and “they weren’t afraid of anything … they had this power, this charisma. … These women were powerful to me because they had fantastic leadership.”97

Aside from personal accounts, documents from the national Ribbon archives in Denton, Texas, suggest Kansas leadership was extraordinary: “We are doing great in Kansas ... I attended a Ribbon meeting in Topeka May 2 and was really happy to see such beautiful and well put-together ribbons. We are going to have way over the state’s quota of 40.”98 From the beginning, Evans was determined that the project would be well-organized: “I told the board, if we really started this, we weren’t going to just do a little bit, we were going to do this right.” In order to follow through with this commitment, Evans “planned a committee, [which] put a lot of effort into the project.” Evans was even “[concerned] with making the segments the same size, so they would fit together correctly” and responded by issuing standardized instructions about the size and specifications of ribbon segments.99 Clearly stated expectations and organization from the all-female leadership of The Ribbon in Kansas created a framework for success. This dedication produced results far above those of national Ribbon coordinators.

The Ribbon, as a project organized and dominated by women, related to women’s political activism. Some Kansas women entered the sphere of political activism for the first and last time through The Ribbon. Bryant, for example, engaged in other political action around the time of The Ribbon, but none since.100 This lack of political participation was not a result of apathy. Rather, it was the result of discontent with traditional methods of protest. Buller noted that The Ribbon “did not require marching in a protest demonstration or writing a letter to a congressman. But an individual could still make a powerful statement on what, in life and on this earth, is important.”101 Thus the form of The Ribbon, distinct from traditional forms of protest, encouraged Kansas women to get involved in politics for the first time.

In reality, Kansas women wanted to be heard. The Ribbon “was important to women, and it was a way for women to be visible too and to be heard.”102 Abrahams recalled how important it was for her to act for peace through her Ribbon experience: “It was an emotional experience … I still recall being at the Topeka Ribbon celebration. It was very encouraging to know I was not in the minority, instead there was a large group of people who cared about peace.”103 But what made The Ribbon so unusual? Why was it one of the only ways participants manifested their desire to speak out politically?

Many interview respondents justified their participation in The Ribbon as a family responsibility. Bryant explained that The Ribbon was a way for women to proclaim: “My family needs to live in a peaceful world.”104 Buller saw the project as a way to model “positive activism for [her] children.”105 However, women were not the only ones who were motivated by family responsibility to participate. As members of Tabor Mennonite Church’s Peace and Social Concerns Committee, both Kristin Schmidt and her husband Archie viewed The Ribbon as a “peace-teaching moment … to take hold of.”106 Norman and Ethel Abrahams equally participated in The Ribbon, often including their children in the process.107

However, male participation in Kansas could not rival the overwhelming number of Kansas women who participated in the project.108 Many participants were individual women who distinguished their work on The Ribbon from men’s work. Buller noted that “man-power” was needed to move and arrange Ribbon segments, but it was clearly her role to complete the family’s Ribbon segment and attend meetings for the project.109

Kansas women were comfortable with the form of The Ribbon and saw its political message as being transmitted through their sphere of influence: family. Evidence suggests that the Kansas women who participated in the Peace Ribbon Project viewed their involvement as a social obligation to care for society. Themes in Ribbon segments from Kansas suggest that life, particularly those of children, motivated women to protest against nuclear proliferation. In fact, many Kansas women involved their children in the Ribbon Project. Children helped their mothers make Ribbon segments by tracing their hands, signing their names, or drawing pictures of what they valued in the world.110 This reinforces the idea that Kansas women justified their participation in, and were motivated by, their roles as mothers or caretakers of society. The project encouraged Kansas women to take the step from community involvement to political activism.

This was exactly what Ribbon founder Merritt wanted. She sought a wider appeal for the project that would recruit participants outside of the traditional bounds of political action. The Ribbon sought to illustrate how its goals were applicable to all people:

There was an attempt to convince people that the nuclear arms race is an issue that affects people, regardless of gender, racial, ethnic, class, religious, age, or other differences. The project was presented to the public and the media as one in which many types of people could participate.111

While the project presented itself as welcoming to all kinds, it did not actively seek participation from minority groups: “On a few occasions Justine introduced the Ribbon specifically to women of color…But there was no systematic effort to reach or involve people of color.”112 Neither was there a concerted effort to recruit men, especially in Kansas.113 While men were not excluded from participation, the message of nuclear proliferation as something harmful to society specifically targeted women, –not just those accustomed to protest, but rather any woman who identified herself as being responsible for the wider society. From its beginning, this project intentionally targeted women participants.114

Kansas participation in the national Peace Ribbon Project was rooted in historical women’s activism that sought legitimacy through a “domestic sphere of influence.” Even male participants in Kansas justified their participation through obligation to their families. The non-threatening nature of The Ribbon, the format of The Ribbon, and the ability to focus participation on domestic issues like children and family all made The Ribbon appealing to Kansans (especially women) who felt comfortable participating in a project firmly tied to their domestic expertise. This is a main reason the project was successful in Kansas.

Kansans’ preoccupation with community involvement also contributed to participation and resources for the project. Civic groups and other organizations provided The Ribbon with a preexisting structure in which to find participants. And Kansas women, already prepared for leadership by other community service roles, established organization and clear standards necessary for the success of a large project.

Kansans were inspired by the ideas of The Ribbon, but that alone does not explain their participation. Kansans, particularly women, were drawn to the project’s unique form, viewing the project as a way to manifest their political concerns without breaking social barriers. The Ribbon’s design fit the values and strengths of Kansans, while local leadership delivered the project to Kansans and saw it through to successful completion.

1Linda Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon: Peace by Piecemakers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993), 33-39.

2New York Gazette June 17, 1986, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985, Basement, Woman’s Collection, Mary Evelyn Blagg-Huey Library, Texas Women’s University.

3Paul M. Cole and William J. Taylor, ed., The Nuclear Freeze Debate: Arms Control Issues for the 1980s (Boulder: Westview Press, 1983), 20-27.

4Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, 2008. http://www.americanforeignrelations.com/E-N/North-Atlantic-Treaty-Organization-Tension-d-tente-and-the-end-of-the-cold-war.html (accessed December 1, 2008).

5Ibid.

6Ibid.

7Cole and Taylor, The Nuclear Freeze Debate, 20-27.

8Deidre Rhys-Thomas, Letters for my Children: One Mother’s Quest for Answers about the Nuclear Arms Threat (London: Pandora Press, 1987).

9Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon: Peace by Piecemakers, 21.

10Helen Caldicott, Missile Envy: The Arms Race and Nuclear War (New York: Routledge, 1984).

11John Lofland, Polite Protestors: The American Peace Movement of the 1980s (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1993), 285.

12Ibid., 277.

13Harriet Hyman Alonso, Peace as a Women’s Issue: A History of the U.S. Movement for World Peace and Women’s Rights (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1993), 260.

14Lofland, Polite Protestors, 287.

15Amy Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace: traditional motherhood and radical politics in the 1980s (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1993), 222.

16Ibid., 278.

17Amy Swerdlow describes “women’s culture” as “not only the consciousness, moral values, relationships, and the networks of support among women that grow out of their maternal and domestic practice, but also … [as] ‘the ground upon which women stand in their resistance to patriarchy and their assertion of their own creativity in shaping society, in other words, the ways in which women, as a group, have historically re-defined and re-cast male-imposed roles and tasks on their own terms and from their own vantage point” (1993, 234).

18Ibid., 245.

19Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon, 33-39.

20Ibid., 114.

21Lofland, Polite Protestors, 281.

22The United Methodist Reporter, June 28, 1985, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, Woman’s Collection, Evelyn Huey-Blagg Library, Texas Woman’s University.

23Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon, 191.

24Ibid., 33-39.

25Ibid., 48.

26Julie Roy Jeffrey, “Permeable Boundaries: Abolitionist Women and Separate Spheres,” Journal of the Early Republic, 21 (Spring 2001): 79.

27Gerald R. Butters, Banned in Kansas: motion picture censorship 1915-1966 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), xii.

28Ibid., 269.

29Ibid.,174.

30Craig Miner, Kansas: A History of the Sunflower State, 1854-2000 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002), 224.

31Ibid., 128.

32Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace, 96.

33Alonso, Peace as a Women’s Issue, 12.

34Ibid., 11.

35Ibid., 11-12.

36Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon, 184.

37Ibid., 165-166.

38Church Women United in Kansas, The Story of the Kansas Ribbon: Kansans share a vision of hope, joy and peace (Wright, Kansas: EC Publicity, 1987), 13.

39Kansas Peace Ribbon Collection. Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, North Newton, Kansas.

40Justine Merritt, donor record, February 1986,The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, Woman’s Collection, Evelyn Huey-Blagg Library, Texas Woman’s University.

41Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon.

42New York Gazette, June 17, 1986, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985, Basement, Woman’s Collection, Mary Evelyn Blagg-Huey Library, Texas Women’s University.

43Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 4.

44Ibid., 71.

45Letter from Sister Jolene Farley to Mary Frances, May 27, 1984, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985, Basement, Woman’s Collection, Mary Evelyn Blagg-Huey Library, Texas Women’s University.

46Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 4.

47Ibid., 24.

48Church Women United “is a national ecumenical movement of Christian women witnessing to unity and faith in Jesus Christ through worship, study, action, and celebration … organized in December 1941.” Local units were organized in the 50 states. In Kansas, Church Women United was the organization that sponsored The Ribbon (1987, 3).

49Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 17.

50Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

51Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 17.

52Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

53Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 23.

54Fiberarts: The Magazine of Textiles May/June 1984 (51), The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985, Basement, Woman’s Collection, Mary Evelyn Blagg-Huey Library, Texas Women’s University.

55Church Women United in Kansas. The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 34.

56Ibid., 13.

57Ibid.

58Ibid.

59Ibid.

60Ibid., 16.

61Opal May Evans Peace Ribbon Collection, Kansas Christian Home, Newton, Ks

62Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, KS.

63Church Women United in Kansas, The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 17.

64Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, KS.

65Church Women United in Kansas, The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 17-20.

66Ibid.

67Ibid., 6.

68Ibid., 22.

69Ibid., 28.

70Robert J. Dole Archive & Special Collections, “Robert J. Dole Senate Papers (1968-1996),” Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics, http://www.doleinstitute.org/archives/senateseries.shtml.

71Church Women United in Kansas, The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 18.

72Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

73The Ribbon Questionnaire was a part of a study conducted by Texas Women’s University Department of Sociology in 1986, after The Ribbon was completed. Participants from around the country were asked to complete this questionnaire and, to the benefit of this research, were asked to identify what state they were from. The purpose of the study was to “learn more about the variety of people” who participated “and their reasons for doing so” (Miller).

74Miller and Cockrell, Ribbon Questionnaire, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985, Basement, Woman’s Collection, Mary Evelyn Blagg-Huey Library, Texas Women’s University.

75Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

76Christine Buller, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 3 December 2008.

77The Church Women United of Kansas, ed., The Story of the Kansas Ribbon, 50-52.

78Ibid.

79Ibid.

80Ibid., 10.

81Christine Buller, interview by Victoria Janzen, Hesston, Kansas, December 3, 2008.

82Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon, 87.

83Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

84Anita Bohn, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 3 August 2009.

85Janet Bryant, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 11 July 2009, Marion, Kansas.

86Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

87Christine Buller, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 3 December 2008.

88Miller and Cockrell Ribbon Questionnaire, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985.

89Ethel Abrahams, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 17 July 2009.

90Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

91Ethel Abrahams, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 17 July 2009.

92Ibid.

93Janet Bryant, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 11 July 2009, Marion, Kansas.

94Ibid.

95Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

96Ethel Abrahams, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 17 July 2009.

97Janet Bryant, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 11 July 2009, Marion, Kansas.

98Letter from Sister Jolene Farley to Mary Frances, May 27, 1984, The Ribbon: Ribbon Collection Records, 1981-1985, Basement, Woman’s Collection, Mary Evelyn Blagg-Huey Library, Texas Women’s University.

99Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

100Janet Bryant, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 11 July 2009, Marion, Kansas.

101Christine Buller, interviewed by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 3 December 2008.

102Janet Bryant, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 11 July 2009, Marion, Kansas.

103Ethel Abrahams, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 17 July 2009.

104Janet Bryant, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 11 July 2009, Marion, Kansas.

105Christine Buller, interviewed by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 3 December 2008.

106Kristin Schmidt, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 28 March 2010.

107Ethel Abrahams, interview by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 17 July 2009.

108Opal May Evans Peace Ribbon Collection, Kansas Christian Home, Newton, Kansas.

109Christine Buller, interviewed by Victoria Janzen, e-mail interview, 3 December 2008.

110Kansas Peace Ribbon Collection. Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, North Newton, Kansas.

111Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon,114

112Ibid., 117

113Opal May Evans, interview by Victoria Janzen, tape recording, 30 June 2009, Newton, Kansas.

114Pershing, The Ribbon Around the Pentagon, 33-39.