Calvin Redekop became intensely interested in Paraguay because of two personal friendships he formed at Goshen (Ind.) College: one with Willy Kaethler, a roommate from Paraguay who became a medical doctor in the Chaco; the other with Wilmar Stahl, a student assistant at the college who later led ASCIM, an Indian settlement program in Paraguay. Redekop spent 1971-72 researching Indian settlement, and has written about Paraguay and visited the country numerous times, most recently in January 2010. The development of Redekop’s article was funded in part by the Kansas Humanities Council, a nonprofit cultural organization promoting understanding of the history, traditions, and ideas that shape our lives and build community.

Paraguay (Guaraní for “a place with a great river”) has long been perceived as exotic, mysterious and utopian – a perfect terra incognita, a romantic country with exotic flora such as the bottle tree (palo borracho, drunken tree), enchanting fauna from the ostrich to the boa constrictor, cattle rustling gauchos and beautiful women. Thus it was that Elisabeth Nietzsche (sister of Friedrich) and her husband Bernhard Förster decided that “Paraguay was to be the setting for the most glorious moment of their lives, the culmination of a dream no less grandiose and hopeless than the one which had inspired the dictator López to model himself on Napoleon.”1 All these romanticized images derive basically from many amazing aspects of Paraguayan geography, history and peoples. This perspective continues to attract tourists, investors and do-gooders to this day. Macintyre concludes that very few have been able to give a realistic account of Paraguay and today “the situation has only marginally improved.”2

However, those better acquainted with Paraguay know its history includes some of the most intractable and tragic aspects and realities of the human struggle. For the aborigines, the original denizens, Paraguay demanded continuing adjustment and accommodation as they dealt with constant invasions. For the conquerors from Spain, Paraguay served as the staging platform in the search for el dorado, the land of gold (they failed miserably, dying by the thousands in the Chaco; the survivors ended up “settling in” and marrying Guaraní women). For the many settlers/colonizers, Paraguay provided almost unlimited freedom to pursue their dreams.

In the process of developing into a sovereign nation, Paraguay became involved in the War of the Triple Alliance (1865-1870), in which the country lost more than a third of its population.3 The equally brutal War with Bolivia (1932-1935) devastated Paraguay. All along, people came to Paraguay in large numbers to pursue their “utopian dreams.” All these contributed to internal conflicts, including displacement of indigenous peoples and even alleged genocide.4 These briefly reviewed events produced a narrative that created painful and divergent, tragic memories for the three major Paraguayan people groups (see Table 1).

These tangled events have diverted the peoples of Paraguay from achieving their goals, relative to each other as groups of citizens as well as in national terms. The major focus in this lecture is the tragic fate of “indigenous peoples” (the original native residents) in confrontation with two other dominant value systems and societies – “the Paraguayans” and the many foreign immigrant groups I will call “settlers/colonizers.” This lecture will deal specifically with serious confrontations during the 1970s and conclude with a personal proposal of what might be done to allow the indígenas of Paraguay to craft their own future along with the other two societies.

A. Early indigenous history

There are several views of Paraguay’s pre-colonial period. The most general is that “Indian tribes speaking the Guaraní language occupied the region between Paraguay and Paraná rivers long before the arrival of Europeans.”5 This Guaraní tribe derived from a larger Tupian language stock. Later analyses of Paraguayan history assume this oversimplified perspective and ignore west Paraguay, or the Chaco. Another view, while not denying the dominant role of the Guaraní in east Paraguay, maintains that populations in east Paraguay as well as the Chaco stem from a much more complex convergence of other tribes than is normally assumed: “Since pre-Columbian times, the Gran Chaco has been inhabited by peoples characterized by a nomadic or seminomadic economy based upon hunting, fishing, gathering and seasonal horticulture.”6

|

Thus Paraguay in pre-Columbian times consisted of a variety of indigenous populations subsumed under six different language families: (1) Matac-Mataguayo; (2) Guaycuro; (3) Maskoy; (4) Zamuco; (5) Lule-Vilela; and (6) Tupi-Guaraní. This latter category is more directly related to the east Paraguayan Guaraní as well as the Chaco. After the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, the Paraguayan area became a sanctuary for many Amerindian groups trying to escape foreign incursions and hegemony.7 The interpenetration of the Guaraní and Chaco tribes is much more complex and important than has generally been known. Chase-Sardi has provided an extensive catalog of Paraguayan indigenous tribes and lists 18 different tribes, distributed in an astonishing 164 different settlements.8

B. The Spanish-indigenous amalgamation--the mestizo or “the Paraguayans”

Most accounts of Paraguay begin with the Spanish conquistadores, or invaders, who were looking for a shortcut to the reputed Inca realm of gold – el dorado. Failing to find it, they settled in the Asunción region and established a colonial southeastern power outpost under Domingo Martenis Irala (1536-1556). Originally, the Spanish employed the Guaraní as manual labor for economic development. President Irala encouraged Spanish intermarriage with Guaraní women and slowly developed the Paraguayan society and culture into an amalgam of Spanish and Guaraní culture, now normally referred to as a mestizo ethnic population. In this context, we refer to the mestizo as the “Paraguayan people.”9

The Jesuit reducciones, an astonishing development, arrived soon after the conquistadores. They were sponsored by the Spanish Crown along with a special mandate from the Roman Catholic Church. Beginning in 1547 and numbering 33 reducciones at its peak, this Jesuit movement developed a miniature “church/state” within a developing nation. Working in cooperation with the Guaraní and other native groups, the Jesuits established a self-supporting “empire,” including a full religious institutional system, a self-sustaining economy, a political order and even a military structure.

Thus an integrated mutual society developed, consisting of indigenous tribes and “foreign invaders,” that was far ahead of its time. But this utopian movement became so successful, powerful and ultimately threatening to Spain and Brazil that it was disbanded in 1767 as the result of the Church’s withdrawal of their mandate and the military assault of combined Spanish-Portuguese forces.10 The social and cultural achievements were destroyed and all the material and economic achievements absorbed into Spanish landed estates or otherwise cannibalized, leaving the aboriginal people more impoverished than ever.

C. The invasion of other nationality groups – the settlers/colonizers

The expulsion of the utopian Jesuit experiment from Paraguay in 1767 clearly must have impressed itself on the memory of other opportunistic dreamers, though it took some time for this “utopian experiment” to sink in. But sink in it did. Among the earliest organized immigrations, with permission from the emerging Paraguay government, was one begun in 1855, consisting of a French group that settled at Villa Hayes, northwest of Asunción, and called itself Nueva Bordeos. It had vague utopian goals, but was soon disbanded.11

The next group, consisting of German settlers, some of whom had proven their courage and military competence in the tri-partite war, was invited to settle and help develop Paraguay by the government, which paid travel expenses, gave free land and provided all necessary technical help. This settlement, established in 1871, lasted only a few years because of internal conflict and lack of structure.12 A similar settlement was established in 1874 near Ita with approximately 1,000 English and some Germans. It too lasted only a few years.

|

The Germans continued to be enthralled by Paraguayan utopian possibilities. In 1881, a number of families from Berlin and Hamburg established an agricultural settlement near San Bernardino, after which the colony was named, near beautiful Lake Ipacaray. They built a health resort that aided in their survival when it became well known internationally. Their main livelihood, however, came from garden produce and agricultural production. A daughter colony, Altos, was established near San Bernardino in 1883 and became prosperous through production of coffee, grapes, milk and meats.13

Nueva Germania, established in 1887 by Bernhard and Elisabeth Förster some 80 kilometers from the Paraguay River and 100 kilometers north of Asunción, was based on utopian motives. Bernhard Förster died two years later, but Fritz Neuman, from Breslau, accepted leadership and the community developed and commercialized yerba, which eventually resulted in maté or tereré becoming the national drink, which continues to the present day. This experimental community, which “would be the nucleus for a glorious new Fatherland [which] would one day cover the entire continent,” is one of the most bizarre in Paraguay if not South America.14 A remnant of the original community still survives.

At the turn of the century, German settlers established Hohenau, a base in heavily wooded east Paraguay. The government assisted the group in settling on 30,000 hectares of land. Hohenau became very prosperous, producing yerba, sugar cane, hogs, dairy products and beer. This very successful settlement spawned daughter colonies in Capitán Maza, Obligado, Bella Vista, Jesús Trinidad, Cambyreta, San Miguel de Curuso and Alborada, all with their own varieties of agricultural products.15 Other German and Brazilian settlers founded colonies near Incarnación, Independencia, Carlos Pfannl, Sudetia, Villa Rica, Chingui Loma, Rosario Loma, Antequera, Barranquita, Concepción, Horqueta, Neuhoffnung, Villeta, Canadita and Elisa, as well as in Asunción, an attempt to establish a German colony in an urban setting.

One Italian settlement, Nueva Italia, was founded in 1906 and another, composed of Poles and Russians, in 1927. These two colonies did not survive.

Recent colonization efforts in Paraguay that both survived and expanded dramatically include those of the Mennonite-denominated groups. In December 1926, 1,700 conservative Mennonites from Manitoba and Saskatchewan landed at Puerto Casado in west Paraguay and established a settlement. They bought a huge tract of land from the Casado Company that ultimately totaled some 843,206 acres.16 The Mennonites decided to settle only after the Paraguayan government accorded them special privileges, contained in Ley 514, exempting them from many duties, including military service and certain taxes.

A subsequent colonization occurred in 1930 with the arrival of a group of 1,500 Mennonites who had left the Ukraine after World War I, the Communist revolution and terrible drought. They were given the same status under Ley 514 that the earlier group had received, and expanded the beachhead in the Chaco. They bought 40,000 acres from the Casado Corporation and established Fernheim, now a thriving colony. Fernheim has purchased additional adjoining land through the years.

In 1937, because of early hardships in the Chaco, a group of 748 Fernheimers left the colony to establish a settlement east of the Paraguay River, where climate conditions were more favorable. Then in 1947, another group of 2,400 Mennonites from the Soviet Union were able to immigrate to the Chaco, where they built the colony of Neuland. Again, a dissatisfied group numbering around 1,800 refused to settle in the Chaco and established a colony at Volendam near Friesland colony. This colony experienced considerable turmoil and emigration but has survived.

Through contacts with Mennonites and with help from Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), the Society of Brothers received permission from the Paraguayan government to buy 20,000 acres near the Friesland colony in 1940. This colony did not succeed, however, and the Friesland colony later purchased the land. More Mennonites, numbering 1,700, arrived in east Paraguay in 1946 – the Bergthal and Sommerfeld group in the Caaguazú region. Relatively prosperous, they bought 108,640 acres of land and, even with some emigration, have rapidly expanded their populations.17 Since 1948, an expanding stream of conservative Mennonite groups that wish to remain separate from the world have settled in east Paraguay. This stream totals at least 12 groups, coming from Canada, Mexico, Belize and the United States.18

This brief survey, though not exhaustive, provides a general overview of the three main populations that have existed in the same terrain – the original tribes, the so-called “Paraguayan” mestizo sector and the colonizers/settlers, including missionaries.19 The interrelations between these groups should and can be viewed from the perspectives of the three groups, to which we now turn.20 This discussion cannot include all the smaller utopian or colonizing ventures listed above (see Table 2 for a listing of major groups).

In order to find a theoretical basis from which to analyze the present and to derive some possible resolutions to the Paraguayan “malaise,” it is necessary to analyze the consequences of the presence of the three major populations described above and their understandings of each other’s way of life.

A. The Paraguayan perspective

The “official” Paraguayan perspective regarding the presence of the other two groups, based on the “official” and the general policies as they were enacted, can be generally stated as follows:21

1. Regarding the aboriginal/indigenous population, the policy has varied among grudging neglect, toleration, grudging recognition on the positive side, and exploitation, displacement, hostility and even genocide, depending on the regime in power. Bartomeu Melia, S.J., has maintained that “The indios have no illusion regarding the ‘dream.’ During the four and a quarter centuries of the Colonia the indios have not received a single benefit from the invaders [from the first Spanish], nor have they received them [the indios]. However with much dignity, many among them have died as they strove to protect their dream of self identity.”22 This may seem harsh, but supports the general stance of “official” Paraguayan policy over the centuries, especially in during the Stroessner regime.

In recent times, however, international awareness aided by modern communication has increased global knowledge and outrage. One example among a host of others is “Behind Closed Borders: Paraguay’s Use of Torture and Repression.” Describing President Stroessner as “a throwback to the nineteenth-century caudillo,” Penny Lernoux deals not only with the exploitation of the “Guaraní peasants” but the “thousands of political prisoners…held for months or years without official trial.”23 “Every time a movement gathers strength, the government suddenly discovers a ‘communist conspiracy’ sending in troops to destroy the rural farm cooperative, burn the peasant’s huts and crops, rape the women, and kill or imprison the men.” She continues, “The Right Reverend Anibal Maricevich, Catholic bishop of Conception, reports that on many ranches the peasant has ‘less value than a horse or a cow.’” She reports: “Wealthy Paraguayans are generally indignant that the peasants are mistreated. ‘They’re just dirty animals,’ exclaimed the wife of a large rancher.”24

The “official policy” has, however, been undergoing a general evolutionary process that now recognizes existence of the indígenas, provides them with citizenship and, in the revised constitutions, the right to vote, the right to strike and freedom of religion.25 In spite of these official freedoms, the practical consequence has basically been benign neglect. In addition, there has often been harassment and expulsion from native lands because of government actions to provide land to recent immigrants, as well as for other reasons. A recent example was expulsion of Indians to make way for the huge Itaipu hydroelectric plant.26 In recent decades, the political parties have begun to see the importance of the indigenous vote and have begun inviting them to participate in elections.27

2. The Paraguayan policy regarding foreign settlers and colonizers contrasts dramatically with that of the policy on aborigines/indígenas. Almost all groups of settlers/colonizers have been invited by, and given extensive assistance from, the Paraguayan government to help “develop” the country or they were, at least, allowed to purchase land in order to pursue their own goals, based on the assumption these goals would contribute to the development of the country. Fretz maintains that immigration over the past centuries has been strongly encouraged by the Paraguayan government. As a result, “By 1925, it is estimated that there were between thirty and forty thousand inhabitants of Italian, Argentina, Brazilian, German, English, Spanish, and French origins in Paraguay.” By 1958, Fretz estimates, there were more than 66,000 registered immigrants but, he adds, “It must be stated repeatedly that these figures have no known relations to the actual total of immigrants” because of loosely guarded borders.28

B. The perception of the settlers/colonizers29

|

Though varying by time, place and group involved, the settlers/colonizers’ position toward and perception of the indígenas has been mainly enclavic separation, avoidance or neglect, but most commonly utilizing the indígenas as labor when convenient. Settlers/colonizers have not been aggressive in supporting the indígenas in their internal social/economic development or in advocating for them in relations with the state. “Benign neglect” of the indígenas is probably the most tangible and persisting relationship. One glaring example is the settlers/colonizers’ failure to help the indígenas become registered with the federal government, without which many of the theoretical rights granted in the constitutions are not in effect.30

There are almost no cases of settlers/colonizers integrating Indians on the land the “invaders” have occupied and developed. Further, there are few cases of cooperative ventures designed to include the natives. The general consequence has been that settlers/colonizers have continued to prosper within their colony boundaries and have continued to buy up more land for expansion with the permission or even positive official support from the Paraguayan government, including forcible expulsion of indígenas from traditional lands.31

One of the few exceptions is the Mennonite settlement in Paraguay, beginning in 1926, built on an agreement with the Paraguayan government defined in Ley 514 that gave them an unusual special set of rights.32 The Paraguayan government designated huge amounts of land for purchase without disclosing that this land was the traditional home of many Indian tribes. Only after the Mennonites were hacking out an existence in the inhospitable Chaco and later in east Paraguay did the reality of a native presence already there sink in.

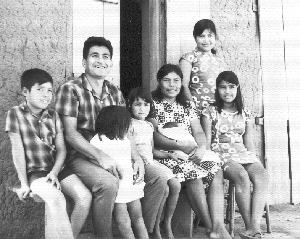

The first response of the Mennonite colonists to their newly discovered “neighbors” was evangelization and mission, beginning in 1936, but this was seen very early as not solving food, shelter and basic survival issues. The colonists soon instituted an “Indian Settlement” program. The Mennonite colonies, assisted by MCC and later Mennonite Economic Development Associates (MEDA), eventually purchased a total of 42 leguas of land (78,750 hectares or 194,125 acres) that was set aside for a long-term Indian settlement and development program. In general, this has been a successful venture, even in the face of all the culturally based misunderstanding, both on the part of indígenas and the Paraguayans. This is possibly one of the most unusual mutual settlement programs in the history of Paraguay, reminiscent of the Jesuit reduccionnes.33

One leader realistically expressed the Mennonite perception of the “Indian problem”: “I think the self-determination of the Indian will take at least a hundred years. To expect the Indian to change rapidly is unrealistic. His mental process just can’t make the change. They want our way of life, but not really. We build them nice new houses, and what do they do, they sleep outside in the cold. An Indian must be told a hundred times before it finally sinks in.”34

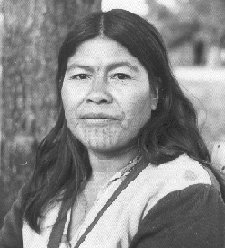

C. The perception of the two other groups by indígenas

The indígenas’ perception and attitudes toward the other two major populations is at the same time simple and complex. Perception of the state is simple in that indígenas have had little contact with the state and what contact there has been is largely hostile on the part of the state. Less simple is the indígenas’ desire to be given freedom to live their own lives, even though they are becoming more integrated due to dependence on wage income for their own survival.35

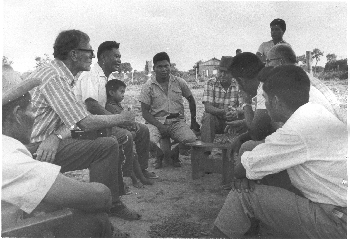

Perceptions of the indígenas toward the settlers/colonizers are more complex. One anecdote must illustrate, since so few objective records of indigenous attitudes exist. In 1971-72, the author interviewed members of numerous groups of Indians in the Chaco on their main disappointments with and complaints about the “white man.” The most frequent complaint was that the indígenas had so little land. Next was concern that they were not getting paid enough for work they did for the Mennonites. Third was the wish for more assistance to live independently on the land.

One interview illustrates: “An Indian said, ‘We need more land. With two horses, too much land is taken up just feeding them.’ To which a leader replied, ‘We don’t need more land, we don’t even watch the land we have – look at all the unworked land and all the weeds. I am a preacher and I have to spend most of my time urging you to stay at home and tend to your work.’”36 They also lamented that they were not being afforded a more comfortable existence, through access to more and better food, better clothing and more security against famine.37 This was questioned by a Lengua leader: “The young people don’t want to help work on the chacra. They would rather mingle with the Mennonites in town. They want to eat, live and wear clothing like the Mennonites. They cannot see why they should work on the land – it takes so long before food comes. In the towns, they can work and get paid immediately. ”38

I will now analyze the juxtaposition of these three non-commensurate worldviews in the context of the coming of the South American “liberation movement.” The struggle between indigenous and the “established” societies and countries began from one end of Latin America to the other in the mid-1960s, given special urgency and impetus by Pope John XXIII’s Second Vatican Council, that began in 1962.

Pope John wished the Second Vatican Council “to increase the fervor and energy of Catholics, to serve the needs of Christian people.” To achieve this end, bishops and priests must grow in holiness; the laity must be given effective instruction in Christian faith and morals; adequate provision must be made for the education of children; Christian social activity must increase; and all Christians must have missionary hearts. He was able to express his desire in one Italian word, Aggiornamento – the Church must be brought up to date and must adapt itself to meet the challenging conditions of modern times.39

Since Latin America at the time was predominantly Roman Catholic, this Second Vatican Council accentuated the urgency of “conscientization” in this region. Even though some actions in this direction had already begun to be implemented by the Roman Catholic church and priesthood, as a result of the global ferment beginning in the 1960s, Vatican II sparked new emphases in theory (theology), practice and organization: a from-the-bottom-up movement over against hierarchical structures; orthopraxy over orthodoxy; a “preferential option for the poor,” Christian base communities, lay participation in church leadership, landless worker movements, and so on. The priests and orders in the Paraguayan church were not immune to this new movement.40

By the late 1960s, Miguel Chase-Sardi, S.J., a Paraguayan anthropologist, had compiled an extensive and copiously documented account of the situation of the indigenous tribes in Paraguay, entitled La Situación Actual de los Indígenas en el Paraguay.41 Supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship, Chase-Sardi directed a massive study of all the tribes currently existing in Paraguay. The description and analysis followed four rubrics: 1) identification of the tribe, 2) general location, 3) estimated demographics and 4) economic situation. This review is a major source for understanding the indígenas’ present existence. Chase-Sardi used available published material, but with his team also personally visited many of the tribal communities, including the Mennonite-sponsored settlements in the Chaco.42

|

His reporting, though generally very valuable, was tilted toward the indigenous tribes in many respects, leveling criticisms on many of the “invaders/colonizers.” Thus, for example, he sharply criticized the Mennonite colonies for almost totally disrupting the indígenas’ former hunting and gathering life, including taking away land, fencing land so the indígenas could not allow their sheep or cattle free range, and not providing adequate employment (or grossly exploiting the indígenas when they did). Chase-Sardi provides copious figures on wages paid to Chulupi and Lengua workers, one half that paid to Mennonites for the same work. Chase-Sardi writes, “We can affirm that the Mennonites have joined Mohammed in saying ‘Believe, or die of hunger.’”43

Chase-Sardi reported the results of his research at the 1971 Barbados Conference in Bridgetown, Barbados. Chase-Sardi’s research obviously provided ammunition for the conclusions of the Barbados Conference. As indicated above, Chase-Sardi documents the conditions of the 17 major tribes, including factors such as means of livelihood, employment in neighboring settlements/colonies, relationships with government departments, and so on.

Among the most important of the emphases and actions that emerged from this conference was the “Barbados Declaration,” issued Jan. 30, 1971, the last day of the conference. Signed by a number of anthropologists and priests from North and South America who attended the meeting, the declaration was presented in the hope that “it would make a contribution to the grave continental situation [regarding the Indian situation] and the struggle for liberation on the part of the indígenas. The American indígenas continue to be subject to a colonial domination which obtained from the moment of conquest, and which has not changed.”44

The Barbados Declaration presents a scathing denunciation of the policies and practices of Latin American countries regarding the indígenas, including: ignoring them; forcible displacement; exploitation; military harassment; and, most pointedly, genocide. It presents a list of demands for change: A) Responsibilities of the States/Nations (seven issues); B) Responsibilities of the Religious Missions (four issues)45; and C) Responsibilities of Anthropologists (five issues). Interestingly, it includes no critique of the many immigrant/colonization groups that had existed for centuries up to the present, many of which had direct relationships with indígenas and could have been included in the declaration’s Demand A.

This conference reflected a growing concern created by the larger liberation movement in Latin America. Countless conferences, directives, studies and declarations were issued during this time, all rejecting and condemning injustices toward the indígenas. The claims of genocide produced the greatest uproar. Many secular newspapers and magazines as well as religious and church publications protested loudly and demanded action. The most radical declared that mission organizations should terminate their work since it destroyed the basic core of indigenous culture and selfhood.

One example is a New York Times report by Jonathan Kandell, “Slavery Just one Threat Facing Paraguay Tribe.”46 “Until less than two years ago the members of the Ache tribe were the victims of man-hunters intent on slaughtering them, enslaving their infants [sic] or forcing them onto reservations. Examples of slavery abound even today in eastern Paraguay, and occasionally in the capital.”47 During these decades, Alfredo Stroessner, a ferocious and consummate dictator, ruled Paraguay. The treatment of the indígenas included displacement and alleged genocide. The report states: In June 1973, the University of Bern released an open letter to the Paraguayan government which charged that “carefully organized massacres of Aché Indians (otherwise known as Guayaki of the Tupi linguistic stock) added to the detention of Aché Indians in ‘reservations’ indistinguishable from Nazi concentration camps and calculated to insure physical and psychological collapse had taken on genocidal proportions and had been carried on with the apparent approval and indeed connivance of the Paraguayan governmental agencies.”48

The public frustration and anger that Chase-Sardi and other anthropologists aroused regarding alleged aggressive tactics in Paraguay soon resulted in public discussion and demands for action. The global religious world also became involved. In one response, Rev. Heinold Fast, a German Mennonite pastor, and Domini de Zeeuw, a Dutch Mennonite leader, concerned about the negative report on Mennonite treatment of the Indians in the press, wrote to the World Council of Church’s “Commission on the Program to Combat Racism” secretary, Baldwin Sjollema, asking for clarifications of the “facts.” Sjollema replied: “Several of the serious criticisms in the report have been taken up by a WCC sponsored special consultation of Missionaries, Indians and Anthropologists.” After further extensive discussion, he concluded: “Last but not least, I should say that much of the criticism addressed to the churches and missions in the report is what the Indians feel. Surely, if injustice is done to persons or missions, these should be corrected.”49

In the meantime Chase-Sardi continued his attack, especially on the Mennonites, allegedly partly because he had been unwelcome during his visits to the Indian settlements which the Mennonite colonies had sponsored since 1936. “I have spent two or three months each year residing in the zone of the Mennonite Colonies or on their border, and exactly 45 days ago I was in serious difficulties because the Mennonites refused to sell me gasoline, oil, food and water.”50 In the increasing counter incriminations Chase-Sardi claimed that the Mennonites had misused German development funds, some of which were to have been used for Indian development and stated that the Mennonite Colony administration were refused a German Government development credit “because the Mennonites did not consent to the control that it was desired to place on the form of their investment.”51

The Mennonites were extremely upset by these accusations and engaged an outside expert, who had earlier done extensive research on the Mennonite settlements, to review them. He found no evidence to support Chase-Sardi’s claims and concluded his report in the Mennoblatt: “The [Chase-Sardi] description is very one-sided ….”52 Other reactions included a rejoinder to Sjollema by Dr. Jacob A. Loewen, an anthropologist who had done considerable field work in the Mennonite mission work in the Chaco: “I find it very interesting that you say your report expresses what Indians feel and say, but you quote Dr. Sardi who is by no means an Indian. Furthermore, it may be of interest for you to know that there are two competing groups in Paraguay trying to serve Indian interests, and they often vie for making the kind of statement that has been printed in your book. Personally, I feel correspondence with Dr. Sardi is going to help you very little. What needs to be done is some investigations on the spot with other sources, and then public retraction of what has been printed in the World Council’s name.”53

Anthropologists became more intensely involved in this dialogue and began actively discussing this situation because of strong public demand that they “do something.” Reflecting the anthropology community’s position, David Maybury-Lewis responded in an article entitled “Don’t put the Blame on Anthropologists.”54 He proposed that anthropologists do not get directly involved because “the very presence and activity of anthropologists…could by itself produce changes and disruptions of the sort that would normally be deplored [such as for example] being the handmaiden of colonialism.” He did, however, agree that anthropologists probably have not done as much as they could.55

These episodes during the mid-1970s point to a wide and agitated response regarding the racism, oppression and even genocide alleged to be taking place not only in Paraguay but also in the rest of Latin America. Public response tended to ebb as the situation in each region was investigated and “adjusted” in its specific way. But because of the negative press Paraguay had been getting already in the early 1970s, and also to protect the Mennonites colonizers,56 the dictator Stroessner took action to “squelch” a major source of the discord by incarcerating Chase-Sardi and torturing him. “In December of 1975, as well as in January and February of 1976, the International League for the Rights of Man received information that those arrested (Chase-Sardi and his senior staff at the Catholic University of Asunción) had been tortured. Dr. Chase-Sardi was initially drugged, beaten and subjected to submersion in water. He suffered a broken rib, could not use his arms. These reports come from unimpeachable sources directly on the scene whose names cannot be revealed for fear of reprisal.”57

Outraged global human rights organizations continued to press the Stroessner administration for Chase-Sardi’s release, and their efforts were ultimately successful. But those closest to Chase-Sardi say he was “a broken man” and lost most of his physical and spiritual energy and commitment to help the marginalized Paraguayan tribes. Thus Paraguay lost one of its most courageous and single-minded defenders of the weak and marginalized.58

|

In the meantime, individuals and anthropologists had also become increasingly involved and concerned about the veracity of the Chase-Sardi reports. The relatively uncritical acceptance by anthropologists of the various reports resulted in an exchange by the author in an article in the March 1976 issue of American Anthropologist entitled “Anthropologists and Anthropological Reporting.” I reviewed some examples of false or exaggerated claims made by Chase-Sardi of situations with which I was acquainted and called for more careful analysis of the emotionally loaded issues of exploitation, harassment, torture and genocide variously reported in the press and academic journals.

Thus the heated debate continued, especially in Paraguay. Numerous North American anthropologists invited Chase-Sardi to speak on their campuses – including Bethel College and Wichita State University – to analyze and evaluate the overall situation. He met invited guests at “an informal dinner meeting in the private dining room at Bethel College, Tuesday, April 26, 1977.”59 Earlier, Chase-Sardi attended an international symposium on “The Impact of National Development on the Indians of Tropical South America,” sponsored by the University of Wisconsin, April 22-23, 1977. Program presenters included Chase-Sardi, Maybury-Lewis, Elmer Miller, Robert J. Smith, Arnold Strickon, Charles Wagley and the author, among others.60Chase-Sardi presented the conference keynote lecture, entitled “Towards Indigenous Self-Determination: An Experience in Applied Anthropology.” The thrust of his presentation centered on the need for anthropologists to become more active in helping indigenous tribes retain their own history, identity and integrity and shape their own future. The conference seemed to have “lowered the temperature” on all sides, probably reflecting Maybury-Lewis’ “Don’t blame the anthropologists.”

The intensely harsh unilateral and secret nature of repression in Paraguay of minority groups and of critiques of government policy largely ended with the fall of the Stroessner regime. But issues concerning indigenous human rights, as well as their progress in pursuing their own vision and peoplehood, remained largely unsolved and continued to become more active.61 The recent national election campaign was unusually aggressive in appealing to the indigenous populations. All parties made extravagant promises of improvement in health services, police protection, economic assistance and education. The Patriotic Alliance for Change party won but has apparently failed to carry out its promises, since sporadic strikes and incidents of protest groups barricading major roads continue.62

It is safe to say that the indigenous population’s restiveness is increasing and that unless adequate change comes soon, the Paraguayan government, the Paraguayan people and the settlers/colonizers will see more violent actions from the indígenas. Nevertheless, a solution to the situation that will avoid more tension and, even more, violence and counter-violence, must be attempted. To this end, I propose a thesis that may point in third direction:

Paraguay’s history reflects the “throwing together” of three peoples whose cultural histories and value systems are so divergent that there has been little attempt at achieving a national common identity. Such a common identity or “ethos” can only emerge if the three value systems are brought into dialogue and begin to produce some kind of common national charter respecting the divergent goals of the three peoples.

This thesis is based on several background factors:

What changes must be made before a national common ethos or charter can emerge that will provide for a common social, economic and political future, yet which will provide respect and freedom for all the incommensurate groups living in Paraguay?

A second option is for concerned citizens in Paraguay to consciously participate in the national reconciliation. This requires: 1) All Paraguayans to become more consciously open to and aware of each group’s values, beliefs goals and aspirations, so that “victimization” of the less capable or “less developed” group, whether intentional or not, will not continue; 2) formulation of a solution to the problem that is agreed to by all three groups; and 3) implementation of such a national plan. But it is my opinion that neither the Paraguayan mestizo people’s political and religious establishment, nor any of the many powerful immigrant settlement/colonizers and the missionary groups,70 nor the indigenous peoples, will be able to bring this reconciliation to pass in the near future.

I make several practical observations, which though by no means definitive, may offer an idea of what may be a hopeful and promising way of the future.

The first example of such programs is the massive “Indian settlement” work that Chaco Mennonites, with the help of North Americans via MCC, have completed. In spite of Chase-Sardi and other critics alluded to above, I think it is safe to say that there is no other example in Paraguay where as many Indians have been given hope for a better life. Around 6,713 Indians have been helped to become self sufficient and autonomous.74 This huge enterprise is not free of problems or conflict and misunderstandings, and I have personally criticized some aspects of the program.

The second example is even more recent and specific. The Paraguayan chapter of MEDA has within the last decade created a microenterprise program in Paraguay that provides cooperative projects whereby Indians become part of planning, execution and benefits (employment, profits and management). One example is the charcoal industry that has been established in the Chaco near Filadelfia. The company, DIRSSA, with MEDA’s assistance, has been organized to produce charcoal for sale in Germany. Indigenous, Paraguayan and Mennonite farmers gather and harvest the wood, burn it in their own charcoal ovens on their own chacras to produce charcoal pieces, and transport the charcoal to the plant. The work is dusty and dirty but indigenous partners are pleased with the project, producing 27 percent of the output last year.75

It is my belief that this kind of cooperation between indigenous, Paraguayans and settlers/colonizers (e.g., the Mennonites), with the enthusiastic approval and support of the national government, is probably the most concrete way by which the indigenous can become true partners with the other two dominant constituencies in Paraguay. A cooperative nation can in this way emerge that will contribute to economic, social and political equality and justice for all. For example, the Indians involved in microenterprises are becoming more interested in registering with the federal government via the governmental Indian agency (INDI), seeing the importance of that status as they become more integrated into the larger society.76

“Prophetic modeling,” with adequate opportunities for imitation and participation, can be the best method whereby actual economic and living conditions of the most deprived section of the Paraguayan population, the indígenas, can be achieved. Good news travels fast, and invites imitation. I propose that the “modernization of Paraguay” is beginning to gain momentum, especially with political democratization taking root, and now is the time for morally sensitive organizations to more consciously join in the effort.

Paraguayan national history began with the Jesuits’ utopian vision that deeply involved the original denizens of Paraguayan lands, though it meant basically adapting to a European plan. But it was a vision and a beginning for indígenas to partner and participate in pursuing a better life. In order for Paraguay to continue in that utopian vision, the country needs help to birth an authentic peoplehood, however that is defined for each group. Paraguay alone must decide what peoplehood will look like. The age of domination by one sector of a society is over. History tells us that interested and informed bystanders can and must lend a hand only when requested, not impose on the natives, as was the case with the Jesuit utopian vision.77

1Ben Macintyre. Forgotten Fatherland: The Search for Elisabeth Nietzsche (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1992).

2Ibid., 2. A personal note: I have been also been attracted to Paraguay by its “mystique,” returning often.

3The war cost Paraguay 450,000 dead. It is estimated the war left only 20,000 living males in all of Paraguay. John Hoyt Williams, “Paraguay,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 432.

4There are many sources detailing the plight of indigenous peoples. One is Cultural Survival Inc., which publishes a Newsletter. See, for example, Volume 5, No. 1, Winter 1981, which includes data on the Chaco.

5Williams, 431.

6Elmer Miller, ed., Peoples of the Gran Chaco (Westport, Conn.: Bergin and Garvey, 2001), p. 1. The standard source on indigenous peoples for Latin America is. J. Steward, ed., The Handbook of South American Indians (Washington. D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, 1946). The geographical placement of the tribes deriving from these groupings historically and contemporarily are extensively described by Miguel Chase-Sardi, La situación actual de los indígenas del Paraguay (Asunción: Centro de los Estúdios Antropológicos, Universidad Católica, 1972).

7Miller, 1.

8Chase-Sardi, 80-104. This may seem improbable, but the author has visited at least a dozen on the list attesting to the accuracy of this tabulation.

9However this mestizo population has been socially and economically divided into an extremely wealthy and powerful small elite with a large middle class and a poor class. The top 10 percent controls 43 percent of the income.

10Williams, 431. See also the extensive article “Jesuit Reductions” in the Catholic Encyclopedia. The Jesuit success in assisting the Guaraní to become economically and socially self-supporting is a remarkable historical achievement that still influences the political, social and economic values in Paraguay.

11Gerhard Ratzlaff, Ein Leib - viele Glieder (Asunción: AEMP, 2001), 13.

12Ibid., 13.

13For extensive accounts of many of these settlements, see J. Winfield Fretz, Immigrant Group Settlements in Paraguay (Newton, Kan.: Bethel College, 1962), 52-53. Fretz does not deal with the indigenous presence since this would have complicated the research immensely.

14Macintyre, 3. Elisabeth was given a life stipend by Hitler for establishing an "ideal German" (Nazi) outpost in South America.

15Williams, 428, states that “About 300,000 Brazilians, many of them small farmers, arrived in eastern Paraguay in the 1970s because land was cheaper than in Brazil.” This indicates the leniency of the Paraguayan policy toward foreigners over the indigenous tribes being displaced.

16Fretz, 85.

17Fretz, 98-101.

18Ratzlaff, 24.

19The missionary contingent is a unique sociological category, but since they were basically “foreign” immigrants, except for most Roman Catholic missionaries, they are included in this rubric.

20Information on the amount of land purchased for the settlements since 1946 is not available.

21An “official Paraguayan position” is not fully accurate, for the dominant sector of Paraguay is itself highly stratified into an “elite” Spanish oligarchy and military elite, with the remainder consisting of the Guaraní amalgam which is basically lower working class – the mestizos.

22Chase-Sardi, 5 (my translation from the Spanish).

23Penny Lernoux, “Behind Closed Borders,” Harpers, February 1979, pp. 28-29.

24Ibid., 27.

25These freedoms have been included in the 1967 Constitution and revised in the Constitution of 1992. Williams, 430.

26“Some [tribes] are threatened with extinction through forced assimilation and the destruction of their traditional habitat.” Ibid., 428.

27See “Political Parties” in “Paraguay” in Encyclopedia of the Third World, Geo. Thomas, ed. (New York: Facts on File, 1992), 1535. This issue will be expanded below.

28Fretz, 17. Subsequent natural growth obviously increases the numbers.

29The settler/colonizer perceptions of Paraguayan peoples are not centrally relevant here.

30Calvin Redekop, Strangers Become Neighbors (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1980), 178.

31For an extensive resource on indigenous harassment and expulsion by Paraguay, see NEWSLETTER: Cultural Survival, Inc. (Boston). Volume 5, No. 1, 1981 focuses especially on the Chaco. For a comprehensive report, see Cultural Survival Special Report No. 2, “The Indian Peoples of Paraguay: Their Plight and Their Prospects” by David Maybury-Lewis and James Howe.

32This concession to the Mennonites has been the source of amazing advantages, but also engendered much anger and animosity on the part of Paraguayans and indígenas.

33Redekop, chapters 6 and 7. Fretz. Walter Regehr, Die lebensraeumliche Situation der Indianer im paraguayischen Chaco (Basel: Beitrage zur Geographie, 1979). Stahl, “Mission und Indianer Siedlung,” 50 Jahre, Kolonie Fernheim (Fernheim: Colonie Fernheim, 1980).

34Field research by author, 1971.

35Regehr presents indispensable information for understanding the survival and adaptation of the Indians to the modern context in the Chaco.

36Redekop, 177. “There is mixed opinion in the Indian community regarding the question of making progress in settlement; the more responsible and farsighted understand that the problem lies with the Indian’s ability to make the cultural change, while the more impatient and unreflecting Indians say it is the Mennonite stinginess.”

37One powerful example is the lack of understanding on how land is dependent on a “title” indicating position. See Regehr for a comprehensive analysis of the Indian “modernization,” especially as it pertains to the land question. It presents indispensable information for understanding the survival and adaptation of the Indians to the modern context in the Chaco, Paraguay.

38Redekop, 177.

39Wikipedia, “Vatican II” and “Conscientization.”

40The Latin American “liberation movement” is largely Catholic in origin, resulting from Vatican II and the Latin American Episcopate (CELAM II) in Medellin, Colombia, in 1968.

41Asunción: Centro de Estúdios Antropológicos, Universidad Católica, 1972.

42I am deeply grateful to Edgar Stoesz, Latin American Mennonite Central Committee director, for providing information and helping me negotiate the Chase-Sardi “affair” in its larger context.

43Chase-Sardi, 23. His description of the Mennonite-indígenas relationship is seriously flawed, because it does not put the details in context. This issue will be expanded below.

44The Barbados conference was supported by the World Council of Churches program to combat racism, directed by the University of Bern. The conference itself was sponsored by the Center for Multi-racial Studies, University of the West Indies, Bridgetown, Barbados.

45Including cessation of all missionary activities.

46January 21, 1974, 6-8.

47Ibid., 8.

48Akwesasne Notes, Winter, 1973, 26.

49Letter to Fast, Zeeuw, and Jacob A. Loewen, November 3, 1972.

50Chase-Sardi letter to Sjollema, World Council of Churches, December 5 1972, in author’s files.

51Ibid. Chase-Sardi’s accusations seem unrelated, but his extreme frustration may have caused him to undermine Mennonite credibility where possible to get the Mennonites to listen.

52H. Hack, Mennoblatt, Dec. 12, 1972, 4.

53Letter to Sjollema, November 15, 1972, in author’s files.

54New York Times, March 15, 1974.

55This could also be interpreted as an indirect criticism of Chase-Sardi.

56It is well known that Stroessner and the government held the Mennonites in high esteem, because of their outstanding economic developments and their assistance in the economic growth of Paraguay. Many Paraguayans felt the Mennonites were unfairly well treated.

57Washington Post, March 22, 1976. Written by Richard Arens, member of the board of the International League for the Rights of Man, this became a “cause célèbre” and received wide publicity.

58According to Wilmar Stahl, a respected friend, Chase-Sardi was largely mentally and spiritually destroyed, and became despondent. He died deeply disappointed that he had not fully succeeded and that the Church and other institutions had failed to help him. Interview, January, 22, 2010.

59Letter, from Charles L. Stansifer to Elmer Ediger, April 15, 1977.

60Representatives at the conference included the Ford Foundation, Inter-American Foundation, Mennonite Central Committee, New Tribes Mission, Social Science Research Council, USAID, World Bank, U.S. State Department and numerous universities and development agencies. (New Tribes Mission had received a great amount of very negative press from anthropologists and others.)

61There is renewed concern that the indígenas of the Gran Chaco are “routinely chased off their lands, pressed into debt bondage and forced to live in squalor” (United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2009). It reported on “the first-ever dialogue with governments [Paraguay and Bolivia] to discuss allegations of human rights violations” and called on both governments to take “full responsibility for ending forced labour and expropriation of ancestral lands and territories” (http://media-newswire.com/release_1117224.html). This 16-page release reports a significant action.

62During my visit to Paraguay in January 2010, the major road from Filadelfia, Chaco to Asunción, was barricaded by a large group of local indígenas. Traffic, including many commercial trucks, was detained for hours until police forcibly hauled the protesters off. Mennonite and Paraguayan truckers were very angry and expressed unprintable invectives against the indígenas.

63It can be argued that there are many other cases in history that are very similar. Fair enough, but my rejoinder is that the total population divided by the number and size of divergent group is almost a unique difference. And where it is duplicated, similar conditions might well apply.

64Interestingly, the separatist stance is rapidly being challenged and tested in the political arenas, since the governors of several Chaco departamentos are Mennonites, while a Mennonite served in the Duarte Frutos government.

65Macintyre, xii. The central plaza of Asunción is dedicated to the “Panteón de los héroes,” in which all the major national leaders are there as bigger-than-life statues, all identified as political leaders as well as military generals. This Panteón is daily guarded by a detachment of solders in full military regalia.

66Williams, 433. This is damning with faint praise!

67See the timeline on the 2008 election in Table 2.

68Williams, 428.

69Miller, 20.

70There seems to be a general consensus that missionary groups are not making a major contribution to ending “victimization” of the indígenas. The Paraguayan official stance toward foreign missionary activity is relatively tolerant, but it does not consider it to be very helpful. The Roman Catholic indígenas programs are seen more positively for obvious reasons. This is, of course, a very delicate issue for Paraguay.

71Jose Braunstein and Elmer S. Miller, in Miller, op. cit., “Ethnohistorical Introduction,” for a general overview of the present status of the Indians in the Chaco Rim” and the role the various states and organizations play in their “development,” 1-22.

72Carolina Pedro, “Foreword/Prólogo,” in Visual Encounters with Paraguay (Topeka, Kan.: Washburn University, Mulvane Art Museum, January 2008), 1.

73One of the basic premises of Anabaptist/Mennonite faith is that accepting the Christian message implies “following Christ.” That is, obedience to Jesus’ teachings and life – service.

74Wilmar Stahl. Indígenas del Chaco Central Paraguayo (Filadelfia: ASCIM, 2005), 40. There are around 44,464 indígenas today in the Chaco, 16.

75MEDA Journal Paraguay, December 2008, Vol. 30, p. 11. Other projects that MEDA is helping to develop include a promising project to process mandiocha into cooking additives, in which both indígenas and Paraguayans participate.

76Interview with Hans Derksen, Filadelfia, MEDA director, January 21, 2010.

77This perspective is expressed in Richard A. Yoder, Calvin Redekop and Vernon Janzti, Development to a Different Drummer (Intercourse. Pa.: Good Books, 2004).

| Pre-1537 | Tupi-Guaraní peoples (plus other smaller tribes) inhabit Paraguay and parts of western Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia |

| 1537 | Asunción founded by Spanish explorers; arrival of Dominican and Franciscan missionaries |

| 1547 | Jesuit missionaries begin establishing Reducciones (approx. 30) in Paraguay |

| 1776 | Spain expels all Jesuits from Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina |

| 1776 | Paraguay becomes part of Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata based in Buenos Aires |

| 1810 | Paraguay revolts against Buenos Aires |

| 1811 | Paraguay founded as independent state |

| 1814-1840 | Dictator José De Francia rules, helps establish Paraguayan identity |

| 1844-1862 | Carlos López modernizes economy, integrates Guaraní peasants into national life – a major contributor to Paraguay’s “flowering” |

| 1865-1870 | Francisco López expands military and foreign relations, economy |

| 1865-1870 | War of Triple Alliance – major catastrophe for Paraguay |

| 1871-1904 | Slow recovery; emerging Colorado and Liberal parties compete for power |

| 1904-1938 | Liberal party dominance, with little stability |

| 1928-1938 | Extended Chaco War against Bolivia ends with peace treaty |

| 1938-1954 | Decline of Liberals and ascendancy of Colorado party |

| 1954-1989 | Dictatorship of General Alfredo Stroessner – iron-fisted rule/turmoil |

| 1989 | General Andres Rodríguez overthrows Stroessner and proclaims democracy |

| 1989 | Search for stable and functioning democracy; Colorado influence wanes |

| 1993 | Juan Wasmosy wins presidency, declares it the first “democratic election” |

Courtesy of Charles L. Stansifer, Visual Encounters with Paraguay (Topeka, Kan.: Washburn University, Mulvane Art Museum, January 2008), pp. 21-22, plus other sources. Cal Redekop, March 2010.

| Name | Country Origin | Date Founded | Original Number |

| 1. Jesuit Reducciones2 | Spain | 1547 | ? |

| 2. San Bernardino | Germany | 1881 | ? |

| 3. Nueva Germania | Germany | 1887 | 160 |

| 4. Friesland* | Russia | 1937 | 748 |

| 5. Volendam* | Russia | 1947 | 1800 |

| 6. Independencia | Germany | 1920 | 186 |

| 7. Carlos Pfannl | Austria | 1931 | 200 |

| 8. Sudetia | Czechoslovakia | 1934 | 150 |

| 9. Hohenau | Brazil | 1900 | 15 |

| 10. Capitán Meza | Germany-Brazil | 1907 | 30 |

| 11. Cambyreta | Germany | 1911 | 50 |

| 12. Obligado | Germany-Brazil | 1912 | ? |

| 13. Bella Vista | Brazil | 1917 | ? |

| 14. Jesus & Trinidad | Germany | 1920 | 50 |

| 15. San Miguel | Germany | 1921 | 70 |

| 16. Alborada | Germany | 1924 | 160 |

| 17. Fram | Poland-Russia* | 1927 | 800 |

| 18. Menno* | Canada | 1926 | 1743 |

| 19. Fernheim* | Russia | 1930 | 2000 |

| 20. Primavera | England? US | 1940 | ? |

| 21. Neuland* | Russia | 1947 | 2400 |

| 22. Bergthal* | Canada | 1948 | 574 |

| 23. Sommerfeld* | Canada | 1948 | 626 |

| 24. Reinfeld* | Canada | 1966 | 146 |

| 25. Rio Verde* | Mexico | 1969 | 3,108 |

| 26. Luz y Esperanza* | USA | 1967 | 151 |

| 27. Agua Azul* | USA | 1969 | 70 |

| 28. Santa Clara* | Mexico | 1972 | 332 |

| 29. Tres Palmas* | Russia/Canada | 1973 | 198 |

| 30. Campo Alto* | Belize | ? | |

| 31. Rio Corrientes* | USA | 1975 | ? |

| 32. Florida* | USA | 1976 | 82 |

| 33. Nuevo Durango* | Mexico | 1978 | 1,822 |

| 34. La Montana* | USA | 1982 | 275 |

| 35. Manitoba* | Mexico | 1983 | 628 |

| 36. Moonies | USA | 2008? | ? |

| TOTAL3 | 18,602 | ||

1This does not include the many religious missionary groups, many having their own settlements including food-producing farms. A major mission program is New Tribes Mission.

2For a comprehensive, history, see “Paraguay Reductions” in Catholic Encyclopedia.

3This does not include continuing later immigrations, especially in settlements such as Hohenau. Neither does it include subsequent normal growth. The total today could easily be doubled or tripled.