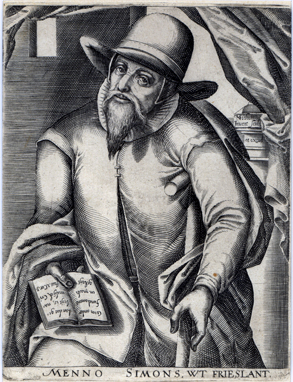

by Christoffel van Sichem

James Stayer is emeritus professor of history at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario and has been a teacher and writer of history from 1959 to the present. He grew up in Lancaster County, Pa., received his undergraduate education at Juniata College, Huntingdon, Pa., earned his Ph.D. from Cornell University and later taught at Bridgewater (Va.) College. He emigrated to Canada in 1968 and became a Canadian citizen in 1977. He has authored two books on Anabaptist/Mennonite history, Anabaptists and the Sword (1972) and The German Peasants’ War and Anabaptist Community of Goods (1991) and, more recently, co-edited two collections on the radical Reformation, Radicalism and Dissent in the Sixteenth Century (2002; with Hans-Jürgen Goertz) and A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism (2007; with John D. Roth).

The great majority of the world’s Anabaptists are called either “Mennonites” or “Amish,” the result of a schism that occurred ca. 1700. Members of a different Anabaptist tradition are called “Hutterites.” These names evoke the memories of the early leaders Menno Simons, Jakob Ammann and Jakob Hutter. The affiliated movement in the Netherlands is called “Doopsgezinden,” for which the sensible and obvious English translation would be “Baptists,” except that the smaller Anabaptist and the larger Baptist tradition have preferred to underscore their distinctness – the Baptist tradition that originated in England and then spread throughout the world regards itself as springing from a combination of Anabaptist and Calvinist sources.

|

The Anabaptism of the Netherlands and the North Sea and Baltic coasts began with the career of Melchior Hoffman. That is my opinion; it is the unanimous view of the scholars connected with the Doopsgezinde church of the Netherlands, as well as of the postconfessional scholars who write their history. Among contemporaries only Abraham Friesen seems to dissent from this view – he contends that Menno got his views on believers’ baptism purely from a study of Erasmus’ treatment of the Great Commission (Matthew 28: 19, 20) in his Paraphrases on the New Testament. Friesen’s position is not without substance, Cornelis Augustijn has shown that Menno read Erasmus in Latin and had a serious theological debt to him. But the notion that Menno’s thought and the early Mennonite tradition comes primarily from Erasmus can be a device to deny the obvious debt to Hoffman. In the 1520s Hoffman, a furrier by trade, was a lay missionary for the Reformation in the Baltic region. As early as 1526, he was foretelling the end of the world for 1533. The disorder, riots and iconoclasm connected with Hoffman’s lay apostolate got him into trouble with university-educated Lutheran clergymen, as the Lutheran Reformation became increasingly established in the Baltic lands.

|

The next stress of Hoffman’s theology was a two-way covenant between God and the individual human being. People were intrinsically sinful and only through the grace of the sinless Christ could they be redeemed, but this grace was extended to everyone, and the redeemed person was fully able to respond to God’s grace by a regenerate life. Moreover, anyone who abandoned the covenant knowingly and wantonly (with something more than a mere stumble or slip) was irretrievably lost – here the characteristic Melchiorite doctrine of the unforgivable sin. The seal of the covenant knowingly and responsibly entered into was the baptism of the mature believer: it was a symbol of the covenant, the ring Christ gave his human bride. But Hoffman did not stress baptism as much as other Anabaptist leaders; characteristically, we know nothing about his own baptism. Always important for Hoffman was his self-understanding, following Revelation 11, as one of the two witnesses of the last days; tradition associated these two witnesses with Elijah and Enoch, the two people caught up into heaven alive. Hoffman’s following of Strasbourg prophets convinced him that he was the apocalyptic Elijah. Just exactly what would happen with the last days was murky. It had overtones of righteous violence. The prophet’s immediate following would eschew all violence, but they would support godly rulers like the government of Strasbourg, who would withstand the attack of the Imperial dragon in the final tribulations. Hoffman never separated the true church and the secular government with the decisiveness of a Michael Sattler, a Pilgram Marpeck or even a Balthasar Hubmaier. A Christian ruler was not a contradiction in terms for him, but rather a source of apocalyptic hope. Much of what we know about Melchior Hoffman helps us to better understand the Münster episode, as well as the theology of Menno Simons, especially in the early stages of his calling as an Anabaptist leader.

Melchior Hoffman began baptizing adult believers in the city of Emden in 1530, while on a trip from Strasbourg to East Frisia. East Frisia was an independent principality bordering on the Habsburg Netherlands, which at that time had its capital in Brussels. East Frisia was open then to various kinds of Protestantism because of the friendly attitude of its ruler and aristocracy. The Netherlands government was trying to enforce Catholic orthodoxy but not doing so very effectively because of the stubborn local independence of its provinces and cities. The majority of religious people in the Netherlands, including many priests, were in those years sympathetic to some kind of reform. They were aware of Luther and Erasmus, without making very clear distinctions between their teachings – in general they were open to a symbolic interpretation of the Lord’s Supper of the sort taught by Ulrich Zwingli, Andreas Karlstadt, and, of course, Melchior Hoffman. In these conditions Hoffman’s teaching of adult baptism had easy entry from East Frisia to the Netherlands. It seems, however, that only the minority of reform supporters who were caught up in Hoffman’s belief in the imminent end of the world exposed themselves to the scrutiny of government officials by the overt act of adult baptism. When a number of Hoffman’s prominent followers were executed at the Hague in 1531, he was sufficiently shocked that he declared a two-year suspension of adult baptisms – that is, until 1533 when he expected the end of the world. So Hoffman’s apocalyptic message spread in a more underground manner among groups of the convinced in the Netherlands and surrounding territories. Meanwhile, in the appointed year 1533 and in Strasbourg, the city he expected to be the New Jerusalem, Hoffman was imprisoned by a now less tolerant city government that was turning in the direction of Protestant orthodoxy. He remained in jail for ten years, apparently until he died.

|

This same year, 1533, was the year of important changes toward a radical reformation in the Westphalian city of Münster. Münster was a semi-independent city ruled by a council and an assembly of guild masters, under the overlordship of a prince-bishop. Its Reformation was headed by Bernhard Rothmann, a local cleric with strong support in the guilds and the less privileged citizenry. Impatient of orthodox Lutheranism, which was becoming dominant in all the pro-Reformation territories in Germany at the time, Rothmann and his fellow pastors opted for a symbolic view of the Lord’s Supper and for a theoretical support of adult baptism (without actually putting it into practice). Münster attracted the attention in 1533 of Melchiorites from the Netherlands, like the young innkeeper Jan Beukels of Leiden, who visited in the summer; and its pastors’ writings on the sacraments were presented to a gathering of Melchiorites in Amsterdam at the end of the year. Hoffman’s two years were up; the prophet was languishing in prison in Strasbourg; hence his authority was obviously on the wane. In these circumstances an unstable baker from Haarlem, Jan Matthijs, declared that he was “Enoch,” the second apocalyptic witness of Revelation 11, and that adult baptism should resume immediately.

|

|

What was the role of Menno Simons, priest in Pingjum and Witmarsum in Frisia from 1524 to 1536 and most likely the brother of Peter Simons, one of the Twelve Elders whom Jan of Leiden had commissioned to rule Münster from April to September 1534? An autobiographical fragment written late in life reveals some parts of his story, and perhaps conceals other parts. Like many Catholic priests in the Netherlands Menno was an evangelical reformer, aware of Erasmus and Luther. He had come to doubt the doctrine of transubstantiation, the official Catholic explanation of the mass, and the execution of one of Melchior Hoffman’s followers in Frisia had led him to turn away from infant baptism. In 1536 he abandoned his parish and went into hiding, soon to be commissioned as an elder of the scattered Anabaptists shattered by the disaster of Münster. Was he, then, someone entirely untouched by earlier Anabaptist mistakes – a late-born savior of the movement who came in from the outside to sanctify the succession of adult baptisms that Jan Matthijs began in the last months of 1533, perhaps on the basis of his study of the Great Commission as exegeted in Erasmus’s Paraphrases on the New Testament? This seems improbable if only because, throughout his life, he taught the characteristic doctrines of Melchior Hoffman.

In the early twentieth century the maverick Dutch Doopgezind pastor Karel Vos suggested that Menno was likely baptized and became a Covenanter in 1534. This view has been endorsed in the recent book by Helmut Isaak, Menno Simons and the New Jerusalem (2006). Based on suggestions by twentieth-century scholars Vos, W. J. Kühler, and H. W. Meihuizen, together with his own close textual study of Menno’s writings in various editions, Isaak has proposed an order of composition of Menno’s works that varies widely from the dates of publication of preserved editions, carefully researched by Irvin B. Horst. Not all of Menno’s works were published when they were written. The case of “On the Blasphemy of Jan of Leiden,” attributed to Menno, but not published until 1627 apparently for the first time, merits special attention. The work’s authenticity has, of course, been debated. Isaak demonstrates correspondence between the text of the “Blasphemy” and other works of Menno – the Meditation on the Twenty-Fifth Psalm, The New Birth, and both the earlier and later editions of the Foundation Book. These textual linkages could perhaps be used to make the case that the “Blasphemy” was a particularly ingenious forgery, but for Isaak they show its genuineness. Written during the Münster kingdom, it expresses Menno’s outrage at Jan’s usurpation of the prerogatives of Christ; that it was never published during Menno’s lifetime was due to his shame and embarrassment about its reflection of his close ties to the Münster Anabaptists. Isaak argues that Menno was well-versed in the writings not only of Melchior Hoffman but of Bernhard Rothmann as well. That Menno never, throughout his career, abandoned the Melchiorite notion of the godly ruler means to Isaak that, at the height of his influence in the 1540s, Menno had serious hopes of finding a ruler who would direct his subjects to the true religion, as did the Old Testament exemplars Joshua, Hezekiah, and Josiah. Menno was seeking his own Constantine, so to speak. According to this way of looking at Menno’s trajectory, the 1550s were the decade of disillusionment for him – supported by the Habsburg government in Brussels the inquisitors tracked down Mennonites and gave them the stark choice of recantation or death; there were an estimated one thousand Mennonite martyrs. At the same time a competing variety of Protestant, the Calvinists, moved into the Netherlands from France and Emden. They attracted aristocratic as well as bourgeois support, and in the 1560s the Calvinists were able to launch the revolt that created the Dutch Republic. The Netherlands were too hot for Menno; he left followers behind there, “suffering under the cross,” and he moved with relative freedom among followers in the Rhineland and along the North Sea and Baltic coasts. Now he accepted the fate of leader of a separated people, the “still in the land,” and issues of discipline, excommunication and marital shunning dominated his last years with their stress on the creation of a “congregation without spot or wrinkle” (Ephesians 5:27). Still, this picture is possibly over-schematized. Isaak has argued convincingly that Menno studied Rothmann, and Rothmann’s writings contain recurrent references to Ephesians 5. What Isaak has done is to raise the issues about Menno and Münster, and the trajectory of Menno’s theological and ecclesiological development. He has not given certain answers to the questions he asks, but he has introduced provocative questions into our interpretation of Menno.

In the first edition of his Foundation Book (1539/40), the classic statement that began Menno’s emergence as the presiding elder of Anabaptism in north Germany and the Netherlands, Menno looked back with compassion on the rank and file of militant Anabaptists who had fought in Münster, and who had fought for Münster at Oldeklooster in Frisia in March 1535 and in the Amsterdam uprising in May 1535: “I do not doubt but that our dear brethren who have formerly transgressed a little against the Lord, when they intended to defend their faith with arms, have a merciful God.” The sentence was deleted from the revised edition of the Foundation Book published in the 1550s. This compassion, of course, did not extend to the leaders who led these Anabaptists into violence, or to the “covenanters of the sword” who continued small-scale violence after the fall of Anabaptist Münster under Jan van Batenburg and his successors. In Menno’s eyes they were false prophets.

|

|

This lecture has emphasized, perhaps overemphasized, the odd fit between Menno Simons and the churches who now call themselves “Mennonites.” The beginnings of Anabaptism in north Germany and the Netherlands were very different from Anabaptist beginnings in Switzerland and south Germany, yet, like the Russian and Pennsylvania German Mennonite immigrant streams in America, the two traditions gradually appropriated each other’s religious heritage.

So what does this add up to? I am reminded of Heinold Fast’s comment to me in 1975 at the 450th anniversary celebration for the Zurich baptisms at Rüschlikon, Switzerland. “Jim Stayer has told us that there are great differences among the Anabaptists. Perhaps so; but we here are looking for something more than that.”

To the extent that you find these lectures convincing (and, I myself do not find them absolutely convincing; not all of the pieces of the historical puzzle fit together flawlessly); we may conclude:

There was a big divergence between 1525, the first year of Anabaptism, when political and church authority was shaken by peasant uprisings in Switzerland and south Germany, and 1526 and onward after authority was restored.

The more pragmatic Anabaptism of Conrad Grebel and Balthasar Hubmaier was better suited to the first period and the nonresistant separatism of Felix Mantz and Michael Sattler was better suited to the raging persecution of the second period.

The Anabaptism of Pilgram Marpeck diverged from that of both the Hutterites and the Swiss Brethren in the 1540s because it was more urban, less confrontational, and more theologically sophisticated.

The Anabaptism of Menno Simons in north Germany and the Netherlands diverged from Swiss-south German Anabaptism because it was marked by Melchior Hoffman’s special Christology and more positive view of the state. Although Menno denounced the Anabaptist regime in Münster, he agreed with the Münster Anabaptists on Christology and the positive view of the state.

Despite all these differences there was a sense of family connection among Anabaptist/Mennonites. The Dutch Mennonites came to the assistance of the Swiss and south German Anabaptists, because they were prosperous and secure and could afford to do so. Marpeck’s work had some influence on Swiss and south German Anabaptists in the late sixteenth century; and it was recovered for the Anabaptist/Mennonite community in the twentieth century.

The impact of the Mennonite peace theology for the twenty-first century can be differently construed. Is a recovery of sixteenth-century Anabaptist nonresistance the Mennonite gift for the church and the world? Or should nonresistance transform itself into nonviolent resistance to war and social injustice? A mutually respectful conversation continues.

Augustijn, Cornelis, “Erasmus and Menno.” Mennonite Quarterly Review 60 (1986): 496-508.

Bakker, Willem de, Michael D. Driedger and James M. Stayer. Bernhard Rothmann and the Reformation in Münster, 1530-1535. Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press 2009.

Deppermann, Klaus. Melchior Hoffman. Social Unrest and Apocalyptic Visions in the Age of Reformation. Edinburgh: T & T Clark 1987.

Friesen, Abraham. Erasmus, the Anabaptists and the Great Commission. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eeerdmans 1998.

Isaak, Helmut. Menno Simons and the New Jerusalem. Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press 2006.

Klötzer, Ralf. “The Melchiorites and Münster” A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, John D. Roth and James M. Stayer, eds. Leiden: E. J. Brill 2007, 217-36.

Visser, Piet. “Mennonites and Doopsgezinden in the Netherlands, 1535-1700” Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 299-345.

Wenger, John C. ed. The Complete Writings of Menno Simons. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press 1984.

Zijlstra, Samme. Om de ware geemente en de oude gronden. Geschiedenis van de dopersen in de Nederlanden, 1531-1675. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren & Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy 2000.