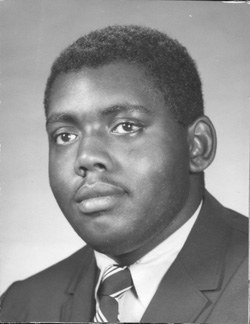

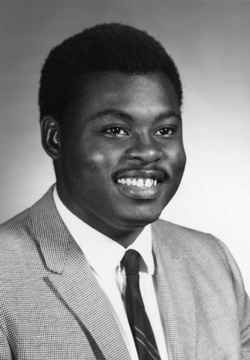

Michael Burnett (1968 Bethel yearbook)

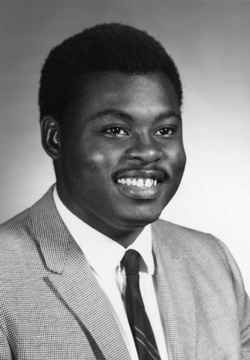

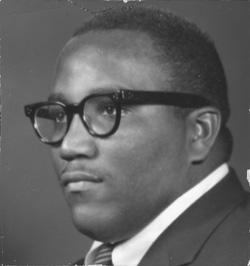

Willie Price (1969 Bethel yearbook)

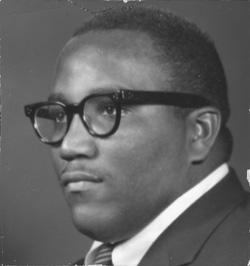

George Rogers (1968 Bethel yearbook)

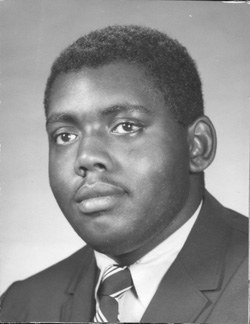

J. Earl White (1969 Bethel yearbook)

Spring 2008

vol. 63 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Spring 2008

vol. 63 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Ardie S. Goering is a writer whose work includes a monthly column entitled "Due Consideration" in the Mennonite Weekly Review, an inter-Mennonite newspaper. A graduate of Bethel College, she is particularly interested in Mennonite culture and identity. Goering lives most of the year in Albuquerque, New Mexico and maintains a second home on a farm near Goessel, Kansas. She and her husband, Wynn, are continuing a Christmas tree business at the farm started by her parents over 30 years ago.

|

|

|

|

Michael Burnett (1968 Bethel yearbook) |

Willie Price (1969 Bethel yearbook) |

George Rogers (1968 Bethel yearbook) |

J. Earl White (1969 Bethel yearbook) |

When Bill Price came to the Bethel College campus in the fall of 1967, he had a bold curiosity and a legacy of tenacity and hard work. From Bassfield, a tiny town in the southern quarter of Mississippi, Price grew up on a sharecropping farm, a system where the owner supplied the tractor, gasoline, and half of the cost of fertilizer. "We furnished the labor," explains Price, "and when we took our cotton to market, we settled and received our share of the money."(1)

In time, Price's family saved enough to buy their own land, not easy in an economic system where African-Americans could not work in factories and the only jobs for black women were as maids for white women. "My mother was a good manager," says Price in explaining how they climbed up an uneven ladder.

Between crops, Price's stepfather also worked in a lumber company owned by the man upon whose property they lived. They grew a garden and canned the produce, butchered their own hogs and took corn to a grist mill. Self-sufficiency was prized, but they were still difficult years.

"My mother finished 8th grade and my stepfather had some elementary education, but I'm not sure how much," explains Price. The only secondary education available to Price's parents was private, made possible by people wanting blacks to have that opportunity, but it was not easily accessible. "Public education was not a right for African-Americans," says Price matter-of-factly about the formative years of a generation before him.

The local public schools were not integrated until 1970; before that, Price finished high school and two years at a junior college, both segregated for black students only. He was offered a scholarship at Jackson State College, also segregated. But he knew of Bethel College from Mennonites doing service work in the area, and Bill Price was curious.

"Segregated schools taught pride and confidence. They got you out of 'inferiority thinking' and taught you that you could do anything you wanted to do," remembers Price. "But I wanted to know if there was a difference in education from what I was getting. I wanted to go to an integrated college and I wanted to leave the state of Mississippi."

* * *

There are no accurate statistics about how many students of color have attended Bethel College in North Newton, Kansas, since its founding in 1887. Selection of race/ethnicity by students themselves began only in the 1980s. In recent years, the college's African-American Alumni Association has attempted to personally identify black students among living alumni, coming up with an approximate and probable underestimate of 3 percent of the total student population.

Anecdotal knowledge points to African-American students at Bethel as early as the 1920s and 1930s, with a scattering of black students in the years before Bill Price came to central Kansas in the late 1960s. "There were nine of us, I remember clearly," says Price about black students on campus. Three of them were Earl White, George Rogers, and Mike Burnett.

White was a local guy; his grandparents had homesteaded east of Newton in 1872. His aunt was in the first graduating class of Walton High School, a few miles from Newton, and his mother was a graduate of Sterling College, also in central Kansas. Earl White had graduated from Garden City Junior College in 1961 and served in the Air Force for three years after that. He worked for the railroad for 1 ½ years and then came to Bethel on the GI Bill. Bethel College was a likely choice for White, since other family members had already been to Bethel, including his wife, a Bethel graduate herself.

George Rogers first arrived on the Bethel College campus in the spring of 1967 for the Buffalo Barbecue, an annual and popular athletic tradition. Rogers was looking at other larger colleges at which to play football, but he found "big-town football too controlling," he explains. "I was not going to let people control me." Plus, Rogers liked Otto Unruh, Bethel's football coach, "a gruff old guy." Rogers came from Chicago, graduating from a special track pre-engineering high school, but initially had doubted whether he had the "ability to go to college, both financially and intellectually. Going to college was not part of my world."

It was Rogers' buddy, Mike Burnett, who planted Bethel in his mind. Burnett, also from Chicago, became acquainted with Bethel in Kansas because his family knew someone who had gone there, another African-American student named Barbara Wright, whose mother was from Newton. Burnett was a good student; his mom had gone to college and encouraged him to go also. After Burnett had been to Bethel one semester, he pushed Rogers to get out of Chicago and get a degree. A college education would be something more than chasing girls and trying to make money.

"It would be different than everything we know," Mike appealed to George.

* * *

The Monday morning following George Roger's Friday afternoon high school graduation, his dad roused him out of bed to go look for a job. "I needed either to be in school or working," Rogers explains when asked what his parents were like.

He went to work for a U.S. Steel mill, where the open furnaces were so hot that men brought raw meat in the morning and cooked it for lunch that day. School didn't look so bad after that, so Rogers first went to local Wilson City College before landing at Bethel. After the hustle and bustle of urban and industrial life, Rogers was ready for a "quiet experience." His first impression of Bethel College? "Lots of friendly people," he said.

Nationwide, the late 1960s were a time of cultural changes and political challenges, including the civil rights movement. At Bethel, Rogers found "people wanting to do the right thing." His senior oral examinations focused on both Job from the Old Testament and Malcom X from contemporary life. Rogers remembers black and white students dancing together when the first dance that was not folk or square-dancing, was held on campus in 1967. "A lot of people considered themselves liberal," Rogers says, "and there was never a lack of people who wanted interaction. Bethel wanted to be integrated."

|

|

Warkentin Court Governing Council 1967-68, |

Bethel College Recreation Council 1967-68, Burnett - left (1968 Bethel yearbook) |

Yet Rogers found himself in a particularly close relationship with Mike Burnett, whom he knew from high school in Chicago, and two other African-American men, Earl White and Bill Price.

They all played football and did not have much money.

"The four of us got together because we were black," Rogers remembers.

Even though the four men came from different backgrounds, "we were black, " Bill Price says. "And that kept us together." It's natural to "want to connect with someone who looks like me," he continues.

"We were black," says Earl White in remembering how the four first became friends. "Nowadays, there is a minority student organization" that offers support for African-American students. But in the late 1960s, "I was the minority resources center" for this particular group of guys, White says with a wry smile.

With his wife, Ruth, Earl White provided a "second home" that was off campus; White's mother also invited the boys to her Newton home. "Earl's family was good to us," says Rogers. The four young men played cards, ate holiday meals, and spent time together despite the cultural divide of three geographic hometowns, urban Chicago, the deep south, and midwestern Kansas. "We had our differences, but they were interesting, and not a barrier," recalls White. "Being black drew us together."

The sense of belonging in White's extended family was particularly important for three of the young men who were a long way from home. "I remember sitting on the men's dorm fire escape steps one day, feeling particularly sad and lonely," says Price. "My mother had told me not to come here, and I wondered if she was right." On some days, there were difficult encounters with some white students, because they "were not used to blacks," Price says carefully.

While sitting on those steps in a blue mood that day, "another student came by and asked me how I was feeling. He was really nice to me," Price continues. "Some of the students were supportive."

A different kind of help was offered by English professor Honora Becker, who rolled out a welcome mat to Willie Price, a young man bright enough to later earn a Ph.D. in social work, but who came to Bethel needing remedial work. "She tutored me around her coffee table," he says.

Were all the Bethel faculty and administrators this supportive? "Some were," Price responds, and some of the faculty "did not have my best interests at heart."

In the December 13, 1968, issue of the Bethel student newspaper, the Collegian, an article entitled "Role of the Black Athlete, Mistrust and Acceptance" by David Janzen, quoted Mike Burnett, who had come to Bethel three years earlier as one of only two black players (along with White) on the football team. By the fall of 1968, nine African-Americans played football and Burnett described how he saw things change in that time.

"When I first came here, I was unique. I felt pretty well accepted by my teammates, coaching staff, and teachers. But now the black athlete is looking for more overall recognition, to be accepted as a whole person."

The article goes on to say that for Burnett, acceptance had been hard to find. He believed that teachers had treated him "average." Furthermore, the coaching staff and white teammates "can not really be blamed, since most of them don't know what it's like to play with a Negro. The hardest part is telling what is premeditated and what just happens. I like to think about it a long time before I label anyone a racist."

* * *

A year and a half ago, and before he could be interviewed for this article, Michael Burnett died unexpectedly of complications from a chronic disease at a relatively young age of 59. His death was a sad shock to the other three men.

Bill Price, who struggled with his own health problems including a kidney transplant a year and a half ago, says he believed he would be the first to die among the four men. "Michael was the glue that held the group together," says Price.

"Mike was more than cordial," says George Rogers. "He was kind and thoughtful, he tried to make people feel at ease. And he made certain everyone stayed in touch after Bethel," Rogers continues.

After all four graduated from Bethel in 1969, Mike Burnett moved back to Chicago, where he made a point to check on Rogers' folks. After Rogers' mother died of a stroke, Mike met George at the airport and said, "When is the funeral? I'll be there."

A friendship between the four men that had become closer and closer during their time together at Bethel solidified into something more, a "kinship and a brotherhood," after they headed into different directions after college. Although Rogers and White stayed in Newton, Burnett and Price moved to other parts of the country. "But we all made the effort to stay in touch and visit each other," says White. "We attended the marriages of children, things like that."

"When we get together, it feels like it has been a long way to come together," explains White, "but it always feels like home."

"Friends for life" is a kind of mantra for small colleges like Bethel, both a description of how many students develop lifelong relationships while on campus, and an invocation of a special characteristic that Bethel believes it can deliberately nurture and offer as part of its college experience.

Many white Mennonite students strongly identify with Bethel as "their school" even before they attend their first class. They often have family members who are graduates, or attend a church that closely supports the college. Lifelong friendships that evolve from these connections are based on similarities that African-American students or non-Mennonites often do not have.

George Rogers, who would go on to work at Bethel as coach, faculty member, and administrator for 29 years, recalls a white student from the Midwest saying he definitely could not become "friends for life" with a certain group of students, both black and white, from Florida.

Earl White is blunt when asked why the four became so close. "I sometimes feel Bethel takes credit for getting us together," he says. "And whereas Bethel put us together, and the Mennonite environment forced us together, our relationship grew out of something we had with each other."

Bill Price recalls "white people being very important to me at Bethel, people who had me in their homes. I had very warm, good times with people who were white," he says. But he adds reflectively, "I don't keep in touch with them" since leaving Bethel.

When asked if he considers Bethel "his school," Price says no, because he doesn't get back to participate in things. "I went back to the Bethel campus at one point, and walked around," he says. "I felt like a stranger."

Rogers believes that Mike Burnett would have said that Bethel was a good place to be and that he learned things there. But he had mixed feelings about the faculty and believed African-American students were not always treated fairly. Burnett felt it leaves "a bad taste in your mouth," he explains.

Rogers, certainly the longest-employed African-American faculty or administrator in Bethel's history, believes that many black students may "enjoy their time at Bethel, appreciate it, but not identify with it. Black students often don't feel Bethel is their place."

* * *

By any measure, White, Price, Burnett, and Rogers are among Bethel's most successful alumni.

Earl White, who grew up in a segregated Newton community, has stayed loyal to his hometown. Other black friends from his childhood moved away for better opportunities, but White stuck around. Why is Newton important to him? "Because it's my hometown," he answers.

His career has been eclectic. He worked a long twenty-year stint as a drug and alcohol counselor at Prairie View Mental Health Center in Newton, plus managed a local antique store for another five years. In 1985, he made a bold leap by starting his own heavy highway construction company in Newton. It's the only African-American owned business in the area, and in 2003, Earl White was named the Minority Small Businessman of the Year in a 77-county section of central and western Kansas.

Whitewing Construction has grown into a business that employs about 25 people in the high part of the season and generates revenue anywhere from $3 million to $5 million annually. Working across three-fourths of the state of Kansas, Whitewing does highway and street concrete flatwork, the construction of sidewalks, curbs and gutters, and the installation of guardrails and fences.

White has remained loyal to the insurance company, bonding agent, and banker who started with him over twenty years ago. "Other people say to me, why not shop around," he explains. "But those people took a chance with me."

"I wanted to be able to relate to people as I wanted to," says White in explaining why he started his own business with all the inherent risks. It is a calm and matter-of-fact attitude that White reflects also in talking about relating to a dominant white culture all of his life. "People treat me differently as a black person. Always have. Always will," he says. "There is always someone wanting to put you in your place."

How does that feel? "I've accepted it," he answers. But how does it feel? "It doesn't feel good," he responds.

For the last eleven years, Whitewing has sponsored a college scholarship for an African-American or Hispanic student who grew up in Newton and has the economic need for it. "My hope is that a black child can look to Whitewing and say, 'I can do it too,'" he explains. "My intention is that this student will come back and participate in this community."

After graduating from Bethel in 1969, Michael "Mike"Burnett went to work for Traveler's Insurance, starting as an auditor and eventually working up to regional manager. He retired in 2005. Having lived in Chicago and Hartford, Connecticut, he was residing in Midlothian, Virginia, when he died in late 2006.

Willie "Dr. Bill" Price earned a master's degree in social work from Washington University in St. Louis in 1971. In the late 1990s, he completed both a specialist degree in education administration and a Ph.D. in social work from the University of Minnesota. Price worked as a clinical social worker in family and mental health services as well as a professor of social work administration. He currently lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and is a retired principal in that school system.

He now teaches school business administration in an on-line university and does a variety of volunteer work, including teaching a church school group of boys in 6th-8th grades. He is also starting work on a memoir of his mother, who still lives in Bassfield, Mississippi.

George "Jolly" Rogers worked at Bethel College from 1969 to 1998, including work as a defensive coordinator for the football team, head coach for men and women's track, and athletic director. He was dean of students from 1992-1998. He was a strong support for all the students, black, brown, and white, who brought their own unique set of experiences to the campus.

He earned a master's degree from Wichita State University and played critical roles for athletics at Bethel; he was named the NAIA District 10 Administrator of the Year in 1990. Rogers is currently in charge of operations for Whitewing Construction, after White stepped into a less active role several years ago.

On one Thursday night of each month, Rogers can be found playing bingo with other black professionals of Kappa Alpha Psi, to raise money for Wichita area African-American students with merit.

"The results of our success are apparent," says Rogers in describing one characteristic that the four men share. "We've all had this drive to succeed. Other people in our lives would not necessarily have seen it. We were not academic types, for example."

"We don't talk about it," he says about his lifelong friends. "But we recognize it in each other."

1. Author's interview with Bill Price (October 9, 2007). All direct attributions in this article are from personal interviews with Price, Earl White (October 27, 2006) and George Rogers (October 25, 2006; May 2, 2007).