Paul Friesen in his studio at Schowalter Villa (photos by John D. Thiesen)

Spring 2007

vol. 62 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Spring 2007

vol. 62 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Paul Friesen is an influential ceramist, professor emeritus, and pastor whose lives in art, in the church and in educational institutions have cross-fertilized over the years. Editors at Mennonite Life wanted to ask questions about the intriguing relationship of art and theology in this significant life story and the life stories of congregations and student bodies. This interview is by no means a complete memoir; the editors hope that the intriguing larger themes emerge from the texture of the narratives. We take our title from a memory of an important worship service developed by Paul Friesen on the subject of racial conflict during the era of the Vietnam War, and invite readers to reflect on the meanings offered in the worship service.

(Note: In addition to the photos within the interview text, an extensive photo essay of Paul Friesen's works in wood and clay can be found at the end of the interview.)

Our interview began in Paul Friesen's studio in the basement of the Wellness Center at Schowalter Villa in Hesston, Kansas. He began with a few comments on current projects, including a sculpture called "Refugees."

Paul Friesen in his studio at Schowalter Villa (photos by John D. Thiesen)

PF: Following my seminary training at Goshen College Biblical Seminary, I served as an assistant to Roy Roth, pastor of the Plesant Hill Mennonite Church between Morton and Peoria, Illinois. An additional assignment was to work toward planting a church in Highway Village, currently a part of East Peoria. Since I was not married, the Roth family invited me to make my home with them. In November of that same year I was married to Wilma Wenger of Wellman, Iowa. But during those six months, I felt very much a part of the Roth family. During that time, Roy and Carolyn, I'm sure, discovered many of my interests which later prompted Roy, when President of Hesston College, to consider introducing art into the curriculum at Hesston.

In 1951 Roy accepted the call to be President of Hesston College. The same year I accepted a call to pastor the West Sterling Mennonite Church in Sterling, Illinois. Two years later, I had a call from Roy asking if I would come to Hesston College to establish an art program. The Kansas State Department of Education, the accrediting agency for the two year teacher training program at Hesston, informed the college that unless they included elementary art in the curriculum for elementary teachers, they would lose their accreditation for the two year program. Roy had a problem: first of all, the Mennonite Board of Education accepted only instructors who were committed members of the Mennonite Church; secondly, potential candidates for the position were hard to find in the Mennonite Church at the time. Mennonite professional artists feeling unwelcome left the Mennonite fold as refugees for a more accepting community. These circumstances possibly led Roy to see if I would accept the challenge.

Teaching was never one of my career options. I informed Roy that I had no interest in teaching and furthermore, I had no credentials that would allow me to be certified by the State Department of Education. Roy had his back against the wall and was not about to give up on me. Checking with Silas Hertzler, chairman of the Department of Education at Goshen, he informed me that within a year at Goshen I could complete the requirements for accreditation in Kansas. Returning to Goshen was not an option. Discussion continued for two years when in desperation, Roy pled with me to consider the challenge. He got me at a time when I was ready to make a move and in a moment of weakness, I gave in and accepted.

Shortly after accepting the invitation from Hesston, I had two letters, one from a church in Ohio and the other from a church in California that were looking for someone to fill the pastoral vacancy in the congregation. After getting to Hesston and learning something of the difficult time the college was experiencing, I wished the letters from the churches had come a little earlier. Now it was too late and it was now a matter of committing myself to getting back into college for preparing myself for a career I had never intended to get into.

"Refugees," 1960, 2006, black walnut,

at Hesston College Library (photo by John D. Thiesen)

The sculpture "Refugees" was part of my graduate thesis exhibit at Fort Hays State College. Due to a lack of time for finishing it the way I would like to have, it was left in somewhat of a rough finished state and remained so for forty-nine years. Then, at the time of Roy's death, I decided the piece needed to be finished and be dedicated in honor of Roy and Carolyn Roth who deserve much credit for opening the door of the (Old) Mennonite Church to young people interested in the visual arts.

JT: Your story leads into a lot of things that I'm interested in, which are more historical kinds of questions or biographical kinds of questions. You alluded to the fact that people already knew you had an interest in art. I'm curious how that originated. Where were your art interests stimulated? Who were your childhood influences, mentors, and teachers?

PF: My parents were missionaries in India. My father (Peter A. Friesen of Mountain Lake, Minnesota) and his first wife, Helena (Hiebert) Friesen went to India in 1909. They served under the Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities but were members of the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren Church of Mountain Lake who supported them while on the mission field. In 1920 Helena died in Naini Tal, a hill station in the Himalaya mountains where the Friesens had their children in school. Two years following Helena's death my father married Florence Cooprider of Hesston, Kansas. Florence, influenced by Mary Burckhart, a returned India missionary widow, felt called to become a medical doctor to serve on the India mission field. Indian women refused to be treated by male doctors or ther husbands refused to allow male physicians to care for their wives. Florence was the first woman in the (Old) Mennonite Church in the States to attend medical school.(1) While on the field, she had become a good friend of the Friesen family who did much to encourage her during her first difficult term of service. She was the attending physician when Edward, Peter and Helena's youngest son, was born. Upon Helena's death, Dr. Cooprider offered to assist Peter by taking care of two of the younger children so he could spend more time in his evangelistic work in the villages. This compassionate act must have won the heart not only of Peter but also his children, for wanting Dr. Florence Cooprider as wife and step-mother.

To this second marriage, my younger sister Grace (Friesen) Slatter and I were born. By this time a number of the missionary children from the mission were attending Woodstock School at Landour in the Himalayan mountains north of Delhi. It was at Woodstock that my interest in art was stimulated. It was a very classical orientation to the visual arts, primarily drawing and water color. My interest in sculpturing was inspired by Indian craftsmen who carved walking canes, furniture pieces, screen dividers, etc. A particular pine tree in the mountains had thick soft bark which one sculptured with a pen knife. The latter activity became a favorite pastime for me. While on winter vacation on the plains with my parents, Dad had a garage which I used as a wood working shop. It was a village farmer who really gave me the urge to sculpture. Termites had eaten the walnut gun stock on his dry powder rifle, making it useless. Wild animals were making havoc out of his crops and he wanted the gun fixed; could I make a new one? I accepted the challenge, making one out of teak which termites don't attack. My tools consisted of ordinary carpenter chisels, wood rasps, a hand-cranked drill. The gun was returned and payment for the work was to be the hind quarter of the first deer or wild pig. He brought me the neck of a deer. It was all that the village Hindu priest left for him to bring after dividing the rest among the villagers. Our cook decided it was good only for our two pet terrier dogs.

I did not finish my secondary schooling at Woodstock. My parents were due to return to the States for retirement in 1941. World War II was being fought and passage to the States was becoming difficult to arrange. The United States was not yet involved in the war but my parents felt leaving Grace and me in India to finish our final year of high school unwise. We finished our last year of high school at Hesston Academy in Hesston.

Coming to the States and attending school at Hesston was a difficult adjustment for me. Woodstock was an ecumenical community, with just about every Christian denomination represented, as well as other religious groups such as Hindu, Islamic, and Zoroastrian. For me, Mennonites were those from the General Conference Mennonites and the so-termed "Old" Mennonites. We hobnobbed together. I found it disappointing to see little cooperation, interaction between the General Conference Mennonites and the (Old) Mennonites. Yet I had Woodstock schoolmates at Bethel, names like Templin, Isaac, Wiens with whom I longed to associate with. President Milo Kaufman sensed my disappointments and my feelings about leaving the Mennonite Church. He encouraged me to be patient, assuring me that the church was making changes and perhaps I could in some way be a participant for constructive changes. Maybe it is in the area of the visual arts that I leave a small legacy?

JT: So then from Hesston you went to Goshen?

PF: From Hesston I went to Goshen. Milo encouraged me to go into the pastoral ministry and to attend seminary at Goshen. The military draft during WW II was enlisting all able bodied young men and Mennonite young men were going into CPS as conscientious objectors. Many were experiencing difficulty in getting a conscientious objection status. My draft board was in Denver, CO where my parents were living. When I was called up, the Board noting that I was a seminary student, gave me a 4-D deferment classification allowing me to finish my seminary training.

JT: So did you continue your art interests?

PF: I continued to have an interest in art, but only as a hobby. I tinkered with posters, signs, illustrations for Bible school materials, and charts. My high school art education was classical. By the time I was in Goshen, the so-called modern movement in art was the trend. I had problems understanding, especially, the abstract forms.

AR: When did you go to Wichita State?

PF: I went there in the in the summers of '56, 57, and the fall semester of '56. I left the University of Wichita to finish my graduate work at Fort Hays State College where I completed my graduate work for an M.S. in Art Education. The Department at Wichita was in the process of getting back onto its feet after losing the chairman of the department in a tragic accident that left two other art faculty members seriously injured, one being the ceramic instructor and the other the art historian. I felt fortunate to have three good instructors at Fort Hays who took a personal interest in me and whose work served as a catalyst for my creative endeavors.

The Fort Hays experience was interesting. I arrived early enough the first day of summer school allowing time for a breakfast in a small diner on the edge of the campus. The diner was full of summer school students. Conversation was lively and much of it related to one of the two professors teaching the course "Introduction to Graduate Study," which all beginning graduate students were required to take. I quickly learned that a particular instructor was one they vehemently despised. I heard one fellow say, "I would liked to have taken him out into the boonies and left him there for the coyotes." Those students who had taken the course were advising newcomers to take the course from the more favored teacher. Consequently, when I met with Dr. Joel Moss, chairman of the Art Department, I requested that I have Dr. Graber for the Introduction to Graduate Study course. He informed me that Graber's sections were full and that I would get along fine in the other instructor's section.

The first session with the "notorious" professor was intimidating. He lectured the class on his protocol for the class, which consisted of (1) signing up in advance at his office door for a 15 minute session, (2) you will not interrupt me with your questions while I am at coffee with faculty colleagues in the student cafeteria, (3) you will not call me on the telephone when I am at home and if you show up at my door, I will turn you away, and lastly, we were to prepare a bibliographical essay in preparation for our thesis and the subject had to be one that had not been written on within the last five years.

I had a hunch that the prof knew little or nothing about Mennonites and nothing about a relationship that Rembrandt had with Dutch Mennonites, so I decided to research "Rembrandt as a fellow traveler with the Mennonites." I knew Bethel College had some great resource materials in its Historical Library and that Irvin Horst, while in Amsterdam, had done some significant research on the artist in libraries and galleries in Holland. The subject was approved with much interest by the professor. When I submitted the paper, he called me into his office, invited me to be seated and began asking questions, wanting to know more about the Mennonite Church. At the end of the visit, he asked who I would be having on my thesis (performance thesis) committee and whether I would allow him to sit in with the committee when they would meet with me. I granted him the right to sit in. He said nothing during the session, but later informed me that he appreciated my paper and that it would be placed in the Forsyth Library with other papers from previous years. The Forsyth Library had only one copy of the Mennonite Quarterly Review. I had a fairly good number of MQR issues and decided to donate them to the Forsyth Library.

The session with the graduate committee was interesting. One of the five members was the Painting Instructor from the Art Department. In my exhibit I had a sculpture piece titled "Hiroshima". It triggered a heated exchange between the historian and the painter. To start with, the painter told me that my work was poor— and that she expected better work after three summers of work at Hays. She was known among students as a "red neck" and what she was basically reacting to was the sculpture titled "Hiroshima." Upon discovering her political reaction to the piece, the historian took over and for three fourths of session there was a heated exchange between the two professors. The session ended with very little time given to my exhibit.

JT: Going back a little ways to your seminary experience at Goshen, did you ever have any conversations with Harold Bender about the role of art and the church and so on?

PF: Not really. Harold was attracted to art that related in one manner or another to Anabaptist / Mennonite history. There was a Shank who created paintings of early Anabaptist leaders; these were frequently referred to in his history courses. I cannot recall hearing about Jacob van Ruisdael, a Dutch Mennonite painter. He did introduce the etchings in the Martyr's Mirror.

JT: Did you see connections between your art interests and your pastoral work?

PF: I think I began to see it when this country was in war with Viet Nam. Students during this time were becoming quite reactionary. Their absence in church attendance was noticed and of concern to both Student Services and the College Church pastors. Peter Wiebe was pastor of the college church at the time and John Lederach was chairman of the Board of Elders at the Church. A committee of college and church personnel was formed to plan a contemporary service that would appeal to students and younger folks in the congregation.

For the first service, a suggestion was made that I use the potters wheel in a presentation based on the 18th chapter of Jeremiah in which the prophet is told to go to the house of the potter to hear the word of the Lord. It was not the easiest thing to do, talk and concentrate on what the hands should be doing; but we managed to make four different colored forms—a white vessel, a red vessel, a yellow vessel and a black vessel. The white vessel was destroyed, slaked back into mud. The others were kept to be finished with a glaze. Following the service, individuals were asking whether they could purchase them. It was decided that they could be purchased and could be picked up the last Sunday prior to commencement. The black vessel was not picked up even though someone had spoken for it. We kept it in our home for the summer.

The first service in the fall was dealing with the subject of reconciliation. Since the black vessel had been rejected, I suggested that toward the end of Peter's sermon, I would get up from my place in the congregation and walk to the front and stand in front of Peter at the pulpit. There I would inform him that hearing his encouragement to the congregation to be accepting in our relationships with one another, I was disappointed that someone had spoken for the black vessel (sitting on a pedestal on the platform) and later rejected it when they could have picked it up. So I had come to destroy it.

Peter did not like the idea of destroying that particular vessel. It had become a significant symbol for what he and his wife Rita Mae had taken into their family. They had adopted a little African-American girl and the black vessel took on significant meaning for them. They wanted to exchange a piece they had acquired from me earlier for the black vessel but I felt it was important that the rejected piece should be the one we would break.

When Peter gave me the cue, I got up and walked to the front of the sanctuary, stood in front of Peter. He asked for an explanation of my presence before him. I replied something to the effect: "You have been encouraging all of us to be caring and accepting of each other in spite of our distractions. Do you see the vessel sitting over there? Someone last spring asked to have it but apparently rejected it for one reason or another. As its creator, I am here to destroy it." He informed me that he did not want it destroyed, and took the vessel out of my hands. I took it from him and said: "There must be something about the piece that is bad that the person requesting it has rejected it; I've come to destroy it!" I threw it down onto a slab of marble placed on the floor earlier. It broke with the sound of Gideon's vessels and there was absolute silence in the congregation for a few seconds that seemed like minutes.

At the end of the service, the janitor had nothing to pick up. Individuals in church that morning picked the pieces up; it would be interesting to know the purpose for doing so. I did get some interesting telephone calls after the service.

I was given the first Funk lectureship in the Visual Arts for the (Old) Mennonite Church. I created a sculpture form which I titled: "The Burning Bush" for the lectureship. It was created using laminated plywood, walnut wood, steel and old square nails salvaged from the First Mennonite Church in Hillsboro. A presentation relative to the piece was to be given at the three "Old" Mennonite colleges and to Mennonite congregations.

Following the service in the first congregation where I gave the presentation, a member came to me and said: "You know, Paul, you would have done yourself and us a favor if you would have stayed at home." That was a Saturday night and Sunday morning I was to give the presentation to another church. I hardly knew what to do. For some reason I had taken the potter's wheel along and some clay. I decided to junk the sculpture presentation and use the potter's wheel to tell my own spiritual pilgrimage. It had a positive response, to the extent that word about the presentation got around and other churches began extending invitations for the presentation. The presentation was given not only to churches but to public schools, Soil Conservation gatherings, civic groups and churches in other denominations for the next 11 or 12 years. When the wheel wore out, I decided it was time to stop.

JT: Did you find teaching here at Hesston that the students coming out of the "Old" Mennonite Church were as resistant as the church in general? Or did you find a difference of attitudes among students here?

PF: Students who came out of the public school system were generally ready and open to taking art courses. Some had taken some art while in high school. Those coming from the parochial (church) high schools were a little slower in venturing into the visual arts; but after taking a course or two, a few decided to pursue the visual arts as their major. I found the situation to be the same when I started teaching at Bethel. Now and then a student would tell me that their parents were opposed to them majoring in art, basically because they would never be able to support themselves. Several students who graduated with a major in art told me years later that they actually did better than their parents financially. I'm sure there were many who could not say that.

JT: Let's see, which years did you teach at Hesston?

PF: I started teaching at Hesston College in the fall of 1956, taught half time as I was taking classes at University of Wichita [now Wichita State University]. While attending Bethel College earlier I learned to know Robert Regier through Lena Waltner, professor of art there. When Lena was ready for retirement, J. Winfeld Fretz, acting President at Bethel, approached me about joining the faculty at Bethel College to teach art. Winfeld approached President Smith at Hesston whether there was a chance that they would share half my time with Bethel. Smith consented to let me teach half time at Bethel. However, I did not feel that I was qualified to handle the assignment alone, so I informed Winfeld that I would be willing to come if he could talk Robert Regier into teaching a night course each quarter. Bob consented to teach design and painting, so we both started at Bethel together and stayed until I retired from teaching in 1989. Bob enjoyed teaching and decided after a couple years to leave his work at General Conference Headquarter. He left Bethel for two years for Graduate School, after which he returned to assume Chairmanship of the Bethel Art Department.

Upon Robert's return to Bethel we decided that both of us would teach the art courses at Bethel and Hesston. Robert would be teaching basically the two dimensional courses and I would teach the three dimensional. We both taught the appreciation courses, one at Hesston and the other at Bethel. This arrangement was a benefit that neither of the colleges could have afforded. I have many fond memories of those thirty years of collaboration between the two colleges.

Bethel profited in several ways from the cooperative program, a significant one being that some of Hesston's art majors decided to take their last two years at Bethel College; something that was not too well accepted by a sister college of Hesston's.

There were a couple years when personnel from both institutions met periodically to explore ways in which the colleges could further cooperate. The Art Departments at both institutions had weakened the walls of separation between the two colleges.

I'm quick to say that those thirty years of teaching with Robert Regier were the best that I could ever ask for. If there were differences between us, I cannot remember what they might have been. We hung numerous exhibits, sometimes late at night, but I always went home grateful for the colleague I was privileged to work with. At retirement, it was hard leaving students but even harder leaving a colleague who contributed so much to my own artistic growth.

JT: Say a little about your post-retirement activities.

PF: Having read the book Passages, in the latter seventies, I decided it was time to begin preparing for retirement. I still wanted to continue teaching at Bethel where I could work with juniors and seniors, but felt that the time had come to leave Hesston College. I was aware that my leaving Hesston College would possibly bring an end to the cooperative program with Bethel College, and it did.

Bethel College continued to keep me on for half time until I retired from teaching in the spring of 1989.

I began retirement on a half time basis in a studio below a bakery at the corner of Randall and Main in Hesston. During the next eleven years part of my studio time was given up to serve on the pastoral team of the Hesston Mennonite Church. When able to work in the studio I continued to work with individual students, some high school and a couple college graduates who were wanting to get into the field of ceramics.

PF: Wilma and I had put our names in at Schowalter Villa about fifteen or twenty years prior to our move. In the summer of 2000 we decided the time had come to make the move. James Krehbiel had become the CEO. During an interterm he had been in one of my classes at Bethel; consequently he knew what my interests were and proceeded to show me a room and suggested that maybe I would be interested in using it as a studio. I was encouraged to offer a class or two and be open for people interested in watching a potter at work. I agreed to the offer.

Wilma sometimes feels that I spend entirely too much time in the studio, but when one is a potter, one learns that the clay dictates when you work with it once one has started a piece. Firings are critical and demand considerable attention for nine and sometimes ten hours, especially reduction glaze firings.

I enjoy the working with adults, mostly folks from neighboring towns as well as Hesston. Lately I have started a class for Villa employees which meets once a week. They come in at six in the evening, tired and wondering why they ever consented to take the class, but within fifteen minutes they are rejuvenated and having a great time exploring clay and procedures for shaping and decorating it.

AR: I'd like to know a little bit about how congregations have responded to abstract art pieces.

PF: It would be interesting for you to speak with some folks at Whitestone Mennonite Church. Prior to moving into town, the congregation was known as the Pennsylvania Mennonite Church, and was located near the East Lawn Cemetery. When they decided to build in town, Howard and Martha Hershberger came to me inquiring whether I would be willing to create a piece of sculpture for the chancel of the new church. Howard was obviously a respected and influential person in the congregation. He informed me that I had complete freedom in designing the work. My question to him was: "Are you sure the congregation is really ready for a three dimensional piece in their church? I fear there will be a lot of opposition for such a form." His answer was something to the effect: "I will handle the problem when it arises."

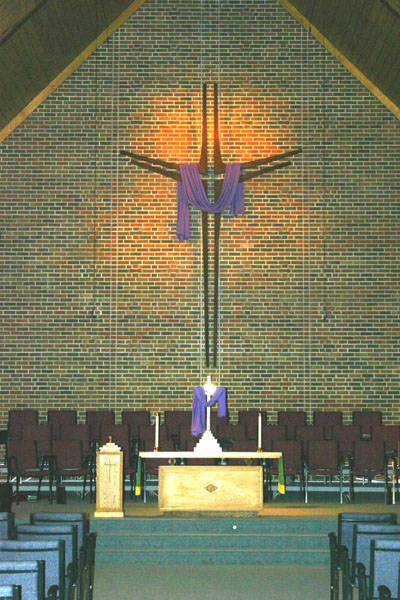

Chancel sculpture, 1964, Whitestone Mennonite

Church, Hesston, Kansas (photo by John D. Thiesen)

Going home for lunch one day, as I walked through the bird sanctuary, I observed clusters of large thorns on the trunk of a locust tree. They became the inspiration for what I eventually created. The composition consisted of three crosses, two of which were attached to each other and the third unattached to the two. The two attached symbolized a cross of repentance and the large one the cross of atonement. The single cross on the left symbolized the cross of rejection.

It was a Saturday night prior to the first service in the sanctuary when the sculpture was hung. A number of members were present helping get everything ready for the morning. When the pieces were finally installed, one member came to me and said: "What in the sam hill do you think you are doing to our church?" There was real disappointment and a tinge of anger in the question. I replied: "I sense you have some pretty strong feelings of disapproval. Will you share them with me? What is there about the pieces that you do not like?" He replied: "That just reminds me of a bunch of steers." I replied: "The horns of a steer. You are right on. You could not have given me a better interpretation. Tell me, if you got into a pen with a vicious steer or bull that began to charge you and you knew you would not be able to get out of that pen in time, how would the situation end up?" He replied: "I'd probably get gored to death", to which I replied: "You are right on; you would be crucified by the horns of the animal."

Some years later, the same individual told me that he would not want to see the sculpture removed from the sanctuary. Numerous others shared positive responses to the piece. Time is an important element for viewing art. First responses are seldom quality responses.

Chancel sculpture, 1972, Trinity Heights United Methodist Church,

Newton, Kansas (photo by John D. Thiesen)

A similar response is heard from members of the Trinity United Methodist Church in Newton, where I was commissioned to do a piece for their sanctuary. As they are currently preparing to build a new sanctuary, the congregation made it known to the building committee that they wanted the chancel sculpture placed on the chancel wall of the new sanctuary.

"The Parable of the Ten Virgins," ceramic relief, 10' x 8', Hesston

Mennonite Church (photo by John D. Thiesen)

The first piece of sculpture commissioned by the Hesston Mennonite Church was a clay relief: "Parable of the Ten Virgins," a 8 ft. wide by 4 ft. high relief. It apparently was well accepted for I never received any negative comments. Occasionally, wedding pictures were taken in front of the relief.

"Transformation," 2001, walnut, at Hesston

Mennonite Church (photo by John D. Thiesen)

Later on, more recently, the church asked me to do a piece symbolizing "Transformation." A walnut log was chosen for the piece. Out of it several shoots emerge and as they grow, they draw close together and then part, repeating the process for some distance when finally they merge into a ring with vertical fingers ascending together—a symbol of merging two conferences.

I was working on the piece in the wood shop of the Hesston Wellness Center. A number of people would stop, give their comments or raise questions, always curious to see the progress from one day to the next. One gentleman, retired farmer, stopped in, looked at the piece and said: "Guts, guts." I replied: "You mean intestines?" "Well, ya, guts." I don't know what he thought when he saw the piece on the platform one Sunday morning. One individual has repeatedly come to me to let me know he likes to enter the sanctuary early, focusing his attention on the piece and experiencing something new each time.

So in answer to your question, I have come to believe that as people allow themselves to be exposed to something new and endeavor to relate to the form, with time a compatible relationship emerges. It is similar to relationships we form with new neighbors. If we do not make an effort to learn to know each other, we will likely distance ourselves and disapprove of their presence. Out in India, as a Mennonite missionary kid, I never thought of the (Old) Mennonites and the General Conference Mennonites as being two different Mennonite castes. We all were Mennonites at Woodstock. In a real sense, we were merged!

The interview concluded with a walk to Friesen's outdoor workshop, where a sculpture was in process for the Dyck Arboretum.

(photos by John D. Thiesen)

Finished piece, "Keeper of the Ammonite,"

native limestone, installed at Dyck Arboretum

Notes

(All photos courtesy of Paul Friesen unless otherwise noted.)

1. See Lois Barrett, "Confident Because of the Call: Florence Cooprider Friesen (1887- )," in Full Circle: Stories of Mennonite Women, ed. Mary Lou Cummings (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1978), 82-86.

Bethel College fountain in preparation ca. 1967 (photo from Mennonite

Library and Archives photo collection)

Bethel College fountain in spring 2007 (photo by John D. Thiesen)

Chancel sculpture, 1970, Hesston United

Methodist Church (photo by John D. Thiesen)

"The Singleness of the Eye," 1981,

at Hesston College (photo by John D. Thiesen)

"Immigrant," 1993, palo santo wood, private owner

"View over Caleb's Hill," 1994, laminated walnut, in Bethel College Library (photo by

John D. Thiesen)

"Prairie Sentinel," 2000, osage orange, at Dyck

Arboretum, Hesston, Kansas (photo by John D. Thiesen)

"Maze of Scorpion Ridge," 2001?, wild cherry, private owner

"Pentecost," 2003, quebracho wood, private owner

"Soul Named Florence," black walnut, 2004,

at Newton Medical Center (photo by John D. Thiesen)

"South Wind," 2005, cherry, private owner

"Butterfly," 2006, quebracho, Paul Friesen

personal collection

"Prairie Landscape," 2006, walnut, at Hesston

College Library (photo by John D. Thiesen)

"Lidded Urn," stoneware, Paul Friesen personal collection

untitled, stoneware, Paul Friesen personal collection

untitled, stoneware, Maybee Foundation collection,

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Low fired earthenware

Saggar fired vase