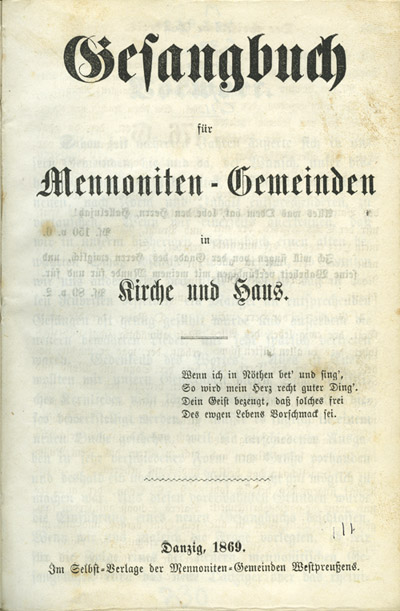

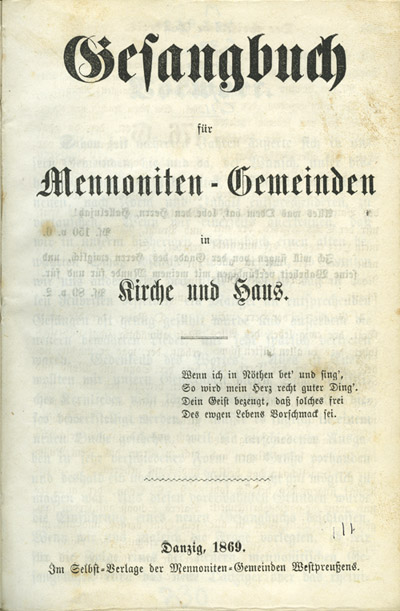

Title page of 1869 hymnal

Fall 2007

vol. 62 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

Fall 2007

vol. 62 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

Mark Jantzen is associate professor of history at Bethel College. He is co-editor of the recently published English translation of H. G. Mannhardt's The Danzig Mennonite Church. William Eash is professor of music at Bethel College.

The country faced wars on several different fronts. Public debates over the influence of military spending on politics became so viciously divisive that the government faced deadlock and even the possibility of shutting down. New draft legislation had been introduced multiple times and included specific proposals to strip away past accommodations for Mennonites as conscientious objectors. Some Mennonite leaders were deeply concerned that their people would not be ready for a draft while others thought the threat unimportant or overblown.

At a superficial level this description might seem to fit a post 9/11 United States. It also describes Prussia in the 1860s. This decade was particularly traumatic for the Mennonites of the Vistula Delta. Their country fought and won a war with Denmark in 1864 and won a second war two years later against the Austrian Empire. Volatile relations with neighboring France led to a third war in 1870, which Prussia again won. All three of these wars were fought to create a unified German nation-state, a feat achieved finally in 1871. The public debate and newly drawn political boundaries that resulted from these wars led in 1867 to the final revocation of Mennonites' exemption from the draft everywhere in Germany. Into this context the rural congregations of the Vistula Delta, near modern-day Gdask, Poland, in 1869 released a new hymnal entitled Gesangbuch für Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Kirche und Haus (Hymnal for Mennonite Congregations at Church and at Home).(3)

Title page of 1869 hymnal

One striking new rubric in the table of contents was "Love of Enemies." In a decade when political events forced Prussian Mennonites to think about "enemies" in immediate and practical terms, the selection and inclusion of three hymns under such a provocative heading constituted a theological response expressed in hymnody to the intense pressure on Mennonites to join the Prussian army and to find their primary identity in the German nation instead of the Mennonite church. In a setting that glorified wars of national unification and the political leaders who orchestrated them, the inclusion of "Love of Enemies" in a new hymnal went beyond being a theological and musical pronouncement. This act was also a political statement. Because none of these songs have previously been translated into English, an important hymnological voice in a dramatic debate has been lost to North American Mennonites.

Table of contents page of 1869 hymnal

showing "Feidesliebe"

The Vistula Delta was one of very few havens for sixteenth-century Anabaptists which remained relatively tolerant all the way through to the nineteenth century. Anabaptists fled here from waves of persecution in the Low Countries in the 1530s and 1560s and a few came from Switzerland and South Germany as well. By the late eighteenth century about a dozen congregations with a total population of well over 10,000 had emerged.(4) The transition to German from Dutch was completed at different speeds in different congregations. By 1767, however, the rural majority of Mennonites was ready for a German-language hymnal, Geistreiches Gesangbuch, because, as the foreword noted, the congregations were already teaching their youth and preaching in German.(5)

A political transition with far-reaching repercussions occurred only five years later in 1772 when much of the area was taken by Prussia from Poland in the First Partition of Poland. Most Mennonites were under Prussian rule after the Third Partition in 1795. The new rulers were better able to impose their will directly on their subjects than the Polish kings had been. The Hohenzollern dynasty that ruled Prussia was particularly interested in increasing state revenues and the size of their army. As a result, Mennonites were soon forced to pay higher and more regular fees to avoid military service and found themselves barred from buying additional real estate for farming or business or even buying a house from non-Mennonites unless they were willing to allow their sons to serve in the Prussian military. Thus beginning in 1788 a series of emigrations from the Vistula Delta to modern-day Ukraine ensued.(6)

Those Mennonites who remained in Prussia worked out a stable understanding with the Prussian government that released all Mennonites from military duty in exchange for an annual communal Mennonite tax and a moratorium on purchasing real estate. This equilibrium was shattered by events in Prussia in the 1860s.

At the outset of the decade, Prussia was locked in a constitutional crisis. Revolutionaries in 1848 had won the concession of a very limited constitution from the king. Liberals were forced to accept the king's absolute authority over the Prussian military in exchange for gaining the authority to approve all new taxes. When, however, the king and his minister of war, Albrecht von Roon, in 1860 asked for additional money and a new military service law in order to increase the size of the army, the parliament rejected their proposal unless they were allowed to control important aspects of military service. This King William I refused as an affront to his royal authority. By 1862 all cooperation between king and parliament had ceased. Revolution was in the air and William thought of abdicating.(7)

The day was saved for the Prussian monarchy when Otto von Bismarck, who had been posted to Paris as Prussia's ambassador, agreed to serve William as Prime Minister. Bismarck pledged to uphold the king's royal prerogatives and not the constitution. He immediately sharpened press censorship and prorogued the parliament, hoping to gain a more conservative body after new elections. He only succeeded in this goal after maneuvering Prussia into the two wars of the 1860s. After the 1866 war Bismarck annexed many of the smaller north German states that had sided with Austria in order to create a new North German Confederation. After a final war against France in 1870 this Confederation became the German Empire. The military victories of 1864 and 1866 so delighted nationalist sentiment in Prussia that Bismarck no longer needed to elect new parliamentarians to gain a majority in the Prussian parliament. Numerous former opponents now changed sides and formed a new party, the National Liberals, who together with conservatives backed Bismarck's policies. In 1867 the parliament legalized retroactively all of Bismarck's unconstitutional political activities.(8)

Bismarck wrote a new constitution for the North German Confederation, which established a parliament to administer the new state. One of their first items of business was to debate an inaugural law on military service. Only three exemptions to the draft were proposed: the sons of the Prussian royal family, who would, of course, served as important generals in any case; the sons of the defeated ruling families of the minor German states; and the sons of Mennonite families of the Vistula Delta. After considerable debate, the first two exemptions were approved while the third one was struck down. King William I signed this draft law into effect on November 8, 1867.(9)

The Mennonite leadership was shocked by this turn of events and quickly worked out a lobbying strategy to persuade the government to preserve their military exemption. A delegation of five Elders or leaders of congregations went to Berlin in October 1867 and again in February 1868. They met with King William I, his son the Crown Prince Frederick, representatives of both the House of Representatives and the House of Lords, and the majority of the Prussian cabinet ministers. This lobbying by Mennonite farmers of Prussia's top leaders resulted on several occasions in curious exchanges. At one point the War Minister, Albrecht von Roon, grabbed an Elder's lapel and demanded to know if Mennonites believed that he as a soldier could get into heaven. The Crown Prince, when informed by the Mennonites that they would emigrate to Russia if their exemption was revoked, suggested they should go elsewhere, as the draft would be introduced there soon as well. In an unusual display of Mennonite generosity, one of the Elders suggested to the king that they would gladly pay much higher taxes in exchange for maintaining the status quo. The result of all of this activity was that on March 3, 1868, the king signed a decree allowing Mennonites to serve in the army as noncombatants.(10)

This offer of compromise created a deep schism in the Mennonite community. Some advocated accepting military service outright or as noncombatants and using that service as leverage to end the special taxes and legal discrimination that Mennonites faced. A petition to parliament demanding full civil rights in exchange for accepting military service garnered almost 800 male Mennonites' signatures in 1868 and almost 1,300 in 1869. At the same time, over 1,800 Mennonites signed a counter-petition suggesting that they wanted to be stripped of their voting rights in exchange for retention of their exemption from military service. In the Heubuden congregation the issue finally led to an angry confrontation on Sunday, June 7, 1874, when Elder Gerhard Penner denied communion to church member Bernhard Fieguth, a freshly minted Prussian Mennonite soldier. In a case that went all the way to Prussia's High Court in Berlin, Penner's denial of communion to Fieguth was declared illegal and Penner was forced to pay a substantial fine.(11) Thus the wars Prussia fought sparked bitter squabbling among Prussia's Mennonites, raising new questions about where one's enemies were to be found. The 1869 Gesangbuch was thus produced in a setting of incipient church schism.

Gerhard Penner

Heubuden church

The desire for a new hymnal had been growing for a number of years. Already the foreword to the tenth and last Prussian edition of Geistreiches Gesangbuch in 1864 noted the print run was being held small since a new hymnal was being planned. This same year the constitutional crisis in Prussia reached its height and Prussia went to war with Denmark.(12) An official decision was taken in 1865 by the conference on Mennonite congregations in West Prussia to elect a commission that was charged with producing a new hymnal.(13)

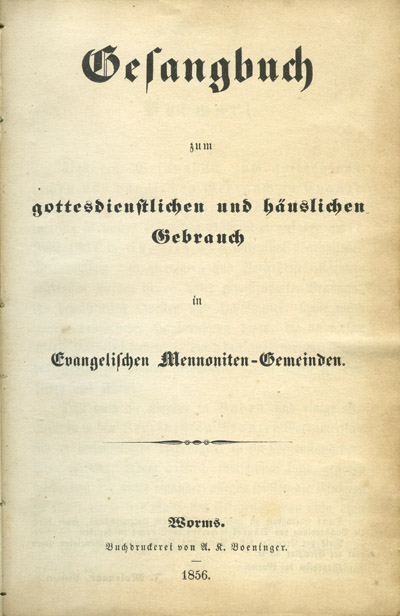

The rural congregations which sponsored this hymnal obviously rejected the simpler solution of adopting outright one of the two existing German Mennonite hymnals. South Germans had produced their first modern hymnal in 1832. Already in 1856 they released a third hymnal entitled Gesangbuch zum Gottesdienstlichen und häuslichen Gebrauch in Evangelischen Mennoniten Gemeinden (Hymnal for Church and Home Use in Protestant Mennonite Congregations).(14) This edition introduced a selection of three hymns entitled "Love of Enemies." Thus the rubric itself appears to be borrowed from here.

Title page of 1856 hymnal

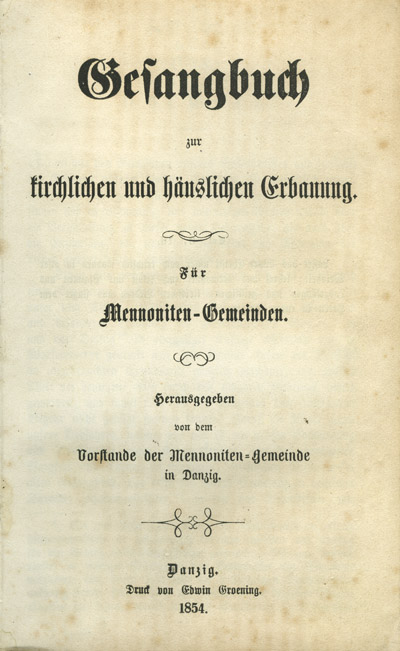

A more immediate option, it seems, would have been to use the hymnal produced in 1854 by the local, urban Danzig Mennonite church. Scholars have characterized the Danzig hymnal as more rationalistic and liturgical than that of the rural congregations.(15) In addition, it was also more patriotic, as it included sections on Christian government and the Fatherland. Lyrics included a prayer for God "to bless us by preserving our king on his throne."(16) The Danzig Mennonite church provided the intellectual arguments for accepting military service, so it is no surprise to find the tensions between more acculturated Mennonite soldiers and more traditional non-resistant Mennonites also reflected in the hymnals they produced.(17)

Title page of 1854 hymnal

The rural Mennonites of the Vistula Delta in 1869 ultimately opted for selected borrowing from other sources instead of a wholesale adoption of other group's hymnal. While the rubric "Love of Enemies" had been borrowed from the south Germans, the constellation of songs complied under it was new and unique to this hymnal.

The first song of the trio was also borrowed from the south Germans' 1856 Gesangbuch.(18) The lyrics of "Only Where Love Is" (Nur wo Lieb ist)(19) directly addressed the theological problem of hating one's enemies: "If you hate your enemy, know that thereby the kingdom of darkness has bound your spirit." Because both the author of these lyrics as well as the 1869 hymnal committee remain anonymous, there is no way to know for certain how or why this song were included in this hymnal. In adopting the hymn, the Prussians changed its tune. The south Germans sang it to the melody of O wie selig sind die Seelen, a melody also known up north as the Prussians sang four hymns in their 1767 Geistreiches Gesangbuch to this tune. Yet they chose to set the text in their new hymnal to Alles ist an Gottes Segen, a melody that was new to them but familiar to the Lutheran hymnody of their neighbors. The hymn with its original tune crossed the Atlantic when the 1856 south German hymnal was reprinted in the United States in 1873 as the first official hymnal of the newly formed General Conference Mennonite Church. It appeared for the last time in a new hymnal in the General Conference's 1890 Gesangbuch mit Noten.(20)

|

1. Nur wo Lieb ist, da ist Wahrheit; |

1. Only where love is can there be truth; |

|

2.Denke nicht, der Herzensprüfer |

2. Do not think the one who tests your heart cannot see past your words |

|

3. Nur die Sünde sollst du hassen, |

3.The sin alone you should hate, |

|

9. Willst mit göttlichen Gefühlen |

9. Do you wish to feel divine, |

The second song in this section, "Jesus, Since Your Blood Has Bought Me" (Jesu! Da du mich bekehret), was a completely new hymn for Mennonite hymnody. The text was by Johann Jacob Moser (1702-1785), who historians still consider important for his work in founding the modern German legal system. He worked as a law professor at the University of Tübingen, as President of the University of Frankfurt an der Oder and as legal counsel to the nobles of the south German state of Württemberg. In the latter capacity he resisted the absolutist demands of the Duke of Württemberg illegally to turn over money needed to finance Württemberg's participation in the Seven-Years' War (1756-63). The Duke had him imprisoned in 1759 without bringing charges or putting him on trial. After the war concluded, he was released in 1764, having won widespread acclaim as a political prisoner and as a defender of the rule of law.

Johann Jacob Moser

While in prison, he penned over 1,200 hymns, including the one Prussian Mennonites included in their 1869 Gesangbuch. Conservative Protestants known as Pietists celebrated the steadfast faith his hymns articulated.(21) Vistula Delta Mennonites were steeped in nineteenth-century Pietist literature and presumably picked up this hymn from there.(22) The tune, Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele, was by Johann Crüger and is better known as the tune to "Soul, adorn thyself with gladness."(23) The hymn was also included in the General Conference's 1890 Gesangbuch mit Noten and disappeared from Mennonite hymnody after that. Perhaps the fact that Moser penned the final line of this hymn as a political prisoner made the text seem practical and appealing to the embattled Mennonites of the 1860s: "Oh, when will my enemies become God's friends and also mine?"

|

1. Jesu! da du mich bekehret, |

1. Jesus, since your blood has bought me, |

|

2. Es ist deine Gnadengabe, |

2. It is your gift of mercy, |

|

3. Nun, laß auch in diesen Dingen |

3. So in these things allow |

|

4. Sondern noch in diesem Leben |

4. Better far in this life here |

The final hymn of this trio is the only one penned by a Mennonite. David Rothen (1805-1852) was born in Switzerland. He moved to the Palatinate and was baptized into the Mennonite congregation of Friedelsheim in 1830. He taught school nearby until he immigrated together with his wife Barbara in 1832 to the United States. In 1834 the couple settled near Bluffton, Ohio, where he continued to teach school until his death of typhoid at age 47.(24) His text, "Transfigured Bless'd Savior" (Verklärter Erlöser), first appeared in the 1832 south German Mennonite Gesangbuch. It was set to the tune Es glänzet der Christen from 1825 by J. H. Tscherlitzky. Rothen's hymn enjoyed wide circulation, appearing in the 1856 south German hymnal and the 1869 Prussian Gesangbuch, from whence it was taken up by the Russian Mennonites in their 1892 Gesangbuch.(25) The mislabeled "fifth edition" of this hymnal was published in 1929 in Canada for the 1920s immigrants.(26) In the United States, the song was included in the first General Conference hymnal, in the 1890 Gesangbuch mit Noten and in the last German-language hymnal of the Mennonite Church.(27) It was published in the General Conference's 1965 Gesangbuch der Mennoniten, used mostly in Canada and Latin American by German-speaking congregations.(28) It has appeared in every hymnal of the south German Mennonites from 1832 to 1978, only to be dropped from the 2004 German Mennonite Gesangbuch.(29) This hymn thus enjoyed the most longevity of the three. The translation provided here is in meter and rhyme, so the echoes of the dramatic 1860s encounter of the Prussian Mennonites with German nationalism can be heard again if this hymn finds new singers in a new land.

|

1. Verklärter Erlöser, |

1. Transfigured bless'd Savior, |

|

2. Nicht Freunden nur sollen wir Gutes erzeigen, |

2. Not alone to our friends ought we do what is good. |

|

4. Was thaten denn vormals die gläubigen Zeugen? |

4. What did then the faithful, true witnesses of old? |

|

5. O Heiland, auch uns gieb die göttlichen Triebe |

5. O Savior, sincere longing in our hearts please give |

1. This article was originally published in Sound in the Land: Essays on Mennonites and Music, edited by Maureen Epp and Carol Ann Weaver (Kitchener: Pandora Press, 2005): 50-63. Many thanks to C. Arnold Synder of Pandora Press for permission to republish the text here with minor alterations Thanks also to student assistants Victoria Eastes and Sam Schrag for locating music and biographical information used in this article and to Professor William Eash, Anne Buller, Miranda Crile, Margaret Penner, Scott Janzen, Chris Janzen, Amber Celestin, Kara Stucky Janzen, and Aaron Linscheid for bringing these hymns back to life in performances in Beatrice, Nebraska; Waterloo, Ontario; and North Newton, Kansas. The singers for the recordings linked to this article were Scott Janzen, Aaron Linscheid, Margaret Penner, Rachel Voth, Miranda Crile, and William Eash. Luke Schmidt was the sound technician and the recording was done at Bethel College Mennonite Church.

2. Mark Jantzen was responsible for the text and lyrics. William Eash produced the scores and the musical recording. Thanks also to Karen Schlabaugh and Richard Tirk for assistance with the scores.

3. (Danzig: Im Selbst-Verlage der Mennoniten-Gemeinden Westpreußens, 1869). This hymnal went through four editions to 1901, Cornelius Krahn, "Hymnology of the Mennonites of West and East Prussia, Danzig, and Russia," Mennonite Encyclopedia, 2:875-9.

4. For overviews of Mennonites in the Vistula Delta see Wilhelm Mannhardt, Die Wehrfreiheit der Altpreußischen Mennoniten (Marienburg: Selbstverlag der altpreußischen Mennonitengemeinden, 1863) and Horst Penner, Die Ost- und Westpreußischen Mennoniten, 2 vols. (Weierhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1978 and Kirchheimbolanden: Selbstverlag, 1987). English-language introductions are available in H. G. Mannhardt, The Danzig Mennonite Church: Its Origin and History from 1569-1919, ed. Mark Jantzen and John Thiesen, trans. Victor Doerksen (North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 2007), Peter J. Klassen, A Homeland for Strangers: An Introduction to Mennonites in Poland and Prussia (Fresno, CA: Center for Mennonite Brethren Studies, 1989) and Horst Penner, "West Prussia," Mennonite Encyclopedia, 4:920-6.

5. Gesangbuch in welchem eine Sammlung geistreicher Lieder befindlich, 10th ed. (Danzig: Edwin Groening, 1864), iv. The first edition was printed in Königsberg in 1767. On the influential history of this hymnal, see Peter Letkemann, "The Hymnody and Choral Music of Mennonites in Russia, 1789-1915" (Ph. D. diss., University of Toronto, 1985), 75-112 and "A Tale of Two Gesangbücher," in Preservings 18 (June 2001): 120-30 and Walter Jost, "The Hymn Tune Tradition of the General Conference Mennonite Church" (Ph. D. diss., University of Southern California, 1966), 96-9, 115-29, 158-164.

6. Penner, Mennoniten, 2:19-36, Mannhardt, Wehrfreiheit, 120-50, _Con-45A26BA61Mark Jantzen, "At Home in Germany? The Mennonites of the Vistula Delta and the Construction of a German National Identity, 1772-1880" (Ph. D. diss., University of Notre Dame, 2002), 35-110.

7. The centrality of the 1860s to German history is indicated in the structure of several influential surveys that break the history of nineteenth-century Germany at this date. See, for example, Thomas Nipperdey, Germany from Napoleon to Bismarck, 1800-1866 (Dublin: Gill Macmillan Ltd, 1996) and the Oxford History of Modern Europe series: James Sheehan, German History, 1770-1866 (Oxford: Claredon Press, 1989) and Gordon Craig, German History, 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, 1978). Hagen Schulze ends with 1867, The Course of German Nationalism: From Frederick the Great to Bismarck, 1763-1867 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991). On the political aspects of military service in the 1860s, see Gordon Craig, The Politics of the Prussian Army, 1640-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), 136-179, and Gerhard Ritter, The Sword and the Scepter: the Problem of Militarism in Germany, 4 vols. (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1969-1973), 1:123-58.

8. Craig, German History, 1-22.

9. Otto Pflanze, Bismarck and the Development of Germany, 3 vols., 2d ed (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 1:341-61. Jantzen, "At Home in Germany?" 319-24.

10. Peter Bartel, "Beschreibung der persönliche Bemühung der fünf Aeltesten bei den Hohen und Allerhöchsten Staatsmännern in Berlin um Wiederheraushelfung aus dem Reichsgesetz, worin der Reichstag uns Mennoniten am 9. November 1867 versetzt hat," Christlicher Gemeinde-Kalender 29 (1920): 70-9; Penner, Mennoniten, 2:69-79. A copy of the 1868 decree is reprinted in Penner, Mennoniten, 2:260.

11. Jantzen, "At Home in Germany?" 329-57.

12. 1864 Gesangbuch, 10th ed., viii.

13. Abraham Driedger, "Die Entwicklung des Gemeindegesanges unsern westpreußischen Gemeinden," Mennonitische Blätter, 78, no. 4 (April 1931): 32.

14. Published in Worms, this was a very influential hymnal in southern Germany, appearing in a third edition in 1950. Jost, "Hymn Tune Tradition," 61-73; Harold S. Bender, "Hymnology of the Swiss, French, and South German Mennonites," Mennonite Encyclopedia, 2: 872-3.

15. Letkemann, "Two Gesangbücher," 128-30; Jost, "Hymn Tune Tradition," 93-4.

16. Gesangbuch zur kirchlichen und häuslichen Erbauung für Mennoniten-Gemeinden, Danzig, 1854, hymn 588.

17. Jantzen, "At Home in Germany?" 291-301, 329-57; John D. Thiesen,. "First Duty of the Citizen: Mennonite Identity and Military Exemption in Prussia, 1848-1877," Mennonite Quarterly Review 72, no. 2 (April 1998): 161-87.

18. As hymn 434 there.

19. The translations of hymn texts and titles are my own. The nineteenth-century German spellings in the original have been retained. As a commentator at the Sound in the Land conference helpfully pointed out, the Vistula Delta congregations sang in unison at this time so four-part singing is not an accurate recreation of 1860s congregational singing. Even so, in 1898 the same congregations published a Choralbuch that would have made it possible for a small group or a choir to sing some of songs in this hymnal in four parts, Choralbuch zu den Melodieen des Gesangbuches für Mennoniten-Gemeinden, (Self-published, 1898).

20. Walter Hohmann, Outline in Hymnology with Emphasis on Mennonite Hymnology (North Newton, KS: Self-published, 1941), 53, 63; Jost, "Hymn Tune Tradition," 148-58, 164-77.

21. Reinhard Rürup, Johann Jacob Moser: Pietismus und Reform (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1965), 1-12; Andreas Gestrich, "Johann Jacob Moser als Politischer Gefangener," in Johann Jacob Moser: Politiker, Pietist, Publizist, Andreas Gestrich and Rainer Lächele, eds. (Karlsruhe: G. Braun Buchverlag, 2002).

22. Jantzen, "At Home in Germany?" 216-25.

23. This text and tune are number 473 in Hymnal: A Worship Book (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1992).

24. P. B. Amstutz, Historical Events of the Mennonites Settlement in Allen and Putnam Counties, Ohio, trans. Anne Konrad Dyck (Bluffton, OH: Swiss Community Historical Society, 1978), 42; Christian Neff and Ernst Crous, "David Rothen," Mennonitische Lexikon, 3:551.

25. See Hohmann, Hymnology, 53, 66.

26. Harold S. Bender, "Hymnology of the American Mennonites," Mennonite Encyclopedia, 2:883.

27. Hohmann, Hymnology, 53, 66. Martin E. Ressler, An Annotated Bibliography of Mennonite Hymnals and Songbooks 1742-1986 (Gordonville, PA, 1987), 35.

28. Gesangbuch der Mennoniten (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1965), hymn 598 under the rubric of Anabaptist songs (Täuferlieder).

29. Gesangbuch, 2d ed (Ludwigshafen: Konferenz der Süddeutschen Mennonitengemeinden e. V., 1978), hymn 419, under the heading of "Peace Witness" (Friedenszeugis). Its omission from the new German Mennonite hymnal used by the south Germans was reported in an August 4, 2004, e-mail to the author from Torsten Seefeldt, Vice-President of the Berlin Mennonite Church's board.