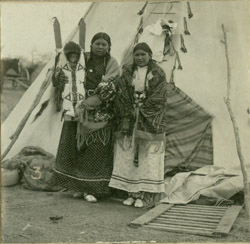

Figure 1: Nemeona, a faithful member up to

her death, of the Cheyenne church at

Cantonment, Oklahoma, c. 1910

September 2006

vol. 61 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2006

vol. 61 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

Kimberly D. Schmidt is associate professor of history and director of the Washington Community Scholars' Center of Eastern Mennonite University. She received her Ph.D. in American history from Binghamton University in 1995. Publications include the volume, "Strangers at Home: Amish and Mennonite Women in History," from The Johns Hopkins University Press. She lives in the Washington, DC area with two children.

In 1961, Lawrence Hart, Peace Chief of the Southern Cheyenne posed this question:

How soon shall we, if ever, reach the point of pacifism we once practiced long before the coming of the "spiders"?(1)

The term "spiders" refers to whites who were thought to have superior technical acuity—similar to a spider's abilities when measured against other inhabitants of the animal and insect kingdom. Hart's question could be developed in any number of ways but the focus of this article is on the women's history of the Southern Cheyenne. Initial research including interviews with six Cheyenne women and with Lawrence and Betty Hart led to rephrasing Hart's question: Did traditional Cheyenne women's culture contribute to peace traditions? Is it coincidental that women lost autonomy at same time that peace traditions were set aside and what might these two developments have to do with increasing contact with whites? During these years, from about 1820-1850, Cheyennes literally rode away from their roots as an earth lodge, agricultural people of trade in the upper Midwest, also known as the Middle Missouri. Previous to about the 1830s Cheyenne were often identified with other earth lodge, Algonquian speakers such as the Mandans and the Arikaras. By the 1830s -1850s, Cheyennes had made the transition to the plains and "equestrian nomadic culture," according to anthropologist, John H. Moore.(2) On the plains Cheyennes identified not with the Mandans and Arikaras and other farming tribes, but with nomadic hunting tribes such as the Sioux and Kiowa, whom they feared, and friends such as the Arapahoe.

On the plains, Cheyennes became known for their excellent horsemanship and fierce warfare. Women's status changed as their autonomy in the trade networks diminished and as a warrior culture, a response to white invasion, superseded the matrilocal, what Moore refers to as the uterine factions, of the tribe. After a prolonged struggle with the U.S. Army, which included the Massacre at Washita in 1868, the Southern Cheyennes were forced onto lands in Oklahoma.(3) The Oklahoma experience brought its own momentous changes to women's autonomy within the tribe. Mennonites, along with government schools and other groups, participated in diminishing women's culture. But the record is mixed. Some practices started by women missionaries may have enhanced women's status in the tribe.

Throughout this article women's power is addressed by analyzing their autonomy. Power does not refer to political advantage, status, or prestige, although women's status within the tribal guild structure is addressed. Rather, women with power are those who are autonomous, those who are capable of making autonomous life decisions. Within a worldwide, universal framework in which women are secondary to men, there are cultures in which women exercise various forms of autonomy whether this is expressed as economic self-sufficiency, the ability to choose one's life partner, reproductive choices, control over one's work or inheritance patterns to name a few.(4) Two additional terms, "uterine" and "agnatic," are borrowed from anthropology. Uterine refers to woman-centered, matrilocal and matrilineal "bands," meaning large family groups that camped together.(5) Agnatic refers to the male-centered bands, dog soldiers, and warrior societies, which reached their apex during the plains experience of Cheyennes. They were defined by their fierce warrior culture and by a patrilocal family structure.

In over 170 years of history, women-centered practices have not completely left the Southern Cheyenne culture. In spite of the fundamental changes wrought by years of hardship, warfare, more hardship and forced settlement, there are continuities one can trace from the earliest known historical accounts, written in the early 19th century, until today. Women have tenaciously guarded Cheyenne culture and some things have survived. This paper attempts to explain and trace a few of these continuities, starting with an explanation of women's autonomy in the earth lodge culture and continuing with an examination of how women's power within the tribe changed as a result of the plains experience and encounters with whites. An overview of women's experience with Mennonite missionary sewing groups concludes this general, broad brush-stroke approach to Southern Cheyenne women's history.

The stereotype most associated with Cheyenness is that of the "Fighting Cheyenne," the proud warrior in full battle dress.(6)

The Cheyenne warrior of the pre-reservation era embodies the stereotypical images of plains Indians. The warrior wore elaborate costumes made up of long eagle feather headdresses that were made to drape alongside the shanks of a horse at full gallop. Bright red face paint, breastplates made of bones and quills, beautifully painted shields, elaborately beaded moccasins and leggings and various weapons and beautifully beaded chokers and jewelry completed the warrior's ensemble. The warrior's pony wore special bridles which often consisted of rounded discs of mother-of-pearl or silver conchos traded from Mexico, as seen in ledger art from the day.(7) Scalps dangled from the jeweled bridles or were woven into the pony's tail. The finery and horsemanship of the tall, proud Cheyenne captured the imaginations of whites whom encountered them. Captain Charles King of the U.S. Army penned these phrases in 1880:

Even four years later, the memory brings the pulse up in my throat … warfare was never more beautiful than in you. On you come, your swift, agile ponies springing down the winding ravine, the rising sun gleaming on your trailing war bonnets, on silver armlets, necklace, gorget; on brilliant painted shield and beaded leggings; on naked body and beardless face, stained the most vivid vermillion. On you come, lance and rifle, pennon and feather glistening in the rare morning light, swaying in the wild grace of your peerless horsemanship.(8)

The preparations for war were time consuming. George Bird Grinnel, the prominent recorder of plains life and naturalist, wrote that the great warrior Roman Nose was often late to battles so meticulous were his pre-battle dress rituals. Roman Nose met his death when, not having time to prepare his battle medicine, a ritual which included full-body paint, he rode into the fray expecting to die.

But what of Cheyenne women?(9) We know that the stereotypes most often found in the early accounts, those of squaw and princess, obfuscate women's lives and work.(10) Recovering traditions, peaceful or otherwise, especially those associated with pre-literate women, is a difficult task. Women do not appear in many documents penned by whites and when they do the descriptions lack depth. Early white observers (all male) praised Cheyenne women for basically four things: good looks, chastity or virtuousness, productivity, and hospitality (see Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Nemeona, a faithful member up to

her death, of the Cheyenne church at

Cantonment, Oklahoma, c. 1910

Figure 2: A young Southern

Cheyenne mother and her papoose,

Oklahoma, 1910.

According to many early accounts, Cheyenne people were tall, strong, and dignified as seen in this typical description.

There is no finer race of men than these in North America and none superior in stature, excepting the Osages; scarcely a man in the tribe, full grown, who is less than six feet in height. Catlin [referring to artist George Catlin] considered "Wolf on the Hill" to be one of the noblest and more dignified Indians he met. The traders confirmed that opinion, saying the Cheyenne chief was a man of high honor and strict integrity.(11)

Stan Hoig writes that white observers recognized Cheyennes as, "having one of the highest Indian cultures on the plains. White explorers considered the Cheyenne mode of living to be cleaner, their women more chaste, and their sense of personal dignity stronger than most other tribes."(12) Cheyenne paid very close attention to personal hygiene, bathing even in frigid winter waters. Artist Frederick Remington was quite taken with Cheyenne women. "Indeed, some of them are quite as I imagine Pocahontas, Minnehaha, and the rest of the heroines of the race appeared."(13) According to art historian Michael Cowdry and anthropologist Virginia Peters, Cheyenne women wore makeup and dressed carefully, although their dress was much plainer than that of their brothers and fathers.(14) This is striking information when one considers that accounts of other Indian women usually described them as drudges, doing all the slave work of the men.

Among the plains tribes, Cheyenne women were recognized for their chastity.(15) Colonel Richard Irving Dodge wrote in 1882: "An unmarried woman must never be found alone, and it would be the height of impropriety for her to go anywhere with any man except her father."(16) Cheyenne maidens were not allowed to walk with any unrelated male and they were protected by other women in their families, their mother, aunts, older sisters, perhaps another expression of matrilocal culture (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Cheyenne girls holding a papoose

in a beaded Indian cradle, Oklahoma, 1910.

From Cheyenne Mission Souvenir (1911), p. 23.

Accounts of courtship reveal how important guarding female chastity was in the tribe and how difficult it was for a young Cheyenne man to catch the eye of his intended. According to George Bird Grinnell, most courting lasted from one to five years. The young man had to lay in wait for his intended to show up along a path and tug at her robe or try to catch her eye during her workday. Sometimes he would cover himself with a blanket and attempt to speak to her outside her lodge door. Courting was often done in secret under a blanket.(17)

The reticence of Cheyenne women lasted after the wedding ceremony. Couples were instructed not to consummate their marriage until ten days after the wedding. Some of Grinnell's male sources related that during this time it was usual for men to spend the whole night talking to their new brides. The ten-day period was seen as an essential way to get to know one another before engaging in sexual relations.(18)

Cheyenne women's birth rates must have been low, although this author has yet to investigate this aspect of Cheyenne women's lives.(19) One account observes that Cheyenne women were encouraged to give birth once every six years. Another account put the number at ten years. If a couple made it to ten years before the second child was attempted, a special ceremony was held to congratulate the couple on their restraint.(20) Before and after marriage, Cheyenne women were heralded as the most chaste of the plains Indians.

Cheyenne women, like many other tribal women, were noted to be hard workers. Colonel Dodge made these observations:

The pride of a good wife is in permitting her husband to do nothing for himself. She cooks his food, makes and mends his lodge and his clothing, dresses skins, butchers the game, dries the meat, goes after and saddles his horse.

When making a journey she strikes the lodge, packs the animals, cares for all the babies, and superintends the march, her lord and master, who left camp long before her, being far off in the front or flank looking after game.

On arriving at the camping place, she unpacks the animals, pitches the lodge, makes the beds, brings wood and water, and does everything that needs to be done, and when her husband returns from his hunt, is ready to take and unsaddle his horse.(21)

Early observers were horrified by the sight of men lounging by firesides while women incessantly toiled, often referring to women as slaves of their men. However, women's historians have shed new light on Indian women's plight. When compared to white women of their day, Cheyenne women had far more economic, political and personal autonomy. Anthropologist Nancy Lurie notes:

Whether the cosseted darling of the upper class or the toil-worn pioneer farm wife, the white woman was pitifully dependent through life on the whims and fortunes of one male, first a father and then a husband. Bereft of virtually any political rights, she also lacked the security of a tribe who would be committed to care for her if she were orphaned or widowed. Traditionally the white poor woman was left with the denigrating embarrassment of accepting charity.(22)

Cheyenne women held their own property, a tradition that survived the reservation era. Rodolphe Petter's second wife, Bertha Kinsinger Petter, in a biography of Vxzeta, a Northern Cheyenne woman, noted how she liked to explore "interesting spots of hills, valleys, springs and creeks," on her "favorite ponies, kept in the family as Vxzeta's own private property."(23) Horses were the main source of wealth on the plains. Owning horses secured a woman's economic standing (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Pavéna and her ponies. Oklahoma, 1910.

One pony was killed at her burial according to old

Indian custon. From Cheyenne Mission Souvenir

(1911), p. 33.

Cheyenne hospitality remains legendary. After the Mennonite mission at Cantonment burned in 1893, early missionaries Rodolphe and Maria Petter found themselves without a place to live. The missionaries were resourceful and fashioned a lodge of stretched canvas. They were able to travel, visiting from one family band to the next, Indian style (see Figure 5). In addition to living among Cheyennes for nine months and learning the language, Rodolphe recalled how they provided for his family:

As we sat outside eating a lunch, after our tent was put up, many Indian children stood about us, quietly watching us with great curiosity. Then Redmoon appeared on the scene, saying to them "Children, let these people in peace, a good Cheyenne should never gaze at somebody who is eating." A few hours later the hunters came back and a large piece of venison was brought to us. As long as we were there the Indians provided us with firewood, water, and meat.(24)

Figure 5: Marie Gerber Petter and daughter Olga visiting

Indians at their teepee, Oklahoma, 1899.

This notation is significant because water and firewood were not abundant on the plains. Women of the camps, perhaps the wife of Redmoon, must have made extra effort to provide the missionaries with these precious resources.

In an interview Lawrence Hart carefully explained that Cheyenne Peace Chiefs and their wives were held to high standards of hospitality.

In recent years you don't hear so much about it anymore but the word sanctuary.… in those days the chief's lodge was the sanctuary of the camp. An enemy, like a soldier or… a person from another tribe, an enemy tribe. If the sentinels saw someone coming toward a village and saw him heading for the village and then later observed him going toward the lodge of the Chief, he would be unmolested … that's where they would go. That would be their sanctuary while there… they were safe.… There's one teaching from an older woman, the wife of a chief. We were discussing responsibilities. She said that if someone came to the lodge, the Chief's lodge, for a piece of coal to take to their lodge to start their fires she said, "Do not allow that person to leave with only that coal. Give food if you can or material goods to take back."(25)

These four characteristics — cleanliness, chastity, productivity and hospitality — were valued within the matrilocal tribal structure which defined Cheyenne women's lives from the earliest recorded history.

Whites first encountered Cheyenne in the early 1800s. We know that Cheyenne lived in a manner very similar to the earth lodge tribes of the upper Midwest, also known as the Middle Missouri, and it is here that we find matrilocal and peace traditions in their fullest expression. Most of the information we have on women in the earth lodges comes from Virginia Bergman Peters' 1995 book, Women of Earth Lodges: Tribal Life on the Plains. (26) Like the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras, pre-1830 Cheyenne were by and large earth-lodge dwellers, traders, and practitioners of river-bottom agriculture. Although Peters does not address Cheyenne in her book, preferring to focus on the Mandans and Arikaras, we can infer from two additional sources, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) and John Moore, that culturally, at least before approximately 1830 to 1850, Cheyenne were very much like other earth lodge dwellers.(27) Like other anthropologists, Moore groups Cheyennes with the earth lodge tribes.(28)

Documented by Moore as well as Peters, we know that Middle Missouri native people hunted buffalo and other game on foot and practiced a form of agriculture wherein the tough prairie sod was ignored in preference for the much easier to farm river bottom soil. One authoritative source comes to us from the letters of George Bent, the son of a Cheyenne chief's daughter and a white trader, who is considered to be one of the first historians of Cheyennes. His words are summarized from his letters by Lincoln B. Faller:

The oldest living Cheyennes remember their parents and grandparents…still lived by lakes, grew corn and built canoes, ate fish, ducks, even skunks, when, not yet great warriors, they lived in constant fear of attack by their enemies. Then, pushed by those enemies out onto the plains, they lived first in settled villages of earthen houses along a series of rivers and still grew corn, before, finally, they began to hunt buffalo, to live in tipis, when dogs were still their only beasts of burden, before they acquired horses and their men became great hunters and warriors, their women fine dressers of buffalo skins.(29)

Cheyenne women's farming and trade activities were documented by French traders as early as 1802, previous to the Lewis and Clark expedition.(30) Women's agricultural productivity enhanced their status and autonomy as traders. Writing about the Mandan, Peters notes:

The single most important factor in village society was the surplus of corn that the women produced. Their corn was the basis of the Plains trade network and the source of all the village tribes' wealth; it was the foundation on which their society was built and around which it was structured.(31)

One early observer, editor Elliot Coues, observed that at the turn of the nineteenth century Cheyennes

were successful middlemen in the Plains trade network, profiting from the exchange of horses traded from the south by Kiowas, and European goods, including firearms, traded from the northeast by Hidatsas and Mandans. Cheyenne women produced distinctive, high quality buffalo robes embroidered in narrow stripes of porcupine quillwork, which were coveted and traded for by all their neighbors.(32)

That buffalo robes were counted as valuable property can be ascertained from George Custer's account of property destroyed during the "Battle of the Washita." After the massacre he enumerated having destroyed "573 tanned buffalo robes, many decorated."(33) It has been estimated that each robe represented at least seventy women hours of work.(34) A decorated robe could take up to a year to finish.(35)

As with other native groups, women's productivity and virtue were linked. According to Mary Jane Schneider in her examination of Sioux women, it was important for a young woman to stay busy. "The girl who tended to her quilling was too busy to get into trouble with men and would make a good marriage."(36) Royal B. Hassrick writing about Sioux noted that

Girls began early to learn the skills necessary to becoming a good wife and virtuous woman. Girls who could quill and bead, who knew how to prepare hides, and who were good cooks were recognized as potentially good wives.… Such a girl would attract fine young men of the best families, who would bring many gifts and horses as her bride-price; she would bestow honor on her family.(37)

As with the Sioux, Cheyenne women were prized for their bead and quillwork. Art historian Winfield Coleman has researched Cheyenne women's sewing societies wherein young women sought admittance by offering gifts to older female teachers.

Its members were refered [sic] to as moneneheo, the Selected Ones, indicative of their high status. The society had both a religious nature and social and economic importance to the tribe and to the women in particular. This powerful society explicitly defined aspects of wealth and status, and reinforced the importance of gift exchange and uterine affiliations. As with any shamanic guild, members had to apply for admittance, and were accepted only if they met strict criteria, which included, but were not limited to high artistic and moral standards.(38)

Rodolphe Petter described these women's societies among the Northern Cheyenne:

The women have also their own organizations for dancing, healing, and certain work requiring special women's skill, as in tanning, beading, ornamental work and tent making. These industrial "guilds" are called Chosen-women, and the members are specialists in Indian womens' [sic] work. The leader of each gild [sic] is an expert in her art and admission to the society is gained by expensive presents and feasts. The initiate is taught technical terms with all the hidden symbolism od [sic] designs.(39)

Admittance into a society such as the Selected Ones or Chosen Women offered young Cheyenne women many forms of autonomy not only by bestowing honor on her family, but the chance to learn a skill that was highly valued and could be used to create items for trade, as Mary Jane Schneider noted in her work on the Sioux. "Excellence in craftwork brought prestige and wealth to the woman and her family."(40)

Like the Mandan and Arikaras, Cheyennes were matrilocal and matrilineal. Young men eagerly sought marriage for it was through the female line and family reputation that prestige was determined. The young couple set up housekeeping either in the bride's mother's lodge or in a lodge next door. It was entirely normal for a woman to live her whole life in her mother's lodge, along with her sisters and their husbands and children. Sons-in-law were to have ultimate respect for their wife's mother. So strong were the matrilocal practices that sons-in-laws did not speak to their wife's mother until they had proven themselves worthy, usually by way of warfare. Grinnell notes that sons-in-law would present mothers-in-law with scalps obtained during battle, after which the mother-in-law would honor the son-in-law by publicly proclaiming his deeds of bravery and presenting to him an elaborately quilled and embroidered buffalo robe, estimated by Grinnell to contain perhaps a year's worth of labor.(41)

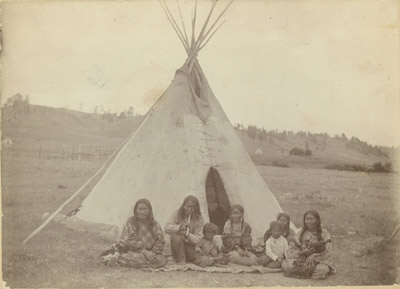

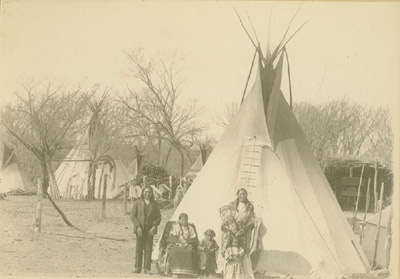

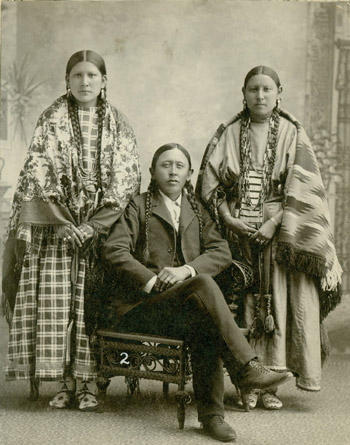

When a young man married, he often sought the companionship of not one woman but a family of sisters (see Figures 6-9). A common practice among earth lodge people and well documented among Cheyennes was "sororal polygyny" or marriage to sisters, usually two or three. Moore cites the advent of sororal polygyny to the rise in the trade of buffalo robes. By the mid-nineteenth century buffalo robe production had swung into high gear, fueled by the demand for carriage robes in large eastern cities.

The increasing importance of buffalo robes in trade had profound consequences for Cheyenne families. Because the robes embodied a huge amount of women's work, polygynous families grew up that were organized around a group of co-wives who were also co-workers and sisters to one another.… It was council chiefs who became the focus of this trade, and it was they who were most often polygynous. In fact, the chief's domestic household centered on his role as a trader and his wives' roles as producers of robes.(42)

Figures 6-9: These pictures from 1890 to 1910 reveal that even if Cheyennes no longer practiced sororal polygyny, family structures included more than one adult female, perhaps a sister to the wife?

Figure 6: Strong Left Hand and family, Montana, 1890.

Figure 7: Magpie (Kaovess) and family, Cantonment, Oklahoma, 1910.

From Cheyenne Mission Souvenir (1911), p. 15.

Figure 8: Redbird and family, Cantonment, Oklahoma, 1910.

From Cheyenne Mission Souvenir (1911), p. 13.

Figure 9: The picture was listed as "Robert Sandhill, wife and

sister," Oklahoma, 1910. Is the sister his sister or her sister?

If the sister is her sister, it is evidence of a remnant of sororal

polygyny or of matrilocal culture in which adult sisters shared

family life and lived in the same household.

However, Peters work on sororal polygyny among earth lodge tribes predates Moore's explanations. She noted how the Middle Missouri tribes practiced sororal polygyny because women who lived together and worked together often married together. Peters notes that Middle Missouri women worked together in family groupings on land they co-owed with their sisters, mothers, and other female relatives, just as women owned the lodge in which they lived, and raised their children together. Children formed "nisson" kinship networks or groups of same generation cousins who were most often raised as siblings.(43) Peters also noted how because of a higher male death rate primarily because of hunting and warfare, women in Middle Missouri tribes outnumbered men by a ratio of three to one. According to Peters, patterns of work, wealth distribution, child rearing, and the fact that men experienced higher death rates gave rise to sororal polygyny before the rise of the buffalo robe trade.

However, with the growing trade in buffalo robes, Cheyenne women's skills at robe making were valuable indeed. Although the practice of sororal polygyny predates the advent of what one might call the "mass marketing" of buffalo robes to cities in the East, the increased trade marked a definitive turning point in the women's history of the Southern Cheyenne. Turning buffalo hides into robes was a time consuming task and women worked in gangs or large groups, some scraping the hides, others tanning the hides, and still others doing the finish work and decorating the robes. Tanners were especially valued. Among Cheyennes only a post-menopausal woman, highly trained in the religious ceremonies and known as an excellent tanner could tan the white buffalo robes used for ceremonies. Among the Sioux, the honor went to a young virginal woman. The work of turning hide into robe was arduous and lengthy but was also recognized in the community as potentially sacred work, and if not sacred, at least very good for trade and welfare.

Most American school children are taught that the demise of the buffalo herds spelled an end to tribal life and culture. Scholars have found that access to water and grassland on the semi-arid plains was also critical to the survival of the tribes. Because of their ecological dependencies, Cheyennes were especially vulnerable to the U.S. Army during the cold months when they were forced to break up into small bands to winter along well-timbered river bottoms. The U.S. Army exploited this knowledge and the winter campaigns of Custer, Sheridan, Chivington and others were not accidental. While the severe reduction of buffalo herds dealt a terrible blow to Cheyenne it was not the sole reason the Cheyenne faltered. White encroachment brought environmental destruction at a shockingly early date. Cheyenne whose culture and livelihood depended on the natural environment suffered as a result (see Figure 10).(44)

Figure 10: Buffalo bones piled at El Reno, Oklahoma, 1889-1890, an

indication of the slaughter of buffalo herds on the Oklahoma plains.

The reduction of surface water, buffalo herds, and timber all affected long-standing Cheyenne social and political structures—including matrilocal structures. Instead of hunting, warrior societies, also known as dog soldiers, were reduced to raiding to provide for the bands and, not coincidentally, women paid a price. The old matrilineal kinship networks were turned upside down when women were required to live with their husband's band. Moore writes that Dog Soldiers were not interested in men marrying into women's bands, an act that would limit the number of warriors on hand. But women were opposed to agnatic or male-dominated factions, preferring to remain in their uterine, matrilocal groups. Moore speculates that in Black Kettle's uterine band, the ratio of women and children to men was higher than in the dog soldier agnatic bands. After the Sand Creek massacre, dog soldiers split from Black Kettle and within a few months completely did away with uterine, matrilocal practices. In the words of George Bent, "The Dog Soldier men dropped the old custom by which a man, when he married, went to live in the camp of his wife's band. They brought their wives home to their own."(45) But many women rejected the dog soldiers, to emphasize the point that they preferred the uterine culture of their ancestors. In an effort to control women's choices, dog soldiers put reluctant women "out on the prairie," a term that refers to gang rape as a means of coercing women into marriage.(46) Ultimately dog soldier resistance against whites and their attempts to save their way of life failed and Cheyennes were forced into the reservation system.

In spite of these hardships, women held on as best they could to some uterine practices. One of the clearest examples of a cultural survivalism is found, oddly enough, in the sewing circle societies, sponsored by Mennonite missionaries. The history of Indians and missionaries is replete with examples of how Christianity destroyed culture and personhood. Indeed, during his keynote address "The Christian Faith and Indian Cultural Survival," presented at the "Journey from Darlington" conference, Clyde Ellis argued for a nuanced history of Christian interaction with native people. In some cases, Native people embraced aspects of Christianity, incorporating their traditions with Christian traditions. Perhaps Christian missionaries unwittingly helped preserve native culture in the face of massive white cultural hegemony.(47) This may be one example of how Christian encroachment, as found in Mennonite expressions, may have helped to preserve at least a few aspects of Cheyenne culture.

The notion of a group of Mennonite women gathered to sew and talk with one another should be familiar to readers of Mennonite Life. There is a long standing tradition of women getting together to sew and support one another within the Mennonite church, just as there is a long standing tradition of Cheyenne women's sewing circles, the Selected Ones, who brought status and prestige to their families and autonomy to themselves through their sewing and bead work. Although there is no evidence of an missionary appreciation of Cheyenne women's chastity and productivity, surely these characteristics were lauded by early missionaries.

Rodolphe and Maria Petter from Switzerland worked as one of the earliest General Conference missionary couples among Southern Cheyennes. Other missionaries had preceded the Petters on the mission field in Oklahoma. It is with Maria, though, that we find the earliest evidence of a sewing circle that met regularly.

The written record of Maria Petter's sewing circles among Southern Cheyennes is sparse. From Rodolphe Petter's Reminiscences comes this description in 1893:

During an afternoon each week my dear wife had a sewing class for the Indian women who were anxious to make quilts and also little girls' dresses, like the one sent to their children by the sewing circles of our churches in the States.(48)

In addition to this meager record there is at least one picture of Maria's sewing circles from Oklahoma (see Figure 11). We also know that sewing circles were considered important to the work of the missionaries. Before reaching Oklahoma, Rodolphe and Maria made a few stops in Ohio, Indiana, and Kansas. The purpose of these visits was to learn English and build support for the missionary work. In 1890, Rodolphe's diary records Maria's preaching activities at a sewing circle amid visits and general community involvement.

November 6 and 7, 1890. These days were tranquil. We visited a brother of Sprunger. On Wednesday, they had a Temperance meeting. But there was not much life. All was cold. My dear angel spoke at the Sweing [sic] Circle on the dry bones, Ezekiel 37, with its application for Israel, the heathen world, then for the Christians.(49)

Figure 11: "Sewing class of Mrs. Marie Petter," Cantonment,

Oklahoma, 1900. (General Conference Mennonite Missions of

the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Tribes of Oklahoma in Pictures

1880-1935, Mrs. G. A. Linscheid, p. 19).

As an aside, it should come as no surprise that before the turn of the twentieth century we find Maria Petter preaching. She preached ninety to one hundred years before women were accepted into preaching positions in the broader Mennonite church. It has been well documented that Mennonite women exercised leadership gifts on the mission field that were denied to them in their home churches.(50) In addition to offering women like Maria leadership opportunities, sewing circles among the Southern Cheyenne may have helped them to reclaim a modicum of Cheyenne women's tribal status and autonomy.

By 1930 women's sewing groups were well established as can be seen from this reference: "The men at Hammon will have to do some more organizing to keep up with the women. The women not only have a sewing society but also a Chicken Club and a Garden Club."(51)

The main source we have for Southern Cheyenne women's sewing societies comes to us in the form of a small booklet, the "Star Mission Club minutes book" of the Mennonite church in Clinton, Oklahoma. The booklet states that, "The Mennonite Mission Star Club was organized at Soar Woman's Allotment in the month of August 1939."(52) This was well after Maria and Rodolphe had left Oklahoma to continue their mission work among the Northern Cheyenne in Montana. The mission club formally met for eight years, from August 1939 to December 1947. During those years, between five and fifteen women met at least once a month and as often as twice a week to sew quilt tops, dresses for girls, tea towels, and lunch cloths. One learns from the Cheyenne Arapahoe Messenger, a newsletter published by the Workers Conference of the General Conference missionaries in Oklahoma, that by the late 1930s a number of Mission Clubs were established.

As with women's work during the earth lodge years and on the plains, women worked in large groups. Pictures from early sewing circles in both Southern and Northern Cheyenne tribes show large groups of women seated on the ground, either inside or outside the church, attending to their sewing (see Figure 12). Women brought their babies and taught their daughters to sew. Women were in control over their production and used the proceeds from quilt sales, lotteries, auctions, and offerings as they saw fit. The work was woman-centered and woman directed. According to the Star Mission Club minutes book, during the first few months missionary J. B. Ediger gave the devotions but after March 1940 he did not attend and let the women run their own services. The women started each sewing circle meeting with a short service such as the following:

Figure 12: Cheyenne women quilting, Lame Deer,

Montana, 1961.

The fact that the meetings were woman-run is not a minor point. In one of the first scholarly articles to examine women's place in the Mennonite church, Sharon Kingelsmith found that the Mennonite Women's Missionary Society was forced to disband after they raised more money than the all-male Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities. Before disbanding, the society was taken over by the husbands of the members in the hopes that the men could control female decision-making.(54) The Star Mission Club did not have to worry about male take-over. They differed from other Mennonite groups in that women ran the show, free from male interference in decision-making or budgetary choices.

Another key difference was that Cheyenne women were not making layettes, quilts, or Christmas bundles to send overseas. Instead, Star Mission Club members were deeply concerned about the welfare of local Cheyenne people and others in the community. In an e-mail message, Lawrence Hart explained, "The Star Mission Club helped all Cheyenne, or Arapaho, irregardless of whether they were Mennonite. We saw this still practiced when we got here [in 1963]. One of the activities that was a good ministry was the making of layettes, given to new mothers at the Clinton Indian hospital, as an example."(55) The Star Mission Club provided a way for women to assert themselves in the community. They had a legitimate place in the community, one that was approved of by the patriarchal Mennonite church but also drew upon the much older Selected Ones tradition.

Figure 13: Star Mission Club women with quilt; left to right, Ramona

Hart, Blanche Hart Whiteshield, Angie Old Bear, Clinton, Oklahoma,

1960.

The group provided a venue for women who wished to serve. Much of what the Mission Club did during these years can be described as benevolent or charitable work. For example, at their second meeting they seemingly made spontaneous plans to visit a sick friend.

We immediately made plans to go and visit and cheer Bear Woman and found her to be a very sick woman. Held a short service at her home and found in need of medical attention. Held a special collection for her. Mrs. Ediger, Mrs. Burns and Mrs. Sarah Yellow Bull each gave .20 and we gave what dues we collected and also our Love offering. We found her without groceries and Mary Heap of Birds and Alice Heap of Birds each were to bring her something a day or so later.(56)

Two months later, the Star Mission Club held an offering to retire Bear Woman's medical expenses.(57) It was not unusual for the Mission Club to pay for groceries or to take prepared food to the elderly or sick. Their visits often started with a short program that could include singing, prayer, and scripture verses.

Additional cultural continuities can be found in giveaways, fundraisers for church and local camps, and hospitality sponsored by the Mission Club. They sponsored the Cheyenne custom of "giveaways" by giving quilts to those who were recognized as being in need. Sewing raised money for the group and they determined how to spend it. Women from the best families participated in the club. The roster and pictorial evidence is replete with high status family names such as Hart, Heap of Birds, and Whiteshield. Can one argue that the Star Mission Club allowed women a modicum of autonomy? Of course the prestige and status associated with the Club was not on the scale of the nineteenth century Selected Ones. Young women did not vie to gain admission to the society, nor did the quilts made by the club produce wealth for their families. However, Mission Club women were able to make decisions autonomous from male control and their charitable work was valued highly in the community and brought them visibility.

In an interesting development, local government officials heartily approved of sewing circles. It is doubtful that these officials would make connections between women's Sewing Circles of the twentieth century and the beading, painting, and tanning moneneheo, or Selected Ones of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Sewing was an acceptable activity for women; it was taught at the government schools and supposedly acculturated young girls into a white Christian culture that emphasized productivity, as the following quote about a government school reveals:

The closing exercises at each school consisted in contests in team currying, harnessing, driving, backing, turning and plowing and in milking, by boys. For girls there were contests in cooking, darning, mending, bed making, room tidying, butter making, etc.(58)

The Cheyenne Arapahoe Messenger noted how government workers supplied the Mennonite sewing circles with material:

Whenever Mrs. Tommie Worth (we do not remember her official title but shall call her home Demonstration Agent) meets with the Women's Clubs these days she has with her a large bundle of army coats and a basket full of patterns of just about all kinds and sizes. Each member can have as many coats as she will work up into clothes for her family. And our women make good use of this splendid opportunity. We can easily understand Mrs. Worth's enthusiasm under such circumstances. But men better not happen to be present when these women are busy as ants ripping seams with safety razor blades unless they want to help. We know.(59)

This was written by missionary G.A. Linscheid and in addition to describing relations between the paid government worker and Mennonite sewing societies, he hints at the reluctance of women to accept men into their fellowship. The quote also points to the variety of sources women had for materials. The Mission Clubs provided a way to gain much needed supplies from the Mennonite church, in the form of quilt tops, thread, money, and Christmas bundles. However, according to the newsletter Missionary News and Notes, the Women's Missionary Association eventually tired of sewing circles and deemed it important to stop sending supplies to the missions:

One great change that has taken place in our work during the past term was that the sewing for the mission stations decreased very rapidly….Suffice it to say here that most of the missionaries have come to the conclusion that too much giving makes "rice Christians", or dependent Christians who feel that they have a right to expect some material reward for becoming Christians.(60)

Christmas bundles and offerings to the Indian missions in Oklahoma and Montana continued but according to published records the contributions diminished every year. In spite of diminishing support from the Women's Missionary Association, it is clear from pictorial evidence that Cheyenne Mission Clubs lasted until at least until the 1970s.

To get back to Lawrence's question, Will Cheyennes ever recall the pacifist traditions that preceded the coming of the spiders? In spite of these strong uterine preferences, legacies from an earlier era, agnatic values are present. It was not uncommon for the women I interviewed to have participated in the armed services, such as Lenora Hart Holliman who joined the Navy after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.(61)

Others had husbands with service records. Cheyennes, like many tribes, make a point of honoring their veterans and mothers of service men and women during pow wows and parades. It is likely that the armed services offer economic security in an area where jobs are scarce.

One cannot turn back the clock but uterine cultural practices have survived. In many of the interviews I heard references to Cheyenne women's cultural practices. Some of these practices may help to reclaim that past wherein uterine, matrilocal values are elevated in preference to the warrior culture of the dog societies. Uterine traditions from the past are long hidden or lost and must, in many cases, be reinvented.

Naming ceremonies in which the eldest matriarch selects a name for the newborn child seems to be making a comeback. Informants talked of passing on Cheyenne ways from elder women to younger women usually during the younger woman's teen years. (62) Beadwork is valued and is taught alongside the Cheyenne language in local schools.

Like other American families, Cheyenne families are mobile and have become more and more fragmented but this author was surprised by some informants who told me that many of their family members live on the same block in the small Cheyenne towns. This practice could be ascribed to economic hard times or shortages in housing. Perhaps young couples move in with family members until they can provide for themselves. But the links to place are strong. Even those who have little to no lived experience in the town of their grandparents are still identified as being from that place. Connie Hart Yellowman explained that although she never lived in Hammon she is identified as a person from Hammon:

The Harts come from Hammon. If you say you're a Hart then they say, "Oh you're from Hammon" even though I never lived there. My brother never lived in Hammon but it was always the main thing, "Oh you're from Hammon, you're the Harts from Hammon." It was interesting how where people were located in the 1800s when the allotments were assigned and that's basically, even when we were young, 100 years later, that was where you were from.(63)

In addition to identifying oneself through family clan and place, family lineage is still traced through the female line. This was made clear to me when a hotel clerk interrupted my interview with Lawrence Hart to ask, "Now who would your kin be?" Lawrence answered "Bertha Heap-of-Birds." I experienced a little jolt as I was expecting him to say Homer Hart or some other male name. The clerk knew Bertha Heap-of-Birds and an interesting exchange followed about some of the women in Lawrence's family.

The concept of staying close to one's parents, especially one's mother's family, is still strong among those whom I interviewed and the tradition of the son-in-law honoring the mother-in-law by not talking to her is still practiced, as Margie Pewo related during her interview.

[ My daughter] married a full blood Cheyenne and he really believes, he comes from line of chiefs, and we still practice the old tradition. You know a son-in-law and a mother-in-law don't talk to each other. He practices that so do I. He has the respect [emphasis hers] for me.(64)

Hospitality and giveaways are two such venerable traditions that lend themselves well to pacifist traditions, not only of Cheyennes, but also of the Mennonite spiders as well. Margie Pewo spoke of how as a chief's wife she is expected to give what she can to those in need, even though she readily admitted that she and her husband are not well off.

Even before he became a chief we never ever turned anybody down. I was brought up to be kind to people and they ask for something, if you got it, give it to them. People have come up and ask us for help even though our finances are limited.… People know it here in Hammon.(65)

Gift exchanges are common. Betty Hart sent every woman I interviewed parcels of cloth. Perhaps these female-centered traditions and others yet to be invented will help Cheyennes reclaim their peaceful past.

Much appreciation to Raylene Hinz Penner and Betty Hart for suggesting that I work on the Star Mission Club and to Lawrence and Betty Hart for assisting with research, facilitating interview appointments and pointing me in the right direction, literally at times. The staff at the Mennonite Library and Archives, John Thiesen and James Lynch, were very helpful. This research was made possible by a summer research grant from Eastern Mennonite University.

1. Lawrence H. Hart. "Why the Doctrine of Non-Resistance Has Failed to Appeal to the Cheyenne Indian." (unpublished paper, Bethel College, 1961).

2. See John H. Moore, The Cheyenne Nation: A Social and Demographic History, (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1987): 139.

3. I am deliberately using the term "massacre" instead of 'battle." Black Kettle's band of Southern Cheyenne was peaceful. For an assessment of Black Kettle's attempts at peace see Thom Hatch, Black Kettle: The Cheyenne Chief Who Sought Peace but Found War. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 2004) and Stan Hoig, The Peace Chiefs of the Cheyennes (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980).

4. See Laura F. Klein and Lillian A. Ackerman, eds. Women and Power in Native North America. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005).

5. Anthropologists argue that the Cheyenne were matrilocal and matrilineal but not matriarchal. The distinction is made in this paper since many community members who participated in the conference, "Journey from Darlington," were confused by these distinctions. Basically, a people can trace their lineage through the female line and live with their mothers and still not be considered matriarchal. Matriarchy implies female control of political and cultural life and tribal decision making.

6. George Bird Grinnell along with George Hyde set the tone for much of the early scholarship on Cheyennes. The emphasis on the Cheyenne warrior culture could in part be derived from recent scholarship that suggests that a third George, George Bent, provided both George Bird Grinnell and George Hyde with the bulk of their sources in the form of letters. Bent was the son of William Bent and Owl Woman, a Cheyenne daughter of an Arrow Keeper and therefore from a prominent Cheyenne family. George Bent wrote over 2,000 letters to the two other Georges, many of which were quoted at length but not attributed to him. He spent part of his youth fighting the U.S. Army as a Cheyenne warrior. See Lincoln F. Faller, "Making Medicine against 'White Man's Side of the Story': George Bent's Letters to George Hyde." American Indian Quarterly.24:1 (Winter, 2000): 64-90.

More recent scholarship has included peace themes. See Thom Hatch, Black Kettle, and Stan Hoig, Peace Chiefs. Also see, John H. Moore, Cheyenne Nation, for a treatment how peaceful "uterine" factions gave way to the warrior "agnatic" dog societies of the Cheyenne nation.

7. Mike Cowdry. Arrow's Elk Society Ledger: A Southern Cheyenne Record of the 1870s. (Santa Fe: NM: Morning Star Gallery, 1999).

8. Charles King, Campaigning with Crook (New York: Harper & Brothers. Reprint edition, 1964. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), 33; as cited in Mike Cowdry. Arrow's Elk Society Ledger, front material.

9. For scholarship on Native American women that includes gender, anthropology and history see Klein and Ackerman; Patricia Albers & Beatrice Medicine, eds., The Hidden Half: Studies of Plains Indian Women. (New York: University Press of America, 1983); and Beverly Gretchen M. Bataille and Kathleen Mullen Sands, American Indian Women: Telling their Lives. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1984). For a comprehensive bibliography through 1983 see Rayna Green, Native American Women: A Contextual Bibliography. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983). For additional scholarship that does not include gender theory but contains helpful descriptive and narrative passages see Beverly Hungry Wolf, The Ways of My Grandmothers. (New York: Quill, 1982); Bertha Little Coyote and Virginia Giglio, Leaving Everything Behind: The Songs and Memories of a Cheyenne Woman. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994); and Virginia Giglio, Southern Cheyenne Women's Songs. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994).

10. See the introduction to Klein and Ackerman, Women and Power.

11. Grinnell as quoted in Hoig, 24.

12. Hoig, 14.

13. Frederic Remington, On the Apache Indian Reservation and Artist Wanderings Among the Cheyennes. (Palmer Lake, CO: The Filter Press, reprint 1974), 22.

14. For a description of women's clothing see Cowdry, p. 75. Virginia Bergman Peters includes an interesting description of cosmetics used by Plains women. See Women of Earth Lodges: Tribal Life on the Plains (North Haven, CT.: Archon Books, 1995), 82.

15. See Virginia Giglio who writes in Southern Cheyenne Women's Songs, 11, "Historically, Cheyenne women were noted for their dignity and chastity, and wielded strong moral influence within the tribe."

16. Col. Richard Irving Dodge, Our Wild Indians: Thirty-three Years'Personal Experience Among the Red Men of the Great West (Hartford, CT: A.D. Worthington & Co., 1882), 345.

17. Ledger art found in Cowdry's book and oral traditions describe courting patterns. See Cowdry, Arrow's Elk Society Ledger, and Interview with Lawrence and Betty Hart, May 2005, Clinton, Oklahoma.

18. George Bird Grinell, "Cheyenne Woman Customs," American Anthropologist, New Series, 4:1 (Jan-Mar, 1902).

19. An 1880 census may help to clarify birthrates.

20. See George Bird Grinnel, "Cheyenne Woman Customs, 15,

21. Richard Irving Dodge, Our Wild Indians, 205.

22. Nancy Lurie as quoted in Carolyn Niethammer, Daughters of the Earth: The Lives and Legends of American Indian Women. (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1977): xiii.

23. Bertha K. Petter, Two Life Sketches of Vxzeta and Vohokass (Lame Deer, Mont.: Petter, 1936?), 57.

24. Rodolphe Petter, Reminiscences of Past Years in my Mission Service among the Cheyenne (Lame Deer, Mont.: Petter, 1936?), 15.

25. Interview with Lawrence Hart, May 2005, Clinton, OK.

26. Virginia Bergman Peters, Women of Earth Lodges: Tribal Life on the Plains (North Haven, CT.: Archon Books, 1995).

27. The scholar in search of Cheyenne-specific material culture and sources will be easily frustrated as native tribes are often grouped together by region and cultural similarity. An Eastern Mennonite University colleague, anthropologist Douglas Hertzler, explained that anthropologists study tribal groups in relation to one another and tend not to single out specific tribes.

28. Moore writes: "Because of trade, by 1850 the Cheyennes had transformed themselves from a marginal horticultural tribe of Middle Missouri to a very successful nation of hunters and traders. And it is here that we can ask a significant historical question: How did it happen that the Cheyennes were the only one of the Middle Missouri horticultural tribes that succeeded in making the transition to equestrian nomadism in this period? That is, we should ask not only why the Cheyennes were successful, but also why the Arikaras, Mandans, Hidatsas, and Pawnees remained immobilized on the Missouri, frozen in space, while their cultures and populations were destroyed by wars and disease between 1800 and 1860" (p. 139).

29. Lincoln B. Faller, "Making Medicine against 'White Man's Side of Story': George Bent's Letters to George Hyde." American Indian Quarterly, 24:1 (Winter, 2000): 71.

30. See Moore's account of Cheyenne farming, pp.68-73.

31. Peters, p. 4.

32. Elliott Coues, ed. New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry and David Thompson, 2 vols. (Reprint edition 1965; Minneapolis: Ross & Haines), I: 360.

33. Cowdry, p. 48.

34. James Mooney, 1903, as referenced in Moore, "The Developmental Cycle of Cheyenne Polygyny," American Indian Quarterly, 15:3 (Summer, 1991): 312.

35. Cowdry, p. 47.

36. Mary Jan Schneider, "Women's Work: An Examination of Women's Roles in Plains Indian Arts and Crafts" in Patricia Albers and Beatrice Medicine, eds. The Hidden Half: Studies of Plains Indian Women (New York: University Press of America, 1983): 110.

37. Royal B. Hassrick, The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964).

38. Winfield Colman, Art as Cosmology: Cheyenne Women's Rawhide Painting. Internet source: http:www.tribalarts.com/feature/Cheyenne/index.html.

39. Rodolphe Petter. Historical Sketch of The Northern Cheyenne Mission Field, MLA-MS-31-13:120, no date available.

40. Schneider, p. 109.

41. George Grinnell, The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Ways of Life, 2 vols. (Hew Haven, Yale University Press, rpt. 1972, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.), I: 147-48; II: 389.

42. Moore, p. 138. See also Moore, "The Developmental Cycle of Cheyenne Polygyny," American Indian Quarterly. 15:3 (Summer, 1991): 311-328.

43. Moore discusses the difficulty of tracing family genealogies in his 1991article. With more than one wife in the tipi and a census enumerator unfamiliar with Cheyenne polygyny, descent lines were ambiguous at best. See p. 320.

44. See Moore, Chapter Five, "The Central Plains Environment."

45. Moore, Cheyenne Nation, 196.

46. Moore, Cheyenne Nation, 196, 254, 274.

47. Clyde Ellis, "The Christian Faith and Indian Cultural Survival," presented at the "Journey to Darlington" conference.

48. Petter, Reminiscences, 23.

49. Petter diary, MLA-MS-31, 1:5.

50. Sharon Klingelsmith. "Women in the Mennonite Church, 1880-1930," Mennonite Quarterly Review (July 1980); Ruth Unrau, Encircled: Stories of Mennonite Women (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1986), Mary Lou Cummings, Full Circle: Stories of Mennonite Women (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1978).

51. The Cheyenne and Arapahoe Messenger, vol. 3 (March 1930): 4.

52. Star Mission Club minutes book, opening page. The book is in the collections of the Cheyenne Cultural Center, Clinton, Oklahoma.

53. Star Mission Club minutes book, September 20, 1939.

54. Klingelsmith, "Women in the Mennonite Church."

55. Email from Lawrence Hart to Kimberly D. Schmidt, March 8, 2006.

56. Star Mission Club minutes book, September 20, 1939.

57. Star Mission Club minutes book, November 16, 1939.

58. Charles E. Shell, "Report of the Superintendent in Charge of Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency, Darlington, Oklahoma, August 20th, 1907," Report Concerning Indians in Oklahoma, Oregon and Pennsylvania, Comprising annual reports, for year ending June 30, 1907.

59. G.A Linscheid, The Cheyenne and Arapahoe Messenger, 8:5 (May 1937), 3

60. Missionary News and Notes, vol. VIII, No. 2, (October 1933), 1-2.

61. Interview with Lenora Hart Holliman, March 8, 2005, Clinton, OK.

62. Interview with Betty and Lawrence Hart, May, 2005, Clinton, OK.

63. Interview with Connie Hart Yellowman. May 8, 2005, Clinton, OK.

64. Interview with Margie Pewo, May 9, 2005, Hammon OK. Betty Hart mentioned during her interview that her son-in-law, Gordon Yellowman, was also respectful of her and used to leave the room when she entered for a time after Gordon and Connie were married.

65. Margie Pewo interview.