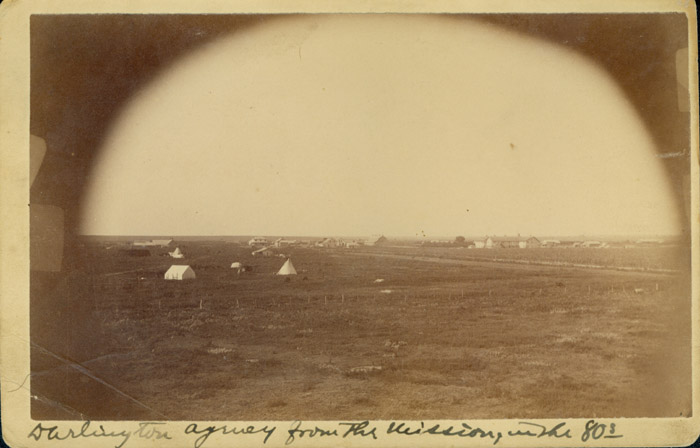

Darlington agency seen from the Mennonite mission, ca. 1885

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

Barbara A. Thiesen is co-director of libraries at Bethel College.

Darlington agency seen from the Mennonite mission, ca. 1885

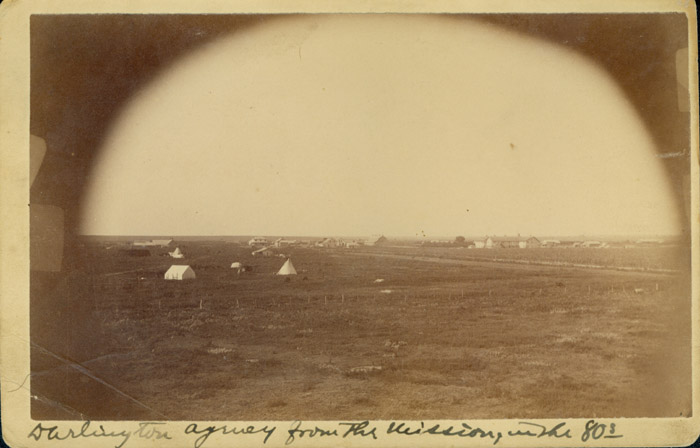

The background and development of the missionary interests of the Mennonites that led up to the first mission at Darlington have been described elsewhere.(1) To distill that development down to just a few words: In 1872 at the sixth session of the General Conference, the Foreign [in German Heiden, literally "Heathen"] Mission Board was formed. In 1875 at the seventh session of the General Conference, Samuel S. Haury was accepted as missionary. However it wasn't until May1880 that Haury and his bride, Susie L. Hirschler (married in November 1879), arrived in Darlington to begin the first "foreign" mission of the General Conference of the Mennonites of North America. Little seems to have been written about the mission work at Darlington which was primarily among the Arapaho—the first seed of Mennonite missions. Much of the focus in the past has been on the mission work among the Cheyenne, which began in 1883 at Cantonment.

John D. Miles

The Haurys' arrival in Darlington came after several years of seeking a mission field, but more immediately at the express invitation of John D. Miles, the Quaker Indian agent at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency at Darlington, Indian Territory. In a letter dated 10 December 1879, translated to German and published in the February 1880 Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt, Miles wrote, "I hardly know of a better field for a missionary than this Agency." He indicated that the Quaker missionaries had temporarily left the field, but on their return would focus on the Cheyenne. He concluded his letter with the following invitation: "I can say here that the doors to the Arapaho are wide open for you and your church, and we bid you welcome with great joy if you are coming soon."(2)

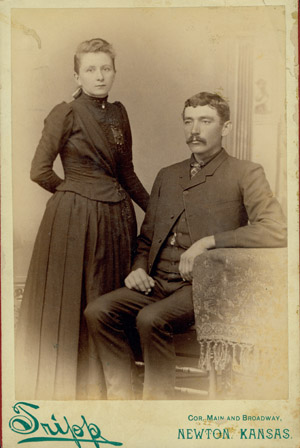

Susanna Hirschler Haury and Samuel S. Haury

But the beginning was hard, as Haury wrote in a letter dated 15 Juli 1880—"Aller Anfang ist schwer."(3) On the trip to Indian Territory, Susie Haury suffered from an attack of "bilious fever" that lasted two days. Shortly after their arrival S. S. Haury suffered from a bout of diarrhea and fever which prevented him from preparing their house for moving in.

Upon their arrival at Darlington, the Haurys lived with Agent Miles and his wife while a small house was cleaned and prepared for them. Once they were able to move into the house, Haury went about making furniture from boxes, and they slept on the ground since their belongings had not yet arrived. In a very short time the Haurys had a garden and negotiated with a neighbor to get milk. While these things seemed to be going well, Haury was not, as he said, having good luck with the horses. One suffered a wound in the neck and the other was lame for eight days.(4)

With all the manual labor that needed to be done, Haury had not yet had time to do mission work. In a letter that appeared in the July 1880 Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt, he wrote,

How we will work, I do not yet know. Probably most weekday evenings I will instruct the children in the school in the Christian teachings in the English language and probably will cover Biblical history. The Sunday school on Sunday mornings will be continued as usual and my wife and I will be involved in that. Sunday afternoons we will probably visit the Indians in their camps now and then and will arrange meetings, which I intend to lead alternating with the Quaker missionary — one time the same will take place near the Arapaho and then near the Cheyenne. One must speak through interpreters, which I don't do gladly, but at the present time what else can one do? The Sunday evenings we'll have a service in English for the whites, which I promised to likewise lead alternately with the Quaker missionary. - Concerning the acquisition of the language, I do not yet know how we will proceed. Our intention is to take into our house one or two Arapaho girls that already understand some English, in order to get a hold on the language in this way.(5)

While the Haurys were not directly engaging in what they thought of as "mission work," the Indians were visiting the Haurys and receiving meals from them, often as many as six Indians a day. Powder Face and Cut Finger, two Arapaho chiefs, made frequent visits and since the two understood some English, Haury used their visits as an opportunity to learn some Arapaho words.

Government school for Arapahos at Darlington, ca. 1890

The main intent of the missionaries was to work with the Arapaho children (initially those in the government school) and through them bring the adults to Christianity. The Haurys' arrival in late May, not long before the end of the school year, made that beginning difficult because at the end of June the children returned home to their parents for a two-month break. Thus that avenue was closed until the new school year. And while during those few weeks before school closed, Haury occasionally led a Sunday school in English for the children, for the adults he needed an interpreter.

Government school for Cheyennes at Darlington, ca. 1890

The camp meetings which Haury had begun with the adults also were discontinued for the summer, for which Haury was partly glad since he did not find preaching through an interpreter who "does not have a sense for the truth and whose life stands in contradiction with the same, often does more harm than good." At the same time, however, he noted that there were usually between 50 and 100 Indians present.(6)

Additional work included a regular Sunday evening service with the whites, which Haury and the Quaker missionary took turns leading. During the summer a Sunday school was organized for the whites, although Haury sought to get the Indians to come, an endeavor that was frustrated by not understanding the Arapaho language, and thus described by Haury as "fruitless."(7)

It didn't take long for Haury to see the necessity of putting all his energy into learning the language, although it seemed that there were "so many small things, which nevertheless must also be done, which keep one from the language study."(8) But a new mission helper, Cornelius F. Duerksen, was to arrive soon (September 1880) and then Haury hoped to spend more time among the Indians.

At the beginning of September, the children began to return to school. Much of the religious work that had gone on in the summer continued in the fall. Haury keenly felt the need to spend more time learning the Arapaho language and asked to be released entirely from preaching to the whites. He found that with the children understanding so little of what he said, there was little profit in the time he spent with them. Furthermore, trying to teach the children in the evenings when they were tired from the school day was a further hindrance.(9)

To illustrate his point with the difficulties of the language, Haury gave an example that appeared in the November 1880 issue of the Nachrichten. "In order to express the word 'God', they have the word Tschaba Nihaathu (Tschaba = above; Nihaathu = white man) 'the white man above.' The expression is decidedly wrong, as the Indian sees in the white man only his blackmailer and oppressor."(10) Haury went on to lament that if he could determine what the Arapaho word for "Great Spirit" was, that would be much more suitable, but for reasons unknown to him, the Arapaho were "very uncommunicative" about what that word would be.

By the end of 1880, after about six months in the field, conditions had not greatly improved. Haury wrote in his quarterly report at the end of the year,

Some dear mission friends at home may already expect reports of shining successes and striking fruits of our labor. Those who think this completely forget, however, that it is first necessary to root out and remove the hedges, before one can plow, only then can one sow. We cannot yet sow, let alone reap. Also the conditions are not at all the way others paint them, as if the people listened and accepted the Word with joy … and as if we could teach the children in the Arapaho school, which is established, supported and guided by the government, completely according to our own view and opinion of Christianity.(11)

Haury explained that a new superintendent was now in charge of the government school, a change he did not see as positive, for with this superintendent's arrival the missionaries were no longer permitted to hold Sunday school classes in private homes. Susie Haury had been teaching a class of six girls at home because she was unable to get out (possibly because of pregnancy), but with this change Haury had to take over her class. In his report, Haury declared that the more independent from the government the mission efforts could become, the better.

In the fall of 1881, more than a year after the missionaries arrived, it finally seemed that the focus could shift to "mission work." The mission building was complete with "kitchen and dining-room in the basement, a school-room and three private rooms on the first, five rooms on the second floor, and two dormitories in the garret."(12) The missionaries could begin holding school in their own building; they were no longer under the direct supervision of the government. By August they already had children requesting admission to the school and soon thirteen students were accepted. They received additional applications, but had to turn them down because they did not have enough clothing for more children and because the Government school had to be filled first.(13)

In Haury's 1881 annual report to John D. Miles, the Agent at the Darlington Agency, he indicated that the Mennonites intended to "teach the children in school the common elementary branches in the English language, and in connection with it we shall instruct the boys in farming and the girls in housekeeping and common needlework. But one of our main objects, in school work even, will be the teaching of Biblical and Christian knowledge and the inculcation of Christian principles."(14)

Then in February of 1882 on the night of the 19th, a very cold and stormy night, the mission building burned down. Four little children, including the Haurys' 9-month old son, Carl, and three half Indian, half white children (Jenny, Walter, and Emil) that the Haurys had taken into their home, died in the fire. The Haurys lost everything. In a special report published by the Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt Haury wrote, "What my heart felt with a look at these 4 little corpses and everything that was connected, I am not able to say. One must be led in such depths of sorrow and pain in order to grasp it."(15)

The fire did not end the vision of the missionaries and the Mission Board. In the same special issue of the Nachrichten in which the fire was announced, Christian Krehbiel described how the school was continuing in tents provided by the commander at Fort Reno and proposed that a new building made from bricks should be constructed. In the next several issues of the Christlicher Bundes-Bote (which had absorbed the Nachrichten) the Mission Board proceeded to ask for donations for this rebuilding project.

By December of 1882 the new brick mission building was completed — $5000 of the $7000 appropriated by Congress, the remaining $2000 from Mennonite donations(16) — and the mission school opened again. Haury wrote in his annual report to Agent Miles that since the school was not ready in September there were not as many children enrolled as could have been accommodated. About 25 children were in regular attendance and were being taught as before: the English language, industrial education, and Christian religion. As in previous communications, Haury repeated his belief that if you

show me an Indian who has accepted Christ as his personal Saviour to a change of heart, and I will show you a civilized Indian with a radical change of life. We may teach the Indian child all the arts of our civilized life, keeping him away from the influence of his ignorant, superstitious, and idolatrous tribe for many years, but without a living Christ in the heart such a child, returning as a young man to his people, will soon fall back into the old superstitious customs and habits of his race. The Indians are a religious people; religion penetrates their daily life; almost every act that they do is connected with some religious meaning, scrupulously inculcated into the child from its infancy; and they will be civilized only by giving them a higher, the only true religion, that of Christ. We see this verified by the movements of some of the adult and aged Indians, and especially by their tribal connections, customs, and habits. Seeing this, they more than ever begin to oppose educational and missionary work. Seeing the value of Christian religion, quite a number of our boys and girls are earnestly seeking the truth, and this has a powerful influence on themselves respecting their daily life and conduct in school, and in camp upon their own people.(17)

John Miles, the Agent at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency, remained very supportive of the Mennonite mission. In a report in the 1 October 1882 Christlicher Bundes-Bote, Carl J. van der Smissen, Secretary of the Mission Board, wrote about the Agent's ongoing support and that one of the ways in which this support was expressed was through hiring Mennonites to work in the government school, D. B. Hirschler as superintendent, A. [Anna?] Haury as housemother, and Elizabeth Welty as assistant matron.(18)

At the same time the Darlington mission building was being rebuilt, Haury reported to the Mission Board that abandoned military barracks at Cantonment were available for the Mennonites to expand their mission (and perhaps prevent other denominations from encroaching on the "Mennonite" field). The Mission Board decided to take up the offer and H. R. Voth was sent to "guard the barracks till arrangements could be made to occupy same."(19)

Annual reports to the Agent indicated that the mission work continued on despite the obstacles. Haury wrote in his 1882 report, "As to the prospects and hopes of our work I can say we are not in the least discouraged. Though this work is one of very slow progress, we have been privileged to see so much in the past that it is a work which pays richly in the end. We can therefore take courage and go on with it cheerfully and earnestly."(20) The conclusion of his 1883 report was in a similar vein, "We are … not at all discouraged, but will continue in this work with good courage and hope if God spares our lives, knowing that the Gospel of Christ will at last conquer the hearts of our Indians and change their lives and customs; it will civilize them"(21) [emphasis Haury's].

During these early years, the Haurys were not the only mission workers at Darlington. In the first five years of the mission there were at least twenty employees in addition to the Haurys including:

Most of these workers remained for only one to three years. Articles in the Nachrichten indicate there were others who came for only a few months.

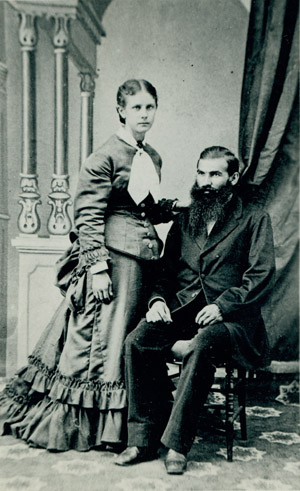

H. R. Voth and Barbara Baer Voth, 1884

H. R. Voth arrived in Darlington in June of 1882. The following February he began an evening school with the Indian employees of the agency. They met three times a week, with Voth communicating primarily by sign language. At first the students, about 10 of them between the ages of 25 and 45, were quite industrious and better behaved than "some white people under similar conditions,"(23) but Voth was concerned that once the weather turned nice and the daylight lasted longer, that attendance would drop off. This proved to be the case and in his second quarter report for 1883 he noted that after consulting with the Agent, the school was closed on the 4th of May, but the Agent suggested that Voth consider starting it up again in the fall.

1883 also saw the Haurys move to Cantonment and Albert E. Funk placed in charge at Darlington. The following year Funk transferred to Cantonment and H. R. Voth became the superintendent at Darlington.

So barely three years after its founding, Darlington was no longer the only mission of the Mennonites and thus no longer the main focus of all mission reports in the various Mennonite publications. In fact, the third quarter report for 1883 declared Cantonment to be the "main station" and the place where "our mission can develop freely, the mission can there be completely operated in the Mennonite Christian sense."(24)

Darlington Mennonite school building; on the veranda, left to right,

Susie Richert (married C. H. Wedel), Maria Lehrman, Barbara Baer Voth

and daughter Frieda; foreground, H. R. Voth with Indian children, ca. 1884

Indian agent Daniel B. Dyer and his wife, with Indian police,

at Dyers' house, 1884

1884 brought the departure of John Miles, who had been agent at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency for twelve years. He was replaced by Daniel B. Dyer, who had been the agent at the Quapaw Agency (in northeastern Indian Territory).(25) A reading of his annual reports to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs indicates a much harsher attitude toward the Indians than Miles had exhibited. Dyer complained about the lack of power to "control" the Indians and the necessity of making them "conform to the will of the Government or take the consequences" and called for swift punishment for wrongdoing.(26) Dyer also didn't have much good to say about the Government schools, claiming they were "certainly little credit to teachers, Indians, or any one else connected with the work." However he followed up those comments with praise for the Mennonites, saying, "What I have said of the Government schools proper will not apply to the two schools controlled by the Mennonite Society. Their schools, although having a small number of pupils, have been quite successful." According to his report, the average attendance at the Cheyenne Indian boarding school was 71; at the Arapaho Indian boarding school was 66; Mennonite mission at Darlington agency was 28; and Mennonite mission at Cantonment was 22.(27)

Second Darlington mission school, built in 1882; H. R. Voth on porch,

ca. 1885

Dyer again expressed his positive opinion of the Mennonites in his 1885 annual report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in which he wrote,

It is no small compliment to the devoted, charitable, and benevolent Mennonites to say that they are the most earnest workers I ever saw engaged in the missionary work. Rev. S. S. Haury, Mr. H. R. Voth, and their faithful colaborers deserve more credit than all the words I can write will express. Their work is a life one, to better the condition of the poor people, and their services in this direction are exceedingly valuable. The best plan for civilizing Indians is a serious question, and the facilities for making them either intelligent or useful members of society are poor and imperfectly developed, but these missionaries teach them to work, which in my judgment is the most valuable lesson they can learn. They deal honestly with the Indians, and think that the Indians should be made to deal fairly and honestly with the whites, respect their rights of property, and be punished for any crimes they commit.(28)

Stereoview of Darlington mission school, 1885;

H. R. Voth with children in foreground,

women mission workers on balcony

The mission work continued on for the next several years as it had in the first five. The quarterly reports indicated much sickness among the Indians, frequent loss of interpreters (usually young people who had gone to Carlisle, the Indian industrial school in Pennsylvania, and, after a brief time back in Indian Territory, returned to "camp" life and were no longer interested in either interpreting, teaching the language to the missionaries, or further Christianization). In his 1885 report to Agent Dyer, Haury noted,

It is self-evident that as a Christian missionary enterprise we should, above all things, impart to these people instructions in the Christian religion, to bring them to the understanding of the vanity of their customs and ways, and to point and lead them to the only true and living God, the author of all true happiness and genuine civilization. The meetings which we held Sabbath after Sabbath to accomplish this were fairly attended by camp Indians all the year; and although we have not the gratification of reporting personal conversions from heathenism to Christianity, we can see a marked advancement in the daily walk and life of those who had the benefit of hearing God's word, and being more or less under our training and teaching by word and example.(29)

Darlington mission school: main building, wash house, barn-shed, corrals.

Taken fron the south, ca. 1886

Could a connection be made between the lack of conversions and the focus of the mission activity being primarily on children who often became sick and died before being of an age to be baptized according to Mennonite doctrines? For example Josiah Kelly was at the Halstead school(30) for two years and upon his return did some interpreting for H. R. Voth. Josiah received an offer from the government's carpentry shop for a position that would allow him to earn money while learning the trade. He left the mission to do so, although Voth allowed him to continue getting room and board at the mission as long as he attended evening devotions, the prayer-meetings, Sunday school, and would let Voth know if he wished to go out after evening devotions. Eventually Josiah decided those terms were too strict and he left, although he continued to visit occasionally. Some months later, by which time he was "emaciated and weak," Josiah requested he be allowed to return to the mission. He remained at the mission for about two weeks and then requested permission to return to his aunt's, where he spent his last days dying from consumption. Voth visited him frequently and almost daily sent food for him to eat. Josiah became more interested in matters "concerning the salvation of his soul" and on his deathbed "expressed the desire to be prayed for. After some questions with regard to his faith for the future, he confessed an earnest belief that his soul would be saved, after which he died." Voth added that he "felt the seriousness of the moment when the hand of God again plucked fruit from our mission tree. Was this fruit ripe? I could not otherwise but in fervent prayer commit this soul into the grace and mercy of God. I cannot but believe that Josiah in the eleventh hour has found grace and pardon."(31)

Darlington school children and teachers, 1886. "x" marks Maggie Leonard.

Teachers left to right, Susie Richert, Dian Luginbuehl, Barbara Baer Voth

and daughter Frieda, Maria Lehrman, H. R. Voth in doorway.

Lower left standing, Abe Nace. Seated center front, J. H. Schmidt.

Darlington school children and teachers, 1886 or 1887.

The Mennonite Library and Archives has another copy of this photo

which gives the names of almost all of the children.

Finally in June of 1888 came the exciting news that the Mennonite mission had baptized its first convert. A. B. Shelly's description of this joyfully welcomed event was reported in the September 1888 issue of The Mennonite:

Sunday was a most interesting and gladsome day for us all. It was the day set apart for the baptism of one of our mission children at Darlington, a young girl 17 years old [Maggie Leonard], who had some time before made application to be baptized and admitted in the church of our Master. This being the first baptism at our mission it made the occasion the more solemn and interesting.(32)

Maggie Leonard

Shelly went on to say that the mission efforts had

not been in vain. A decided difference has been produced by our missionary labors. And the word of God, which is daily taught in our schools, is working like a leaven and will finally bear its rich fruit. It is not only the children that are brought under the influence of the truth of the Gospel. Marked impressions are already made upon some of the parents of these children and although our missionaries are not yet able to speak to the Indians in their native tongue, which no doubt is a great hindrance in the work, yet they can speak to them through interpreters, besides which many things are told them by their children of what they have learned in school. I cannot otherwise but believe, the time is coming, and it may be nearer than we think, when these Indians, whom the Lord has entrusted to our care, will earnestly and sincerely ask the question, 'What must we do to be saved?' For the speedy coming of this time let us earnestly work and pray.(33)

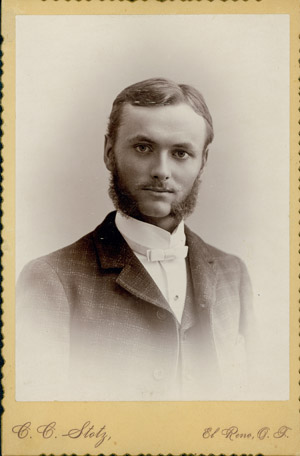

Andrew Bauer Shelly, ca. 1910

By 1888 the government policy of relocating the Arapaho to individual farms(34) began to have a noticeable effect on the mission work. In his third quarter report for that year, H. R. Voth noted,

Whether it will be possible for me to hold regular Sunday services with the Indians here during the winter is doubtful, unless I can find a capable interpreter. There are not many Arapahoes living near here. If they do not come here, I will as much as I can, and the Lord give me grace for it, go to them, seek them in their camps and forests, and bring them the simplest truths of the blessed Gospel. It is uncommonly hard to induce the Indians to come for it for themselves.(35)

It is difficult to determine what the missionaries really thought about government policies and their effect on both the Indians and the mission work. However, beginning in the late 1880s and into the 1890s, the missionaries' reports included more than just an accounting of the work with the Arapaho and Cheyenne. Voth's 1888 fourth quarter report quite bluntly addresses what he views to be the problem at that point: the ration system. He argued that the government should give up the system and give the Indians

their own land, supply them with farming implements, etc., and place over them capable farm superintendents, and then say to the able-bodied now, 'swim or sink!' Surely I am far from the belief that the salvation of these poor people depends upon any particular Indian policy of the government. I know full well that their true salvation flows not from Washington but from Calvary, and not through this application of congressional and Indian official enactments, but through the preaching of the Gospel, can the great and difficult Indian problem be solved. But the process of renovation of these people can be alleviated and promoted, or impeded and aggravated by the laws of the government. We do manual labor, first, because we know the good effect of it, and second, because we must work to live. To the Indian the worth and blessing of work is unknown, and to work for a living is unnecessary under the present system.(36)

Again in 1889 Voth addressed policy issues in his first quarter report to the Mission Board in which he expressed concern about the possible effects of immigration on the mission as a result of the opening of the reservation to settlers since the western limit of the reservation was only two miles east of Darlington. In the same report, Voth explained why he thought that more of the Indian young people who had been to eastern schools did not attend the worship services at the mission. In a conversation with one young man who was boarding at the mission, Voth was told that if there were a church organization, the young man would join. Voth responded that the mission was "a small congregation." He went on to express the concern that the young people who had spent time in the eastern schools had "become accustomed to attend church and school. They come back and here find, according to their views, no churches and church organizations, only schools." Worship services in the mission school didn't seem to be church, in the eyes of these young people. As a result, Voth wrote, "after a long quiet deliberation [I have] come to see in this the chief reason that so few of the young people attend our worship. I have reason to believe, that if we would erect a small church, we would have larger audiences and could probably soon gather a small congregation. I verily believe that if another denomination should start a mission here it would soon build a church." He then proceeded to ask whether it would be possible to erect a church at the Darlington mission.(37)

During the second quarter of 1889, Voth made a trip to Kansas for mission and baptismal services. He was gone only a few weeks, but commented on how much things had changed in Oklahoma by the time he returned. His biggest concern was the proximity of new towns to the mission station and he feared that the Indians would be exposed to bad influences. He greatly hoped that a number of Mennonites would settle in the area as they would be a "greater advantage and blessing for the Indians and our mission work … instead of a mixed frontier element."(38)

Voth continued to comment on the need for a church at Darlington and, in fact, $40 was received by the Mission Board for erection of a church. However, the Board was not prepared to undertake such a project at that time since they were in the process of building a new mission building at Cantonment and establishing a new station at Washita.(39)

Voth's annual reports to the agent addressed problems that he believed were the result of the government's Indian policy. He thought the future of the Indians was becoming darker and more hopeless because the government policy was, as he described it, "a self-destroying one. What it builds up to-day it breaks down to-morrow." Christianity was the means to lifting these people out of their darkness, not the political machinery of government.(40) In his 1889 report, Voth took the government to task for not "compelling" the Indians to turn over a new leaf, specifically as it related to the issue of marriage. The Indians should be forced to marry according to the laws of the land, not according to their traditions.

At the same time, he again wrote in favor of forcing the Indians onto individual farms as a way to force Indians to help themselves and in 1889 repeated his arguments that rations should be discontinued and the Indians who want to farm should be given the necessary land and equipment. Additionally he argued that, "The non-progressive Indians should not be allowed to camp near such families or settlements at all, neither should any heathenish customs and practices be allowed in them. And every newcomer from the Eastern schools should be provided for in the same manner, instead of giving a ration ticket to him and then turning him loose into the camp with all it dangers and pernicious influences."(41)

ca. 1890; "west of Darlington mission school

on the morning when Indian children were to leave

for Halstead, Kansas, to go to school at Christian Krehbiel's";

front row left to right, David? Todd, Frieda E. Voth,

H. R. Voth, Mary Todd;

back row left to right, ? Trempe, John Pedro,

Della Haury, Mollie ?

ca. 1890, missionaries at Darlington, Oklahoma; left to right, Martha Moser (later married H. R. Voth),

Maria Suderman (married William Bartel), Jacob H. Richert, J. H. Schmidt, H. R. Voth, Frieda E. Voth,

Abe Suderman (died 1891), Anna Voth (married J. H. Schmidt), Anna Penner (married Leonard Bartel)

The following year Voth expressed the hope that the Government efforts to settle the Indians on allotments would be successful and "that with the breaking up of the tribal relation of these Indians a great many of their old customs will be discontinued."(42) This complaint came in response to a return by the Arapaho to their medicine dances which had been on the decrease, at least according to Agent G. D. Williams' 1887 report in which he claimed, "The sun dance is fast becoming an obsolete ceremony. The one held this season was a tame affair, and indulged in by but a few of the Cheyennes, the Arapahoes having held none for two years," a change to which he credited "scattering the Indians by location on separate farms, thus giving them individual responsibilities, also to the breaking up of the 'dog-soldier' element which formerly compelled the attendance of every Indian."(43) But in the winter of 1890-1891, the Ghost Dance movement had spread to the Arapaho in Indian Territory and the result for the Mennonite missionaries was fewer children in attendance at their schools. Whereas the Darlington school had been running at or near capacity with between 45-50 students, in the fall of 1890, there were only thirty-five. J. H. Schmidt, teacher at Darlington, wrote in his quarterly report that "all efforts to procure more children proved futile…. The many dances and the well known Messiah revels among the Indians are a great hindrance to the mission work in our schools here."(44)

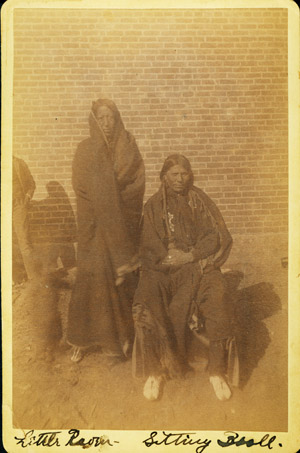

left, Little Raven; right, Sitting Bull, ca. 1890

Voth had a chance meeting with Sitting Bull, who promised to encourage the Indians to attend meetings with the missionaries in order to become "acquainted with the teachings of the Bible."(45) In spite of Sitting Bull's promises, the summer of 1891 was a restless one for the Indians and thus a time of frustration for the missionaries. Voth wrote in his quarterly report that the Indians were to receive payment for their land, but the money arrived several weeks late so that the Indians became restless and dissatisfied. Mission work seemed fruitless. It was impossible to gather the Indians together for worship services. Voth went into the camps and spoke with individuals, "reminding them of their immortal souls and trying to point them to the Lord," but he was unsure of whether the seed he was sowing was falling on rocky or fertile ground.(46)

ca. 1891, Darlington Indian agency. The large building was the government school for

Arapaho children. H. R. Voth in the foreground, with Indian children picking flowers.

The situation persisted in this fashion into the fall. When it was time for school to open in the fall of 1891, the agent met with the chiefs who told him that they were focused on the allotments and on settling on land and could not think about the schools. According to Voth even Left Hand, who had always been a strong supporter of the schools, was of the same opinion. The agent threatened to withhold rations, but they persisted in their attitude. Thus, according to Voth, "the consequence is that it never before held so hard to obtain children for our schools as is the case this year."(47)

Left Hand

Increasingly the changes in government policy were beginning to affect the mission. In the 1889 Annual Report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the Commissioner, T. J. Morgan, wrote about the need to put things into "more systematic and organic form,"(48) although he still saw the "urgent need of consecrated missionary work and liberal expenditure of money on the part of individuals and religious organizations" but this work and money would be supplemental to the Government.(49) In his 1891 third quarter report, Voth noted that much more effort and money was being placed into the government schools than had been previously. The Arapaho government school was to be improved and a large government school erected within the Seger Colony.(50) Voth feared that "After all these schools are finished it may be right hard for us to obtain children for our humble Mission-schools. However, then the time may have come for us to at least discontinue our Boardingschool here at Darlington and devote more time and attention to missionwork among adult Indians."(51) T. J. Morgan's 1891 annual report would seem to bolster Voth's fears. In it Morgan spoke in favor of nonreservation training schools for the "most useful all-around practical education"(52) and he wrote about contract schools, which the Mennonite schools were, saying that "the policy of aiding church schools is one that has grown up as a matter of administration, having only a semblance of legislative authority. But the rapid development of the public-school system has brought the Government schools into a position where it is entirely feasible for them at an early day to assume the whole charge of Indian education, so far as it is carried on by the Government." He went on to say, "I believe that the Government ought to assume, absolutely and completely, the control of Indian education, and that these wards should be trained in the Government institutions with the specific end of fitting them for American citizenship, and that no moneys from the public Treasury should be devoted to sectarian or church institutions." He argued that if the churches wanted to have missionary schools, missionary funds, not government funds, should be used for their support. He concluded that it was time to do away with the "mixed system," although the change should be gradual and in the meantime, "the purpose of the office is to maintain practically the status quo, making no changes except such as are rendered necessary by circumstances."(53)

ca. 1890-91, Darlington school children and teachers;

teachers, front row left to right, J. H. Richert, H. R. Voth with daughter Frieda,

Abraham Suderman; back left to right, Martha Moser, Maria Suderman,

John H. Schmidt, Mrs. John H. Schmidt, Anna Penner

Further indication that things would be changing for the mission could be found in the "Rules in Regard to Attendance of Indian Youth at School" passed by Congress in the Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1891 and printed in the 1891 Commissioner's report. Rule II, under the section "Duties of Agents," states, "The prime duty of the agent, in connection with Indian education, shall be that of keeping the Government schools filled."(54)

As noted above, the commissioner was not opposed to the churches doing mission work. "Untold good has already been done much more can be done. … There has never been a better opportunity for the churches to establish schools or missions and prosecute Christian work."(55)

Morgan wasn't able to execute his ideas concerning education of the Indians as rapidly as he had hoped, primarily because Congress did not appropriate all the funds he had requested and secondly because his proposals required a much larger teaching force than had been or was available.(56) However, the Mennonites began to feel the effects of the policy changes by the fall of 1892. Both J. S. Krehbiel, the superintendent, and M. M. Horsch, the teacher at Darlington, complained "of the great difficulty they experience in getting the requisite number of pupils for this school. The chief cause of this difficulty seems to be, that the government schools at Darlington have both been greatly enlarged and that the government officials, as is quite natural, endeavor to have these filled with pupils first. The consequence is, that a portion of our former pupils have been persuaded to attend the government school instead of coming back to our mission school." The school at Cantonment, which was not near a government school, did not experience the same difficulty.(57)

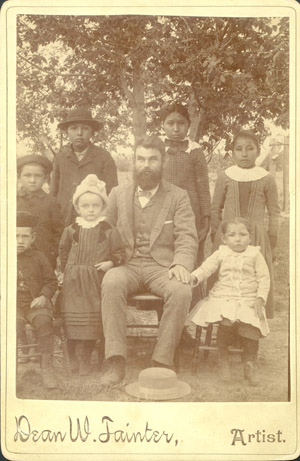

Jacob Samuel Krehbiel (1864-1916) and Katherine Ringelman Krehbiel (1868-1933)

The early 1890s saw major changes in personnel at the mission. H. R. Voth left the Oklahoma mission field in January of 1892. Later that same month, J. S. Krehbiel and his wife, Katie, moved to Darlington, where he took over the mission station as well as the position of acting superintendent of the Mennonite missions. Katie took over the position of matron at Darlington. However, later that year, the Krehbiels moved to their own farm and thus the position of matron became open. Martha Moser, who had been the matron, left the mission field to attend the Fortbildungs-Schule at Halstead with the object, as reported in The Mennonite, "of preparing herself for more real mission-work."(58) In August of 1892 she married H. R. Voth and the following year they went to Arizona to do mission work among the Hopi. John H. Schmidt, who had been teacher at Darlington, left the mission and moved onto his own farm. M. M. Horsch took over the mission school at Darlington.

Michael M. Horsch

These changes came at a critical time for the Darlington mission field. While there had always been change among the supporting workers of the mission, the leadership had remained fairly constant. In the twelve years since the founding of the mission, there had been only two superintendents, first Haury and then Voth, a stability in leadership that was probably crucial in those early years. Now, at a time when government policy was changing and white settlers were moving in and setting up farms and towns around the mission and the Indians were moving around more again, the personnel changes were less than welcome. In his "Annual Report of the Mission Board for 1893," A. B. Shelly noted some of these personnel changes and then commented "This frequent change of workers our board deplores, but it could not be avoided. The longer one is among the Indians, the better he gets acquainted with their nature and their habits and the better he is enabled properly to deal with them."(59)

The Mission Board was also aware of the changes in policy toward the contract schools. As the Indians began to settle down on farms, the necessity of having mission stations scattered where the Indians were located became essential. But, Shelly noted, "As under the new regime the government is providing for the intellectual training of the young Indian; it is not the object of our board to establish schools in connection with these new stations, but to devote our work mainly to the spiritual training of both the young and the old Indians."(60)

When in 1892 the number of pupils for the Darlington school was so small that the school didn't open, the Mission Board considered several options, including: "a) an orphanage; b) a hospital; c) a home for older Indian boys and girls who have returned from school in order to assist them in establishing themselves in civilized, Christian life; d) to take Negro children into the school. The last named plan seemed for a while the most practicable but finally the Government would not consent to the change and so this plan must be abandoned."(61) The idea of converting the school building into a hospital for sick and disabled Indians was carried out only in limited fashion to the extent that a room was arranged and furnished and a man appointed to care for sick Indians.(62)

In 1893 the Darlington school opened again but with only 14 students.(63) The following year, the numbers were almost double, up to an average attendance of 27 students. But the government continued to decrease the amount of money appropriated for schools under private control.

Reports for spring 1894 tell much the same story. Twenty pupils were enrolled, although only fourteen were present. Three of the absent students were ill. Missionary Andrew S. Voth reported "We have hardly any cause to expect much increase in the number of our pupils for the present school year, but for the coming year the prospects seem to be more promising. The Indians are friendly and show a good degree of confidence toward us. Formerly the Arapahoes manifested the greater interest for our school; now this is the case with the Cheyennes. The reason is this, the Arapahoes have but few children at home, nearly all are in the Government Arapahoe School. This school is quite full."(64)

The fall of 1894 saw an increase to about thirty students and the pupils were reported as making "laudable progress in their studies."(65) However at the close of the 1894-1895 school year, the A. S. Voths moved onto their own farm and so the Mission Board was in search of a new teacher. Edward H. Haury came for the new school year and the number of students increased to 39 and remained at about that number the next year as well. In his annual report as secretary of the Mission Board, A. B. Shelly wrote that the mission school at Darlington was "flourishing again, being filled with pupils to its full capacity…. The Indians seem to be much more willing and ready to send their children to our mission schools now than they formerly were, so that there is no lack of pupils for the present. Instead of being obliged to go out and urge them to send their children to school, and in some cases bring the children in by force, as was formerly the case, they now bring them in themselves of their own free will, and thus fill our schools without any special efforts or compulsion on our part. This is one of the testimonies to show that our work done among these Indians has not been entirely without good results."(66)

In the meantime, however, the amount of funds contributed by the government was reduced to zero and the Mission Board was aware that the rations and clothing they received from the government for their pupils would "gradually diminish and ultimately cease. This will necessarily encompass our school work with increased expenses in the future, and it may thus possibly become a cause why this kind of work will have to be reduced to a smaller scale. Even now the sentiment is nourished by some that mission schools should be conducted entirely independent of government aid."(67)

By now, the school was no longer the sole focus of the mission. J. S. Krehbiel and his wife Katie had moved onto their own farm, at the board's authorization, and then back to Darlington for a time. He remained as supervisor of the Oklahoma mission and as superintendent of the Darlington school and continued to devote most of his time to working with adult Indians. Sunday school and evening services were held and arrangements were made with the superintendent of the government school at Darlington to hold religious services at that school every fourth Sunday. However, the other Sundays the religious services were held by other denominations and as reported in The Mennonite, the Mennonites were now going to "be obliged in the future to work by the side of other denominations for the salvation of the Indians."(68)

The year 1897 was another one of staffing upheavals. The Krehbiels returned to their farm at Geary. Edward H. Haury, the teacher at Darlington, was now called to be the superintendent as well, while the position of supervisor was discontinued.(69) His wife Marie (Bergman) was the matron. Haury requested that the Mission Board provide an assistant teacher, but apparently none was found. The following year, 1898, the Haurys resigned their positions and Harvey (H. G.) and Clara Eicher Allebach were hired to fill them.(70) By the time of the Board report published in The Mennonite in June of 1898, however, the circumstances were such that "it seems difficult to continue the mission school in Darlington, and considering that the results attained through the school there seem to be out of proportion with the cost and the work required, the Board believes it its duty towards the congregations to discontinue the school in Darlington." However the Board wasn't quite ready to give up the mission station and decided to search for a missionary to do work with the Indians in the area.(71) Those efforts were unsuccessful and no regular teacher was employed, so the Allebachs were forced to divide the work between them. Allebach described the work thus:

The same children remained under our control as were referred to in the previous report…. As had been done before, we labored among them, seeking to inform and develop their minds toward ends of practical usefulness, and to enlighten their spiritual understanding and elevate their characters by holding before them the promises and precepts of the word of God…. In spite of occasional drawbacks met with in the work, we may believe that the results accomplished during the quarter are not altogether insignificant. We continued to make known to them as plainly as possible the work of God with a view to their conversion, and in the course of our efforts three of our girls were baptized by Bro. J. S. Krehbiel, and admitted to church membership in the Salem congregation near Geary….

In conclusion we may indulge the hope that our attempts to benefit the children though not visibly successful to any extent, may not have completely ended in failure. The word of God prayerfully presented, even to the immature and limited understanding of children nurtured in heathen homes and amidst heathen surroundings, is bound to exert its power upon them in some form or other, at some time or other. But it cannot do its sanctifying work until the hearts of the children are ripe for its reception. We firmly commit ourselves to the belief, that the Spirit chooses his own time, and that contrary to our desires and prayers, He often delays His coming, and thus we may feel well satisfied if we were only instrumental in preparing the way in the children's hearts for the further action of God's grace and the indwelling of the Spirit, who must finish the work begun in weakness, and fear, and trembling.(72)

In June 1898 the school at Darlington was closed and never again reopened. In November 1898, A. B. Shelly, editor of the "Mission Department" of The Mennonite and Secretary of the Mission Board wrote an editorial entitled, "Our Indian Mission—Its Present Needs," in which he said:

When Christ said to his disciples, 'The harvest truly is great but the laborers are few,' his words had a special reference to the wants of that time. But his words apply with equal force to the requirements upon the missionfield in our time, and with a certain amount of force to our own work among the Indians. The want of a greater number of able, devoted and consecrated men and women, who are willing to enter and remain permanently in our mission has all along been sorely felt…. Not unfrequently the Missionboard has been hampered in its work on account of an insufficient number of workers. It was on this account mainly that the Board felt itself obliged to discontinue the school at Darlington. And although the Board has decided to retain the station as a mission station, by stationing a missionary there, it has thus far been unable to find the proper person for that position. Should our efforts in this direction prove as unavailing in the future as they have in the past, the Board will no doubt be obliged, against its will, to relinguish [sic] this station entirely.(73)

In the summer of 1900 M. M. Horsch and his wife (Ottilie Dettweiler) returned to Darlington (after serving at Cantonment from 1893 to 1894 and Clinton from 1894 to 1900) and spent some time getting things back into shape. He visited the Indians and held a service in the school room and was asked by the superintendent of the government school to hold evening services with the children. But he found the Indians reserved and hard to approach. The old difficulty of not knowing the language was still a problem and Horsch lamented his lack of knowledge of Arapaho, saying, "I wish very much I could talk the Arapahoe language too, for one meets many Arapahoes and it is annoying when you have to sit with them unable to say a word." However, he remained optimistic that "there is still a work here for the Lord, and that with faithful, energetic work something may yet be done here for the cause of the kingdom. The government people are very friendly and obliging and with the help of the Lord their respect and esteem can again be won for the Mission."(74)

The Horsches remained at Darlington until New Year of 1902 but with their departure the Mission Board gave up the station. According to the Mission Board's report presented to the 1902 General Conference,

There was some work to do here, both with adult Indians as well as with the children in the government schools. But because there were only a few Indians in the proximity of Darlington, of whom only the fewest are living there, and these are served, like the children in the schools, by other denominations, and some of them are even baptized already by these denominations, thus the Board did not believe that it would be worthwhile for us to continue the work in Darlington any longer…. Nothing else remains for us than to leave Darlington with empty hands and leave to others the use of our improvements there. As promising as the prospects at Darlington once were, so however have the changed conditions of the Indians and their move to other locations defeated all hopes for successful mission work there. But the work, which was done at Darlington, was not futile. Because even if no congregation could be gathered here, so nevertheless a number of Indians, in particular those who attended our school there, have received impressions which will go with them through life and from which some of them will gain eternal blessing.(75)

1. See H. P. Krehbiel, History of the General Conference of the Mennonites of North America (Canton, OH: author, 1898); Alfred Habegger, "The development of missionary interests among the members of the General Conference of Mennonites of North America" (MA thesis, Bluffton College and Mennonite Seminary, 1917); Edmund G. Kaufman, The development of the missionary and philanthropic interest among the Mennonites of North America (Berne, Ind.: Mennonite Book Concern, 1931) ; and James C. Juhnke, "General Conference Mennonite Missions to the American Indians in the Late Nineteenth Century," Mennonite Quarterly Review 54 (April 1980):117-134.

2. John D. Miles, "[Letter to Rev. S. S. Haury]." 10 Dezember 1879, Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt, Feb. 1880, 10. All translations are the author's with the assistance of John D. Thiesen, archivist of the Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, Kansas.

3. S. S. Haury, "[Letter to the Mission Board]," 15 Juli 1880, Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt, Aug. 1880, 58.

4. S. S. Haury, Nachrichten, Aug. 1880, 58.

5. S. S. Haury, "[Letter to the Mission Board]," 3 Juni 1880, Nachrichten aus der Hiedenwelt, Juli 1880, 50.

6. S. S. Haury, Nachrichten, Aug. 1880, 58.

7. S. S. Haury, Nachrichten, Aug. 1880, 58.

8. S. S. Haury, Nachrichten, Aug. 1880, 58-59.

9. S. S. Haury, "[Letter to the Mission Board]," No date, Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt, Nov. 1880, 81.

10. S. S. Haury, Nachrichten, Nov. 1880, 82.

11. S. S. Haury, "[Letter to the Mission Board]," 19 Jan. 1881, Nachrichten aus der Hiedenwelt, Feb. 1881, 9.

12. S. S. Haury, "[Report]," Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1881 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1881), 75. Hereafter ARCIA.

13. S. S. Haury, Jahres-Bericht für 1881, 2. [This is a supplement to Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt.]

14. Haury, ARCIA 1881, 75.

15. Der neunzehnte February, 1882, auf der Mennoniten-Missions-Station, in Darlington, Indian Territory: 7. [This is a special supplement published by the Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt describing the fire that destroyed the mission building.]

16. John D. Miles, "[Report]" ARCIA 1883 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 64.

17. Miles, ARCIA 1883, 69.

18. Carl J. van der Smissen, "Nachrichten aus der Mission." Christlicher Bundes-Bote, Oct. 1882, 151.

19. Historical data General Conference Mennonite missions Oklahoma. [1938?] [Possibly put together by Mrs. G. A. Linscheid. Typescript.]

20. S. S. Haury, "[Report]." ARCIA 1882. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1882), 62.

21. Haury, ARCIA 1883, 69.

22. The main source for these names is G. A. and Anna Linscheid's Employes [sic] of the General Conference Mennonite mission in Oklahoma. Canton, Okla.: Mr. & Mrs. G. A. Linscheid, 1937.

23. Heinrich Voth, "Quartalbericht." Beilage zum Bundes-Boten [1st quarter 1883], 6.

24. "Cantonment." Beilage zum Bundes-Boten. [3rd quarter 1883], 1.

25. Agents at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency during the years 1880 to 1902 were the following: John D. Miles (1872-1884); Daniel B. Dyer (April 1884-August 1885); J. M. Lee (Acting Agent, August 1885-September 1886); G. D. Williams (September 1886-May 1889); Charles F. Ashley (May 1889-August 1893); A. E. Woodson (Acting Agent, August 1893-December 1899); George W. H. Stouch (January 1900-1906).

26. D. B. Dyer, "[Report]" ARCIA 1884 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1884), 71.

27. Dyer, ARCIA 1884, 75.

28. D. B. Dyer, "[Report]," ARCIA 1885 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1885), 81.

29. S. S. Haury, "[Report]," ARCIA 1885, 81.

30. The Halstead Fortbildungs-Schule or Halstead Seminary opened in 1883 in Halstead, Kansas and began receiving Indian students from Oklahoma in 1885. The Indian school was split off after a couple of years and continued east of Halstead on the Christian Krehbiel farm. See Mennonite Encyclopedia, s.v. "Halstead Seminary."

31. H. R. Voth, "Darlington," Mennonite, April 1887, 104-105; Voth, H. R., "Darlington," Mennonite, October 1887, 11.

32. A. B. Shelly, "A Trip to Indian Territory (Concluded)," Mennonite, September 1888, 177.

33. Shelly, "Trip," 180.

34. The Dawes Act or General Allotment Law of 1887 provided for the allotment of Indian Lands in severalty. The belief was that individual ownership of land would result in "civilizing" the Indians.

35. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field. Darlington," Mennonite, Feb. 1889, 70.

36. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field. Darlington," Mennonite, May 1889, 122.

37. H. R. Voth, "Reports from Our Mission Field. For First Quarter, 1889. Darlington," Mennonite, July 1889, 150.

38. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field. Extracts from the Reports of our Missionaries for Second Quarter, 1889. Darlington," Mennonite, Nov 1889, 26.

39. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field. Darlington," Mennonite, Dec. 1889, 43.

40. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field. Extracts from Quarterly Reports of Our Missionaries to the Mission Board. Darlington," Mennonite, April 1890, 106.

41. H. R. Voth, "Report of Superintendent Mennonite Mission." ARCIA 1889. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889), 312.

42. H. R. Voth, "Report of Superintendent of Mennonite Mission." ARCIA 1890. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1890), 185.

43. G. D. Williams, "[Report]," ARCIA 1887 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1887), 74.

44. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field. Darlington," Mennonite, March 1891, 91.

45. H. R. Voth, "From Our Missionfield," Mennonite, July 1891, 155. This was the Arapaho Sitting Bull, a leading promoter of the Ghost Dance, not the more well-known Sioux Sitting Bull. See Marlin Adrian, "General Conference Mennonite Missions and Native American Religions (Part 1)," Mennonite Life 44 (March 1989), 8.

46. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field," Mennonite, Oct. 1891, 6.

47. H. R. Voth, "From Our Mission Field," Mennonite, Dec. 1891, 22.

48. T. J. Morgan, "Supplemental Report on Indian Education," ARCIA 1889, 113.

49. Morgan, ARCIA 1889, 97.

50. Seger Colony was founded as a farming colony for Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians in March of 1886 by John Seger near Cobb Creek and Washita. Seger served as agent, farmer and school superintendent. Photos can be found at http://members.cox.net/teewood/SegerCol/segercolony.html

51. H. R. Voth, Mennonite, Dec. 1891, 22.

52. T. J. Morgan, "Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs," ARCIA 1891 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 56.

53. Morgan, ARCIA 1891, 68-69.

54. "Rules in Regard to Attendance of Indian Youth at School." ARCIA 1891, 159.

55. Morgan, ARCIA 1891, 70.

56. T. J. Morgan, "Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs." ARCIA 1892. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1892), 41, 50.

57. "From Our Mission Field," Mennonite, Nov. 1892, 14.

58. "Changes Among Our Mission-Workers," Mennonite, Mar. 1892, 46.

59. A. B. Shelly, "Annual Report of the Mennonite Mission Board," Mennonite, Feb. 1893, 38.

60. A. B. Shelly, "Annual Report," Mennonite, Feb. 1893, 38.

61. A. S. Shelly, "Report of the General Conference," Mennonite, Dec. 1893, 20.

62. A. B. Shelly,"Annual Report," Mennonite, Feb. 1893, 38.

63. A. E. Woodson, "Report of Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency." ARCIA 1894 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1895), 238.

64. A. S. Voth, "Extracts from Reports of Our Missionaries. From Missionary A. S. Voth's Report," Mennonite, June 1894, 70.

65. "Notes from Our Missionfield. From the Last Quarterly Reports of our Missionworkers," Mennonite, Jan. 1895, 30.

66. A. B. Shelly, "Report of the Secretary of the Mennonite Mission Board for the Year 1895," Mennonite, Feb. 1896, 38.

67. A. B. Shelly, "Report," Mennonite, Feb. 1896, 38.

68. "Notes From Our Missionfield, Taken From Late Reports of Our Missionworkers. Darlington," Mennonite, Nov. 1895, 14.

69. "From Our Own Missionfield," Mennonite, July 1897, 79.

70. "Mission Department," Mennonite, May 1898, 63.

71. A. B. Shelly, "Mission Board Meeting," Mennonite, June 1898, 65.

72. H. G. Allebach, "From Our Missionaries," Mennonite, Sept. 1898, 95.

73. A. B. Shelly, "Our Indian Mission.-Its Present Needs," Mennonite, Nov 1898, 15.

74. M. M. Horsch, "A Good Word from Darlington," Mennonite, Aug 1900, 86.

75. A. B. Shelly, "Bericht der Behörde für äussere Mission," Christlicher Bundesbote, 30 Okt. 1902, 4-5.