June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

Marvin E. Kroeker is professor of emeritus of history at East Central University, Ada, Oklahoma. He has published actively on topics of the American West and Mennonites. Among his works are Comanches and Mennonites on the Oklahoma Plains (1997).

In their four centuries of history Mennonites have pioneered geographic frontiers on four continents of the world. Beginning in 1683, European Mennonites began to migrate to North America. For over two centuries thereafter, members of this Anabaptist group were found in the vanguard of the western movement in the area of the present United States. After 1873, thousands of Mennonites left the steppes of Russia for the prairies and plains of the United States and Canada. Many of these German Russians participated in the settlement of the "Last Frontiers" in the American West, including Oklahoma.

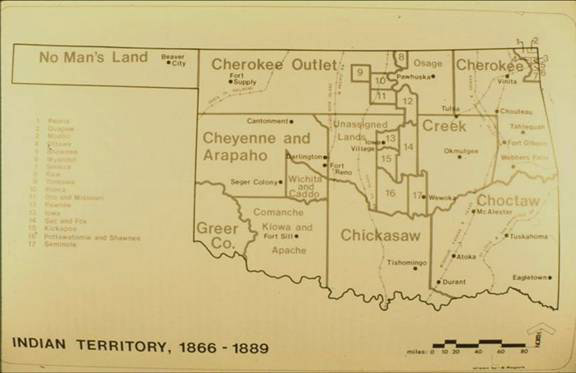

During much of the nineteenth century, present-day Oklahoma was designated as an exclusive territory for American Indians, and even today more than sixty tribes are represented in the population of the state. The eastern half of Indian Territory was the forced home of the Five Civilized Tribes, driven out of the southeastern states beginning in 1830. The tragic removal of the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles is a black chapter in our nation's history.

Soon after the Civil War, nomadic Plains tribes were forced by government treaties to accept reservation confinement. The reservation policy was adopted for the benefit of white farmers, railroad builders, miners, and others who were anxious to move onto Indian hunting lands in Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. In the Treaties of Medicine Lodge in 1867 the Kiowas, Comanches, Cheyennes, and Arapahos were assigned reservations in western Indian Territory. Other tribes were soon thereafter located in the north central and northeastern parts of the territory. The nomadic hunters were told to become settled farmers and homemakers, just like the whites. The prevailing view was that the only way to "civilize" the Indians and turn them into self-sufficient Christian citizens was to destroy tribal culture and Indian identity. This policy of acculturation under duress had serious consequences for the native people.

The reservation system was implemented with a military campaign that resulted in the massacre of Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle on the Washita River on November 27, 1868. This atrocity was led by George A. Custer and his Seventh Cavalry.(1)

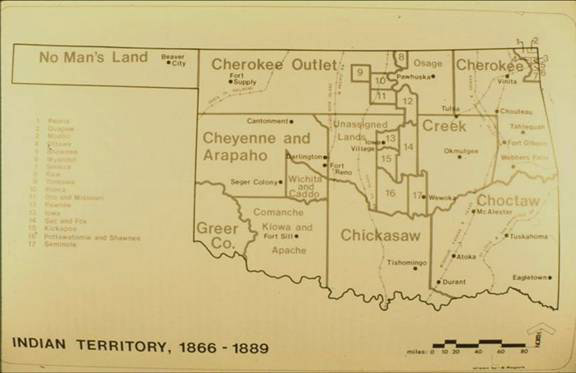

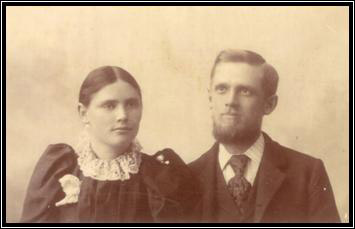

Susanna Hirschler Haury and Samuel S. Haury

It was during the reservation years that the first Mennonites came to Oklahoma. In 1880, twelve years after the Washita massacre, General Conference (GC) Mennonites began missionary work on the Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation. Fifteen years after that, the Mennonite Brethren (MB) established a mission among the Comanche Indians, placed on a reservation at the same time as the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. These were the first foreign mission programs for both branches of Mennonites. The tribes they worked with were considered among the most warlike of all the Plains Indians. At both places Mennonite missionaries were participants in events of historic importance in tribal and Oklahoma history.

Samuel and Susanna Haury, the first GC missionaries, arrived at the Darlington Agency in May 1880. Thereafter a stream of missionaries, teachers, and other workers came to work in the mission enterprise. Other denominations also sent missionaries, including Quakers, Methodists, Episcopalians, Baptists, and Mormons; however, during the early decades the Mennonites carried on the most extensive work among the two tribes. The government Indian agency was administered by a Quaker, who eagerly encouraged the Mennonites to help him carry out the government's new "peace policy" toward Indians. The task was daunting. The fact that they were representatives of a Christian church did not automatically engender feelings of trust. The Indians remembered too well that the man who led the charge at the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, J. M. Chivington, was an ordained Methodist minister.

The Haurys decided it was best to start working with the youth, educating them to walk the white man's road, while at the same time teaching them the tenets of the Christian religion. A frame mission and school building was erected to accommodate twenty-five Indian children and the missionary family. The Indian agent in essence forced the parents to enroll their children. The fledgling work suffered a severe setback when the school was destroyed in a tragic fire that took the lives of the Haurys' infant son and three Indian children. But the work went on, and soon expanded to include Cantonment, an abandoned military camp given to the peace church by the government. Haury transferred to Cantonment where he established a mission and agricultural school.

With the financial assistance of the government, a new school rose from the ashes at Darlington. H. R. Voth, a recent immigrant from Russia, was placed in charge of the work at this site. In the administration of his mission school Voth seems to have aligned himself closely with the government policy of destroying Indian languages and culture. The educational efforts were supplemented by sending Arapaho students to Mennonite communities in Kansas where they lived and worked on farms while attending public school and the Mennonite Industrial School at Krehbieltown, near Halstead.(2)

Although the Mennonites generally supported the government's assimilation program, there were times when they sided with the Indians against agency decisions. For example, in the 1890s agent A. E. Woodson, a non-Quaker, issued sweeping orders designed to break the power of the chiefs and to end traditional ceremonies and customs. Missionary Rodolphe Petter wrote a letter supporting Little Man, a Cheyenne who opposed Woodson's programs. The Indian agent immediately warned Petter that if he was siding with the Indians, "I shall know where to place you in the future."(3)

Eventually eleven mission stations were established by the Mennonites among the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. In the two decades prior to 1900 more than one hundred workers were sent to Indian Territory. Among the stations established were Shelly, Clinton, and Red Moon, up and down the Washita River from where we are meeting today. But the harvest of souls was meager. The memories of recent massacres and betrayals were too fresh to permit a ready acceptance of the white man's religion. Some were more open to the indigenous rituals associated with the peyote ceremonies, or the Ghost Dance prophecies of the coming of an Indian Messiah, along with the return of the buffalo, and a return to life as it was in the days before the coming of the white man. This was a period of transition, confusion, and turmoil in Indian society. First they were thrust on reservations, where virtually nobody knew the rules. Then, less than twenty years later, the reservations were broken up in favor of the allotment policy. Under this, Indians were scattered all over western Oklahoma on small parcels of land to make room for non-Indian homesteaders, which disrupted mission activities. To successfully introduce a new religion to people living under such chaotic conditions was virtually impossible. Another deterrent to progress may have been the perception that the missionaries were tools of the government's forced assimilation policy, a policy deeply resented by many tribal members.

It was eight years before the Mennonite missionaries could claim their first baptized Indian convert. Her name was Maggie Leonard, a seventeen-year-old mixed-blood Arapaho. According to James Juhnke, after two decades of mission work, only about forty converts had been baptized. Thereafter, he indicated, the number of conversions continued to be disappointing.(4) It was twelve years before the Mennonite Brethren gained their first Comanche convert at Post Oak Mission. Mission boards of all denominations at that time agreed that the plains Indians were the most difficult "heathen" to Christianize.

Maggie Leonard

Two missionaries gained wide scholarly acclaim for their contributions to our knowledge of Indian cultures and languages. Rodolphe Petter, a Swiss Mennonite who served at Cantonment from 1890-1916, put the Cheyenne language into written form and produced the first Cheyenne-English dictionary. H. R. Voth went to great pains to study the Arapaho language and folkways even while trying to destroy both in his mission boarding school. Ironically, the German Mennonites at the same time were fiercely determined to preserve their own language and culture in America. Voth wrote scholarly articles describing Arapaho and Hopi culture based on his investigations in Oklahoma and Arizona. But he got into trouble with the Hopis and his mission board when he sold valuable artifacts he had collected to the Field Museum in Chicago.(5)

Donald Berthrong, the leading living authority on the Southern Cheyenne, evaluated the GC missionary work as follows: "With a single exception, Cheyennes and Arapahos respected Mennonite missionaries because of the deep concern they displayed not only for their spiritual but also their temporal welfare." In addition to their preaching and education programs, he said, they "sought to instill a work ethic among the tribal people." Two Arapahos educated in Mennonite schools became tribal chiefs. "The sometimes stern pastors continued urging Cheyennes and Arapahos to educate their children, live in clean houses, farm their land, and abandon tribal ceremonies, the latter with limited success. More successfully than other sectarian missionaries, the Mennonites lived and worked among tribesmen frequently protecting them from their rapacious non-Indian neighbors."(6)

After twenty years of reservation life and programs, the government concluded that the policy was not leading to Indian assimilation and self-sufficiency. Thus they came up with a new policy. It was spelled out in the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, which brought an end to reservations in western Oklahoma. Under the provisions, all Indians were to be allotted up to 160 acres of their jointly owned reservation lands as private property. The law did not parcel out all the land to the Indians. The government decided to take some of it and give it to the whites. That portion was referred to as "excess" reservation land. Of course, it was "excess" only in the eyes of non-Indians—not the tribal members from whom the land was taken.

Making Indians independent farmers, and scattering them out more, it was now rationalized, would be the best way to destroy tribal communal life and "Americanize" the first Americans. The opposition of tribal leaders like Red Moon was ignored.

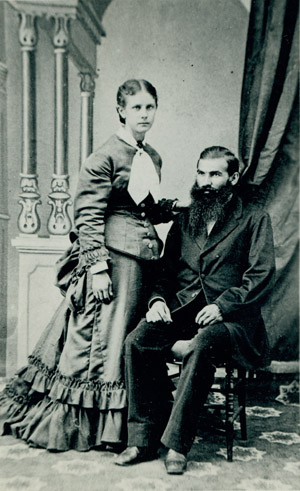

While the allotment policy was unfolding, Congress authorized the opening of a portion of Oklahoma to non-Indians that had not been designated as part of any Indian reservation. It had earlier been taken from the Five Tribes' holdings, and was referred to as the Oklahoma District, or the Unassigned Lands. A presidential proclamation declared that the District would be opened to homesteaders on April 22, 1889. This was the first of a series of "runs" that followed. To give equal opportunity to all persons interested in getting 160 acres of free land, it was decided to settle the area by a novel procedure—a land run, or race. People could line up at the borders, and when the signal was given, the race was on, and whoever got to a given quarter-section first would get the land.

Fifty thousand people participated in the Run of 1889. They raced on foot, on horseback, on wagons, and on a train. By evening nearly every homestead claim and town lot had been taken. Some settlers sneaked in ahead of time, selected a choice homestead and then hid out until the rush approached. They then put down their stake and got it "proved up" before others got there. Those who entered the territory sooner than they legally could do so were the original Oklahoma "Sooners." Prior to the time that football became the established religion in Oklahoma, "Sooners" was a derogatory term.

Every April school children across Oklahoma re-enact the Land Run of '89, and there are all kinds of activities celebrating this exciting event. Jerald Walker, a Creek-Cherokee Indian, has provided an alternative view of the land runs. Indian people, he wrote, find it "difficult to celebrate an invasion. It was a perfectly legal invasion from the non-Indian perspective, but nothing more than another land grab by property hungry non-Indians from the Native American perspective."(7) If Mennonite participants in the Runs had any moral or ethical qualms about acquiring lands taken from Indians, often by deceit, intimidation, and bribery, they did not let it deter them.

There were only a few Mennonites that participated in the Run of '89. One of these was my maternal grandfather, Kornelius Zielke, born in the Waldheim village of Molotschna Colony, Russia. In 1875 he emigrated to near Galva in central Kansas. Seven years later he married Aganetta Ediger, who also came from Russia. By 1889 the young couple had two children, and struggled financially. From a friend, Kornelius learned about the chance to run for free land in the Indian Territory, and decided to make the race. On the morning of the opening day he and his brother-in-law, John Ediger, lined up on the northern boundary waiting for the signal to start. The land had been surveyed into 160 acre claims with quarter and section markers set. At high noon the signal came and Zielke and Ediger took off. I do not know whether they went on foot, by wagon, or on horseback. But both succeeded in staking claims to homesteads located three miles east of present Hennessey. They traveled only about two and one-half miles before they hit pay dirt. They paid a small filing fee, registered their claims and returned to Kansas grateful to God for his protection and for the opportunity to begin a new life in Oklahoma.

The Zielkes did not immediately prosper in the new land. In 1891 when my mother was born, they were still living in a dugout. Nearly destitute, Zielke walked all the way from Hennessey to the Galva area, a distance of over 170 miles, to borrow money from relatives to provide food for his family. I am sure he enjoyed the run into Oklahoma much more than he enjoyed that walk out. In 1898, because there were too few Mennonites to establish a church, and because they felt isolated from friends and relatives, the Zielkes sold out and moved to Corn.

Mennoville church

Another small group of Mennonites acquired homesteads in 1889 near the western boundary of the Unassigned Lands, not far from the Darlington Mission. I believe that at least four Mennonites made the Run from this location. They were Joel Sprunger, Peter Isaac, Isaac Penner, and Anna Penner. Their homesteads were located five to eight miles north of El Reno. Soon about sixteen families, including some missionaries from Darlington, established Mennoville, the first Mennonite Church in Oklahoma. Their sanctuary, constructed in 1893, remains the oldest existing Mennonite church building in Oklahoma, although services were discontinued in 1953. For many years it was on the National Register of Historic Places, and served as a landmark on Highway 81 north of El Reno. When it was improperly moved to a historic park in El Reno, it lost its National Register designation.(8)

On April 19, 1892, the three and one-half million "excess" acres of the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation were opened to homesteaders. By that date the approximately 3,300 Cheyennes and Arapahos had selected their allotments. These allotments, the government said, would be the vehicle to Indian progress and self-sufficiency. However, studies show that by the early 1930s two-thirds of all land allotted to Indians under the Dawes Act had fallen into the hands of non-Indians. In too many instances unscrupulous whites took advantage of Indians unschooled in financial matters and cheated them out of their lands for virtually nothing. And in too many cases the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other government officials did nothing to stop such abuses.

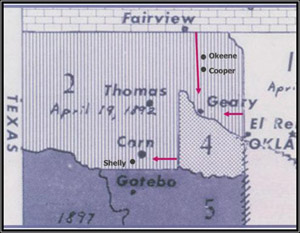

Mennonite settlements after Cheyenne-Arapaho opening

Much of the land in western Oklahoma was regarded as unfit for farming, thus only about 25,000 participated in the Land Run of 1892. Many homesteads could still be claimed months after the opening day. Also, this land was not free. Settlers were required to pay $1.50 an acre for their quarter sections.

Included among the earliest homesteaders in western Oklahoma were a host of hopeful Mennonites, most of whom were recent Germans from Russia who had originally settled in Kansas. The Mennonite settlements in the Cheyenne-Arapaho country were initially concentrated in three counties: Blaine, Washita, and Custer. In Blaine County, three separate communities emerged: Cooper, Geary, and Okeene.

Rev. Cornelius Grunau and about twenty co-religionists settled in the Cooper area. They organized a Mennonite Brethren church in the winter of 1892-93. Although the exact founding date is obscure, this apparently was the first MB church in Oklahoma. The church membership had more than doubled by 1896, but thereafter it began to decline as many left the region because of crop failures. Indeed, it appears that fertility of the Mennonite people at Cooper far exceed that of the soil. For example, John Janzen and his wife could raise only meager crops of wheat but managed to produce a bumper crop of sixteen children. Somehow they managed to cram them all into a small three room house. By 1902 the Mennonite community had dwindled to such an extent that the church was disbanded.

Mennonites helped to establish Okeene and formed the Ebenfeld MB church. Many of the settlers came from the Ebenfeld community in central Kansas. The Okeene church still functions today.

General Conference Mennonites helped establish the community of Geary, originally called Garden Plains. A number of settlers came from Halstead, Kansas, but others arrived from nearby mission stations. In 1898 the settlers loaded their country church onto four wagons and hauled it into town, thereby establishing the first church in Geary. It was only in recent years that the church closed its doors.(9)

The Mennonite movement into Washita County was instigated by the reports of General Conference missionaries in western Oklahoma. John J. Kliewer established the Shelly Indian Mission on the Washita River in 1889. His reports to Mennonite communities in Kansas told of rich bottom lands and fertile virgin prairies, and urged families to come join him after the land was opened to non-Indians.

Although the land on which Shelly Mission and his home were located had already been granted to the Mennonite church, Kliewer decided to have it registered in his name. Avoiding any potential charges of "Soonerism," he left the mission on the morning of the Run and lined up on the border at Seger Colony, eight miles to the east. When the signal was given to begin the race, he hurried back home and drove a stake in his yard. His brother Henry also filed a claim. Sixteen more Mennonite heads of families filed claims in 1892. This vanguard group set into motion a wave of migration that led to the development of the largest Mennonite settlement in Oklahoma. One band of eight homesteaders filed claims along Coffee Creek, west of present Corn, in October 1892. They followed a route from Buhler, Kansas to Caldwell, and then on south to Cooper. From there they journeyed southwestwardly to Shelly. It was a two-week trip by wagons. Henry H. Flaming, who later became a respected MB minister, was in the group, although he was too young to file a claim. He became a squatter on a quarter section across the road from his father, hoping no one would file a claim to it before he reached the legal filing age of twenty-one. No one did. And then he did.

Most of the Washita County Mennonites came from Reno, Harvey, and Marion counties in Kansas. All had been in the United States for less than twenty years; a few for less than one year.(10) One group came from a further distance—continuing an unbelievable trek that had taken them from their homes in the Ukraine, the Kuban, and the Volga to Turkestan, and then later to America. These were the followers of the charismatic but misguided Claasz Epp, who in 1880 had led them on a pilgrimage into Central Asia to make ready for the Second Coming of Christ. Instead of meeting the returned Messiah, they met disillusionment, destitution, and death. My paternal great-grandparents were caught up in this strange venture, and my great-grandmother lies buried somewhere in the stark desert expanse near Tashkent. Thirty-eight families who survived that debacle came to the United States in 1884, settling in Kansas and Nebraska. Ten years later a number of them took up homesteads near Shelly. Thirty-six became charter members of the Herold Mennonite Church, located southwest of present Corn. Michael Klaassen, a veteran of the Great Trek, served as minister. With their own land and a church, they thought that finally they could settle down for good. Unfortunately, it was not to be. During World War I, Klaassen, an outspoken religious pacifist, received so many threats from superpatriots in the area that he fled to Canada. About fifty of his fellow church members soon followed.(11)

Corn — spelled Korn until 1918 when it was anglicized due to World War I pressure — gradually replaced Shelly as the economic, social, and religious hub of an expanding and thriving community. Founded in 1903 (post office in 1896), the town grew up around the Mennonite Brethren Church. The congregation's first church, built in the spring of 1894, was a dugout twenty by forty feet with sides built up a few feet with sod. In 1902 the MB General Conference convened in Korn, with, reportedly, three thousand people from Canada and the US in attendance. The church continued to grow until it reached its peak membership of 720 in 1924. In 1905 the Bessie MB Church was established for the benefit of members living on the western fringe of the large settlement.

On August 24, 1894, twenty families from the Alexanderwohl and Hoffnungsau communities in Kansas organized Bergthal, the first General Conference church in the area. Soon there were three additional GC congregations: Herold, mentioned earlier, Sichar, and Salem.

And northeast of Corn in Custer County, the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren (KMB) established a church. Gordon Friesen, novelist, defender of radical causes, and friend of Woody Guthrie, grew up in this church community. His book, Flamethrowers, centers on a young Kansas Mennonite who rebels against what he perceives to be the stifling influence of Mennonite culture. Menno Duerksen, another writer and Friesen's cousin, also came from this tiny KMB community. A United Press International correspondent and newspaper reporter, he wrote a revealing book of personal stories that insightfully pictured what his life was like in a very restrictive Mennonite environment.(12)

Between 1893-1920 eight Mennonite churches—GC, MB, KMB—were organized within an eight mile radius of Corn. Three are still active: Bessie (now located in Cordell), Corn, and Herold. Based on my study of the federal census, there were 891 Mennonites living in the greater Corn community in 1900. By 1910 the Mennonite population had grown to 1,730. These figures are based on my identification of "Mennonite" names and, thus, are not infallible.

There seems to have been little interaction between the Mennonite settler community and the natives of the area, especially after the Shelly Mission was closed. On the other hand, Comanche delegations from Post Oak Mission frequently attended MB conferences, singing conventions, and Sunday School conventions when held at Corn or Fairview. Over the years, some Comanche students attended the Corn Bible Academy, established by the MB Church in 1902.

The Old Order Amish also sought land in western Oklahoma. A few families arrived in 1893 but the major influx came after 1898. By statehood (1907) there were over 100 Amish scattered between Thomas and Hydro.

The largest Land Run took place on September 16, 1893, when the Cherokee Outlet was opened to homesteaders. More than 100,000 people raced to claim a quarter section of the rich prairies. There were roughly 36,000 claims available for settlement, which meant that only one-third of those who made the Run would be able to get land. People lined up along the boundaries weeks and even months before the opening. 1893 saw the beginning of a four-year drought. It was an extremely hot summer. On the days before the Run the temperatures reached 108 degrees. Fifty cases of heat stroke were reported, with at least ten deaths. There was a great shortage of water for people and horses.

When the signal was given to start the race, everything was helter skelter, pell mell. Rigs broke down and horses stumbled and fell, but the thundering mass moved on. Several men and women were thrown from their horses and trampled to death at the start of the race. Four men were shot and killed by soldiers for starting on the Outlet before the hour of noon arrived. Before the Run, the "Strip" was burned bare in some places to keep Sooners from hiding in the grass.

Mennonites again were in the front ranks of those who surged into the newly opened territory. They played a significant role in the founding and early development of a dozen or more communities, including Deer Creek, Fairview, Goltry, Kremlin, Lahoma, Lucien, Medford, Meno, North Enid, Orienta, and Ringwood. Those who staked claims had to pay $1.50-$2.50 per acre, depending on the zone in which they settled. Most Mennonites settled in the middle zone where the price was $2.00 an acre. Not all of the Mennonite land seekers were successful in filing claims. Ben Decker stated that he knew of several who had lost choice lands because they were not willing to fight it out with challengers who falsely asserted prior claims. Martin Just, Henry Bartel, John and Will Hein, and Fred and Carl Wichert, all from the Ebenfeld community in Kansas, gathered at Caldwell a week ahead of the Run. After the race began they traveled all afternoon until nightfall searching for unclaimed land. They found none, and were forced to return to Kansas empty-handed. Several returned a few months later and bought up relinquishments near Fairview. A number of Mennonites acquired land in Oklahoma by this method.(13)

According to one estimate, eighty-five percent of the Mennonites in the Outlet had lived in or near Marion County, Kansas, before moving to Oklahoma. When the rush ended, the larger Mennonite concentrations were found west of Enid in the Meno-Ringwood-Goltry area; north and south of Fairview; near Medford; and in the North Enid-Kremlin area. A sizeable number of the settlers around Meno, Ringwood, and Goltry were Polish Mennonites who previously resided near Canton and Moundridge, Kansas. The Canton Mennonite Church lost about 150 members in the last half of the 1890s, most of whom came to Oklahoma. The New Hopedale Mennonite Church at Meno soon became the largest General Conference congregation. The founder of Meno, David Koehn, meant to name the town Menno, after Menno Simons, but in filling out the post office application papers, he apparently left out one "n."(14)

In 1895 Fairview MBs built two churches to accommodate the wide-spread settlement: Nord (North) and Süd (South) Hoffnungsfeld (Hopefield). The combined membership was 171. Rev. Jacob Becker, a founder of the Mennonite Brethren Church in Russia in 1861, served at the South Fairview MB Church.

A small number of Russian Mennonites who had originally settled in Henderson, Nebraska, participated in the Run of '93. Severe drought conditions apparently drove them to look to the Enid area for a new start, only to find that it was just as dry there. Others, including Peter Regier, leader of the Henderson MB Church, followed in 1897 and bought relinquishments north of Enid. The long drought had finally ended by the time Regier arrived, and he became a big booster of the Enid area. Writing in the Zionsbote, he declared that "the land is as good as any in Nebraska and the climate is much better." And, in an apparent use of "ministerial license," he claimed that "the summer nights are always cool with refreshing breezes." With the arrival of Regier, the North Enid MB Church was organized April 5, 1897.

Medford and nearby Deer Creek became a center for both MB and GC immigrants from Russia. In 1899 John F. Harms, one of the most influential figures in MB history, settled on a farm two and one-half miles northeast of Medford. A farmer, historian, and ordained minister, he printed and edited the Zionsbote, a weekly German newspaper widely read by MBs in the United States and Canada. The paper was printed on a press located on his farm. It was later moved to Hillsboro, Kansas. The GC church established at Deer Creek survives to this day.

Jet, Manchester, and Newkirk were settlement areas for the "Old" Mennonites. Church of God in Christ Mennonites (Holdeman) founded churches near Fairview and Chickasha. All told, twenty Mennonite churches were established in the Cherokee Outlet territory between 1893 and 1907.

Mennonites continued to search for land in Oklahoma even after the major land openings. Some tried to eke out a living in the arid Panhandle, called No Man's Land until 1890 when it was attached to Oklahoma. The first to arrive came in the early 1900s. Most came from Buhler and Inman, Kansas, but some from Medford and Fairview. This was free land for those willing to take a gamble. The Hooker, Adams, Balko, and Turpin communities included GCs, MBs, and KMBs. These Panhandle Mennonites were a hardy breed. Once they got a toehold in the sod, not even the fierce dust storms of the "Dirty Thirties" could drive them out.

Other GC and MB Mennonites found their way to Gotebo and Eakly, drawing settlers from adjacent Washita County. Mennonites did not move into eastern Oklahoma until after statehood.(15)

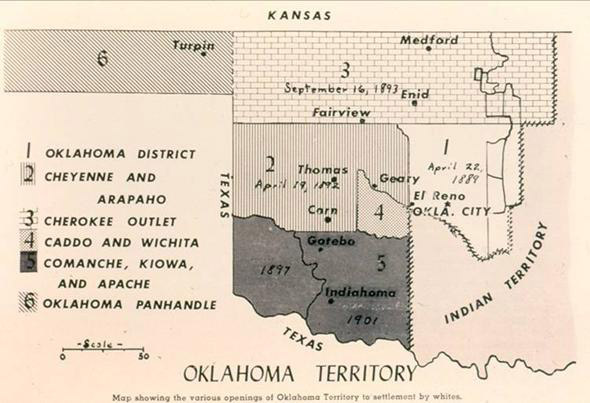

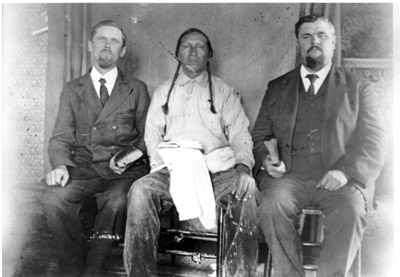

The Mennonite presence and influence in southwestern Oklahoma was extended with the founding of Post Oak Mission in 1895-96. Established among the Comanche Indians near Indiahoma, it was the first foreign mission of the Mennonite Brethren Church of North America. The first missionary appointed to the field was Henry Kohfeld, a teacher from Hillsboro, Kansas. His main accomplishment was to gain permission from Chief Quanah Parker to build a "Jesus House" on his land. After twelve years of devoted but generally unproductive effort, he was replaced by Abraham J. and Magdalena Becker from Fairview. Born in Kuban, Russia, Abraham was the son of MB founder Jacob Becker. Whereas Kohfeld could not claim a single baptized convert, Becker baptized seven in his first year. By the time he retired 40 years later, he had baptized 430 converts at Post Oak.

Magdalena and Abraham Becker (Photo Credit: CMBS, Fresno, CA)

Missionary Becker and M. M. Just with Mo-Wat (No Hand), first Comanche baptized at Post Oak Mission (Photo Credit: Oklahoma Historical Society)

A friendly relationship developed between the Beckers and the renowned Chief Quanah Parker, despite the fact that Quanah was a polygamist and a proponent of the peyote religion. The chief had the grave of his white mother, Cynthia Ann Parker, removed from Texas to the Post Oak Mission cemetery, and urged his people to follow his mother's religion. However, according to Magdalena Becker, he never gave up his old religion. After Quanah's death, To-pay, one of his seven wives, and several other family members joined the mission church.

Critical to the success of Post Oak was the service of Magdalena as field matron in the Indian Service. For twenty-eight years she trained Indian women in the skills of housekeeping, child care, cooking, sewing, and health care. Fluent in the Comanche language, her work broke down barriers and made the Comanches amenable to the Beckers' religious message. According to William T. Hagan, a leading authority on the Comanches, the Beckers developed Post Oak Mission into "arguably, the most successful one in western Oklahoma." In 1957, over the protests of many Comanches, the mission and historic cemetery were relocated in Indiahoma to make room for a projected Fort Sill missile range. Today, the Post Oak MB Church is a self-administering congregation.(16)

By the end of the territorial period in Oklahoma, a distinct and vibrant Mennonite culture had taken root. When Oklahoma entered the Union in 1907, there were forty-four Mennonite and Amish churches in the former Indian Territory. The various branches were represented as follows: 22 GC; 12 MB; 3 MC; 2 KMB; 2 Holdeman; 2 Old Order Amish; and 1 Amish-Mennonite. Most Mennonites viewed the future with an air of confidence and optimism. But in the wake of the strong anti-German and anti-pacifist prejudice that manifested itself during World War I, many began to submerge or mask their ethnic and religious identity. They faced growing Americanization pressures similar to what the Indians were going through: pressures to adopt a new language, new customs, and identify with mainstream cultural expectations. Interest in preserving their history and distinctive culture declined. Fortunately, since about the 1960s there has been a growing interest among Mennonites to trace their ancestral roots and to rediscover their unique and remarkable heritage.

In 2000 there were 45 Mennonite and Amish congregations in the state, virtually the same number as in 1907. However, only a dozen or so of the original churches remained. Representation by branches was as follows: 14 GC; 13 MB; 5 Old Order Amish; 4 Holdeman; 2 MC; 1 Beachy Amish; 1 Kleine Gemeinde; and 5 others.(17) The statistics include five American Indian Mennonite churches whose origins date back to the mission period. Five Indian churches—Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche—where over a century later God is still worshiped and obeyed. Any evaluation of the Mennonite mission endeavors among the Native Americans in Oklahoma should not overlook that fact.

Historically, Oklahoma Mennonite life revolved around three institutions: family, church and school. The essential element that sustained all three was land. Of course, land— reverence for Mother Earth—is important in Indian cultures as well. Virtually all Oklahoma Mennonites can still trace their family heritage directly to the land. However, today the vast majority are not farmers. If agriculture has been the foundation of Mennonite culture, can the historic Mennonite values, beliefs, and traditions survive in a highly urbanized and secular society? Sadly, a tide of social, cultural, and religious conformity is eroding our distinctive and unique Mennonite identity. It will take a consistent effort by the current generation to preserve the Anabaptist/Mennonite heritage in a recognizable form and to successfully pass it on to the next generation. That is our charge.

1. Good analyses of the reservation system in western Oklahoma are found in Donald Berthrong, The Cheyenne and Arapaho Ordeal: Reservation and Agency Life in the Indian Territory, 1875-1907 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976); and William T. Hagan, United States-Comanche Relations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976).

2. Christian Krehbiel, "The Beginnings of Missions in Oklahoma," trans. by Elva Krehbiel Leisy, Mennonite Life (July, 1955), 108-113; Herbert M. Dalke, "Seventy-five Years of Missions in Oklahoma," Mennonite Life (July, 1955), 100-107.

3. Berthrong, Cheyenne and Arapaho Ordeal, 214.

4. James C. Juhnke, "General Conference Mennonite Missions to the American Indians in the Late Nineteenth Century," Mennonite Quarterly Review (April 1980), 118. Juhnke provides a scholarly and generally critical evaluation of the GC mission enterprise in Oklahoma.

5. Juhnke, 130.

6. Berthrong, personal letter to author, October 24, 1988.

7. Jerald Walker, "The Difficulty of Celebrating an Invasion," in Davis D. Joyce, ed., "An Oklahoma I Had Never Seen Before": Alternative Views of Oklahoma History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 18.

8. Helena Wehmuller, "History of the Mennoville Mennonite Church," June, 1976, Unpublished manuscript, 1-4.

9. Personal interview with P. C. Grunau, July 23, 1952; Marvin E. Kroeker, "The Mennonites of Oklahoma to 1907" (Unpublished master's thesis, University of Oklahoma, 1954), 37-40.

10. Kroeker, "The Mennonites of Oklahoma to 1907," 40-41.

11. John W. Arn, The Herold Mennonite Church: 70th Anniversary, 1899-1969 (North Newton: Mennonite Press,1969), 5-17. For a more detailed account of Michael Klaassen's travails during World War I see Marvin E. Kroeker, "'In Death You Shall Not Wear It Either': The Persecution of Mennonite Pacifists in Oklahoma" in Joyce, ed., "An Oklahoma I Had Never Seen Before," 80-100.

12. Gordon Friesen, Flamethrowers (Caldwell: The Caxton Printers, 1936); Menno Duerksen, Dear God, I'm Only a Boy (Memphis: Castle Books, 1986).

13. Kroeker, "Mennonites of Oklahoma to 1907," 50-63; Personal interview with Ben Decker, July 17, 1952; Henry J. Wiens, The Mennonite Brethren Churches of North America (Hillsboro: M.B. Publishing House, 1954), 75.

14. Douglas Hale, The Germans from Russia in Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980), 37; David Haury, Prairie People: A History of the Western District Conference (Newton: Faith and Life Press, 1981), 131-134.

15. Kroeker, "Mennonites of Oklahoma to 1907," 64-70; Haury, Prairie People, 129-130.

16. For the history of Post Oak Mission see Kroeker, Comanches and Mennonites on the Oklahoma Plains (Winnipeg: Kindred Productions, 1997). The Hagan quote is found in the "Foreword" he wrote for the above book.

17. Donald B. Kraybill and C. Nelson Hostetter, Anabaptist World USA (Scottdale: Herald Press, 2001), 265.