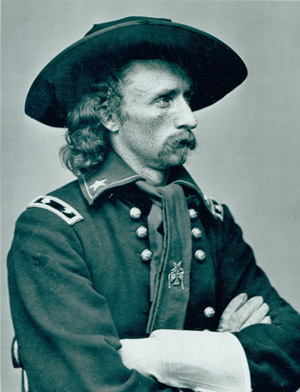

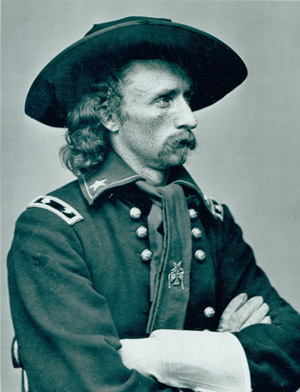

George Armstrong Custer

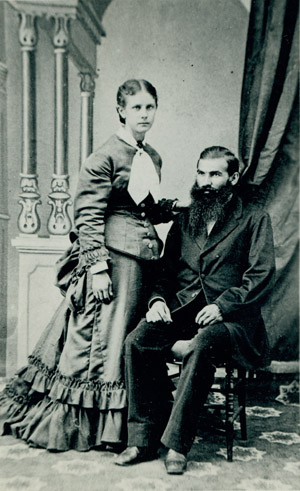

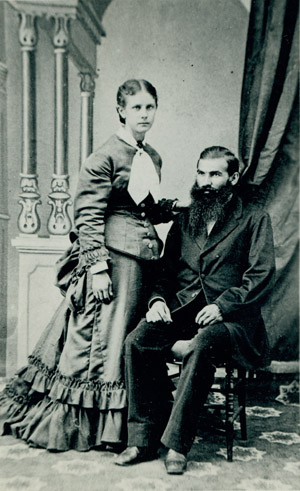

Susanna Hirschler Haury and Samuel S. Haury

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

George Armstrong Custer |

Susanna Hirschler Haury and Samuel S. Haury |

The prevailing popular narrative of Indian-White relations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries tells of two kinds of invading attacks on the Plains Indians. One attack was military and one was missionary. Though they used different methods, both attacks intended to destroy Indian ways.(1) Two representative invaders were General George Armstrong Custer and missionary Samuel S. Haury. In November, 1868, Custer's Seventh Cavalry destroyed Peace Chief Black Kettle's band at the Washita River. Twelve years later, in 1880, Mennonite missionaries Samuel and Susie Haury began an educational and spiritual ministry at the Darlington Agency on the Canadian River. Custer and Haury invite comparison. What did their respective missions offer in terms of destruction and/or empowerment for the Indians?

Although George Armstrong Custer came from Pennsylvania German stock, his first recorded encounter with Mennonites was in 1873, five years after the Washita massacre/battle. Custer brought a delegation of Indians, "nineteen chiefs and three squaws," to the national capitol to meet and exchange gifts with President Ulysses S. Grant. In the president's office that day was Peter Jansen, recent Mennonite immigrant from Russia who had come to request privileges for his people. Custer invited Jansen to accompany his colorful delegation to the theater that evening. Jansen was impressed by both General Custer and the "stoic aborigines." In his later memoirs, Jansen revealed that he knew little about the Washita massacre or about Custer's attitudes toward the Indians: "Poor General Custer!" wrote Jansen. "Three years later he met his untimely death through the treachery of his red friends, whom he had always treated so well."(2)

One of Custer's biographers, Milo Milton Quaife, invented a hypothetical "pacifist-minded" Mennonite ancestry for Custer. Quaife thought it ironical that such a warrior hero would emerge out of the notably "phlegmatic and peaceloving" Pennsylvania German environment.(3) Custer was born in 1839. In 1857, before his eighteenth birthday, he entered West Point Military Academy. He graduated at the bottom of his class, 34th of 34 graduates. During the Civil War he became the youngest general in the Union army. He fought in every engagement of the Army of the Potomac and established a reputation for daring, bravery, and blind luck. He was a flamboyant publicity hound who wore exaggerated dress and fixed his hair "in long glistening ringlets liberally sprinkled with cinnamon-scented hair oil." After the war he served as a cavalry fighter in the Plains Indian wars.

Custer's national fame rested in large part on the Seventh Cavalry attack in 1868 on the band of Black Kettle, Cheyenne peace chief. National Park Service tour guides at Fort Larned today present the massacre, which they prefer to call a "battle," as a successful "search and destroy mission."(4) The Seventh Cavalry found the Indians' winter camp; killed Chief Black Kettle and his wife, along with several dozen other Cheyenne men, women and children; destroyed some 800 ponies; took fifty-three women and children captive; and got away with the loss of two officers and nineteen enlisted men.(5) Custer wrote an exaggerated self-serving account of the Washita massacre that helped establish his reputation as a dashing military hero. Just eight years after his success at Washita, Custer died at the famous battle of the Little Big Horn in Montana. He was only thirty-five years old. He became the American mythical tragic hero of "Custer's Last Stand."

Samuel S. Haury was eight years younger than Custer, born in 1847 near Ingolstadt, Bavaria. He moved to Illinois with his parents. Haury attended the new Mennonite seminary in Wadsworth, Ohio (1868-71), and the Rhineland Mission School in Barmen, Germany (1871-75). Unlike Custer, Haury was a disciplined and distinguished student. Until 1880, when he and his wife, Susie L. Hirschler, undertook their mission work at the Darlington Agency, Haury was an enthusiastic promoter in Mennonite circles for the missionary cause. His booklet, Letters Concerning the Spread of the Gospel, was published in 1877. He argued that missionary work was mandated by Scripture, and that it would have civilizing effects upon the non-Christians. Missions would be the means for spiritual renewal among Mennonite churches that were trapped in formalistic legalism. Although he was optimistic about the prospects for progress, Haury was not a flamboyant publicity hound like Custer. He was rather diligent, persistent, and somewhat stodgy. Lacking "Custer's luck," Haury suffered a long series of illnesses. He survived two train wrecks, a stunning lightening flash, eye disease, spinal meningitis, pleurisy, and other difficulties.

Haury was the first Mennonite missionary to be sent out by any of the Mennonite denominational agencies. He directed the mission work first at Darlington and then at the former military post at Cantonment. The work of education, evangelism, and agricultural development among the Cheyenne and Arapaho was far more difficult than he had imagined. He never really mastered the Arapaho or Cheyenne languages. He won and baptized no converts. He resigned from the mission in disgrace in 1887 after becoming involved in an adulterous affair with a married woman missionary. He then went to medical school and became a medical doctor in Moundridge and Newton, Kansas. Samuel and Susanna Haury were the parents of seven children, one of whom died as an infant when the new mission building at Darlington burned to the ground. In 1913 the Haury family moved to Upland, California, where he died in 1929. Haury lived forty-seven more years than did Custer.

Custer and Haury had radically different attitudes toward the Indians. Custer believed the Indians were incapable of civilization. They were a menace that "infested" the Plains, and they deserved obliteration. The Indian was, Custer wrote, "a savage in every sense of the word, . . . one whose cruel and ferocious nature far exceeds that of any wild beast of the desert." Attempts to civilize the Indians invariably would fail. Where attempted, "it has been at the sacrifice of power and influence as a tribe, and the more serious loss of health, vigor and courage as individuals."(6) Custer did express admiration for Indian "wonderful skill in feats of horsemanship," and for their fighting "with a desperation and courage which no race of men could surpass."(7) The image of Indians as great fighters magnified the victories of their white conquerors. Custer excused his own cavalrymen for killing Indian women and children at the Washita. "In a struggle of this character it is impossible at all times to discriminate, particularly when, in a hand-to-hand conflict . . . the squaws are as dangerous adversaries as the warriors."(8)

Haury's image of the Indians contrasted sharply with that of Custer. Haury was influenced by a biblical and theological doctrine of creation that had been part of his missionary education at Wadsworth and Barmen. The Indians were created by God and belong to Him. God loves the Indians and calls them to Himself. The Indians already knew about God and the Holy Spirit. They needed to learn about and to accept Jesus, who revealed God's love in his death and resurrection. Haury quoted John 10:16, "But there are other sheep of mine, not belonging to this fold, whom I must bring in." Indians were "by nature a noble and gifted people" unlike many other "heathen."(9) They could be Christianized and civilized.

Haury was repulsed by some of the traditional Plains Indian religious ceremonies. In 1877 when he first attended a Sun Dance ceremony, Haury was shocked by the special tortures of fasting young men who danced around a pole to which their flesh was attached with a rope. The "heathenish" ritual bespoke "an unrecognizable sense of sinfulness and an undefined longing for salvation and peace." Alas, "these poor Indians are serving Satan with all their self-inflicted pain." The antidote, according to Haury, was the gospel of God's love. "Oh, may that day come when the light of the Gospel will illuminate the hearts of the benighted Heathen."(10) Haury and his generation of missionaries all believed that the Sun Dance and other traditional ceremonies would come to an end when the Cheyenne and Arapaho people were Christianized.

Haury believed that Christianity and civilization went hand in hand. If the Indians were to be civilized, they would also have to be Christianized. Central to the civilizing process was the challenge of education for literacy and for agricultural production. By the time Haury arrived at Darlington, the invading white men had destroyed the large bison herds that were essential to the traditional Indian economy and way of life. Mennonite missionaries assumed, as did all other social reformers of the late nineteenth century, that Indians needed to become productive small farmers living on individual homesteads. The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 attempted to achieve this goal, at the same time that it made most of the Cheyenne/Arapaho reservation land available for white settlement.

Haury attempted to be an advocate for Indian rights. At Cantonment in 1884 some cowboys murdered a Cheyenne Indian, Running Buffalo, who just a week before had shared a Sunday meal with the Haury family. In the aftermath of the murder, Haury played a mediating role that helped avert a wider range war among cowboys and Indians. Haury testified at the trial of the murderers in Wichita, Kansas. The court exonerated the cowboys. Haury had to return to Cantonment with the news that the Indians must return some ponies that had been given to them in exchange for Running Buffalo's life.(11) It was not an easy task to advocate for the white man's religion in a situation of oppression and injustice inflicted by whites upon Indians.

There is an ironical disparity between the idealistic and progressive goals of early Mennonite missionaries and the realities of their encounter with the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. The harvest of converts and of churches planted was disappointingly small. The work of education, however, did bear some fruit in empowering some Indians to successful adaptation to modern ways. Several generations of Indians became leaders in school and church. Cheyenne Christian women as well as men adapted the images and forms of Christian worship to sustain their own distinctive identity as Indians.(12) In some ways the life and ministry of Lawrence Hart, Cheyenne Peace Chief and Mennonite minister, represents a culmination of possibilities of fashioning a creative accommodation on the boundaries of Cheyenne tradition and modern American life.(13)

Custer and Haury, the warrior and the missionary, participated in assaults upon the ways of Indians on the plains. But those assaults were vastly different from each other. If the theme of "irony" is appropriate for evaluating the Haury's missionary efforts, a contrasting label of "demonic" might apply to the Custer and the Seventh Cavalry. Today as one stands in the Washita river valley just outside the town of Cheyenne, Oklahoma, one can imagine the awful slaughter of humans and horses that followed Custer's surprise attack on Chief Black Kettle's sleeping encampment. That murderous attack was an evil event, and it was supported and conditioned by Custer's racist views of the Indians. The fact that Custer's military assault was welcomed and celebrated by the American public is shameful. Mennonites today cannot responsibly share Peter Jansen's view of Custer. Custer and Haury did have much in common as white men intruding onto Indian Territory in the late nineteenth century. But to conflate these differing intrusions into an undifferentiated assault by whites upon Indians is to obscure a more complex reality.

1. For examples, see Colin G. Calloway, First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1999), 350, and the video series, "500 Nations," episode 5.

2. Peter Jansen, Memoirs of Peter Jansen (Beatrice, NE: author, 1921).

3. George A. Custer, My Life on the Plains. Edited with introduction by Milo Milton Quaife (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), x, xi, xv.

4. Based on an account by guides at Fort Larned, Bethel College history class field trip, Fall 2001.

5. Mary Jane Warde, Washita (2nd edition Cheyenne, OK: National Park Service, 2005).

6. Custer, My Life, 22, 23. Custer did acknowledge that whites, "similarly born and bred," would also be savages. But, of course, whites were born and bred to civilized life.

7. Custer, My Life, 251, 335.

8. Custer, My Life, 336.

9. Haury used the term "heathen," or "Heiden," in ways typical of his time to refer to non-Christians. He also wrote of "Christian heathen" whose attacks had harmed the Indians.

10. Samuel S. Haury, "Three Days in an Arapaho Indian Camp," Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt, Oct. 1877, 73-75. Translated by Hilda Voth.

11. The event was reported in the Christlicher Bundesbote, 1 June 1884, 7.

12. For an account of the complex legacy of Christianity among Plains Indians, see Luke Eric Lassiter, Clyde Ellis, and Ralph Kotay, The Jesus Road: Kiowas, Christianity and Indian Hymns (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

13. See the forthcoming biography of Lawrence Hart by Raylene Hinz Penner, to be published in the C. Henry Smith series at Bluffton College. For a general narrative and assessment of the early decades of General Conference Mennonite missions to the Indians, see James C. Juhnke, " General Conference Mennonite Missions to the American Indians in the Late 19th Century," Mennonite Quarterly Review (April 1980), 117-134.