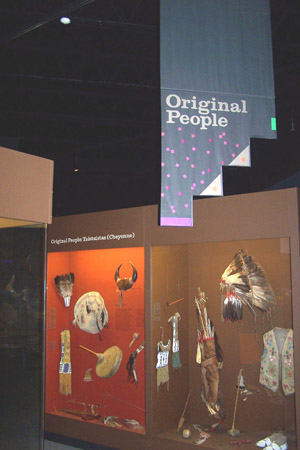

Fig. 1: "Original People" thematic banner area in Kauffman Museum permanent exhibition "Of Land and People".

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

John M. Janzen is professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas and from 1998 until 2006 he was the director of the Kansas African Studies Center. His primary research field is African health and healing. From 1982 until 1992 he served as director of Kauffman Museum, and led the team that conceptualized, designed, and built the permanent exhibition "Of Land and People."

Fig. 1: "Original People" thematic banner area in Kauffman Museum permanent exhibition "Of Land and People".

At Kauffman Museum at Bethel College, one of the seven banner theme areas of the permanent exhibition "Of Land and People" is entitled "Original People" (Fig. 1). This section features a hundred artifacts in a dozen cases about the Cheyenne of the Great Plains. The discerning viewer will note the companion banner theme "Immigrant People," (Fig. 2) and the adjacent banner themes of "The Prairie," (Fig. 3) "Living off the Land," "Home and Family," "Mennonite Life," and "Encounters across Cultures." In this essay I explain why and how this exhibit area on the Cheyenne was included in the 1980s exhibition planning and implementation project at the Kauffman, who was involved in its preparation, and how it took on its character in relationship to the wider exhibit.

Fig. 2: "Immigrant People" banner area, at entrance to "Of Land and People" exhibition.

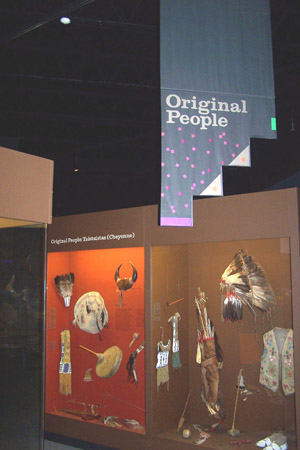

Fig. 3: "The Prairie" banner area.

In the Kauffman's permanent exhibition the Cheyenne -or Tsistsistas as they are known to themselves, meaning "the people, or original people"--stand as a cultural shorthand for the general native history of the Americans, and in particular for that of the Great Plains of North America.(1) Because of their migratory history on the Great Plains, they illustrate a variety of ecological adaptive strategies. Their story includes foot hunting and gathering, sedentary cultivation and villages, from 1700 on horse-mounted nomadic hunting, and from 1870 on, life on reservations, the rural countryside, and urban America. Another reason for the inclusion of the Tsistsistsas in the Kauffman's exhibition--and for the collections in the museum-- is that native Cheyenne and immigrant Mennonites have known each other as two peoples, among many now living on the plains, and have experienced a unique and many-sided relationship for over a century. The logic that led to the inclusion of a Cheyenne exhibit area seems appropriate today in light of the March 2006 Clinton, Oklahoma, conference "Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Mennonite: Journey from Darlington." An earlier version of this essay was presented at the conference.

The permanent exhibition at Kauffman Museum was developed(2) in the 1980s by a team consisting of Museum staff, Museum Association members, Bethel College faculty, and special consultants. Professor Oswald Goering had been director-developer in the 1970s to raise funds for a new building and to create the Kauffman Museum Association. When I became director in 1983, the development initiative continued with a focus on the permanent exhibit, staffing, and programming. The exhibit development team included historians Robert Kreider and James Juhnke, biologist Dwight Platt, anthropologists Rachel Pannabecker and myself, art historian Reinhild Janzen, artist designer Robert Regier, graphic designer Ken Hiebert, landscape architect Harold Neufeldt, and educator Lorene Goering. Later, exhibit builders Chuck Regier and David Kreider joined the team.

In the course of planning the project, the thought emerged that the unique collections on the Cheyenne, reflecting Mennonite work and relationships with Cheyenne, should be incorporated into the permanent exhibition. Karl Schlesier, anthropologist, then at Wichita State University, a well-known scholar on the Cheyenne, and Bill Red Hat, today the Arrow Priest or Arrow Keeper, were invited to assist with the "Original People" section of the exhibit. After being invited to participate in this way, Bill Red Hat approached his grandfather, Edward Red Hat, the then Arrow Keeper, to seek acceptance of the collaboration with the Kauffman Museum. He smoked a pipe and may have consulted the arrows, and prayed to the Great Spirit, before agreeing to participate. Red Hat and Schlesier conferred with the planning team on the exhibit concept and the selection of appropriate artifacts. They drafted all the relevant texts. They have continued to advocate for the exhibition as both a legitimate expression of Cheyenne identity and history, and an example of intellectually masterful cultural interpretation.

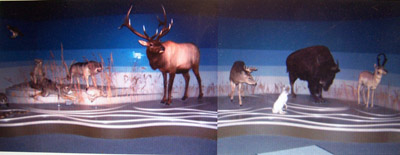

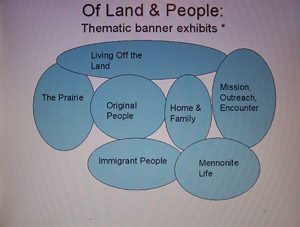

Fig. 4: Depiction of spatial relationship of all thematic banner areas in the permanent exhibition "Of Land and People." The exhibition may be studied both for the story within the themes, as well as for comparative or mutually enhancing exhibit sections that span two overlapping thematic areas.

The "Original People" section is situated within the overall exhibition "Of Land and People" so as to relate to other exhibits around it. Of Land and People is organized in thematic and comparative rather than sequential or chronological arrangement of exhibits (Fig.4). This feature was a selling point of the exhibition project to the National Endowment for the Humanities that contributed significant funding for its planning, implementation, and interpretation, and for an endowment challenge match. One of the major thematic comparisons is that of "Original People" and "Immigrant People." Exhibits on migration and settlement, worldview and religion, making a living, and raising children may be compared across cultures. "Original People" and "Prairie" are juxtaposed around exhibits on the ecology of the great plains grasslands, and its non-human inhabitants-- grazers, carnivores, migratory birds, micro-organisms, and the manner in which the Cheyenne show a historic people adapting in various ways to that environment. "Original People" and "Living off the Land" show contrasting modes of cultivation and of the culture of the horse in Cheyenne nomadic hunting and in settler ranching. "Original People" and "Home and Family" offer comparative and contrasting exhibits on children, clothing, play and toys, and men's and women's roles in Cheyenne and immigrant Mennonite American societies. These juxtaposed exhibits offer opportunity for reflection on the dynamic nature of contrasting civilizations, changing cultures, and diverse environments--in particular the North American Great Plains.

The Kauffman Museum collections reflect the interaction experience by Cheyenne, long time inhabitants of the Central Plains, and the recently arrived European Mennonites of Central Kansas. Just after the Cheyenne had been forced onto their Oklahoma reservation in the 1870s, Henry R. Voth, Samuel S. Haury, and others were invited to direct school programs for the Cheyenne and Arapaho at the Darlington Agency near El Reno. Out of this contact were founded mission stations at Cantonment, Hammond, and Fonda (1882, 1898, 1907 respectively). For the northern Cheyenne in Montana, mission stations were founded around 1904 at Lame Deer, Busby, Birney, and Ashland. nbsp;Mennonites ministered to the Indians' needs of food, shelter, health, education, and spiritual nurture. Missionaries learned the culture of the Indians and deeply appreciated its richness, its ceremonies, and oral traditions. For nearly fifty years Rodolphe Petter (1865-1947) studied the Cheyenne language, worked on a dictionary of the Cheyenne language, and translated the Bible into Cheyenne. Most of the Cheyenne artifacts in the exhibits were gifts by Cheyenne men and women to missionaries Haury, Voth, Linscheid, Habegger, and Petter, and their families. Bill Red Hat expressed his pleasure that so many of the Cheyenne cultural artifacts in the Kauffman were documented as having been given as gifts by Cheyenne individuals. The cradle board (Fig. 5) given by his great grandfather Little Man to Rodolphe Petter on the death of a Cheyenne child was particularly noteworthy in this regard.(6)

Fig. 5: The illustrated cradleboard was presented to Dr. Rodolphe Petter in 1892 by the family of the Arrow Keeper, Little Man, at the death of a child. The cradleboard had been in this family for many years. Babies were protected by these cradleboards. They provided comfort, as well as allowing the mother to carry the baby safely on horseback or to leave the infant for a short time. [wood frame, cotton lining, satin ribbons, hide fringe, trade glass beads on hide]Donor: Bertha K. Petter KM 6254.80

Visitors to the Kauffman will find deep histories of both immigrant Mennonite and Cheyenne peoples. An electronic world map addresses the question of why Mennonites live in pockets all over the world through twelve historic moments of upheaval, migration, and settlement.

Fig. 6: Tsistsistas in Time and Space: Map of Northern and Central Great Plains of North America showing migration and settlement history of Cheyenne or their ancestors over 2,500 years.

The long-term history of the Cheyenne is depicted similarly in a panel "Tsistsistas (Cheyenne) in Time and Space" (Fig. 6). The Tsistsistas have inhabited the grasslands for 2,500 years, adapting to different regions. From 1000 BC they lived as foot hunters. Then, after 100 AD, as small-scale farmers. After the introduction of the horse to North America by the Spaniards in 1700, they learned to depend on it for buffalo hunting. From 1869, the Tsistsistas were forced on reservations. Today they live mainly in Oklahoma and in Montana. This reconstruction of Cheyenne history benefits from Schlesier's research on the Masaum, the oldest recognizably Cheyenne ceremony, last performed in 1927, but thought to go back to the early agrarian or even pre-agrarian era in Minnesota and the northern Plains.(3) Cheyenne ceremonies--the Masaum "earth giving," and Arrow Renewal, as well as the Sun Dance--recognize the special characteristics of the Plains region, its particular animal and plant spirits.. The viewer can compare the commonalities and differences with other worldviews, attitudes about the earth, and cultural aspects of Mennonite farmers and others of European descent.

The juxtaposition of "Original People" with "Living off the Land" invites the museum visitor to consider the commonalities and differences of historic Cheyenne adaptation with the story of the transformation of the prairies by the technology of the Industrial Revolution. The prime icon of this exhibit area is the John Deere "sod-busting plow." Working the earth, seeding, harvesting, and threshing are each depicted in pre-industrial and industrial techniques and tools from the Museum's collections. Sickle, cradle scythe, and McCormick Reaper demonstrate the transition from hand made tools to industrially manufactured machines that were needed to "conquer" the prairie.

This exhibit faces the cultivation and hunting section of "Original People." The Cheyenne and other peoples of the Plains were cultivators from ca. the 10th century to the 17th century before they became horseback hunters. Exhibits feature Plains food preparation, a two dimensional depiction of the Biesterfeld archeological site on the Cheyenne River in North Dakota that illustrates an earth lodge settlement typical of how they lived, and a large exhibit on prehistoric and more recent nomadic hunting. This latter exhibit faces an exhibit on settler ranching, both featuring centrally the culture of the horse imported from Asia (Fig. 7 & Fig. 8).

Fig. 7: "Cheyenne Hunting" exhibit featuring a saddle, bridle, spurs, two guns, and other equipment used with Plains Indian horsemanship. A prehistoric bison hunting pit is shown, as well as a parfleche bag.

Fig. 8: "Ranching" exhibit facing "Cheyenne Hunting," the Euro-American settler culture of the horse, as practiced by many immigrant Mennonites and their neighbors in Central Kansas.

The text of the hunting exhibit in "Original People" interprets the Cheyenne attitude toward nature.

Tsistsistas believe that plants are both physical and spiritual. Eating plants makes animals and humans part of the plant community. Because game animals sustain themselves with the potency of plants their flesh is regarded as sacred. Eating animal flesh makes humans part of the animal community. When an animal is killed, only its physical form is slain. The animal spirit must be released to the Earth Spirit. Hunting is a sacred ritual ruled by game, not by the hunter. Animals are celebrated as beautiful, mysterious, powerful and benevolent. Spirits of plants and animals may grant a human special knowledge and protection. Physical parts of plants and animals are used in healing.

The exhibit presents the several contrasting world views that account for natural and human adaptation to the Great Plains, both in terms of the energy flow and the spiritual dimensions of life. No graphic image is offered to convey the jarring "worldview" of the sod-busting plow as an ecological force, yet in many ways it brings to an end the prairie as an ecosystem. At the intersection of "Prairie," "Living off the Land," and "Original People" is "The Prairie Food Web" (Fig 9), an ecologist's graphic view of energy transfers in the Prairie, prepared by biologist and team member Dwight Platt. The source of all energy is the sun, which provides energy for the growth of lower organisms--bacteria, grubs, insects--that are absorbed by vegetation and eaten by birds and some mammals. The food web transforms energy from lower forms--herbivores-- to the carnivores that consume them. Gyre falcons and eagles represent the birds; bison, wolf, and puma the mammals.

Fig. 9: "Prairie Food Web" depicted at the interface of the Prairie and Living off the Land.

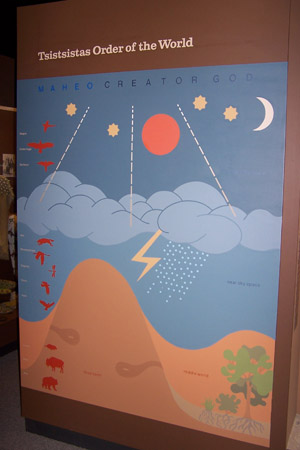

Fig. 10: "Tsistsistas Order of the World"

The "Tsistsistas Order of the World" (Fig. 10) may be compared to the Prairie Food Web. It is depicted in a large color painting where "Original People" faces the ranching, barbed wire, and sod-busting plow exhibits of "Living off the Land." This graphic, inspired by Schlesier and Red Hat, was visualized by exhibit designer Robert Regier. It shows some of the same birds and mammals, now in the characteristic hierarchy of worlds of many native North American world views. At the top, under Maheo-God, is the Blue Sky Space, home of the magpie, golden eagle, gyre falcon, stars, sun and moon). This is sacred space, inhabited by unique constellations that indicate particular events and determine the cycles in the ceremonial calendars. Near Sky Space is inhabited by whooping crane, dragonfly, raven, hawk, and wolf. Whooping crane travels north and south, coming with Thunder in the spring, nesting in the north; also associated with thunder, dragonfly is a messenger of spring associated with thunder, and changing seasons; raven is curious and clever; airborne hawks are predatory and swift; wolf, two stars, and thunder are represented as a wolf who belongs to the sky spirit Nnoma. Middle World is the realm of roots, grasses, and trees. Deep Earth is inhabited by badger, buffalo, bear, caves and caverns. Badger mediates prayers to earth spirits for the satisfaction of wants, needs, and protection. Buffalo is an important game and spiritual animal. Bear hibernates, by doing so he gets into deep earth, therefore is close to the earth spirit.

Fig. 11: This cradleboard was in Charles Kauffman's South Dakota museum, attributed to "Sioux." However others say it is or could be Cheyenne. Bill Red Hat and Karl Schlesier interpret its intricate arrangement of the colorful beadwork as a northern Plains ritual cosmogram.

The "Tsistsistas Order of the World" is also visually presented in a striking cradleboard (Fig.11) for which Red Hat and Schlesier provide a detailed interpretive text.

The keepers or powers that Maheo has placed at the four corners of the universe to protect it are positioned at the Southeast, Southwest, Northwest, and Northeast, thus an eighth turn from the cardinal directions. In a recent Cheyenne ceremony for the "Return to the Earth" of repatriated human remains, at a burial site in the Cheyenne Cultural Center, Clinton, Oklahoma, these four corners were saluted or invoked by Cheyenne chiefs (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: Cheyenne chiefs dedicate the northwest corner of universe at Cheyenne Cultural Center Return to the Earth site, March 31, 2006.

This exhibit case (Fig. 13) includes beaded eagle feather fans, rattles, drums, headdresses, spirit shields, sweetgrass, and pipes for smoking tobacco, all objects that are used in Cheyenne ritual to invoke the powers of the universe. The text prepared by Schlesier and Red Hat explains general Tsistsistas theology.

Fig. 13: Invoking the Powers exhibit case, Kauffman Museum

The universe as created by Maheo includes hestanov, the visible world, and matasoomhestanov, the invisible world of spirits. In Maheo's order, all natural life forms have physical and spiritual form. Upon death, physical form becomes matter. Spiritual form is indestructible and permanent. Spirits of animals return to sacred caverns and the protection of the Earth Spirit. From there they may be released to once again join physical form. Tsistsistas spirits travel in the spirit world but may join physical form again to become another human in the visible world.Life in the world depends on cosmic power, exhastoz, emanating from Maheo. Exhastoz is in the power of the sun, in water, in air, and in the earth. These potencies are protected by powerful spirits. The annual Tsistsistas ceremonies commemorate and maintain Maheo's original order. The spirit world is also addressed through prayer, ritual painting, song and ceremonials. Ritual smoking of tobacco serves as a way to communicate with Maheo and the spirits. Sweetgrass and sage are also used ritually for purification.

Red Hat stressed that none of the articles in this exhibit are in and of themselves sacred, thus there was no problem with exhibiting them according to Cheyenne codes. But he said that the pipes needed to be displayed lying at the bottom of the case, with the stone heads detached from the stems, as they are when they are not being used. They must not be attached to the wall of the exhibit case. Other ritual objects are identified and interpreted in the exhibit. The shield and its cover, of cotton, is painted with a rainbow or sky, a moon, and a sun of the universe (Fig. 14). Nine eagle feathers are sewn to the cover. Four mark the four corners of the universe. In the center appear a bear and two dragonflies, images that express the owner's dream obtained in a vision quest. The two 19th century spirit rattles (Fig. 15) come from major Cheyenne ceremonies. The left one shows engraved images of the four corners of the universe, the sun, the moon, the symbols of the sun dance altar. The right one bears an engraved and painted spirit image.

Fig. 14: Vision shield cover. Donor unknown. KM 14.

Fig. 15: Two ceremonial rattles. One rattle bears an engraved and painted spirit image. The other rattle shows engraved images of the four corners of the universe, the sun, the moon, the symbols of the Sun Dance altar. Donors Bertha K. Petter (KM 4447) and David Habegger KM 6137.6).

Several of the exhibit cases show the household tools, personal effects, and clothing of men, women, and children in the Kauffman's collections. Some of these artifacts are excellently documented to demonstrate the close personal ties between the Mennonite mission workers and the Cheyenne. A few of these are shown here along with the identification of the individuals from whom they originated. Red Hat and Schlesier have organized these materials into gender specific categories and offered extensive characterizations of the lives and roles of women, men, and children. Hide scrapers used by Mrs. Living Bear and her daughter Eva Blackbird (Fig. 16), an arrow quiver made by Vohokass around 1909 (Fig. 17), and the case devoted to children's games and toys (Fig. 18) represent these social realms.

Fig. 16: Two fleshing tools (ca. 1820-1900) were used to scrape meat and flesh from buffalo hides. The elk antler tool shows bundles of incised lines, marking events and ages of family memers. The cloth-wrapped meat scraper was used for 80 years by Mrs. Living Bear, then for 25 years by her daughter Eva Blackbird. Museum donors are Bertha Petter (KM 6254.5), Rev. G.A.Linscheid for Eva Blackbird (KM 96), and the Alfred Habegger family (KM 6137.29)

The roles of Tsistsistas men, women and children are manifest in tools, clothing, musical instruments, games, toys. Maheo's order demands that the sexes of the species be together. Both men and women are the custodians of the world, assisting Maheo to keep the world alive.

In the 19th century Tsistsistas world men did the heavy physical work, as in hunting and defense, but women could participate. In hunting ceremonies women often did game-calling and game-atoning sacrifices. The killing was done by men. Women distributed the game taken, fed the animal spirits and prepared the slain animals for food or for equipment such as hides, clothing, tents, and harnesses.

Fig. 17: Around 1900 Vohokass (Eugene Standing Elk, d. 1926) made the quiver and bow case. The bow and 52 arrows date from ca. 1825. Some were used in ceremonies, some in killing buffalo, and some in warfare. Donor: Bertha Petter, KM 6254.83

Women took care of the household tasks, but could fill roles according to preference and personal creative drive. The positions of shamans and priests were divided equally between men and women. The interdependence between men and women is symbolized by the male thunder spirit and the female Earth spirit. The thunder spirit initiates regeneration in spring through thunderstorms and moisture, while the Earth Spirit makes the earth, including plants and animals, available for rebirth. Each is essential for the continuation of life.

A child is a gift from the spirit world. The spirit of an ancestor on the father's or mother's side returns and joins physical form in the baby. Tsistsistas religion does not allow abortion. It is regarded as the murder of a relative. Children are much pampered by parents and grandparents. Physical punishment is considered an offense against the child's spirit. Although from a certain age on children are expected to help their parents, they are allowed much time to play.

Fig. 18: Mrs. Limpy's medicines. The medicines were all gathered near the Black Hills, South Dakota. They were first owned by Mrs. Limpy's great-great-grand-mother. Mrs. Limpy presented her medicine to missionary Alfred Habegger in Busby, Montana in 1925 when she was 69 years old. The large bag is made of buffalo skin sewn with sinew. The painted designs are nearly worn off by use. Small bags are made of antelope skin and cloth. Different glass trade beads identify the contents of each bag. Donor: Marden C. Habegger. KM 6146.5a-g.

It is fitting to conclude with a reflection on the integral place of Kauffman's Cheyenne collections and the exhibition in the on-going relationship of Cheyenne and Arapaho to Mennonites and the wider world. In recent conversations, fellow anthropologist Karl Schlesier emphasized that the Kauffman's Tsistsistas exhibition had borne the test of time and criticism because its creation was grounded in the double legitimacies of good scholarship and the blessing of the Cheyenne arrow priest. In addition, the collections represent legitimate gifts and acquisitions made by individuals and families who held the well-being of the Cheyenne people and their culture in high regard.

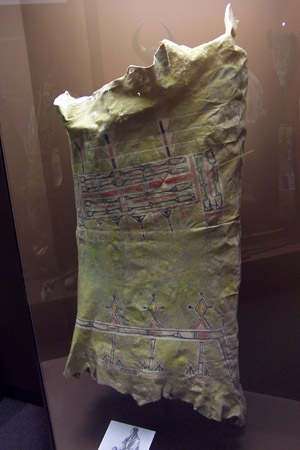

This historical and continuing relationship between Cheyenne and Mennonites exists at a number of levels: between individuals, within families, and institutionally. Individuals are perhaps too numerous and varied to mention, but friendships have been long-lasting and as friendships everywhere continue to be nurtured by reunions and encounters. Families have been intertwined by marriage and offspring who combine in their beings the dual traditions of Cheyenne or Arapaho and Mennonite. Also, the families that worked with the Cheyenne became acquainted, acquired cultural knowledge and artifacts, donated them, and continue to celebrate Cheyenne culture. A prime example of such a family is the children and grandchildren of Rev. Alfred and Mrs. Habegger. Alfred Habegger, long-time missionary to the Northern Cheyenne, lived with Cheyenne, was fluent in Cheyenne. The two Habegger sons, David, who became a Mennonite minister, and Marden, who became a physician, likewise grew up fluent in Cheyenne, playing with Cheyenne children. They too maintain a keen interest in Cheyenne affairs until the present. The artifact acquisition lists in the Kauffman Cheyenne collections reveal significant donations, such as Mrs. Limpy's medicine bundle (lower right) and Julia Yellow Horse Shoulderblade's ceremonial dress (center of case) (Fig. 19). David's daughter Rachel, who became an anthropologist, and wrote a dissertation at Ohio State University on Great Lakes trade ribbons, is now the director at Kauffman Museum and continues in administrative and scholarly work to cultivate the relationship to Cheyenne and native American communities and individuals. The painted hide engraved and painted by Hooomohe (a Sioux woman married to a Cheyenne man) and presented to Dr. Rodolphe Petter in 1900 is a gift that also reflects the mutual respect and appreciation of donor and recipient in a long-standing relationship (Fig. 20).

Fig. 19: ca. 1900. Worn by Julia Yellow Horse Shoulderblade when a young girl on festive occasions. She (1913-1973) was a prominent Cheyenne Mennonite leader. Donor, Julia Yellow Horse Shoulderblade KM6254.22.

Fig. 20: Painted hide, ca. 1870. Engraved and painted by Hooomohe, a Sioux woman married to a Cheyenne man. Presented to Dr. Rodolphe Petter around 1900. Women painted geometrical designs on hides which they used as robes, undercoverings, or blankets. The full meaning of the design is no longer known. It is thought that the whole figure represents a bison, with its several elements being part of the animal's body. Donor: Bertha Petter, KM6254.78.

The Kauffman Museum exhibition continues to radiate the scholarly and ceremonial work of the Schlesier/Red Hat relationship, and continuing connections that this has yielded. Numerous scholars and students have joined Schlesier and Red Hat in seeking to better the life of the Cheyenne and native Americans. Christina Loehn, a German anthropology student in action anthropology and medical anthropology at the University of Kansas, conducted doctoral research under Schlesier and my direction, on the diabetes epidemic among Cheyenne, and developed an action plan to combat it. Sybille Schlesier, daughter of Karl and Claire Schlesier, conducted research and wrote a dissertation for the University of New Mexico on Bill Red Hat as a story teller and the place of story in the maintenance of Cheyenne culture.(4)

The Cheyenne / Mennonite relationship is perhaps most dramatically embodied in the work of Lawrence Hart, Cheyenne Peace Chief, member of the Council of 44 Chiefs, Mennonite minister, and Bethel graduate. Married to Betty Hart (nee Bartel), of the Plautdietsch tradition of Hillsboro, Kansas, Lawrence and Betty's children Nathan, Cheyenne artist, and Connie, Cheyenne lawyer, demonstrate the family dimensions of Cheyenne and Mennonite connections very vividly. At the Cheyenne Cultural Center in Clinton, Oklahoma, further evidence is seen of the Bethel/Mennonite and Cheyenne connections. The linguistic work of Rodolphe Petter is on display and put to practical use in the Cheyenne language lab at the Center. A current exhibit shows the similarities between Mennonite peace principles and Cheyenne traditional restorative justice. Hart's leadership role on the NAGPRA national board and in the Return to the Earth initiative demonstrates the benefits of working ties between Cheyenne institutions and ecumenical groups, in particular the Mennonite Central Committee (Fig. 21).(5)

Fig. 21: Lawrence Hart, left, introduces NAGPRA Director Sherry Hutt, Erica Littlewolf of Return to the Earth, and Rachel Pannabecker, Director, Kauffman Museum, for a panel on museums, repatriation, and memorials.

Kauffman Museum's Tsistsistas--Original People section in the permanent exhibition "Of Land and People" is an attempt to represent and honor a people in our midst whose culture demonstrates a deep and ancient and wise relationship with the created universe. Kauffman Museum is fortunate to have received from many individuals and families the artifacts and accompanying stories that show this culture, and reveal the friendships and working relationships between people. Kauffman Museum and its wider public are fortunate indeed to have received the expertise and authority of the Schlesier/Red Hat team in the interpretation of the collections. The exhibit affords the means for continuing interpretation and demonstration of the richness of Tsistsistas life and wisdom.

1. One small exhibit section shows a sampling of the collections and in representative cultures (a few terra cotta heads from the Toltec empire, a Zuni pot from the Southwest, spears from the hunter-gatherer Chulupi and Moro of the Paraguayan Chaco, and a quilled Plains Indian body ornament)

2. For a fuller account of the design team and its process, see my 1987 article "Bethel's Museum: A Centennial History" Mennonite Life.Vol. 42,1, pp. 31-38.

3. Karl Schlesier, Wolves of Heaven: Cheyenne Shamanism, Ceremonies, & Prehistoric Origins. Norman: Oklahoma University Press. 1987.

4. Sibylle Schlesier. Stahot'sewoómss: I'll see you again. A Study in the working of collaboration: The narratives of Bill Red Hat, Cheyenne keeper of the arrows. 2005. University of New Mexico PhD Dissertation

5. United Native Ministries Council (Mennonite Church USA) should be mentioned also as an example of continuing Cheyenne and Mennonite linkages.