June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2006

vol. 61 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

author bio

Much of the following was originally written by Dave Graber for an article in The Hymnology Annual, Mr. Vernon Wicker, editor, 1995.

The story of the Cheyenne hymnbook(1) is one of adaptability and perseverance in the face of intense cultural pressure. Government attitudes in America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were especially hostile toward Native American culture. And while Christian missionaries were generally advocates for the various tribes they served, bridging the gap when conflicts arose with the broader government and society, they also inevitably acted as agents of cultural change. Christianity was packaged in the confines of "civilized" western culture. Through boarding schools, adoption, and travel away from the tribe, the new generation of Native people faced a rapidly changing cultural climate spreading even to the roots among elders on isolated reservations.

Indigenous music was only one small aspect of that larger cultural change. As Native Americans were taught of Christ and Christianity, they were hearing a new kind of music utterly foreign to their own musical understandings. The result was a new genre of music: indigenous Christian hymns. The lyrics reflect the spiritual understandings of Christianity and the melodies and rhythms include aspects of Plains Indian music and European music in varying degrees.

Yet historians and ethnologists seem to have paid little attention to this phenomenon for several possible reasons.

First, indigenous Christian hymns were not considered truly "Indian." Robert Lowie describes "a Crow imitation of a Baptist hymn" on an early wax cylinder recording of a Crow indigenous hymn made in the 1930s.(2) Others in the Native American Christian community have described receiving songs inspired by the sounds of European church music,(3) implying that the European hymns represent the celebration arts format through which God speaks. The theology expressed in the lyrics mirrors the theology of European hymns.(4) Recognizable melodic phrases from European hymns are sometimes actually incorporated into indigenous hymns.(5) The atmosphere of hostility between Christian and Native religion practitioners has led to rejection of this expression by both parties in the conflict between cultures.(6) Truly, the indigenous expression of Christian hymnody has been influenced by its European predecessor. The European standard of celebration arts for Christian worship was the model for songs one should hear from the Creator in a dream or vision along the new Jesus road.

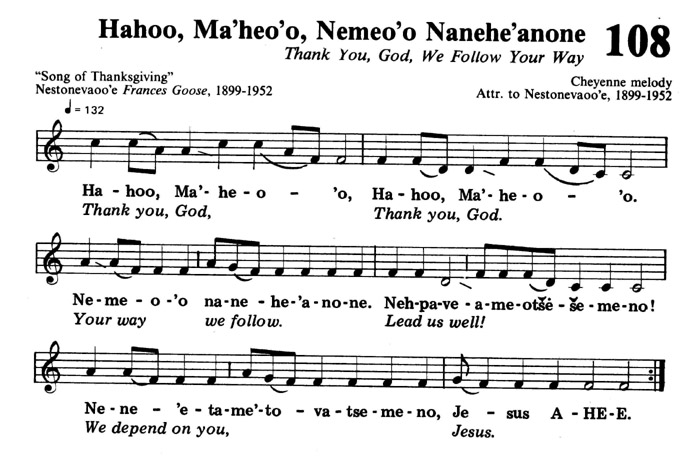

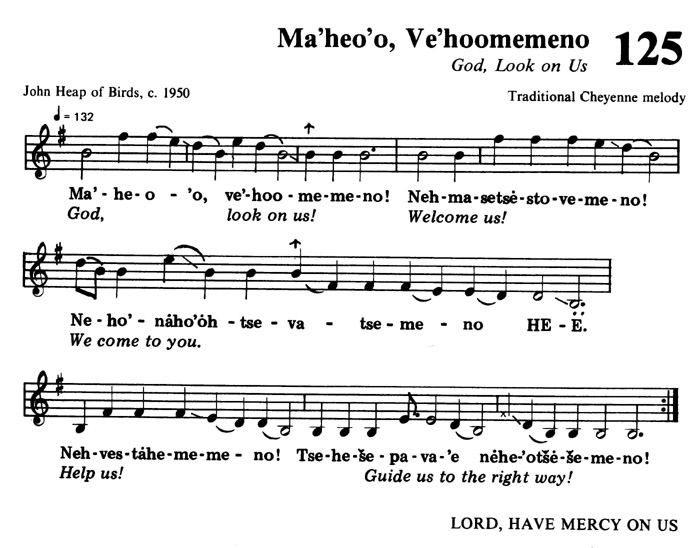

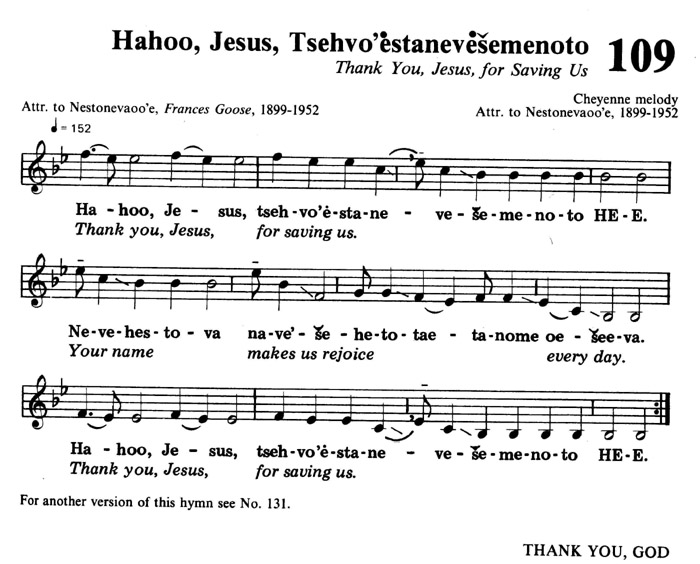

In keeping with the Spirit of the Creator, however, the emerging gift of indigenous hymns was not a mere imitation of European hymns, but rather the representation of something altogether new. Fortunately, whether intended consciously or not, Plains Indian Christians often failed to accurately imitate many essential musical qualities of European hymnody. Instead, their music is distinctly Native, but with a unique style and grammar to differentiate it from other genres within Native music. Markers such as the vocabulary and cadence of vocables (non-meaning syllables, see the "HE-EE" at the end of most songs), rhythm and pitch elements of melody all connect this new music with the new way of Jesus. Other genres (e.g., dance, lullaby, peyote, etc.), have different and distinct vocables, pitch, and rhythm markers in their own right. A Plains Indian musician can tell from portions of any song of his or her tribe the social or religious usage of that song. This tradition is unique, uniquely American, and worthy of respect and learning far beyond the environment of its origin.

Second, indigenous hymnody was private, according to the Plains Indian tradition regarding music. Songs are "received" (not composed) in private dreams or visions, and then privately "owned." Songs are sung privately for special gatherings and events. The tradition of Cheyenne hymns began in small meetings as Cheyenne singing preachers shared songs they had received.(7) With only a few exceptions, these songs were not incorporated by white missionaries into Sunday morning worship. Instead, songs were shared in private among extended families, particularly during times of bereavement. The songs became memorials, especially as elders who knew their days were few would pass on a song to a younger person, in the Plains Indian tradition of "giving" a song. This was primarily the setting that preserved the Cheyenne hymns into the 1970s.

Finally, many missionaries to Plains Indians discouraged the use of indigenous hymns in worship. To both missionaries and civil authorities this music represented a pagan influence, albeit with Christian words. The melody and meter were different from western music, and it was feared that the music itself would encourage the Indians back to their sinful ways. Rodolphe Petter, long-time missionary to the Northern Cheyenne, wrote a letter to the mission headquarters in Newton, Kansas, regretting the visit by Southern Cheyenne singing preacher Harvey White Shield, who was leading prayer meetings in Lame Deer and singing his Southern Cheyenne music, harming the mission effort by "watering down the Gospel."(8) Petter went to enormous work over several decades and editions to translate a large number of his favorite German and English hymns into Cheyenne to meet their musical needs in worship.(9)

Despite the obstacles, indigenous Christian hymns were recognized as a legitimate expression of Christian worship by some missionaries. Mennonite and Baptist missionaries to the Southern Cheyenne and Kiowa were not as hostile toward the development of indigenous hymnody.

J. B. Ediger, Mennonite missionary to the Southern Cheyenne in the 1930s, was one of few missionaries to the Cheyenne to affirm their indigenous hymnody. His daughters remember him starting to have the Cheyenne singers sing their hymns during Sunday worship. They remember that this was controversial with the sponsoring churches.

Mennonite missionary Malcolm Wenger and his wife Esther spoke with me soon after my first encounter with Cheyenne hymns at Birney, Montana, in 1973. They were long-time missionaries in Montana, considerably later than the Petters. Malcolm and Esther encouraged the indigenous hymn tradition in Montana as well as Oklahoma. They made a number of recordings on 1/4 inch tape, and did considerable writing of text. Their passion for this gift from the Creator was contagious to me, and we collaborated. They were aware of the decline in use of Cheyenne hymns in Oklahoma during the 1960s and 1970s. Malcolm was reflecting the concern of elders who knew the old "Cheyenne Gospel Songs". He first introduced me to Haalman Little Coyote in Seiling, Oklahoma the following year during a church conference, and helped me set up a recording session.

That was the beginning of the Cheyenne Hymns recording project. For the next several years I made more than a dozen trips to Oklahoma or to Montana to record people who explicitly wanted to contribute to the hymns project, to preserve the tradition for the younger generation. These were usually older people with a strong sense of mission. Sometimes elders arranged for younger persons, whom they had taught, to sing for the recording. The Cheyenne named on p. 195 of the hymnbook, in the handbook section, are the people who essentially made the Cheyenne hymnbook.

I spent little time deliberately promoting the hymnbook and the recording project. I simply went where I was asked to go to record someone who had hymns they wanted to contribute. Almost no money was exchanged; only informally for emergencies. Lawrence Hart, Southern Cheyenne traditional chief, and his wife Betty helped with making my appointments.

In Montana, Pastor Willis Busenitz did much of the organizational work and fund raising for publication. He arranged for Wycliffe missionary linguists, Wayne and Elena Leman, to come to Montana Cheyenne country. They saw the value of the hymns project and ended up doing the writing and syllabizing of the hymn texts. Their work, especially that with the Petter hymns, was essential.

When I was working in Oklahoma in the middle 1970s with a variety of elders who remembered the indigenous hymns, we had a "Mennonite Indian Leaders" conference in Clinton. An important item on the agenda for me was the Cheyenne hymnbook, and I presented several song pages from both the translated stream, produced by missionaries, and the indigenous stream, produced by the native converts. Afterwards, an argument developed between the Northern (missionary translated hymns) and Southern Cheyenne (indigenous), both unsure that the other really respected their own tradition. For a time the conversation was divisive. Unknown to me, the discussion continued late into the night at their place of lodging, and resulted in a miraculous gift of conflict resolution in a gifting ceremony between the Southern and Northern Cheyenne (Louise Fisher and Pastor Willis Busenitz remember this event).

The symbols on the cover of the hymnbook reflect this unity, and are especially meaningful to those who knew this conflict. The shield is the Northern Cheyenne symbol. The peace pipe is the Southern Cheyenne symbol. Their combination in one logo illustrates the unity found in the hymnbook. Petter's hymns and other translated hymns are interspersed with the indigenous hymns.(10)

While the primary goal of the Cheyenne Hymns project was to keep alive a valuable tradition, other goals were served as well. A second goal was the promotion of Cheyenne language use among Cheyenne. A third was to facilitate cultural awareness of both Cheyenne Christians and non-Cheyenne who shared with them in Christian ministry. Cheyenne hymns are used in Christian worship I think far beyond what would have happened without Tsese-Ma'heone-Nemeotótse.

I have a personal fourth goal, partially fulfilled. I believe the indigenous hymns tradition of the Cheyenne and Crow, as well as other ethnic groups, has equal validity to that of any other ethnic group, including the European. All the other American folk music has a European or African origin, and the style originates on other continents. The music of Native Americans is the only true indigenous American folk music.(11) So I believe this style of music and dance should be at home in the mainstream of American musical culture. This change is beginning to happen.(12)

One thousand copies of the Cheyenne Hymnbook were produced, in hardback. The cost of publishing--music typesetting, layout, printing, and binding--exceeded $30,000. I volunteered typesetting the Cheyenne text underlayment, with free use of a proportional typewriter at Faith and Life Press. I also wrote the essays and the handbook notes, and oversaw the publication. Actually, volunteering is not quite adequate. I received support from New Creation Fellowship Mennonite Church for myself and my family while doing the field work, rough drafts, checking, underlayment, etc., off and on from 1978 through 1982.

The initial reception in Montana was good. People started using the hymnbook from that time and use has continued, even increased. The discovery of genuine "Indian hymns" of many families in Oklahoma greatly complemented the hymns of Maude Fightingbear in Montana, the only Montana Cheyenne with a significant number of indigenous Cheyenne hymns prior to the Cheyenne Hymnbook Project.

In Oklahoma the oral tradition was the origin. Now, the hymnbook is used as a reminder of the songs sung long ago. But this in itself has problems. Oral history is based on remembering personal relationships through stories, rather than pure events. Once something is written down, the paper is the source of remembering rather than a human relationship.

Songs were and still are possessed by individuals and families, regardless of the identity of the first singer. Family relationships properly determine whether and how a song is sung. When it's written on paper, relationships are devalued, and respect diminishes. This became more problematic as I found variants of hymns in different districts, both of which were claimed to be exactly like the original. I learned not to challenge these differences, just to let the variants be. Some I handled with footnotes, others with more significant changes I wrote out as separate hymns. I have come to deeply respect the validity of concerns for the negative impact of writing down an oral tradition.

Another concern, emphasized by anthropologists, is that writing down an oral tradition will irrevocably alter and possible destroy the original art form. This is still a concern. However, I was impressed that at the time the project began most of the newest hymns were decades old. The project itself encouraged at least one Cheyenne Christian to orally arrange a family song for inclusion in the hymnbook.(13)

The current work among Christians of the Crow Nation of Montana has encouraged new hymns, and the tradition seems revitalized by the choice of the Crow and the Cheyenne to use paper for preservation rather than depending totally on the oral tradition(13).(14)

Petter translated about a hundred hymns into Cheyenne from his own Swiss/English tradition to meet his musical needs for worship among the Cheyenne, in their verbal language. He did not accept their musical language. This music lacked the uniquely original American pitch inflection and rhythmic elements children of European immigrants still find incomprehensible or simply accidental in the music grammar that has existed on this continent for thousands of years. In compensation, the harmony and accompaniment by the piano represented a powerful new musical grammar for the American Plains nations. They accepted the cross-cultural musical challenge. Such a challenge was not reciprocated, except in the verbal Cheyenne language, at least for purposes of Christian worship.

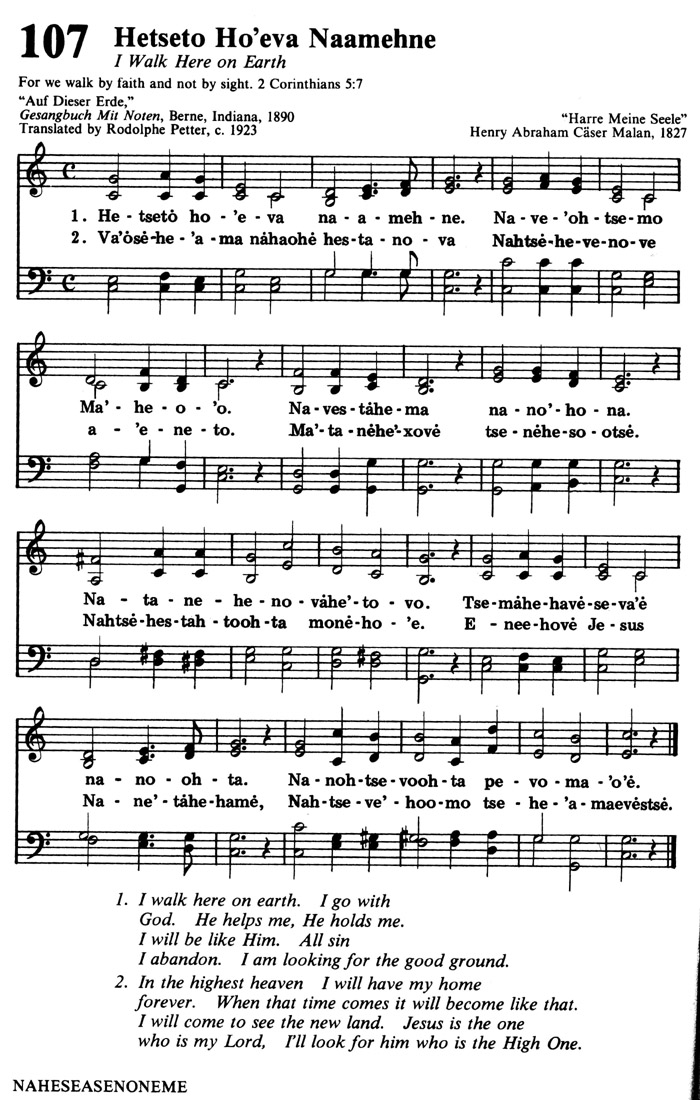

This particular German hymn was published by Mennonites in the 1890 edition of "Gesangbuch mit Noten." See the additional information with the hymn header.

For a decade or more beginning in the 1980s, Emma Hart, Alberta Zotigh, and Nelly Jones blended their voices in traditional Cheyenne harmony at countless memorial services, wakes, and other Christian worship occasions. This hymn was written from their recording made at the Koinonia church in Clinton, Oklahoma, in the early 1980s. Notice the vocal bends, pitches out of tune, and irregular rhythmic expressions related to Cheyenne language. The actual grammatical analysis of this music would separate truly significant musical sounds from the irrelevant within the culture. Only linguists do this for languages, and ethnomusicologists for ethnic music. This element is what makes music no more a universal language than is English or Chinese. In fact, there are many languages of music, each with its cliché elements of sound incomprehensible to anyone outside the tradition. Yet human ears pick up all the data. It’s the human mind that filters the significant from the irrelevant, from cultural learning of sounds beginning even before birth.

In this song, the institution of Italian notation breaks down, because Italian notation is based on European musical grammar. So the unusual elements in the notation represent only a portion of the musical sounds in the memory of a Cheyenne musician. Even with tools of ethnomusicology used in writing, only hearing the music over and over with guidance from a musician allows comprehension of some of these significant sounds. It is remarkable that this is easier for children, who don’t need cognitive awareness to understand and employ the elements musically.

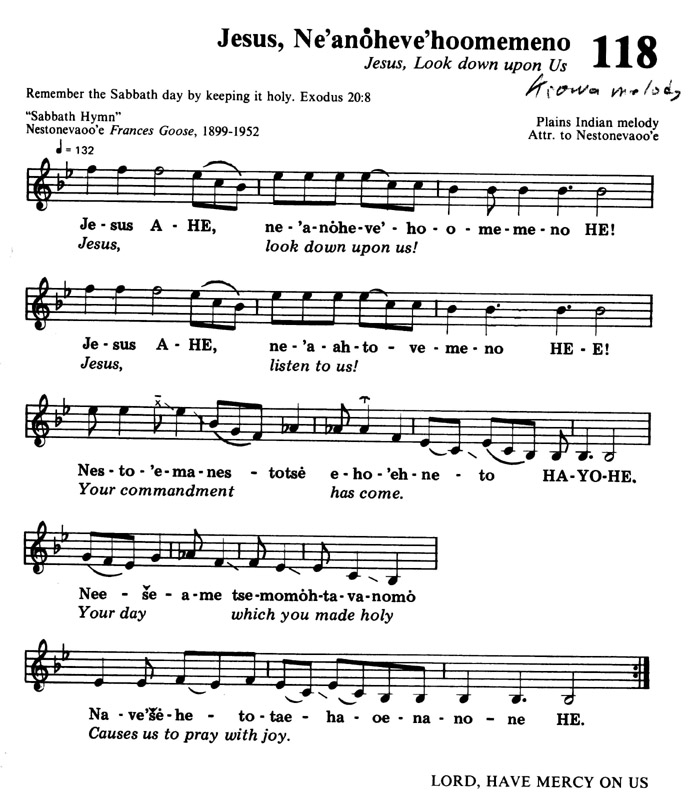

Many of the Cheyenne musicians who received songs for Christian worship from Ma’heo’o (Creator God) worked to adapt their music to the restrictions of new European standards for music. They had varying degrees of success. This hymn was one of the cross-cultural hymns selected by the hymnal committee of the Mennonite Church for inclusion in "Hymnal: A Worship Book" published in 1992. While it is a genuine ethnic Native American Hymn, it is also something of a hybrid. The elements of vocal inflection, scale intonation and rhythm are largely stripped away in favor of an Asian-style tuned pentatonic scale, making it compatible with European musical grammar. So this tune, lacking many clichés of the American Plains nations, adapts well to less obtrusive harmony from the European tradition, such as canon, augmentation, or duets. It can even be accompanied (carefully) on guitar or piano.

This hymn tune appears to have little European influence. The frequent inflection, low rhythmic continuity, and irregular phrasing are more closely tied to speech patterns, like traditional songs for children often sung without a drum. Here, Italian musical notation is especially inadequate Yet the artistic integrity is unmistakable.

One of Bertha Little Coyote’s favorite hymns. Mrs. Little Coyote was from Seiling.

1. Tsese-Ma'heone-Nemeotótse: Cheyenne spiritual songs. (Newton, Kans. : Faith and Life Press, 1982).

2. The early Crow hymn was sung by Max Big Man and recorded by Lowie in the 1920s. A cassette copy of the wax cylinder recording is available from the Lowie museum in California. Lowie's recorded sound track is included with recordings of the first Crow hymnbook, Chiwakiiwalaxuua: Crow spiritual hymns ( Lodge Grass, Mont. : Crow Indian Baptist Association, 1991, c1990).

3. Sara Heap of Birds Bent explains the origin of a Cheyenne hymn as inspired by hearing the European church sounds (Tsese-Ma'heone-Nemeotótse, p. 156, handbook entry for hymn #3). I also have never observed, in indigenous hymns, the common Northern Plains drum beat patterns I call metrical layering with the voice, called "syncopation" by some ethnomusicologists. Christian hymns are definitely bent toward the European understandings of phrase length, meter, voice pulse and scalar structure of melodies. I was fascinated with a "Crow hop" beat employed with a tambourine accompanying a fast Crow hymn with vocal pulsations alternating in a complex pattern of twos and threes. Listening to the recording, my source commented, "That beat doesn't fit well with Christian worship." I asked why. He said, "For Christian worship, the tambourine and the voice (pulse) need to be together, unified," illustrating his belief that a Christian song should fit a more European-sounding rhythm.

4. Sara Bent, of Clinton, Oklahoma, one of my sources for the Cheyenne hymnbook, said that her uncle, Alfrich Heap of Birds, one of the first Cheyenne Christians, was instructed by an early missionary on the text of his indigenous songs. I remember her telling me that the missionary wrote the texts of the hymns for him. I'm still not sure why she so emphasized to me that the missionary endorsed the validity of Heap of Birds' hymns. Sara Bent's comments that the missionary actually wrote the texts to the indigenous hymns were possibly meant to legitimize her brother's and her uncle's hymns, as a means of helping "us poor Indians" accept the Gospel. In fact she used that phrase frequently with me. Sara was apologetic at times about how they sounded so "Indian." She also was aware of the story of Rodolphe Petter who had help from Cheyenne Christians in Montana, and his hymns did not sound Indian. Yet she agreed with the Northern Cheyenne women that these were also "Indian hymns." Sara sang Cheyenne hymns of both European and Cheyenne musical traditions as a child into adulthood, and was personally concerned with the conflict between the Southern and Northern Cheyenne over the hymnbook publication.

5. Some of the hymns written with an indigenous hymns format had a familiar ring to my ears from my childhood. They did not follow the usual pattern of Plains Indian music with descending intervals through about an 8ve and a 4th or 5th. I have identified the original European tune in all but one of these. The clue is in the upper right corner of a one-line melody hymn tune, where I have written, "based on _______". An example is Harry Starr's hymn, no. 22. Harry himself told me this hymn was from an English hymn, and only the text is indigenous. Others are 2, 3, 24, 40 (I was a long time finding "Stars in my Crown", which I remembered my Grandmother singing), 46, possibly 51 (I can't identify the English hymn), 52, 59 (just a hunch), 76, 104, 123, 152, and 154. These 14 hymns are all the "Cheyenne-ized" European hymns I found. You will notice from the dates that most are recent.

6. The current college text Music and Dance of the Crow (Dale Old Horn, 1999), totally ignores the Christian indigenous hymnody of the Crow tribe. One prominent ethnomusicologist was unaware of indigenous Christian hymnody among Plains people when I introduced the Cheyenne hymnbook to him.

7. Cheyenne Christians who received songs early on include Harvey Whiteshield, Mrs. Belle Rouse, John Heap of Birds, Mrs. Frances Goose, Alfrich Heap of Birds and others.

8. I found correspondence to this effect in the Petter collection (MS.31) at the Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas. Harvey Whiteshield's songs are also in the 1982 edition of the Cheyenne hymnbook.

9. Part of my job with the Cheyenne hymnbook project was to research the named tunes to Petter's translated hymn texts. The 1982 Cheyenne Hymnbook, Tsese-Ma'heone-Nemeotótse, has all his translated hymns with music. None have Native American musical influence.

10. The format clarifies the difference between translated and indigenous hymns in the hymnbook. The translated hymns are mostly in four-part harmony, written with a keyboard accompanist or part-singers in mind. I have treated the indigenous hymns in the layout equally, but differently. Notice there is only a melody. There are no time signatures, unless the song clearly was metrical. Different lengths of the score represent the different lengths of phrases, which then give a visual impression of the Plains Indian song form, for which phrase length and poetic meter is not confined to a mathematical formula as in European music. On page 196 of the Cheyenne hymnbook I have written an essay on transcription problems with the indigenous hymns, reflecting some of these concerns.

11. I spent several years in Busby, Montana, as a school music teacher, and I made a point of I learning to sing at the drum at social gatherings. I became a willing but slow student of Cheyenne social dance music. I was slow because I had to write the tune and syllables of songs to remember them, to the endless humor of my fellow musicians. During this time, it occurred to me that the music I was learning was among the only true indigenous American folk music.

12. In the last decade or two, Native American music has emerged as a genre of popular music, complete with categories in the Grammy awards and in the typical large retail music stores across the nation. This has stimulated cultural preservationists to help young musicians in the Crow tribe to understand and appreciate their own rich heritage of celebration arts. I am currently instructor for a course at Little Big Horn College: "Music and Dance of the Crow" CS134. Of course, my role is that of a facilitator rather than a primary resource for the information being studied.

13. Gladys Old Mouse was helping Wayne Leman (with Wycliffe) translate a portion of John's gospel chapter 3, when she was inspired to connect with a traditional Cheyenne giveaway song based on a Sioux melody. This hymn incorporates the Father's gift of the Son Jesus into the traditional value of generosity expressed in the original text. For further information see the Cheyenne hymnbook #84, and the handbook entry.

14. Two books and accompanying recordings are available at Crow Hymns Project, Box 397, Crow Agency, MT 59022, or call the Crow Hymns Project at the Crow Agency Chamber of Commerce, ask for Joe Bear Cloud, (406) 638-7272. The Crow Hymns Project is currently considering publishing all the hymns in an open hymnbook to which new hymns can be more conveniently added.