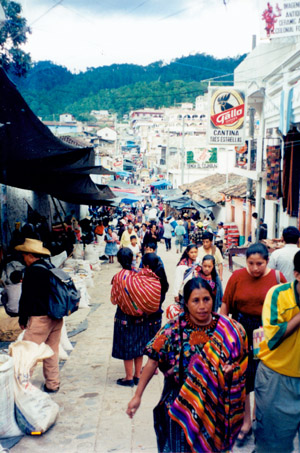

Guatemalan indigenous population in

Chichicatenango who were heavily impacted by the civil war

March 2005

vol. 60 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2005

vol. 60 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Julie Hart, PhD, has been a professor of Sociology and Peace Studies at Bethel College in Newton, Kansas since 1994. She received her M.A. in International Peace Studies in 1991 and PhD in Sociology from the University of Notre Dame in 1995. During the summer months Julie serves as a reservist with Christian Peacemaker Teams in Israel/Palestine (1997-2000) and in Colombia (2004-5). She recently returned from a two-year sabbatical in Guatemala City with Mennonite Central Committee where she was writing a series of six peace and justice texts to be used in the REDPAZ peacemaker formation program throughout Central America.

Guatemala was my home from 2001-2003 during my sabbatical from Bethel College. While there, I had direct exposure to three models of peacebuilding and reconciliation post civil war. I worked for Mennonite Central Committee who provides funding and staffing for one of the projects. All three models are excellent examples of theory in practice--something hard to find. In addition, Guatemalan Mennonites were involved in all three models. They held lead roles in two of the programs and participated actively in the third. Before sharing specifics about these models, it is important to understand the Guatemalan context and some peacebuilding theory that offers a backdrop for this work.

The year 1996 marked the end of the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War. This was a fairly typical Cold War conflict between rural peasants seeking land reform and a voice in the political arena and a series of military dictatorships supported by the US government in their efforts to stamp out communism. The government utilized a variety of tactics to divide and conquer rebel groups. By the 1980s government violence had escalated to include a "scorched earth policy" that ordered Guatemalan soldiers to enter rural Mayan villages thought to be aiding communist rebels and destroy them. Homes were burned, animals scattered, crops destroyed, and people killed or maimed. Both the Catholic Church's and the UN post war investigations labeled these actions genocide. The reports suggest that 200,000 persons were killed and nearly a million became refugees. All this in a country of only 12 million people.

Guatemalan indigenous population in

Chichicatenango who were heavily impacted by the civil war

This civil war in Guatemala was occurring simultaneously with civil wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua. The rebel groups in each society were fighting for equal opportunities for the masses of peasants who suffered from malnutrition, unemployment, lack of land for self-sufficiency, illiteracy, and little voice in the political arena. By the late 1980s, these wars had attracted the attention of the world and Central American leaders gathered to bring some resolution to the conflicts. Cease-fires and peace accords were reached in most countries by the late 80s and 90s. Social science theory suggests that post cease-fire is when the real work of sustainable peacebuilding and reconciliation begins.

According to Adam Curle and John Paul Lederach, the process of building a sustainable peace post cease-fire involves a variety of strategies. Lederach suggests that most importantly, the process of sustainable peace is about rebuilding broken relationships. This is accomplished through a combination of truth telling, forgiveness, justice or restitution, and a vision of a shalom community. First, a forum for truth telling is needed for perpetrators of violence to admit their wrong-doing and victims to share their trauma. This often occurs through official truth commissions where both victims and perpetrators are given an opportunity to share, have their reality legitimized, and to begin a process of healing. Second, mercy in the form of forgiveness for wrong-doing is necessary for the perpetrators and victims of the violence to move on in their lives. This often occurs in some type of amnesty program. Third, justice requires that restitution, financial or other, is offered to those who have suffered. Some governments offer payments to help cover the cost of loss of life, limb, property, or mental anguish for victims of genocide and war. Finally, sustainable peace requires a process of envisioning a new future together and at peace for former combatants. Conflict transformation processes and structures must be built to support the people in building toward this vision.

1996 Peace Accords sculpture in Guatemala City; rose in center is

replaced each day. Phil and Julie Hart seated at left.

Lederach suggests a 20-year time line for sustainable peacebuilding. This begins with the cease-fire and is followed by crisis intervention in the first years post-conflict. Refugees must be fed and sheltered while infrastructure is rebuilt. When there is some level of societal stability, former enemy leaders are brought together at the grassroots level in intensive workshops to envision a society at peace with justice for all. Participants are encouraged to think systemically about structures that could facilitate constructive conflict transformation in the future and provide equal access for all groups to the rights and resources within the society. Third, these grassroots leaders should attempt to identify the root causes of the recent conflict and explore ways to reduce these problems as a way to prevent future conflicts. Once the envisioning process is complete, these groups should design structures and processes to bridge the gap between the desired future and the present. Finally, trainings in conflict transformation, prejudice reduction, trauma healing, small group facilitation, and problem-solving should help grassroots leaders realize their dreams for a more just future. These would be offered within three to five years post conflict. In light of these recommendations, we will now examine three models of grassroots peacebuilding post conflict in present day Guatemala.

Rural border town between Guatemala and Honduras, 2003

Following the Guatemalan Catholic Church's investigation and report of the war's violence in the REMHI Report (Recuperation of Historical Memory), the church has responded with a Trauma Healing Project to address the ongoing needs of thousands of war victims. Following the gathering of war stories, the Catholic Church sent seven teams of professionals to provide rehabilitation for victims of torture and organized violence. The professionals organized self-help groups and trained lay leaders to continue these groups long-term.

The groups were formed in the seven Guatemalan dioceses most affected by the war. Groups covered a variety of needs including reflection, self-help, and exhumation. In addition, individual counseling was/is offered for those severely affected by post traumatic stress syndrome. The professional teams trained local volunteers willing to serve as mental health promoters in their villages on an ongoing basis. According to a 2003 evaluation of the project, 344 self-help or reflection groups were formed reaching 10,680 persons over a period of four years. In addition, 21 groups formed around a desire to exhume mass graves, identify dead relatives, and provide a proper burial. This involved another 450 persons. The work of both types of groups was led by 425 volunteer mental health promoters using a mental health guide developed in the area hardest hit by the war. Each diocese was encouraged to individualize the guides to address the cultural differences of each of the 22 Mayan language groups present in Guatemala.

The techniques for trauma healing varied widely and were geared to particular symptoms. Common symptoms of the victims included depression, paralyzing fear, extreme anxiety, headaches, heart palpitations, debilitating fatigue, lack of appetite, difficulty breathing, family violence, and alcoholism. The professional mental health providers used such therapies as acupressure, natural or herbal medicines, and various forms of talk therapy in individual sessions for those with acute problems. The volunteer mental health promoters used talk therapy and peer support as tools in the various types of self-help groups. These groups were no larger than 20 and met over periods of months or years. Some groups discussed the REMHI report in its popular adaptation to educate people about the extent of the damage from the war.

The use of non-professional facilitators for self-help groups in trauma healing work had significant advantages for Guatemala. In many cases the option was use of non-professionals or nothing at all. The Mayan people tend to be more open to individuals within their communities and language groups than with highly trained outsiders and thus this approach was able to reach a wider spectrum of the population. Using the support group approach enabled more persons to be trained in this technique, persons who could continue the groups indefinitely without dependence on outside funding. Even if no "professional therapy" took place in the groups, the process of sharing one's story, hearing that one's symptoms are common among survivors of trauma, and realizing that one is not alone in the journey are beneficial.

The REMHI project provided for much of the truth telling that is needed post conflict. This was followed by opportunities to heal the lasting impacts of war on individuals and families. The primary weakness of the project appears to be that it has only reached about 10,000 survivors. If 200,000 died in the genocide and nearly a million were displaced, certainly more than 10,000 were affected socially, economically, and psychologically by the war. Thus, the program is not reaching all of the people that might benefit from it.

Shortly after the Guatemalan Peace Accords were signed in 1996, Mennonite church leaders throughout Central America gathered to discuss how their peace church tradition might support the efforts of the Guatemalan, Nicaraguan, and El Salvadoran peace accords. This group, with funding from Mennonite Central Committee and some European NGOs, formed the REDPAZ to provide peace and justice education, healing post civil war, and a supportive network for peacemakers throughout Central America.

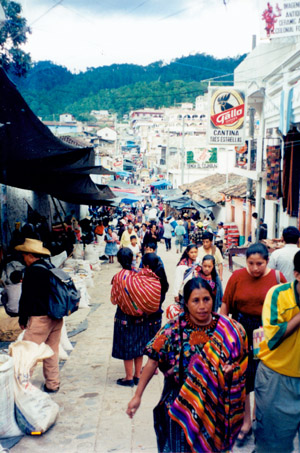

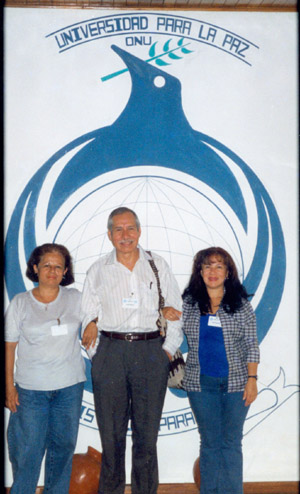

REDPAZ students meeting at UN University of Peace in Costa Rica, 2003

The peacebuilding model they adopted involves a series of ten 5-day courses held in retreat formats over a two and one half-year cycle. The courses include social science theory and practice as well as biblical perspectives. I was responsible for writing six of these texts and consulting on the others. The courses include the following topics and are offered in this order:

Students apply for a place in the program and, if chosen, scholarships are available to cover the costs of tuition, room, board, and reading materials. The series of texts or manuals have been designed and written for the Central American context. The texts include reflection and homework questions as well as an anthology of additional readings. Instructors are chosen for each course based on their experience with "popular education" and their familiarity with the topic.

REDPAZ staff, Guatemala City, 2003. Jose Luis

Assurdia, Daagya Dick, Lourdes Perez, Julie Hart.

Each course draws the same group of 50 students together at two different Central American locations to study, discuss, and learn together. The retreat setting and popular education format encourage students to build relationships that will reach beyond the class. The students worship, pray, sing, and relax together in the evenings. E-mail lists maintain contact during the three months between each course. Students receive new peace-related information and are notified of needs and prayer concerns within the group during this time. Once a year, alumni, current students, and peace organization representatives who are members of the REDPAZ gather to explore a current issue such as economic globalization and vote on the direction and policies for the group. The students and members of the REDPAZ are expected to share what they learn in the courses and annual meetings in their local organizations and churches. They are given teachers manuals to help with providing creative delivery of the materials.

REDPAZ students, Guatemala City, March 2003. Julie Hart in center in

shawl.

One of the challenges of the program is that most students are self-employed in farming or in the private sector and must have the economic freedom to attend four week-long courses per year. Students join with a variety of educational backgrounds. Some have only an eighth grade education while others hold masters degrees. The reading materials and homework assignments are geared to an introductory college level and thus some students find them very challenging.

The program has reached approximately 150 students thus far and continues to explore funding to widen its reach. Each year persons outside of the Mennonite Church working with non-profit organizations are seeking peace education and approach REDPAZ to participate. Currently about one third of the students are from organizations or churches other than Mennonite. This program thus provides many of the skills and knowledges needed to heal, deal with conflict, and envision a more just society.

Following the 1996 Peace Accords, the UN and OAS formed a Consultative Group for Guatemala to monitor the application of the accords and assist as necessary. Beginning in 2002, the consultative group began six inter-sectoral dialogues among civil society and governmental leaders. The six areas include: Culture of Peace and Reconciliation; Rural Development; Modernizing the Armed Forces; Rights and Identity of Indigenous People; Citizen Rights and Security; and Economic Development.

I was able to participate in the first group that met from August of 2002 through August of 2003 to discuss building a culture of peace and reconciliation in Guatemala. Nearly 200 persons were invited to participate in 3-hour weekly meetings throughout the year. These participants came from all church denominations, all indigenous groups, police, army officials, business, education, agricultural and health sectors, the courts, universities, artisan groups, political parties, human rights organizations, women's organizations, and labor. Participants tended to be consistent throughout the year although participation declined over time.

Each week, small groups of no more than 20 were presented with a new question or topic to discuss. For example, What are the components of a culture of violence? Small groups would later send an elected representative to monthly joint sessions to iron out a consensus statement. The consensus statements were then reviewed by each small group for changes. The final statements were to be made public. Later in the process, each group was asked to discuss and suggest concrete activities that might be implemented to build a culture of peace in Guatemala based on previous work. The groups grappled with such issues as ways to build trust between citizens and the government. They reviewed the peace accords and evaluated implementation while making suggestions for improvement.

The beauty of these small groups is that they brought together individuals who would not normally dialogue, especially persons who had opposed each other during the war. They were asked to work together to envision their society five, ten, and twenty years into the future. In the process, they learned to listen to diverse perspectives and to reduce animosities as they worked on a common project important to them all. This process was supported by well-trained group leaders with ample resources and skills to facilitate the process. Every two months the group gathered for a plenary session with various experts on topics such as progress on the peace accords.

While the Guatemalan government has shown little interest in the Peace Accords or peacebuilding post conflict, civil society and inter-governmental programs are proceeding with programs that many academics and practitioners suggest should build a sustainable peace.

First, and ideally, those who have been traumatized by a war must share their trauma and discover some level of forgiveness, receive restitution, and experience some form of reconciliation with those responsible for their trauma. In Guatemala, this process was begun by the Catholic Church in their REMHI project to reconstruct stories from the war--a process of truth telling. But to leave it at truth-telling is inadequate as forgiveness and reconciliation often require a chance to talk with those who have committed harm and are repentant. Although Guatemala is not providing direct reconciliation between offender and victims, the work of the Catholic Church is a positive step toward healing the wounds of the war among a rural, largely illiterate, and heterogeneous population through their Trauma Healing efforts.

In addition to trauma healing, Lederach stresses the need for conflict transformation training to prevent future conflicts. People need to understand their situations, rights, and responsibilities and hold concrete skills to act on this knowledge. The REDPAZ is an excellent model for providing this kind of education with the potential to spread to groups and congregations throughout the society. In addition, the REDPAZ project is helping to build networks of people who identify with the role of peacemaker and may serve as resources when future problems arise. The networks are also empowering change agents to address some of the root causes of the civil wars such as human rights abuses and lack of access to political power. The only limitation of this program is the small number of participants it is able to reach each year.

Finally, Curle and Lederach suggest that the road to sustainable peace and reconciliation be in a process of visualizing the future with those from a variety of sectors. This is the work of the OAS and the UN dialogue groups. The fact that they place former guerillas and army officers side-by-side to explore concrete strategies for building a culture of peace is vital to altering conditions that could lead once again to war. These diverse groups begin to listen to and trust each other in small ways. Over a year long period, they will hopefully form new relationships that will stand the test of time. They might also begin to understand how "the other" thinks about a healthy society and find common ground. It is in areas of common ground that they can combine their energies and constituencies to elect supportive politicians and press for societal change.

Although each of these groups is only reaching a fraction of the necessary population, and there is no coordinating body, it was gratifying to be a part of efforts that were, based on experience and theory, truly addressing the peacebuilding needs of a post civil war society.