Part of 1665 Vissher map of New World showing Swanendael and Hoere Kill(lower left)

March 2005

vol. 60 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2005

vol. 60 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Leland Harder is living in active retirement in North Newton, Kansas. He taught for twenty-five years at Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Indiana. As a sociologist he extensively gathered and interpreted data about Mennonite church membership. In retirement he has worked on numerous family reunion and genealogy projects.

Irvin Horst and I should have argued with Harold Bender when he published our articles about Pieter Cornelis Plockhoy in the July 1949 issue of Mennonite Quarterly Review.(1) In his editorial he wrote, "It is doubtful whether Pieter Plockhoy has any meaning at all for Mennonite history." Then he wrote that "the colony which he established in 1663 in Delaware was in no sense a Mennonite colony even if some of the colonists were Mennonites, and in any case it lasted but two short years." And again, "Plockhoy may have some significance in the history of social and political thought… but his ideas themselves derive from other sources than his Mennonite background." Bender was wrong on all counts. He tried to compliment us when he wrote that our "scholarly papers exhaust the subject and tell the whole story of Plockhoy so far as it can be told." Wrong again. It is time for a little updating.

On July 28, 1663, the Dutch ship St. Jacob dropped anchor at the mouth of the Delaware River in colonial America, and forty-one Dutch Mennonites were put ashore with "all kinds of necessaries and small articles for their own use, as for agricultural purposes, etc."(2) Their leader was Pieter Cornelis Plockhoy. They disembarked at a place called "Horekill," also called "Zwaanendael" (Dutch for "valley of swans").

Part of 1665 Vissher map of New World showing Swanendael and Hoere Kill(lower left)

This was the first aggregate of Mennonites to come to America as a group, although there were a few prior references to individual "Mennonists" or "Menists" or "Anabaptists" who had arrived from the Netherlands. In fact, several Mennonists were meeting on Long Island occasionally, and it was said of them that "for the most part, they reject infant baptism, the institution of the sabbath, and the office of preacher altogether , saying that 'through clerics come all sorts of contention into the world.' Whenever they meet together, one or another reads something for them."(3) These references to anti-pedobaptism and anti-clericalism were typically Anabaptist, although the more immediate source for these attitudes was the so-called Collegiant movement with its center in the Mennonite Church of the Lamb in Amsterdam, known today as the Singelkirk. This was the congregation from which Plockhoy and some or all of his group came to Delaware.

I was an undergraduate student at Bethel College 57 years ago when I first became interested in Plockhoy's witness to the Christian world. In search for a subject for the assigned term paper in a Mennonite History class taught by Cornelius Krahn, I read C. Henry Smith's book, The Mennonites of America,(4) and was captivated by the chapter entitled "Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy and the Mennonite Colony on the Delaware." Smith's book was published in 1909, and I suspected that there was more to be discovered about this fascinating 17th century reformer.

Smith's chapter provided a good beginning: "The first [Mennonite] settlement in America of which we have anything like definite knowledge is that made by Plockhoy and his small colony at the Horekill in what is now southwestern Delaware. Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy of Zierik Zee was a liberal-minded Dutch… social reformer of his day. He was of Mennonite descent and was perhaps himself a member of one of the several sects of that faith. Of his early life we know little, but by 1658 we find him in London addressing a letter to Cromwell in which he laid before the Lord Protector a scheme for the social and political reorganization of English society."(5)

I began my research by writing a dozen letters of inquiry to various libraries and historical societies in Delaware, New York, and Pennsylvania, the British Museum in London, and the city libraries of Amsterdam and Zierikzee. Bits and pieces of new information were received, and I obtained microfilmed copies of Plockhoy's four published writings--two in English and two in Dutch.

The term paper was expanded into an M.A. thesis at Michigan State University(6), and the first of several articles on the subject was published in Delaware History(7) and reprinted in the Mennonite Quarterly Review(8) along with an interpretive essay by Irvin Horst.(9) In 1952 Krahn published my work in book form as Volume 2 in the new Mennonite Historical Series.(10) My brother Marvin added an interpretive chapters about pamphleteering in 17th century London.

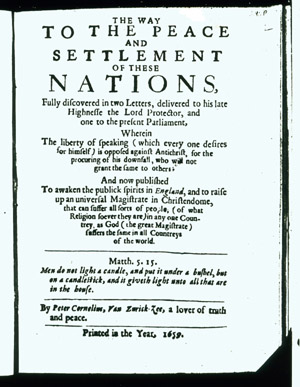

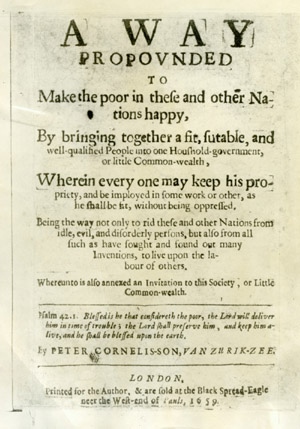

Plockhoy's reform efforts in England were short-circuited by the sudden death of Cromwell, but the titles of his two published tracts tell us much about his concerns: The Way to the Peace and Settlement of these Nations, fully discovered… wherein the Liberty of Speaking (which everyone desires for himself) is opposed by Antichrist…) and A Way Propounded to Make the Poor in these and other Nations Happy by bringing together a fit, suitable, and well-qualified People into one Household-Government or little Commonwealth.

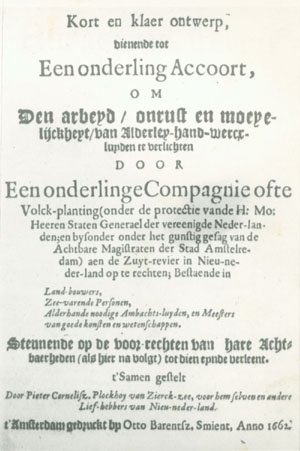

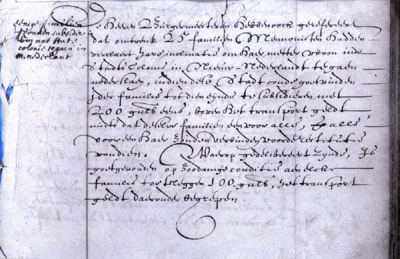

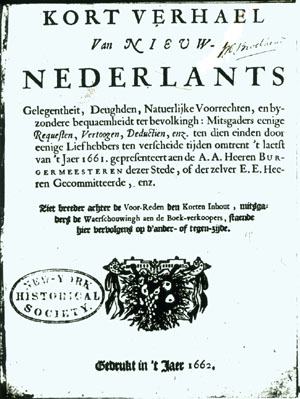

Back in Holland in 1662, Plockhoy secured a contract from the Amsterdam Burgomasters to establish his socialist community on the Delaware River in New Netherland (then called the South River) "with about 25 Mennonist families who have declared their inclination to remove to and reside in the city's colony in New Netherland."(11) Plockhoy had hoped to have a community of at least 100 adults, and in order to recruit additional settlers he wrote and published the first of two Dutch pamphlets, Kort en klaer ontwerp… ("Brief and Concise Plan intended to be a mutual Agreement for some Colonists willing to go to the South River in New Netherland"). Since Plockhoy's first concern was to help impoverished people, he may have recruited a few additional members from among the urban poor of Amsterdam.

Amsterdam council resolution concerning Plockhoy and his 25 Mennonite settler families

In any case, the group sailed on the St. Jacob and disembarked at the Horekil (now Lewes, Delaware) on July 28, 1663. They set up their hamlet, but barely thirteen months later the Dutch lost New Netherland to the British, and in the name of the Duke of York, who subsequently succeeded to the British throne, Sir Robert Carr and his soldiers "destroyed the quaking society of Plockhoy to a naile,"(12) as one eyewitness put it. That was almost all we knew about what happened to the members of the Plockhoy settlement.

The story was intriguing enough to prompt speculation. On Tuesday evening, May 27th, 1952, we turned on our radio to the local ABC affiliate station. It was the Cavalcade of America program sponsored by the DuPont Company in Wilmington, Delaware. The drama was entitled "The Valley of the Swans,"(13) starring Dana Andrews as Plockhoy and Louise Albritton as his wife.

CARR: In the name of his royal highness, James, Duke of York, I require of you and your company submission by virtue of the commission I hold in my possession.

PLOCKHOY: What is it you want of us?

CARR: This settlement is to be evacuated and burned to the ground in 24 hours. (SOUND; REACTION OF PEOPLE).

PLOCKHOY: Evacuated! Burned! Why?

CARR: All this is very distressing to me, Plockhoy. I… I hope you won't make it more difficult by arguing.

PLOCKHOY: Do you expect us to leave our homes on a moment's notice and not protest?

CARR: You've got to understand the realities of the situation. I haven't enough troops to garrison this place and New Amstel too… and my orders state that I cannot leave any settlement without protection from the Indians.

PLOCKHOY: But the Indians are our friends.

CARR: You can't depend upon the friendship of Indians.

PLOCKHOY: What then can we depend upon… the good offices of a government that has in mind the destruction of everything we've done since we arrived in America? Our settlement has prospered, sir.… We've accomplished much. Come and see our little village… the school house… the mill… the farmland that each man owns as his neighbor's equal.

CARR: Believe me, Plockhoy… this is a matter of colonial policy. I cannot leave you here without soldiers for protection, and I have no soldiers to spare. I'm sorry… sincerely sorry. Let me take you all to New Amstel.

PLOCKHOY: And if we prefer not to go there?

CARR: You can't stay here. It's either New Amstel… or…

PLOCKHOY: Or the wilderness?

CARR: Yes.

As the dramatized community consults about the decision they face, Plockhoy says, "Katherine and I have talked about it. We feel together on this. We have come so far in our seeking for freedom that we can't turn back upon the road. Safety is not half so important to us as liberty. And we believe liberty lies beyond the sand dunes… in the vast heart of this country. Deep in the forest, in some other valley, we will find a place to rebuild." The drama ends with Plockhoy leading his people out into the forest beyond the sand dunes.

But that's not really what happened. Fifty years ago I knew little more about what really happened, except for three tantalizing details. In the university library at East Lansing, Michigan, I found two old source books entitled Some Records of Sussex County, Delaware(14) and Original Land Titles in Delaware Commonly Known as the Duke of York Records, 1646-1679.(15) The former source revealed that on January 9th, 1682, a "Cornelis Plockhoy" received a grant of a "Towne Lott" provided that he build a house thereon within a year and that on May 28th, this Plockhoy and seven other men declared allegiance to England and became British citizens. The latter source listed the land titles of the seven men identified in the naturalization ceremony. At the time of these discoveries, I had no way to prove that any or all of these persons had been members of Plockhoy's group, although I suspected that to be the case.

The third piece of information was the Germantown [Pennsylvania] Rathbuch, written in German script and preserved in the library of the Pennsylvania State Historical Society. It was cited in C. Henry Smith's chapter as follows:

One day in 1694 Plockhoy, now grown old and blind, accompanied by his wife, evidently friendless and penniless, having heard somehow of the later and more fortunate settlement made in the meantime at Germantown, and coming, we know not whence, wandered into the village, where he met a hearty welcome. The court appointed [pastor] William Rittenhouse and John Doeden to select a suitable home in the village and provide for the needs of the aged couple. And here with his wife, Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy, the dreamer and social reformer, and so far as known, the only survivor in America of the ill-fated colony he tried to establish, after a long life of disappointments and vicissitudes, finally ended his days in peace among his brethren and countrymen.(16)

Germantown Rathbuch reference to Plockhoy

This interpretation of the Germantown document is interesting but again not entirely factual, as a more recently rediscovered source reveals. I refer to a 1671 census of inhabitants along the Delaware River first published in 1877.(17) Until 1977, it was unknown to Delaware historians because it had been appended to an unrelated document in the New York State Archives. Peter Stebbins Craig, a retired Washington lawyer and Fellow of the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, obtained the census and spent ten years painstakingly identifying the 165 heads of households that it listed. The territory from New Castle south to the mouth of the Delaware (now Lewes), a distance of eighty miles, was mostly wilderness in 1671; but the census included a listing of the 11 heads of households living at the Horekil (Lewes)--most of them apparently survivors of the Plockhoy settlement.

The original handwritten census comprising a two-page manuscript does not list Peter Cornelis Plockhoy, but lists one Willem Clasen, who had married Plockhoy's widow.(18) Plockhoy and his wife had one son living with the Clasen's, and the couple had two daughters of their own, the older of whom was married by 1673.(19) This suggests that Plockhoy must have died during or soon after the plundering of his settlement. His widow was also deceased by the time of the 1671 census, but an interesting conclusion drawn by genealogist Craig is that "the 'child" in Willem Clasen's household in May 1671 was the blind boy Cornelis Plockhoy, Clasen's step-son, who subsequently married a woman named Judith. In December, 1693, Cornelis and Judith deeded their Lewes lots to his cousin, Cornelis Wiltbanck, and moved to Germantown. So it was not the father, Pieter Cornelis Plockhoy, who turned up at Germantown in 1693, but his blind son, Cornelis Plockhoy, with his wife Judith.

The first person listed in the census was Cornelis Wiltbanck's father, Helmanus, his mother, their two sons, and one servant.(20) Helmanus was married to Janneken Cornelis, sister of Pieter Cornelis Plockhoy. In 1669 when more order was needed in the settlement, the colonial governor of New York appointed Helmanus Wiltbanck and Willem Clasen as sheriff ("chief justice") and commissary ("justice"), respectively.(21) Craig believes that when Plockhoy died (or was killed) "leadership of the settlement had passed to Plockhoy's brother-in-law Helmanus Wiltbanck."(22)

Another person listed in the census was Herman Cornelis, the younger brother of Pieter Cornelis Plockhoy.(23) Craig reports that Herman "had served at the Dutch fort at the Whorekil in 1660."(24) In a footnote, Craig remembers that "Plockhoy's proposal for his settlement, submitted in Amsterdam in 1662, showed a detailed knowledge of the Horekill obtained from an unidentified soldier returning from there,"(25) the implication being that Herman was that soldier-informant.

In a recent article in the Mennonite Historical Bulletin published by the Historical Committee of Mennonite Church USA (October 2002), Varden Leasa expresses doubt that these people were really Mennonites.(26) Otherwise, why would a veteran Dutch soldier have joined, notwithstanding the fact that he was Pieter Plockhoy's brother? Leasa's argument is tenuous as Plockhoy's second Dutch publication, Kort Verhael van Nieuw Nederlants… (Brief Account of New Netherlands…) reveals. Three of its articles of association clearly explain the kind of pacifist polity Plockhoy had in mind, and how Mennonite pacifists and armed guards could have co-existed in his settlement:

Article 40: It is further recommended that every colonist who feels personally free to do so provide himself with that which is necessary for his defense, at least with a firelock, pistol, and broad sword, powder and lead in proportion.

Article 41: The Mennonists and all those who could not conscientiously do so should in relation to this regulation and also in relation to guard and other military service [see Article 33] pay a certain tax if the community would desire or if a majority vote would so indicate.

Article 42: They will also be exempt from all voting on defense matters and fortification, and from orders from officers in this relation and concerning military service.(27)

In a self-governing "commonwealth" on the colonial American frontier, with threats of invasion by European raiders of English (1664) and Swedish (1673) nationality, not to mention the assumed threat of the native Americans, Plockhoy had implemented a two-kingdom ethic that subsequently characterized American Mennonitism for three centuries.

Most of the interest in Plockhoy's witness to the Christian world has centered on his communitarian vision. Socialist writers have acclaimed him as the father of the co-operative movement.(28) Several writers of American history have called him a pioneer of social and political democracy. Others have taken note of the fact that he was an early voice raised in America against slavery.(29) In the concluding paragraphs of this article, I would like to focus on his doctrine of the church in the context of his Mennonite roots in the Netherlands. First, readers might question why, if the remnant of Plockhoy's Delaware settlement were really Mennonists, they did not establish a Mennonite congregation in the hamlet of Lewes. Their Dutch Mennonite identity was likely not less denominational than it was at Germantown, and Plockhoy's Collegiant orientation would likely have minimized that identity for his own group.

Plockhoy grew up in the Mennonite church at Zierikzee, Zeeland. His pastor was Abraham Galenus, whose son, Galenus Abrahamsz de Haan became pastor of the large Mennonite Church in Amsterdam (1648-1706). Plockhoy and the young Galenus were friends and deeply influenced by the open-minded theology and ecumenical spirit of their pastor/father.

There was a deep division in the Mennonite churches of Holland between the Flemish and the Frisians, a division that was transported to West Prussia, Russia, and even America. It was caused by petty issues related to church polity and discipline. The Flemish generally were more severe in church discipline and the Frisians were more liberal theologically and more susceptible to acculturation and ecumenicity in their Dutch, Prussian, and Russian environments.

The Mennonite church of Zierikzee refused to take sides in these controversies and were banned as "stillstanders" by both the Flemish and the Frisians.(30) Pastor Galenus was wary of confessions of faith that divide members and warned against a literalist approach in biblical teaching. He believed that Christ alone is Lord, even of the Scriptures.

Plockhoy and the younger Galenus may have gone to Amsterdam together. Here while attending the Mennonite Church, they participated in discussion meetings of the so-called "Collegiants," an ecumenical association started in 1620 as a by-product of Calvinist-Arminian disputes over the issues of predestination and creedal authoritarianism.(31) When the more liberal Arminian ministers were excommunicated, a number of the Reformed churches whose ministers had been deposed continued to meet without a minister. They came together to pray and sing hymns, and to read and discuss the Scriptures on their own. For Scriptural interpretation they relied on the extemporaneous testimony of anyone who felt led by the Holy Spirit to speak for the enlightenment of the group. For this they found Scriptural authority in 1 Cor. 14:1, "Make love your aim and earnestly desire the spiritual gifts, especially that you may prophesy." They called their meetings "collegia" or "colleges." Although ministers often attended these meetings, the Collegiants were a lay, anti-clerical movement.

The Collegiant movement found a ready response in Mennonite communities in which the more open-minded members had become disenchanted by the rigid, dogmatic, legalistic, authoritarian structures in the more conservative Mennonite groups and especially by the doctrinal bickering between them. Mennonites were not only drawn to the colleges but gradually took over their leadership, which often met in the Mennonite meetinghouses. Thus in Amsterdam, the main leader of the college was Galenus Abrahams de Haan, who then became one of the main leaders of the entire Collegiant movement.

As already indicated, Plockhoy believed that state-churchism was Antichrist; and his English booklet, The Way to the Peace and Settlement of these Nations, proposed that collegia be established in every community as a viable alternative. He plead with Oliver Cromwell,

Suffer by no means (you having respect to the honour of Christ) that any Confession of Faith be set upon the throne as equal with the holy Scriptures, for Confessions are only to distinguish one sect from another. Assist not with the sword or money of the Commonwealth any sect or person in particular, that you may not hinder the truth (which hath been long kept under) from manifesting itself by its own power…; for magistrates (as magistrates) have no permission to favour any sect or person in particular. If any person will be a member of a particular congregation, he hath his liberty as well as others, and may honour the same with his presence, his tongue, his pen, and his own money, but not with the sword or money of the Commonwealth, for the magistrates, being chosen by the generality of the people, are to stand immovable in the Centre as moderators between all sects.… If the power to defend the good against the evil in all countries be ordained of God, Romans 13, then reason requires that all sorts of people of whatsoever nations, being in one country together, should be protected.…

The Lord Jesus hath taken captivity captive: that is, put those to shame those who held others captive… and gave gifts unto men that they should not be led astray again, viz., he gave as means to salvation Apostles, Prophets, Evangelists, Pastors and Teachers, whose doctrine alone… we should set on the Throne, that in all Christendom, being divided into divers sects (as formerly the Jews were) a general way of church meeting may be instituted for the hearing of God's word read unaltered and unsophisticated, leaving freedom for all to assert their own apprehensions and understandings upon the lessons of their Master Christ, without being tied to one another's opinions.…

We desire from the bottom of our hearts that all might be gathered together under that one name, and that your Highness… would institute as an eternal memorial and example to all… in every city or county throughout England, Scotland and Ireland, one general Christian assembling or meeting place, in such a form that all people may see one another round about by the help of seats, rising by steps, having before them convenient leaning-places to read and write upon, also one desk aloft on one side or end [from which] to hear the holy Scriptures read at a set time, giving freedom after the reading to all people to confer orderly together concerning the doctrine and instruction of their Lord and Master Christ.(32)

Out of this Collegiant method of dialogue, there emerged in the Mennonite Church of Holland and especially in the Lammist Church of Amsterdam a theology that was at once Christ-centered and open minded to congregational variance. Plockhoy's enduring witness to Christians in general and Mennonites in particular is clear: If they want to be peacemakers in a conflicted world, it is self-evident that they must overcome their chronic disunity in a more radical demonstration of love and ecumenicity.

Whether or not there was any continuing Mennonite witness among the surviving Plockhoy remnant at the Delaware is simply not known, but Plockhoy himself left us enough of an enduring legacy to continue the speculation, and indeed to give heed to his witness and learn from it. At the very least, it is a fascinating story.

1. Leland Harder, "Plockhoy and His Settlement at Zwaanendael, 1663," Mennonite Quarterly Review 23 (July 1949): 186-199; Irvin B. Horst, "Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy: An Apostle of the Collegiants," Mennonite Quarterly Review 23 (July 1949): 161-185.

2. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy from Zurik-Zee: The Study of a Dutch Reformer in Puritan England and Colonial America (Newton, KS: Board of Education and Publication, General Conference Mennonite Church, 1952), 62.

3. E. B. O'Callaghan, History of New Netherland, or New York under the Dutch, II (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1855), 318.

4. C. Henry Smith, The Mennonites of America (Goshen, IN: By the author, 1909), ch. 3.

5. Smith, 83.

6. Leland Harder, "Plockhoy and His Writings: The Study of a Social Reformer" (M. A. thesis, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Michigan State College, 1950).

7. Leland Harder, "Plockhoy and His Settlement at Zwaanendael, 1663," Delaware History 3 (March 1949): 138-154.

8. Leland Harder, "Plockhoy and His Settlement," MQR.

9. Horst, "Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy."

10. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy.

11. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy, 50-51.

12. O'Callaghan, 538.

13. Irve Tunick, "The Valley of the Swans" (radio script, May 27, 1952, program #746). Copy at Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, SA.II.315.

14. C. H. B. Turner, ed., Some Records of Sussex County, Delaware (Philadelphia: Allen, Lane & Scott, 1909).

15. Original Land Titles in Delaware Commonly Known as the Duke of York Records, 1646-1679 (Wilmington, DE: 1899).

16. Smith, 93.

17. Peter Stebbins Craig, 1671 Census of the Delaware (Philadelphia: Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, 1999), 73-82.

18. Craig, 76-77.

19. Craig, 77.

20. Craig, 75-76.

21. Craig, 74.

22. Craig, 75.

23. Craig, 80-81.

24. Craig, 80.

25. Craig, note 298.

26. Varden Leasa, "Setting the Record Straight on Pieter Plockhoy--Delaware's First Mennonite," Mennonite Historical Bulletin 63:4 (October 2002), 5.

27. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy, 194.

28. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy, pp. 74-75, especially John Downie, a member of the Cooperative Union Limited in Manchester, England and author of the pamphlet, Pieter Cornelius Plockboy [sic]: Pioneer of the First Cooperative Commonwealth, 1659: His Life and Work (Manchester: Cooperative Union Ltd., n. d.). Reprinted from the Cooperative Review. See also Jean Seguy, Utopie Coopérative et Œcuménisme: Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy van Zurik-Zee 1620-1700 (Paris: Èditions Mouton et École Pratique des Hautes Études, 1968).

29. Leland Harder, "Plockhoy and Slavery in America," Mennonite Life 7:4 (October 1952), 187-189.

30. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy, 11.

31. N. van der Zijpp, "Collegiants," Mennonite Encyclopedia I (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1955), 639-640.

32. Leland Harder and Marvin Harder, Plockhoy, 109ff.