J. F. Balzer, 1918

September 2004

vol. 59 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2004

vol. 59 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

Dan Tyson lives in Montezuma, New Mexico, on the campus of The United World College of the American West, an international boarding school from which he retired in 1998. He has been a pastor of Congregational churches and an admissions counselor at a number of colleges.

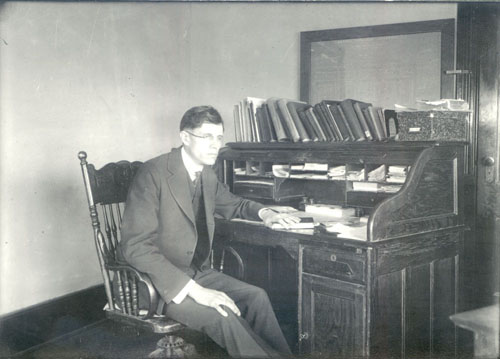

J. F. Balzer, 1918

Difficult questions loomed for the Bethel College (Kansas) community in October of 1916. What language policy should prevail as the college prepared youth from German-speaking families for futures in a society where English dominated? How should Bible knowledge be transmitted so that the biblical faith of our people remained relevant and our churches supplied with effective leaders? And for modern Anabaptists in America who had eschewed millennialism, how could Mennonites act in the world and on the world to convert it into a place where peace and justice prevailed? Would a vote for presidential candidates Woodrow Wilson or Charles Evans Hughes be the more righteous choice?

Jacob Frank Balzer, a promising young teacher of Bible and Greek appointed in 1913, had been made academic dean in 1914. He seemed an unlikely firebrand. In 1905 he had graduated from Bethel's two-year associate of arts program. At Bethel he met and became engaged to Alieda Van der Smissen, the daughter of a Mennonite pastor. They waited seven years to get married. Meanwhile Balzer finished undergraduate work at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, and went to the University of Chicago Divinity School for further Bible study. He earned his master's degree in June of 1913, after which he finally felt qualified to accept a teaching appointment at Bethel and the responsibilities of marriage. In 1914 President John W. Kliewer ordained him to the pastorate in the Bethel College Mennonite Church.

By the time he began teaching at Bethel, Balzer was a partisan of the progressive ideal of the "Social Gospel." Shailer Matthews, Dean of the University of Chicago Divinity School, was a leading proponent of the Social Gospel movement. Matthews became Balzer's mentor and lasting friend. Chicago was a laboratory for the development of social work and settlement houses. These were secular institutions that built community and promoted Christian democratic ideals of economic and social justice. During Balzer's years of study, the University of Chicago had the nation's preeminent sociology department. Professors Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, William Thomas, and Florian Znaniecki taught there.

Balzer's Chicago diary in the summer of 1912 records his enthusiastic participation in the founding convention of the Progressive Party which selected Teddy Roosevelt as its candidate. He was gleeful at the prospect that this entry would split the Republican vote and facilitate a win for Wilson. Balzer was strongly infected by Wilsonian idealism, the 14 Points and the slogans, "The War to End Wars" and 'The War to Make The World Safe for Democracy". This enthusiasm, departing from the pacifist tradition, undoubtedly was a factor counting against Balzer's continued tenure at Bethel in 1916. Balzer's interest in civic involvement was also reflected in his election to the office of "Constable of Newton Township" in the November 1916 election. He saved the certificate of that election in his files. Today it is in his papers at the Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel College. Could this have been an early sign of his restiveness with the Mennonite tradition of non-participation in government affairs?

Balzer was well aware that his Chicago Divinity School education would be a considered a liability among some conservative Mennonite believers. In the spring of 1913, when he was about to finish his program at Chicago, he described his wariness of "heresy hunters" in his diary as he contemplated a sermon he was to preach in the Berne, Indiana, Mennonite Church at the invitation of his prospective father-in-law, Carl H. A. van der Smissen. He knew that congregation had members who believed that Chicago was spawning heretics. They would be on the alert to spot the least hint of heresy in his sermon. He expressed great relief in his diary when the Berne folks found his sermon acceptably orthodox.

In October of 1916 Dean Balzer gave a chapel talk at Bethel College that ignited the so-called "Daniel Explosion"--a battle between liberal insurgents and conservative traditionalists. He suggested that the book of Daniel was likely written in the second century B.C.E. rather than during the exile of the fifth century B.C.E. The next day in chapel, Gustav Enss, a conservative colleague, directly challenged Balzer's position on scriptural interpretation, calling his ideas "dangerous and unacceptable". The issue was joined, and the insurgents lost. Over the next three years Bethel lost five young liberal faculty members, including Balzer.

In 1917 Balzer was granted a leave of absence from Bethel College to return to Chicago for further study in religion and sociology. Although the president of Bethel assured him that his faculty position would remain open upon his decision to return, it was clear to Balzer that the patrons and trustees who controlled Bethel did not really want to have a professor teaching there who had his kind of education. So he began to search for other venues. It was not easy and the choices he made out of necessity and conviction marginalized him further from the Mennonite center.

During the wartime period when he was "exiled" in Chicago, Balzer sought a nomination through the YMCA as a chaplain to young men from the historic peace churches who were in alternate service units such as the Army Medical Corps as non-combatants. He was given encouragement at the initial stages of application for this position. The approval for such an appointment had to be reviewed at the highest level of the War Department. It never came. He wrote in tones of rare bitterness in his diary that he believed he was rejected because of two questions he had not been given the opportunity to rebut. The first question was, "Could he, from his pacifist religious background, be trusted not to undermine the fighting morale of combat soldiers with whom he would inevitably have some contact?" and the second was, "Could he, a German-speaker from a German immigrant community, be trusted in the war theater to support the official anti-German line?"

Clearly it galled him to be confronted with the reality that he could be defined as something other than a loyal citizen of his country, on the basis of his religious and ethnic background.

After further graduate study in sociology at the University of Chicago, Balzer accepted a position on the Carleton College faculty teaching Greek and Bible. In 1922, he joined the First Congregational Church of Northfield, Minnesota. The Congregational Conference of Minnesota respected his Mennonite ordination. The polities of these denominations were similar. The constituencies of both denominations included considerable diversity on issues of biblical interpretation.

Balzer family ca. 1928: Margaret, Charlotte, Alieda, Wilma, Jacob.

American society changed rapidly after World War I. Automobiles, radio, advertising, movies, and the volatile stock market fostered unanticipated cultural responses. Institutions of higher education also changed. Declining offerings and enrollment in Carleton's religion department threatened Balzer's faculty position. He had hoped to transition into the sociology department for additional teaching responsibilities. But Carleton's management felt his academic credentials in sociology weren't strong enough to justify appointing him as department chair. So Balzer was released.

Jobless in the depth of the depression with a wife and three daughters to support, Balzer's prayers must have taken on added fervor. Carleton's president, respecting his winning personal qualities, told him he could remain in Carleton's employ if he combined fund-raising for the college along with some teaching. The prospect repulsed Balzer. He replied "I am a teacher! I am not a fund-raiser." The Great Depression shriveled the resources of many a private college and academic openings for teaching positions in Greek, Religion, and Bible were unavailable. Had he remained a Mennonite perhaps some teaching or preaching position would have been available for him. But he had crossed that bridge. What could he do?

In 1933, Balzer became one of the regional directors for the Minnesota office of the National Recovery Administration (NRA), an agency that was the center of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's first New Deal. This position gave Balzer a chance to use his talents in behalf of social justice in his country. This was his opportunity to prove how good an American he could be--an opportunity that had been denied in World War I when his application for a military chaplaincy had been turned down.

The task of the NRA was to foster voluntary regional economic cooperation to ameliorate the effect of two destructive trends set in motion by the Great Depression: price competition and labor competition. The NRA undertook the impossible task of radically and rapidly changing the mentality of American business culture at the community level. The method was to convince competing businesses to organize trade agreements that set mandatory affordable minimum prices for merchandise items high enough to sustain activity. Merchants who were party to these agreements were not free to lower prices in order to drive competitors out of business. Naturally, this restriction on business freedom was a tough sell, even though in theory it gave businesses protection from destructively aggressive price competition while still providing them with the incentive to compete for customers with service quality and efficiency.

In addition to this voluntary cooperation on price control was the requirement that employers increase wages. The rationale for this was that wage levels, if left to the unregulated labor market under conditions of extraordinarily high unemployment, would fall to levels that left the masses without sufficient means to consume enough goods to sustain the economy.

The NRA project was audacious. The fact that it did pass stands as a measure of the level of economic desperation that gripped the United States in 1933. The world's unregulated capitalistic economic system had faltered badly and a gathering international proletariat saw hope in the alternative command economy introduced by the communist Soviet regime after the Russian Revolution. Something radical, but non-communistic, had to be done in America and done quickly. The survival of democracy appeared to be at stake. Balzer, with personal family needs akin to the needs facing other unemployed men in 1933, saw an opportunity in this New Deal job. It is not difficult to understand why this prospect might interest him or why his experience as a teacher and preacher of the Christian social gospel had equipped him to inspire faith in this new democratic economic gospel.

The NRA project depended upon successfully fostering a very high - sacrificially high, in theological terms - level of community cooperation. America had been settled by colonies of families practicing high levels of mutual cooperation. But with success and security, Americans, relishing freedom, tended to focus more on taking care of themselves and their own, rather than acting out of a responsibility for the general welfare of society. Capitalism's competitiveness had become endemic and individual welfare took precedence over social solidarity.

In seeing the need to soften the harsh consequences of economic competition, the NRA was simply being radical in the sense of returning to an earlier mode of cooperation when economic activity was driven by social, rather than individual gain. For Christians there was the model of the first century church when small groups of Christians shared life's necessities while awaiting Christ's return. For Mennonite Christians there was the model of the early Anabaptist communities. These communities, under severe pressure from dominating antagonist regional governments, had to cooperate internally and externally in order to survive.

Mennonite communities historically represented their own kind of social cooperation. In 1941 Frank Balzer, Sr., Jacob Balzer's father, wrote an autobiographical essay at age 81. The elder Balzer wrote that when his East Prussian forebears moved to Gnadenfeld, Ukraine, from East Prussia in 1835 one of their first projects was to build a stout community granary. Thereafter each head of household donated a portion of the grain harvest to the colony's granary for storage in case of future community need. He wrote that the colony was blessed with a remarkable succession of favorable harvests. In 1877 when changes in the Russian policies governing the status of immigrants turned ominous, the common granary became the means of financing the colony's passage to America. Selling the wheat and rye from the community granary provided the necessary cash for 800 immigrants to move from Russia to America. The 1877 settlements in Mountain Lake, Minnesota, and in Harvey County, Kansas, were facilitated in part by this socialistic community compact. It must be noted, however, that capitalism was present in the part the railroads played in the move. Of course, the railroads were themselves beneficiaries of very generous land grants from the federal government. Obviously the way for railroads to cash in on this benefit was to encourage settlement and commerce in the territories their rail lines were laid out to serve. In fact someone has noted that 19th century Mennonite community governance was an ingenious blend of three diverse organizational modes: oligarchy, socialism, and capitalism. In America, of course, these modes had to be made to fit into a democratic society.

Balzer was also deeply influenced in his understanding of his responsibilities as a religious leader by the Old Testament prophetic tradition in which the human values of social and economic justice were primary. The goals of the New Deal resonated with Balzer's own Mennonite-honed interest in community values. His study with some of the founding lights of the new science of sociology inspired in him visions of how a democratic society could become better. The National Recovery Act offered Balzer the chance to apply sociological principals and test economic theory in real communities.

Frank Balzer, Sr's. 1941 essay reflected upon his life. He wrote of the early financial struggles as he started a business and a family in the new world after immigrating at age 18 from Russia to Minnesota. "The money situation [die Concurenz] in those years [1880 -1890] was very unfavorable, but I had good and honest friends; and what the currency situation threatened to destroy, the friendships helped to redeem.… But one thing I would like to mention here: Why does God wait? God can do very little for us, but He can do almost anything with us. So it meant, in this period, to grasp God's hand working with Him. The children all grew up. All received college education. Sickness--very expensive sickness came also. Demands came from churches, missions, Bethel College, Northern Bible Society, Bethel Hospital, and many others; but I could help with them all. I came gradually to the conviction that it all paid off to give God a chance to work with us. Will just mention that I maintained an Indian boy at $15 a year contribution. In Bethel College I have 9 votes; in the Bethel Hospital, 13 votes. I did not withdraw from the churches, but helped to the extent and manner in which I could." Frank Balzer, Sr. died in 1944.

Clearly Jacob Balzer, Frank's first born, had absorbed from his father the habit of serving God through service to community.

Balzer, in the archived documents, says little directly about his service in the NRA. He wrote many outline notes on light cardboard stock for the speeches he made to various business groups: trade and professional associations, Rotary Clubs, Chambers of Commerce, educators, and labor unions. The government argument was that consumption had to be stimulated. Jobless or under-employed people could not purchase what industry could and would produce if only a market existed. This argument had to be carefully articulated so as not to fan the passions of class division. Marxist theory loomed ominously in the minds of the under-class - as well as in the minds of the liberal intellectual elite--as a credible interpretation of capitalist failure. And the apparent success of Soviet economic practice made it absolutely critical that America recover her economic balance. "Pump-priming" was the economic metaphor that was particularly apt for Americans with rural backgrounds. It made sense that if enough "little" people were given a little more purchasing power they would collectively spend the country back into prosperity.

Balzer's daughter recalls that her father greatly enjoyed meeting so many interesting people on his NRA trips. But she also reported that he did not like his responsibility to "police" the agreements on prices and wages. NRA enforcement leverage for its policies depended upon what we would now rate as a pretty short and flimsy stick. The "carrot" given to cooperating businesses - those agreeing to minimize prices and raise wages to the trade standard - was a decal for the window. It was a blue eagle in defiant profile with spread wings boldly emblazoned with the N and the R and the A.

The "stick" of enforcement was to prohibit the display of that decal, if the business did not live up to the agreement. The effectiveness of this arrangement depended on widespread public awareness of and belief in the NRA's objectives. It was in essence a government sponsored boycott of businesses that persisted in remaining outside the agreed conditions of commerce. The NRA window decals served in the same way as a "union label" does to reassure the consumer that the product purchased not only satisfied a personal need, but also helped to improve the general lot of workers and, ultimately, the health of the economy.

The NRA lasted only two years. In 1935 the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. This judicial defeat prompted President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to try to "pack" the Supreme Court by adding liberal justices in order to protect other New Deal projects from intensely antagonistic detractors.

So Balzer was again out of a job. In late 1936 the combined opportunity as pastor of the First Congregational Church at Crete, Nebraska, and a position on the faculty of Doane College must have seemed providential. I met and came to know Jacob Balzer at the height of his dual pastor/teacher career in the summer of 1945. World War II had not yet ended. Having just graduated from Aurora (Nebraska) High School, I faced the prospect of being drafted into military service at my eighteenth birthday in September. I had begun college classes in June at Doane College in Crete, a small college town not unlike Newton, Kansas. Mill and grain elevators punctuated the prairie horizon. But the settlers in Saline County, Nebraska, were immigrants from Slovakia or Bohemia rather than German speakers from the Ukraine. At Doane in 1945, again as a college dean, Balzer's professional career once more faced challenges like those of the Daniel explosion at Bethel in 1916. Again, the context was a nation at war.

That fateful summer I was on my own away from home for the first time. Impelled by prudence more than conviction, I continued the habit of regular church attendance. Our family had always been Congregationalist. Jacob F. Balzer's dynamic preaching kept me bolt upright in the pew. His sermons had an intellectual rigor and a convincing clarity that was more intensely appealing than any preaching I had ever before heard. What was it that he had that other preachers in my limited experience didn't? I was curious. My classmates, also new to Doane, were equally curious. We never missed a sermon. We noticed that some of our favorite professors never missed a sermon either. Already we had observed that college "intellectuals" as a class were wary of "God-talk" as it was commonly practiced. How had Balzer undermined the confidence of this intellectual class in their skepticism? Or was he turning their natural tendency of skepticism toward their unbelief?

That summer I had to make a decision about the draft. When I appeared before the draft board of Saline County in Wilber, Nebraska, I registered as a "Conscientious Objector." Naturally, the board questioned my authenticity. In the conversation, I stated my intention possibly to study for the ministry. The board declined to register me as a "conscientious objector." The existence of that category acted as a thorn to the operation of a draft board because it denied that war is a legitimate national activity. Instead they gave me a "IV-D" classification for pre-theological students. Such a deferment could be rationalized more easily. After all, a nation so de-humanized as to go to war stands in need of all the future activists for peace that any of the Churches might train for leadership.

Did Balzer have anything to do with this decision? I honestly think not. I never discussed my decision with him. I was more influenced by a young roommate that summer from Indiana who came to Doane already aflame with a passion for conscientious objection, picked up from such pacifist firebrands as A. J. Muste and from such organizations as the Fellowship of Reconciliation. I read his literature, listened to his arguments, and felt the flush of excitement that, for the young, attaches to being a social rebel.

Self-absorbed as I was in my personal decisions about the draft, my educational and vocational choices in the summer of 1945, I was completely oblivious to the power struggle at Doane, being played out by those who really had the reins of institutional power: the trustees and those to whom they delegated the tasks of academic management: the President, Reverend G. Bryant Drake, and the dean, Reverend Jacob F. Balzer.

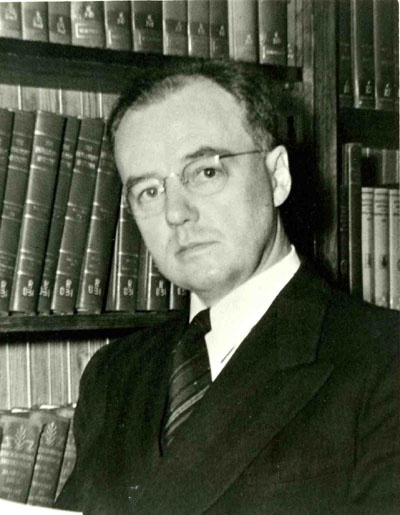

G. Bryant Drake. Credit: Dan Tyson.

Bryant Drake had been inaugurated President of Doane in 1942. Shepherding private colleges through the depths of the depression had been a fierce struggle. Middle-class families had turned to the alternative of lower cost public universities. The draft for military service eliminated most males of college-going age from the applicant pools. It took persons of vision to undertake the responsibilities to keep a college alive in those times.

Institutions tend to revert to their "base" in difficult times. Like many liberal arts colleges founded by denominations to educate their own future leadership, Doane had been founded originally by former New England Congregationalists who followed the frontier westward. Doane had loosened its ties to the denomination, as had many such colleges in the post World War I era. Yet the Congregational Board of Home Missions had begun to see the need to support the Congregational Colleges as part of the collective mission of the denomination. The Board of Trustees of Doane usually included ministers and influential affluent lay members of the most prominent Congregational churches in the region.

The selection of Bryant Drake as Doane's President in 1942 may have reflected the trustees' hope to revitalize a connection with the regional and national constituency of the Congregational Churches. Drake had started his ministry as minister to students of Iowa State University in Ames. During a 13-year long pastorate in Springfield, Missouri, he effectively served students attending the Congregational-related Drury College in that city. Doane's treasurer, Glenn Buck, who in the depressed thirties had traveled Nebraska gleaning students from families able to pay the meager tuition, understood the value of a denominational connection. He often summed up Doane's daunting student recruitment task by pointing out that every town in Nebraska had a Methodist Church whose member families were expected to send their children to Nebraska Wesleyan College. There was not a Congregational Church in every Nebraska town.

Hugh Butler. Credit: Dan Tyson.

Doane's most experienced trustee was Hugh Butler, a graduate of the Doane Class of 1900. He was my great uncle. Butler had joined the Board in 1914 and served continuously until his death in 1954. He had ties to the Crete community beyond those of Doane College. After working as a surveyor and a construction engineer for the Burlington & Quincy Railway, he had returned to Crete as an employee of the Crete Mills. Milling was in his blood, so to speak, as his father, an early settler in Furnace County, had been a miller in the water-powered days of the Cambridge Milling Company on the banks of the Medicine Creek in Cambridge, Nebraska. In the classical Horatio Alger hero style, Butler married the boss's daughter, Faye Johnson, and rapidly rose in his father-in-law's company as a manager of one of his several mills. Perceiving where the real money was in this branch of the food industry, Butler moved to Omaha in a few years and went into business as a grain dealer.

Grateful for his own education at Doane, Hugh Butler contributed regularly to his alma mater. In 1914 he joined Doane's Board of Trustees. He also served on the Board of Education of the public schools in Omaha. He was an enthusiastic Rotarian in its early proliferation of the business-service ethic and the establishment of clubs around the world. In the thirties, he was elected Rotary International's President. Nor did he neglect to become active in the political party whose platform stances conformed most closely to his own. In 1936 he became a Republican National Committeeman from Nebraska and in 1940 was elected to the U.S. Senate. He was re-elected in 1946 and in 1952 and served until his death two years later.

The Doane in 1942 to which new president, G. Bryant Drake, came was, like many denominational liberal arts colleges, under siege in the competition for funding and for student enrollment. Butler, now chairman of the Board, had used his new status in Washington as U.S. Senator to procure a contract with the Defense Department for Doane to train officer candidates for the U.S. Navy under the V-12 program. The terms of this contract specified that Doane provide a year of college level instruction to young men who qualified in mathematics, physics, navigation, English, and physical education. The latter qualification required Doane to build a swimming pool addition to the gymnasium. But the yearly cohort of new cadets assured Doane of having a reasonable gender balance in its total civilian plus naval student population during times when males of student age were already engaged in training for or fighting the war.

The contract also gave Doane the resources to employ the necessary faculty to provide instruction. One of Drake's early decisions was to appoint Jacob Balzer as Acting Dean.

Balzer's previous experience in college administration at Bethel, and his experience on the faculty at Carleton, gave him impressive credentials. Carleton was the most prestigious Congregational-related college in the country. By this time Balzer was well acquainted with his pastoral colleagues in the Congregational churches of the Nebraska Congregational Conference. He would be a useful agent to facilitate Doane's liaison with this important constituency. Neither Drake nor Balzer had earned doctorates, hence Balzer's appointment as Acting Dean. But they realized that in hiring additional faculty Doane must select teachers of proven ability in order to make more lasting the temporary boost given to the college by the war-time V-12 Program.

President Drake found in Balzer not only an experienced academic administrator, but a thoughtful intellectual with an established positive relationship with the local community and with members of the inherited faculty. This was more than just an affinity of their common ministerial vocations. They found they had similar hopes for a truly liberal arts curriculum, taught with verve and imagination - a curriculum that liberated students from the grip of provincialism and dogmatism be it theological, political, or social.

Perhaps they began to succeed too well. Doane did employ a new faculty contingent including some very experienced creative professors. Balzer was delighted. In fact he planned an innovative course as a part of the core curriculum in the social sciences called "Creative Biographies" which was taught by an artist, a historian, a psychologist, an economist working as a team.

But this sudden surge of "alien" synergy troubled some of the local Doane constituency. Perhaps they feared that this push toward higher academic standards and for national prestige would marginalize their influence. Some of the new faculty were, in fact, not only refugees from European fascism, but had previously angered conservative administrations in the first U.S. colleges to which they had fled. At least three of them were veterans of a "red" scare at Olivet College in Michigan in 1942. In the thirties mindset, one had to be very cautiously anti-fascist or be taken as a communist. One of the new professors, a European artist, persisted in wearing a beret, a clear signal of non-conformity. Another one of the new and young professors fell in love with a student. She transferred from Doane to graduate from another college but then came back to be his wife. And there were many rumors about radical ideas presented in classes. Antagonists saw these events as evidence of communist-like behavior. Just out of curiosity I chose, myself, to read Das Kapital and write a paper on Marx in an economics class in 1946.

Gossip and rumors spread. Senator Butler, chairman of the Board, felt obliged to do something. Though in the Washington of his day there was no beltway, the Washington mentality, struggling with war-worries and ideological threats, then as now found it difficult to preserve a balanced perspective. Senator Butler had come to Washington at a bad time. His country had been attacked at Pearl Harbor and was in a state of total war. His party had been in the minority since 1933 and seemed destined to remain in that position for some time to come.

In addition to these besetting difficulties, Butler had to deal with personal tragedies and limitations. His only son died at age twelve. Following his election in November of 1940 and before he took office, the car Butler was driving skidded on the ice in bad weather and his wife, Fay, was fatally injured. So it was a troubled, lonely man who took office. One of his recent Nebraska predecessors in that office was Senator George Norris of McCook, an Independent, who had developed a national reputation for his probity and style. It was an image that Hugh Butler was ill equipped to emulate.

Butler was accustomed to executing his decisions promptly in business. Political accomplishment was more elusive. But if he couldn't straighten out the mess in Washington as a new boy on the block, there was still his responsibility as chairman of the Board of Trustees at Doane College where he was unquestionably the senior player. Some of his close friends and local college trustees informed him that there were "communists or communist sympathizers on the faculty" and appealed for him to intervene. In Butler's mind, Dean Balzer was supporting a coterie of liberal faculty in the social sciences and humanities who seemed so far left as to be dangerous. Three of them had come to Doane from Olivet College which had undergone a purge of its so-called "red" faction a few years before. Balzer was vulnerable because he lacked a doctorate and was serving in a temporary capacity as acting Dean.

Drake, as Butler's appointee, supported Balzer, but could hardly thwart Butler's insistence upon replacing Balzer as Acting Dean and firing four of the recently employed liberal faculty coterie who, according to reports from Butler's local informants, seemed to be wresting Doane away from her provincial roots. Drake did prevail upon the Board to rescind those firings, but the damage was done. Three of the four found other positions and resigned their positions. The fourth vowed to keep a low profile, mind his steps, and stay on until he could make a graceful and voluntary move. He left in 1947. In 1945 Butler hired a new dean, Dr. Kenneth Brown, to replace Balzer. Brown had the correct credentials and a willingness to do Butler's bidding in the conduct of his deanship at Doane.

On April 1,1947, President Bryant Drake wrote a long memorandum to the Board of Trustees. He described in detail the problems Drake had experienced with the Board in his attempts to lead the college. On page six of this memorandum Drake wrote in defense of Balzer:

There is definite criticism of the pastor of the First Congregational Church, who was forbidden by vote of the Board to teach the fall semester, 1945 and until the Dean [Brown] not the president, should invite him to return to the faculty. The Dean, without any pressure from the president, invited him to teach double his ordinary number of hours (6 instead of 3) the second semester of the 1945-46 academic year, and this year prevailed on him to teach seven hours. Incidentally, the minister of the First Congregational Church has had more graduate work than any other member of our staff, and in the opinion of many serious students is about tops as a teacher. The power to employ him has been taken out of my hands by vote of the Board, but I rejoice that he is again on our staff, for in my opinion he strengthens our faculty, for he is a man of great intellectual vigor and true scholarship. This year he teaches a course in sociology, which is one of the most popular courses on the campus, and beginning Greek, which could not have been offered if he had not been available.

President Drake realized the hopelessness of his position and in 1947 moved on to become Secretary of Higher Education of the Board of Home Missions of the Congregational Churches. Dean Brown apparently determined for himself that criticisms leveled at Balzer were without foundation and continued his employment. But quite naturally, Balzer was dispirited by the direction the college had taken. One of his former students who had gone on to do graduate work in history upon returning to Crete for a visit with Balzer several years later recalled an uncharacteristically bitter comment Balzer made about Doane. In a private conversation he called Doane "the new Jr. College of Saline County."

In his public functions as a professor of sociology and as the pastor of the Crete Congregational Church, Balzer continued to inspire his students in class and his parishioners in church. In those respective pulpits he felt the freedom to speak the truth, and encourage others to seek the truth constrained only by conscience and scripture.

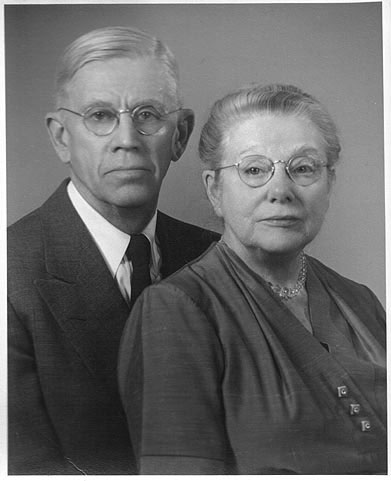

J. F. and Alieda Balzer, 1950s. Credit: Dan Tyson.

Balzer's life quest for a credible faith as a Protestant Christian should not strike us as extraordinary. It is rather the logical continuation into the 20th century of that quest for unmediated truth in the divine-human relationship that Martin Luther inspired in the sixteenth century. Anabaptists, particularly, have in subsequent generations produced leaders to meet the challenges. Balzer was another one of many contemporaries who stepped up to the contemporary challenges of the Christian mission.

The Lutheran slogan, "the priesthood of all believers," directly placed responsibility on each person of faith to develop a personal relationship to God for herself or himself - the scriptures being the guide. With the old hierarchical order of the Church of Rome in disrepute, the feudal order cracked, peasants revolted, and depending upon regional conditions and reform leadership, various modes of church discipline and order emerged.

The Anabaptists were the most radical in their insistence that their adherents make an informed commitment of faith confirmed with a baptism upon attaining the age of reason. The Anabaptists also affirmed the authority of the Bible in providing the substance of faith, and a church polity grounded in each local congregation of Christians. The leadership for Anabaptist churches emerged from the local membership rather than being sent down from a hierarchical superstructure.

The personalizing of faith and the apotheosizing of the local congregation placed new and strenuous demands upon individual believers. No longer could faith be taken for granted, carelessly accepted, or assumed as just part of the natural social order.

It must be conspicuously lived. Consensus required reasoned discussions about differences in scriptural interpretations.

The Bible, the Word which contained the authority for this new order, suddenly took on an enormously important role for Protestants. If the "priesthood of all believers" had any reality, each Christian had to know how to read. The availability of Bibles in the vernacular was a necessity. The development of printing was a concomitant of the Reformation. Popular education was born out of the Reformation. And so were the seeds of modern democracy sown.

Through persons blessed with uncommon gifts of intellect and spirit such as Balzer possessed, new light breaks into old communities of faith. "Daniel Explosions" and "Red Scares" are the concomitants of Protestant faith. We ought to worry more about their absence than their occurrences if we hope that our ancient faith can remain relevant to life as we now live it.

Mary Anne Pryor, Jacob Balzer's niece, captured the essence of her uncle in a poem written in 1970.

NO METAPHYSICS (1)

"No metaphysics is a metaphysics,"

repeated my uncle

loping from corner to corner

recounting the coup de grace of a bull session

some thirty years before. Sociologist, preacher,

professor, handyman, in the Great Depression

traveled for the NRA--strictly illegal,

as he loved to mention--at the age of seventy

gave up trimming trees

(under protest)

reveled in puns,

puzzles, and gadgets; built a rocking horse,

a reclining chair, and a miniature podium

with a live box elder bug juggling a cork-

perpetual motion.

His sermons exhilarating the college crowd,

the townsfolk taking the words on faith, he neighbored

the farmers, big-brothered juvenile delinquents,

encouraged the arts: graphic, harmonic, and thespian:

cherished his women,

followed his own genius,

and fathered three daughters, absolute individuals.

Fighting a life-long guerrilla action

against the logical positivists

of the U of Chicago,

a master teacher,

keeping in touch with his students

(till, as grizzled as he, they envied his vigor)

adopting all manner of persons,

when he laughed sitting down

his long legs bounced off the floor.

Pouncing on trends,

astride all changes,

perpetual motion,

his marginal notes

reaching from here to Arcturus,

historian to the last,

he deciphered from German script

the ledger

of his grandpa, the flour miller:

Groswiede, Berjansk, Minnesota.

From his Mennonite town.

one of the first two boys

To go away . . . to high school . . .

for graduation

the train, Mountain Lake to Saint James,

churning with tubs of peonies . . .

the day he died

three months from eighty-six

a nearly total eclipse of the sun,

precautionary

in view of the vast energy

unleashed on the universe.

1. ©Mary Anne Pryor, Moorhead, MN 1970. Reproduced with permission of the author.