Lawrence Hart at the Washita battle site, Oklahoma, Jan. 2000

September 2004

vol. 59 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2004

vol. 59 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

Raylene Hinz-Penner, former faculty member at Bethel College, is currently teaching in the English Department at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas.

In the fall of 2002 I made my first trip to Clinton, Oklahoma to interview Cheyenne Peace Chief and Mennonite minister Lawrence Hart. I see now that I had been working my way that direction for five years as I asked around, trying to find out who was writing his story. I didn't feel that it was mine to tell, nor did I necessarily choose to do it. A literature teacher and poet, I had assumed a Native American/historian/Mennonite theologian should be the one to write this story. I wanted to read it! Who should write it? Finally, I called Chief Hart and asked him if I could come to Oklahoma with a couple of questions. Lawrence didn't really know me, and I didn't really know him except for his public persona. My people, some of whom Lawrence knows, all come from Oklahoma, and I am a Mennonite, a fellow alum of Bethel College. That's all I had to recommend me when I asked if he'd give me some time. I haven't finished the story yet, but I can share my own experience. I wanted to know how Lawrence worked his way through his Cheyenne and Mennonite roots. I was powerfully drawn to his reconciliation and repatriation work, his restoration and preservation of Cheyenne culture, and I wanted to know how he wove his influences into a life. Tracing his journey includes the history of the white settlement of the Plains, the story of the Cheyenne tribe, the history of Mennonite missions in Oklahoma–in addition to the powerful details of Lawrence's personal life. What I do know at this point is that for me as a writer, the process of interviewing/ listening/ interpreting/reading/bringing to Chief Lawrence Hart's story has been powerful. Writing a life is sacred work. The very experience of talking with Lawrence and trailing him these past two years has been so far a sacred adventure for me.

Lawrence Hart at the Washita battle site, Oklahoma, Jan. 2000

Lawrence doesn't give me many details when we talk, which gave me great pause in our earliest conversations. I have come to see Lawrence as choosing not to try to educate me, but rather to allow me to educate myself. Initially, I feared that Lawrence had forgotten all the juicy details that would make his story a great read; indeed, some–he has. But mostly, he has not. The barebones review is simply his way of being, how he does history. Initially, because all my experiences with Lawrence had been listening to his public presentations, I saw him as a speaker, a preacher, an educator, a preserver of stories and history, a man of words for every occasion. He can be that man, and surely, he is always prepared to speak. When asked in advance, he carefully plans articulate public presentations, choosing (this is his gift!) the right words for the audience.

Left to right: Connie Hart, Betty (Bartel) Hart, Lawrence Hart, Nathan Hart. 1966.

When Lawrence and I are talking alone about his own past, however, he speaks slowly, after long pause. He is thoughtful, reticent, and I, as interviewer feel as if I am trying to follow his mind tunnel back like a flashlight in a long dark passage. Then he lightly touches down on a place, an event. He explains little. I soon came to experience this tactic, not as actual reticence on his part or lack of knowledge about the past, but rather as an unwillingness to coerce my viewpoint. He allows for my interpretation of events. It feels as if he is actually eager to see what I do with what I learn. There is usually more excitement in his eyes when I come back to him thrilled with what I have discovered, taking one of his leads, than there was in his initial suggestion. And for me, returning to a brief reference in a conversation unfolds a new world. I realize as I look back that Lawrence refuses to emphasize for me; he refuses to place priority. He respects the fact that his life's story is my interest, and he allows me to pull out the threads as I am able. This is a great gift.

Pastors and wives of Canton, Clinton, Hammon, and Seiling, Oklahoma, Indian churches at monthly meeting in 1966 in Hammon, Oklahoma. Left to right: Lawrence Hart, Betty (Bartel) Hart, Mary (Giesbrecht) Bartel, Norman Bartel, Lyman W. Sprunger, Adeline (Ensz) Sprunger, Anna Ruth (Baerg) Koehn, Clifford E. Koehn.

Also, I realize more and more that "the devil is in the details." Lawrence and I are not always interested in the same details! What details anyone cares about are personal, cultural, remembered through a private sieve. Sometimes he doesn't remember details I want him to remember for me, but of course, they are my details, my interests, my deductions about what is important in life. It is then that I realize again that this is my journey with Lawrence as my subject, my interpretation of his life, and he is generously sitting still for me to paint his likeness as I see it, not necessarily as he sees himself.

Like other great chiefs, Lawrence speaks in parables. He doesn't tell me what to think or show me how to see. He points. He rarely expresses strong attitudes. He simply recalls; he muses. People, places, events, stories (often in bare bones form) come to mind almost as if he had forgotten them until this moment when a certain question forces a recall. I like to think that this is sometimes true, that the very fact of my questioning unearths artifacts in his mind that he had nearly forgotten.

Left to right: Willis Busenitz and Lawrence Hart. At a gathering for Oklahoma Indian churches at Camp Mennoscah, Murdock Kansas, June 1965.

Sometimes I don't pick up on an event or a reference for its significance for weeks or months after we've spoken. I follow my own interests, explore what it is I want to learn in what I hear from him, digging after this or that tidbit which I find interesting. Months later I come back and find the kernel of what may be significant. Then, through cross references, the kernel may grow in importance. For example, Lawrence never tells me to go read something! Sometimes I wish he would. This process of conversing with Lawrence is also teaching me something about time. More and more I see the importance of taking time, waiting to see. The writing process becomes an exchange unveiling both our personalities. I am pushy and aggressive and impatient. I recognize these attributes in how I operate, even how I write. My tone has a breathlessness–even my punctuation. Words spill out and tumble all over each other if I allow them to, and my prose (before revision) is heavy with dashes which link unconnected ideas.

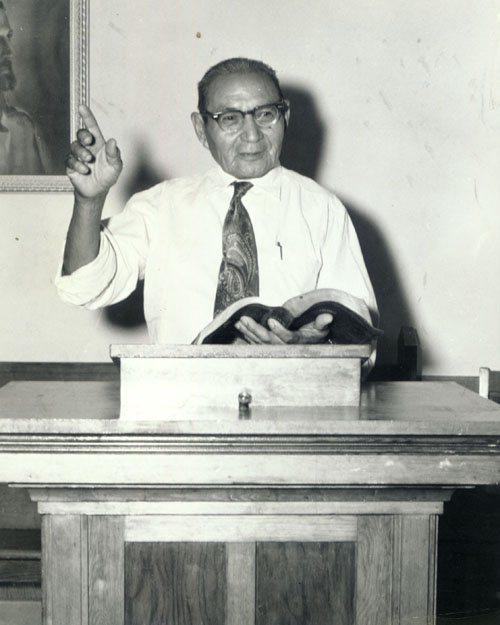

Homer Hart, Lawrence's father, 1965.

I have sat alongside Lawrence now for stretches of silence. I used to be self-conscious with even a short silence, worrying about what he was thinking, wondering if I should be asking something, fearing that I might be missing some chance in my eagerness to "pick his brain." More recently, it feels good to wait; I have developed some patience about outcomes, about "getting something" from him to write down. I have come to believe that the waiting is key to what I will write. I feel a constant need to rewrite. I go back now to what I wrote eighteen months ago and I want to write it differently. If I allowed myself to do that, I would never finish. I'd be in a constant state of rewriting because my thinking is constantly shifting; the entire picture is altered with every new discovery. I feel a sense of urgency, however, to share this story, and I press on. What I see now is Lawrence's way of being in this world. Lawrence is comfortable with who he is today, his personal amalgam of faith and learning. He understands that we each must do this, weaving the ethnic, cultural, historical, racial, gender threads in the way that we must. He will patiently wait to see what it is I will find.

Here's an example. I don't remember Lawrence ever making reference to what is commonly deemed "peyote religion." He spoke from the very first interview of the powerful influence of his grandfather, his grandfather's strong part in Native American Religion in Oklahoma in the 1930s when Lawrence was a child, but I had to read to find out that his grandfather was, indeed, a major figure in that movement, regionally, for decades, with powerful contributions to the rituals of the movement which last to this day. Here's how it came to me in an interview with Lawrence. As a kind of afterthought, he chuckled to remember the time he got on a plane to sit alongside a woman reviewing a book about Native American Religion. He struck up a conversation with her. She showed him the book. He concocted a test on the spot. "If the author of that book has done his homework," Lawrence told the reviewer, "that book should have my grandfather's name in it." Maybe that was the time he also told me that his grandfather had at some point changed his name. The "how" and the "why" of that name change intrigues Lawrence; he is always looking to make more inclusive his ancestry. It seems to me that he worries about who has been lost.

Jenny (Howling Water) Hart, Lawrence's mother, 1958 at Grand Canyon.

When I finally ordered my own copy of Omer C. Stewart's Peyote Religion: A History, I had already made the trip which retraced Lawrence's journeys with his grandfather to the Four Corners area, to the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation at Towaoc, Colorado where John Peak Heart (as he is listed in Stewart's index of personal names) established a relationship with his friend Walter Lopez, and where they together practiced the peyote religion throughout that region. These journeys with his grandfather, when he was very young, before his parents took him home from his grandparents' house to begin attending school, were profoundly influential for Lawrence. He spoke with pride during the first interview of the fact that his background includes this strain of Native American Religion for which his grandfather was a missionary. Even though Lawrence was a child traveling with his grandfather to play with the children of his grandfather's friends in Towaoc while his grandfather traveled the area teaching the rituals of the Native American Religion, these first six years set Lawrence's destiny.

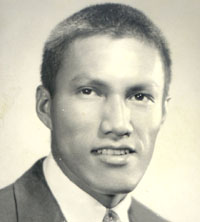

Lawrence Hart as a Bethel College student in 1953.

Stewart says that Southern Cheyenne Peace Chief John Peak Heart came to Towaoc every summer as a missionary to the Ute (traditional enemies of the Cheyenne) beginning about 1916 or 1917, (1) about the same time that Lawrence's father, Homer Hart, who had been baptized by the Methodists while he was away at boarding school, was received into the Hammon Indian Mennonite Church. John Peak Heart was one of the first Oklahoma missionaries to the Ute. He usually stayed with Walter Lopez, described as "a Towaoc shaman and sheepman," (2) but he conducted religious meetings on several reservations there.

Oklahoma was the cradle of peyotism, according to Stewart, a religion which sprung out of the reservation model set up by the U.S. government in Oklahoma. Stewart believes that the Cheyenne would have known about the peyote experience from their earlier years of raiding into Texas and Mexico. But bringing together these various tribes into the educational system put together for the tribes in Oklahoma (this is, of course, where the Mennonites enter the story), made the tribal leaders eager to band together for the practice of old rituals, for tribal power, and certainly, for tribal vision.

Homer Hart, 1935

Stewart believes that the Indian boarding schools where members of various tribes were brought together, taught English, taught basic Christian principles, taught the ways of white culture, formed the breeding ground for the peyote religion, an indigenous response to Christianity which wed Christian beliefs with Native practices. The list of Carlisle graduates who became peyotists, says Stewart, is well over a hundred. (3)

Corn Stalk and John Peak Heart. Photographed by Rev. Arthur Friesen. (credit: Lawrence Hart)

John Peak Heart was born in 1872, four years after the Battle on the Washita which would result in the Cheyenne being placed on the reservation. A student at Carlisle, he was a candidate for interest in the peyote religion. Stewart believes that the percentage of peyotists on any reservation at any time was likely only 35 to 50 percent. (4) Those who especially took to it were "young, newly educated Indians who found in it a form of Indian Christianity and often became its leaders. It was a ceremony they felt comfortable with, in which they could celebrate the Christian ideas they had recently learned at school in a setting that was familiar and indigenous." (5) Such a one must have been John Peak Heart. Add to that the fact that when Lieutenant Pratt had rounded up the rebel Indians on the Plains, after the Adobe Walls attack in Texas, for a three-year imprisonment at Fort Marion in Florida, where they learned English and Christian religious instruction, and many went on to study at Carlisle–the Cheyenne comprised the largest percentage of those taken, nearly half. Four young Cheyenne warriors, Co-hoe, Howling Wolf, Roman Nose, and Little Chief became prominent peyotists upon their return to Oklahoma. Those older Cheyenne would have been an influence on John Peak Heart.

Oklahoma mission "native helpers" ca. 1930? Left to right: Willie Meeks, Robert Hamilton, Albert Hamilton, Homer Hart, Kias, Harvey White Shield.

I once asked Lawrence why his grandfather quit going to Towaoc; he shrugged. "Perhaps he just got too old." He had certainly done a life's work. Stewart reports that John Peak Heart took his Half Moon ritual (known for its strictness, the John Peak Heart Way) to the Ute before 1918 and continued until 1952, when he would have been seventy years old, visiting Towaoc every summer. (6) His ritual instruction was also learned by Navajo leaders of Shiprock, who came to Oklahoma to study with him.

Left to right: Homer Hart, Jacob B. Ediger, Kias Short Nose, Agatha (Regier) Ediger, Guy Heap-of-Birds. Clinton, Oklahoma, ca. 1935?

In her book about her Mennonite missionary father, Rev. Henry J. Kliewer, who worked with the Red Moon mission at Hammon, Ruth Linscheid makes reference to the fact that Lawrence's father, Homer Hart, became, at a very early age, an important lay minister with the Mennonite mission. Of special interest to her is the story of Homer's younger sister Lucy, dying of tuberculosis at age seventeen. She says, "Little could be done to help her physically for her parents were strong believers in peyote." (7) (163). As Linscheid tells the story, there was a showdown in the Hart home between the medicine man and her missionary father over Lucy's illness. Apparently, the Mennonite missionary won and Lucy was baptized three days before her death. Later the same year, Homer's mother was baptized. Church records show that Chief John P. Hart too would be baptized some twenty-three years later in 1941. Around the time of Lucy's death Chief John P. Hart had begun his missionary work with the Ute practicing his indigenous Christian rituals. He would continue that work for nearly a dozen years beyond his baptism. He died in 1958, approximately six years after his last visit to Colorado.

Lawrence speaks with pride of his grandfather's mission work with the Utes as significant peace chief work. He thrills over the fact that his grandfather's 35-year mission was to the Utes, the traditional enemies of the Cheyenne. When I prepared to retrace Lawrence's journey with his grandfather to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Headquarters at Towaoc, Lawrence instructed us to stop at Two Buttes in southeast Colorado at an unmarked sacred site for the Cheyenne. There, as Lawrence's grandfather relayed to him, Cheyenne warriors resisted an attack by enemy Ute warriors; the Cheyenne warriors were able to save themselves, remaining atop the Buttes, holding their enemies at bay until they gave up and left. Lawrence's grandfather stopped at the Two Buttes with him to pray en route to Towaoc to minister to the Utes. Lawrence has stopped to pray there with his son, Nathan; he hopes that Nathan will take his son Micah to pray there also.

Jacob B. Ediger, ca. 1915

After reading Stewart's account of the work of John Peak Heart, I began to see the event of Lawrence's parents coming to take him home from his grandfather's house (across the yard) with all its ceremony in approximately 1939 in a new light. No doubt his parents did want to see to it that Lawrence would start first grade at the local Quartermaster School; they wanted to emphasize education. But one has only to read the missionary writings in The Cheyenne and Arapaho Messenger during those same years to recognize why Homer and Jennie Hart, Lawrence's parents, might have needed to bring Lawrence home.

Lawrence's father, Homer, was a highly valued Native Helper for the Mennonite missionary, Rev. J. B. Ediger, during this period at the Hammon Church. While Homer and Jennie Hart lived on the same farm place with his parents John P. Hart and Corn Stalk, longtime midwife for the Red Moon clan of the Cheyenne tribe, Lawrence's parents would have had to consider the Mennonite missionaries' disapproval of the Native American Religion. Rev. Ediger railed against the Native practices while he repeatedly praised the work of the Harts, on their farm and in the church. The Harts were the model Cheyenne family who complied and put up the mailbox so that they could receive the Messenger. The Harts were active in the local farming organizations, winning prizes for their produce. Jennie Hart organized canning sessions in her home, putting away food for the winter as the missionaries were constantly begging them to do. For having the best garden in the district, the Harts won the prize of a pig. The Harts shared their produce, especially with the missionaries. Beyond that, Homer and Jennie Hart were tireless church workers, Homer Hart often conducting services, attending training seminars, performing funerals, and translating for the missionaries. Lawrence's mother, Jennie Hart, taught Sunday School, decorated the church at Christmas, organized the children's Christmas program. They and their children were always mentioned for their memorization of the Christmas story, their sending in answers to the missionaries' Bible quiz questions. They were clearly the backbone of the Hammon church.

Red Moon mission station, Hammon, Oklahoma, ca. 1900?

Meanwhile, in patronizing tones, Rev. Ediger chastised those who didn't stay home and mind the farm, those who practiced Native ways, sometimes in language that hardly hides his cynicism. Announcing by name the death of "one of our older Indians . . . after a long illness," he notes: "That his eyesight failed years ago while he went about 'blowing' on people, giving them what he called the holy spirit did not help his grouchy temper. We often have been sorry for his wife and hope she will soon be at her place again in our Sunday services" (June 1933). One can only imagine what Rev. Ediger said to his assistant, Native Helper Homer Hart, about his father's practice of the peyote religion. Surely, Homer and Jennie Hart must have felt compelled to transfer their son Lawrence from his grandparents' home to their own Mennonite home.

Lawrence would follow his parents' teachings. He would go to a Mennonite college and seminary. He would become an important Mennonite minister and leader. But his grandparents' influence was indelible. He would be the Cheyenne Peace Chief his grandfather hand picked him to be. He was set on a course to shape a faith, theology, and way of life which would recognize the power of the Good News the missionaries brought without denying the pain the Cheyenne had suffered at the hands of the white invaders or discounting the importance of his role as leader of his people, responsible for helping them remember who they were. In the preface to his Social Science Seminar paper (a requirement for graduation at Bethel College), titled "Why the Doctrine of Non-Resistance Has Failed to Appeal to the Cheyenne Indian" a young Chief Hart poses a question to his people: "How soon shall we, if ever, reach the point of pacifism we once practiced long before the coming of the 'spiders'?" (8) His own life would be a steady and tireless journey toward that end.

1. Omer C. Stewart, Peyote Religion: A History (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 196.

2. Stewart, 196.

3. Stewart, 65.

4. Stewart, 97.

5. Stewart, 97.

6. Stewart, 294.

7. Ruth C. Linscheid, Red Moon (Newton, KS: Linscheid, 1973), 163.

8. Lawrence H. Hart, "Why the Doctrine of Non-Resistance Has Failed to Appeal to the Cheyenne Indian" (Social Science Seminar paper, Bethel College, 1961).