March 2004

vol. 59 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2004

vol. 59 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Professor of Music at Bethel College

Perhaps no more suitable beginning exists for an investigation of the piano works of Robert Schumann than this piece, Der Dichter spricht (The Poet Speaks), the thirteenth and last in the opus 15 set of Kinderszenen (Scenes of Childhood) composed in 1838. The piece not only represents the continual blending of literary and musical interests shown throughout Robert Schumann's life. One can also hear those enigmatic, original, and puzzling elements found particularly in the early works for piano. What did you think of the piece as you listened? Were you drawn into the music, or confused by it, or fascinated by its unusual character? If you were to select any one of those answers, you would certainly find company in Schumann's contemporaries.

The main focus of discussion will be with the piano works written in the decade between 1830 and 1840, with particular emphasis on the Davidsbündlertänze, composed in 1837. First, a few remarks about three aspects of Schumann's life. Though not a biography in the usual sense, these aspects highlight influences and events that simply cannot be ignored when looking at the composer's music.

Robert Schumann's lifelong interest and proven ability in the literary world of German Romanticism is easily traced to his familial influence. He spent his childhood in a cultured environment, and greatly admired his father, who established a very successful publishing business, specializing in both reference books of Saxony and in pocket editions of modern classics, many of which he translated.

Schumann showed early interest in both music and literature (and specifically poetry), and he was given piano lessons as a young child. He became passionate about the music of Franz Schubert and the writings of Jean Paul Richter. Yet when the time came to enroll at the University, it was his mother's wish (his father died suddenly when Robert was 16) that he study law. By all accounts, as a law student, Schumann was a prime candidate for the intervention of a modern-day college retention committee, and after one year each at the universities in Leipzig and Heidelberg, he informed his family that he wished to study music. Writing would not be abandoned, however, and was most in evidence during the ten-year period beginning in 1834 when he was involved with the music journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.

The long period of time dominated by a triangle of personalities began in the year 1830. Schumann returned to Leipzig in that year, hoping to pursue a career as both a pianist and composer, and became a pupil of Friedrich Wieck. Clara Wieck, the daughter, was already a seasoned performer, having given her first important public concert at age 9 at the Gewandhaus, the most prestigious concert venue in Leipzig. Friedrich was ambitious, difficult, driven, and obsessed with the training of Clara as a virtuoso pianist.

By the time of Clara's first extended tour in 1832, concluding with a long stay in Paris, there is clear evidence of a mutual attraction between Robert and Clara. Early in 1836, Wieck forbade any relationship to continue, formally beginning a process not ending until August of 1840, when at the end of a long lawsuit, the court granted the couple permission to marry.

Based on letters, diaries, and many contemporary sources, there is no question that the marriage of Robert and Clara was based on love, but the marriage was certainly not free of tension. Friedrich Wieck had in fact done what he set out to do: Clara was a virtuoso pianist. His bitter opposition to the marriage was certainly both personal and financial. Through Clara's triumphs on the stages of Europe he also gained a measure of fame, not to mention the large sums Clara was earning. At the height of her career at the time of her marriage, she was at 21 already a strong, determined woman. Robert's hope was more likely for a wife who would provide him with domestic peace - one whom he might persuade to forget the concert stage. Clara never did completely abandon her career, sometimes touring alone (leaving Robert lonely and depressed) or with him (often resenting the back seat he was forced to take).

During and after one of Clara's tours, this time in 1844 to Russia, Robert became both physically weak and severely depressed. Robert had already suffered a nervous breakdown in 1833, but this time the situation was far more serious, and Clara was forced to take over the care of the household, the children, and Robert. Drastic measures needed to be taken, but the family's move to Dresden proved rather unsuitable in the long term. Despite continuing illnesses and financial worries over the next ten years, Schumann managed to produce an amazing list of compositions, though not a list free of criticism.

Many authors have written about Schumann's final decline, suicide attempt, and institutionalization during his last two and a half years of life. No single diagnosis seems to fit all of the symptoms - severe depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, latent effects of syphilis? Should Schumann have remained at the asylum in Endenich, or was he well enough at one point to leave? Each new biography offers new insights, but questions will likely remain.

To begin a closer look at Schumann's early Romanticism, I would like to first examine the composer's role in the music journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. In the summer of 1833, a small group of writers and musicians began to envision a journal devoted primarily to new music, one more concerned with high artistic standards than the typical publications of the day. Eric Frederick Jensen describes the state of affairs as follows:

Nearly all of the leading music journals of the day were produced by music publishers. Works that they published were given priority and invariably received favorable reviews. The musical taste exhibited in the journals generally ranged from the innocuous to the deplorable. Vapid, salon music was assured of praise, there being a consistent market for it. The reviewers displayed a markedly conservative taste, and found little to recommend in the compositions of Chopin, Schumann, and others. (1)

From the beginning of the Neue Zeitschrift, Schumann was one of the central figures. The first issue appeared on April 3, 1834, and by the end of that year, following a series of problems with publishers and some of the original members of the group, Schumann was completely in charge.

Schumann was ideally suited for the task of running the journal. He was skilled as a writer, idealistic in his zeal to hold up only the highest of musical standards before his readers, and seemed to possess an uncanny sense of judgment about both new works and performers. Ronald Taylor, in his biography of Schumann, provides the amazing list of features mentioned in the editorial introduction to the first issue. Not only could one expect reviews of concerts and new music, but articles on all aspects of music, poems and other literary pieces, news from the musical centers of Europe, remarks from composers themselves about their works, and even the possibility of prizes for the best scores. (2)

During his ten years as editor of the Neue Zeitschrift, Schumann did appear to maintain these high standards, all the more surprising when one realizes that he began the job at the age of 24. He was especially known for promoting talented young composers, and two of his published pieces most frequently quoted because of the new composers they champion, are the first and the last. The first actually appeared in 1831in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung and gave a review of Chopin's op. 2 Variations. The late one, written in 1853, hails the appearance of the new composer Johannes Brahms. Obviously, Schumann did not err in his predictions of fame for these two composers! The journal was not reticent, on the other hand, to publish harshly critical reviews. Here are Schumann's words in an 1841 review of Alexander Dreyschock's Grosse Phantasie, op. 12, as quoted by Jensen:

This is the first substantial work by the young hero of the piano whom the papers speak so much of. Unfortunately, we are obliged to confess that it has been a long time since we have encountered a work so insipid. What poverty of imagination and melody, what expenditure in attempting to impose lack of talent upon us, what affectation over hackneyed platitudes! Did the young virtuoso have no friend near to tell him the truth, no one who, overlooking his facility at the keyboard, could draw his attention to the barren emptiness of the music? . . . This might be expressed more mildly; but impotence steps forth so pretentiously, it is impossible to stand by quietly. (3)

Schumann's work and influence with the journal would be perhaps interesting enough by itself. The addition of the Davidsbund makes everything - his writing and his music of this period - fascinating. Davidsbund - the League of David, and hence the connection to the title of my paper - very likely had some origin in the circle of musician and writer friends of Schumann who gathered regularly in coffeehouses and homes to discuss the state of music and the arts in general in Germany. The League of the Neue Zeitung, however, existed only in Schumann's mind. The purpose of the Davidsbund, whose name refers to King David of the Bible, was to combat the Philistines of that day - in other words, those with mediocre or narrow-minded taste. (4) The group would also fight against the low standards represented by much of the music performed at the time - that which displayed only empty virtuosity.

Two imaginary members of the League play the most prominent role - Florestan and Eusebius. The characters were first mentioned in Schumann's diary in 1831 and made their public appearance in that same year in Schumann's first published review of the Chopin Variations mentioned earlier. (5) The following passage is quoted in virtually all the Schumann sources. The source here is Oliver Strunk's Source Readings in Music History:

Not long ago Eusebius stole quietly in through the door. You know the ironic smile on his pale face with which he seeks to arouse our expectations. I was sitting at the piano with Florestan, who, as you know, is one of those rare men of music who foresee, as it were, all coming, novel, or extraordinary things. None the less there was a surprise in store for him today. With the words "Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!" Eusebius placed a piece of music on the stand. (6)

The genius is Chopin, and the review continues in much the same tone, reading more like Romantic literature than a music critique.

Eusebius, the dreamer, is poetic and quiet. Florestan is just the opposite, temperamental, impetuous, and wild. The following excerpts from the Neue Zeitschrift, again drawn from Strunk, should provide a glimpse into the nature of their personalities. First, from a review of a variety of dance pieces:

"Should they do so none the less," Eusebius interrupted, "when they come to the trio, he ought to say to his partner-Davidsbündler, 'How simple and how kind you are!' and, in the second part, it would be well if she were to drop her bouquet, to be picked up in flying past and rewarded with a grateful glance."

All this, however, was expressed more in Euseb's bearing and in the music than in anything he actually said. Florestan only tossed his head from time to time, especially at the third polonaise, most brilliant and filled with sounds of horn and violin. (7)

The next is from a review entitled "Florestan's Shrove Tuesday Address Delivered After A Performance of Beethoven's Last Symphony."

Florestan climbed on to the piano and spoke as follows:

Assembled Davidsbündler, that is youths and men who are to slay the Philistines, musical and otherwise, especially the tallest ones�

I am never overenthusiastic, best of friends! The truth is, I know the symphony better than I know myself. I shall not waste a word on it. After it, anything I could say would be as dull as ditch water, Davidsbündler. (8)

These are the personalities, but who are these two? They are actually two sides of Schumann's own personality, as he admits, and are very likely influenced as well by the two brothers Walt and Vult from Jean Paul's novel Flegeljahre. The novel's final scenes, admired by Schumann, focus on the continuing conflicts and competition between the idealism of Walt and the abrupt sarcasm of Vult, and a masked ball with a kaleidoscope of costumed dancers, switched identities, declarations of love, despair, and dreams - all common fare for this period. There is no doubt about Schumann's fascination with the Romantic writers Jean Paul and E.T.A. Hoffmann, who along with other German writers were interested in the idea of the alter ego, expressed as the Doppelgänger. (9) Suddenly, Florestan and Eusebius were everywhere! Schumann published both his Davidsbündlertänze and the Sonata op. 11 under the names of Florestan and Eusebius. Friends did the same, as Jensen comments. "Stephen Heller dedicated his Rondo-Scherzo op. 8 to Florestan and Eusebius. Franz Otto's Phalènes op. 15 was dedicated to them as well. In 1840, a chapter in Julius Becker's novel The New Romanticists was entitled 'Florestan and Eusebius'". (10)

The League of David had other members as well - some real, some fictitious. Some of those representing real people had pseudonyms. Friedrich Wieck became Master Raro, Clara was Cilia, Heinrich Dorn the Music Director. Many of the contributors to the journal even used pseudonyms or numbers to sign their articles. Like the real circle of Schumann's friends, the League of David discussed performances, works, new composers, and the arts, and to that end, the members had particular roles. Eusebius tended to highlight the positive, Florestan the more critical side. Master Raro often mediated between the two, offering a balanced viewpoint. The name Raro, as many authors suggest, was probably a combination of the names Clara and Robert, thus ClaRARObert. Given Schumann's love of word puzzles, this is very likely. The journalistic approach worked wonderfully, and for three years beginning in 1834, members of the League appeared often. No mention of them occurs in 1840 or 1841, and Florestan made the final appearance in 1842. (11) By then, Schumann's compositional style had also altered. And now, the words of the composer in a letter to his friend Dorn to conclude this section.

The 'Davidsbund', as you have known for a long time, is only a romantic creation of the mind. Mozart was once as prominent a member as Berlioz is today, or as you yourself are, without there being an actual certificate of membership. Florestan and Eusebius represent my double nature, the two sides of which I seek to fuse together, like Raro. Behind some of the other masks there lie real people, and much in the life of the Bündler is drawn from reality. (12)

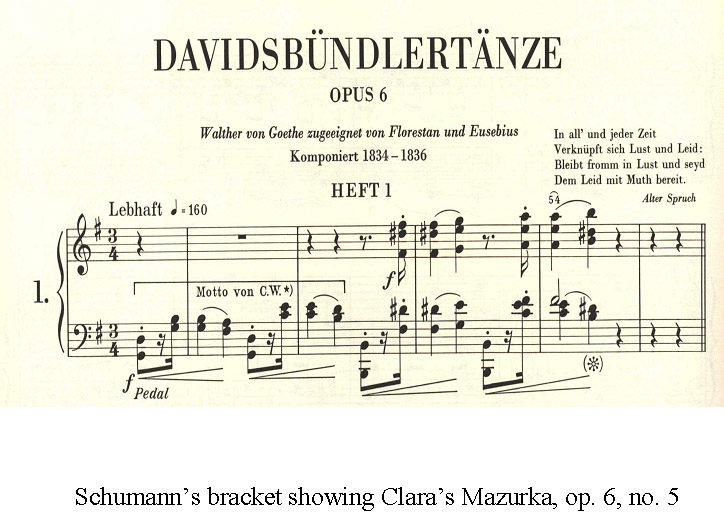

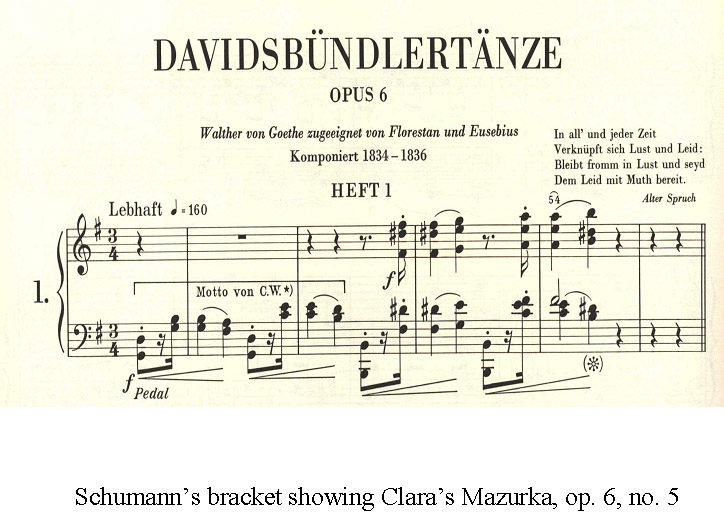

Florestan and Eusebius were not only to be found in the pages of the Neue Zeitschrift, however. They play a prominent role in Schumann's compositional scores of the 1830s. In Carnaval, completed in 1835, the fifth and sixth pieces in the series of short vignettes in which every piece is given a title, are Eusebius and Florestan. Listen to these short excerpts from the pieces. (AUDIO #2) Who else can the first be other than the dreamy, poetic Eusebius, and the second, none but the wildly impetuous Florestan! A second example, and my primary performance piece for this evening, is the Davidsbündlertänze, composed in 1837, and dedicated to Walther von Goethe by Florestan and Eusebius. Each of the eighteen short pieces is designated with an F. (for Florestan), an E. (for Eusebius), or an F. and E. at the end of the piece, and as expected, the moods alternate from gentle and poignant to quick and with good humor. Two examples, the opening piece in the second part, marked F., followed by the second piece marked, E., may be heard in the final audio links.

Now that I have briefly discussed the Davidsbündler, the second half of my title remains - Progressive Romanticism. The designation is really my own, and by it I mean the forward-looking originality that one discovers so frequently when studying Schumann's scores. Many works were still not widely known by the early 1840s, and audiences often considered them difficult to understand. Schumann never composed the sorts of pieces, virtuosic fantasies or variations on favorite popular or operatic tunes, that would have guaranteed quick success. (13) In addition, a permanent injury to his hand that may have appeared as early as 1830 prevented him from following the usual practice of the day - performing and thus promoting his own works in concert. Clara certainly played some of the popular pieces quite frequently in her concerts, along with Robert's works, and although she remained the strongest supporter of Robert throughout his life, even she complained in a letter of 1839, and quoted by Newcomb in his chapter in Nineteenth Century Piano Music:

Listen Robert, won't you for once compose something brilliant, easily understandable, and something without titles, something that is a complete, coherent piece, not too long and not too short? I would so love to have something of yours to play in concerts, something written for an audience. Admittedly, that is degrading for a genius, but politics demands it now; once one has given the public something that it understands, then one can also put something a bit more difficult before it. (14)

One learns much from two contemporary sources from the mid-1840s about early opinions of Schumann's works. In a review published in 1844 in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, Carl Koßmaly speaks first of the originality found in Schumann's works and that, though of artistic worth, they "have become known and recognized only among a small, albeit select and artistically knowledgeable, circle". (15) In spite of citing the difficulty of many of the early works and critiquing the style that seeks too much after the newest Romantic effects, perhaps most telling is the end of Koßmaly's article:

Schumann's piano compositions must be counted among the most remarkable, significant artistic phenomena of our day, that they are characterized through and through by a great nobility of effort and incorporate many seeds of a new era.

Like everything profound and skillful, like everything serious and deeply personal, they, too, will make their way to the general public only gradually and with effort, and will all the more certainly exercise a lasting influence on the entire direction of composition and on musical thought in particular. (16)

The second source, Franz Brendel, in an article published in 1845, says much the same thing, listing the reasons why the works have remained so little known. One revealing reason discussed in Anthony Newcomb's chapter on Schumann and the Marketplace is this: "only a longer acquaintanceship will reveal their tiefere Geist. At the outset, before one conquers the technical difficulties, everything is completely bewildering. This is an important matter, says Brendel, for he knows from experience that many pianists give up on the pieces after the first reading". (17) I would venture to say that for many musicians, this remains true today!

I would now like to examine some of the specific musical characteristics that belong to Schumann's vocabulary. First, from the earliest works on, allusion and symbolism take on a prominent role. The use of quotation in the scores may be both musical and literary. In the case of musical allusions or even direct quotation, the sources may be historical style periods, as in Schumann's fascination with the counterpoint and fugues of Bach, or the sources may be Schumann's contemporaries or even himself. As R. Larry Todd discusses in his essay "On Quotation in Schumann's Music," (18) the contemporary and self-quotes tend to be the most difficult to deal with. How much should be read into the analysis of, for example, a similar bass line? How much is a hidden quotation, and how much is merely a surface similarity? At times there is no question, as in the opening piece of the Davidsbündlertänze, where Schumann tells us directly that his source is Clara Wieck.

In the case of literary allusion, the use of both titles and programmatic elements are of primary importance. Program music in the Romantic era means the use of extra-musical associations - objects, people, a story line, a place, etc. - as being important to the understanding of the music itself. The program may be explicit, as in the case of Berlioz' Symphonie fantastique, where the composer both tells us the story in words, as well as in the depiction of the events through the writing of the music. In other examples, the program is more implicit, a title that suggests rather than explains. Schumann's writing is of the implicit type. He made frequent use of titles, but was reluctant to assign too much meaning to the title itself. As Jensen says, "In selecting a title, he attempted to direct the listener with greater precision to the program (if present) or the soul-state intended for the piece." (19) In many cases, Schumann never revealed the source of the title, and he sometimes claimed that the titles were assigned after the music was composed, accurate in many cases, but not all!

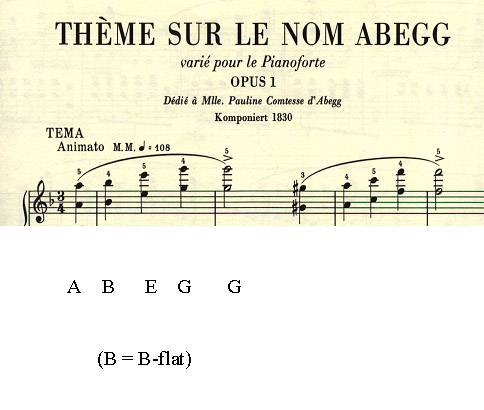

Here are a few brief examples of other types of symbolism, based in part on Schumann's great love of puzzles and word play. His first published composition, the Variations on the Name Abegg, is based on his acquaintance Meta Abegg, who in the dedication is fictionalized into the Countess Pauline von Abegg. Here we see again the composer who chooses not to write variations on a famous opera tune, but on the name Abegg!

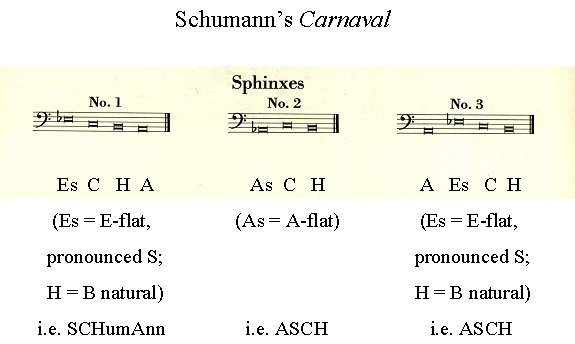

From Carnaval comes the famous movement "Sphinxes." Hidden away in the middle of the piece are these three motives, used in the construction of the material of the entire work, germ ideas derived from the musical letters in Schumann's name and from the residential town (Asch) of Ernestine von Fricken, to whom Robert was engaged for a short time.

Obviously, the performer must have some grasp of these symbols and allusions to begin to understand the music.

The second musical characteristic is the quickly changing nature of the music itself. Quickly changing with respect to both harmony and mood, in many cases. Sometimes the changes appear abrupt to the listener, since they are so unexpected. The well-known composer Hummel points to this trait in a letter to Schumann on the Abegg Variations.

I am delighted at your lively talent. The only thing I might draw attention to is an occasional over-rapid change of harmony. Also you seem to surrender yourself perhaps a little too readily to the originality that you undoubtedly possess. I would not like this to become habitual with you, for it would detract from the beauty, the freedom and the clarity of a well-planned composition. (20)

A good example of Schumann's (as well as many Romantic composers') tendency to use both more frequent modulation and movement to more distantly related keys occurs in the first movement of Schumann's Piano Sonata, op. 11. Within a short series of measures, Schumann moves from E-flat minor to C-sharp minor to B minor to A Major!

The third characteristic is the use of inner voices in the texture, adding to not only the beauty of the musical effect, but also to the complexity for the player. The result is often the special sound I find unique to Schumann. His contemporaries, Mendelssohn and Schubert, simply do not write this way. Compare the following two excerpts - first from Song without Words, op. 38, no. 2 by Mendelssohn, and the second from No. 14 of the Davidsbündlertänze. (AUDIO #3) Although the Mendelssohn has rhythmic interest in the accompanying voices, the harmony is simple, and has none of the complexity of the Schumann example.

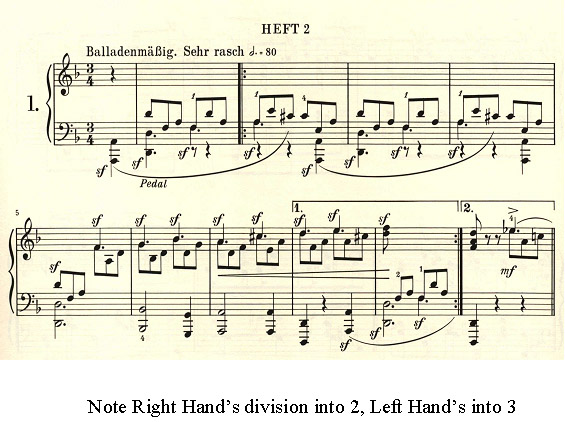

Finally, Schumann's use of rhythm is constantly fascinating. Cross rhythms, misplaced accents, rhythmic patterns out of synch between the hands, harmonic resolutions on unexpected beats, abrupt changes that conflict with the basic pulse - all these are frequent occurrences and are brilliantly discussed by Charles Rosen in his chapter on Schumann in The Romantic Generation. (21) Piece No. 10 from the Davidsbündler is only one example of many in the entire work. One can clearly see the right hand's divisions of two beats containing three eighth notes each and the left hand's three beats divided into twos.

And now, a few final comments on the Davidsbündlertänze as a whole. The eighteen pieces of op. 6, along with Papillons, op. 2, and Carnaval, op. 9, represent some of the finest and most original of Schumann's early works. These are large works, consisting of a series of short, contrasting, and colorful miniatures, and connected to a literary program, however elusive that may be. Other early works do much the same thing, but with fewer, longer movements. All of the works represent some of the best writing in the Romantic genre referred to as character pieces.

When performing early works of Schumann, pianists must make choices regarding performance editions. In the 1850s, Schumann reworked some of the early compositions in second editions. Schumann often smooths out the most abrupt changes and alters the repeats. Not all writers are in agreement about whether the second editions are actual improvements. In the case of op. 6, the inward changes (notes, rhythms, repeat signs, etc.) are minor. Outwardly, though, I view the changes as fairly substantial. The title drops the word tänze, the F. and E. designations disappear altogether, along with the dedication by Florestan and Eusebius to Goethe, as well as miscellaneous comments by Schumann used as headings for the entire work or individual movements. The work was published in two parts, each containing nine pieces. Two of Schumann's headings are most important to highlight. First, in the Appendix is the Alter Spruch (old proverb) found at the beginning of the entire composition, along with the translation given in Maxwell and DeVan's Schumann: Solo Literature. (22) Second, the eighteenth, and last piece, gives Eusebius the final word, with the Maxwell and Devan translation noted in the Appendix: "Ganz zum Überfluß meinte Eusebius noch Folgendes; dabei sprach aber viel Seligkeit aus seinen Augen." (23)

More detailed notes on the pieces of the second part (Heft II) are found in the Appendix. As final illustrations of the original nature of the writing found in the work, recordings of the first two pieces follow. (AUDIO #4) In all the pieces, one finds the richness of texture, harmony, rhythm, and emotion that is part of the genius of Robert Schumann's Romanticism.

| Davidsbündlertänze, op. 6 | Robert Schumann |

| 1810-1856 |

Alter Spruch

| In all' und jeder Zeit | Along the way we go |

| Verknüpft sich Lust und Leid: | In mingled joy and woe: |

| Bleibt fromm in Lust und seyd | In joy, though glad, be grave |

| Dem Leid mit Mut bereit. | In woe, though sad, be brave. |

| (Trans. from Maxwell and DeVan's Schumann: Solo Piano Literature) |

Heft II

Notes on the Pieces

1. Eric Frederick Jensen, Schumann (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 110.

2. Ronald Taylor, Robert Schumann: His Life and Work (New York: Universe Books, 1982), 100.

3. Jensen, 114-115.

4. Jensen, 107.

5. Jensen, 106.

6. Oliver Strunk, comp., Source Readings in Music History: From Classical Antiquity through the Romantic Era (New York: W. W. Norton, 1950), 830.

7. Strunk, 842.

8. Strunk, 832.

9. Taylor, 74.

10. Jensen, 107.

11. Jensen, 112.

12. Taylor, 96.

13. Anthony Newcomb, "Schumann and the Marketplace: From Butterflies to Hausmusik." In Nineteenth-Century Piano Music. Ed. R. Larry Todd (New York: Schirmer Books, 1990), 264.

14. Newcomb, 266.

15. Koßmaly, Carl, "On Robert Schumann's Piano Compositions (1844)." Trans. Susan Gillespie. IN Schumann and His World, ed. R. Larry Todd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 305.

16. Koßmaly, 315.

17. Newcomb, 268.

18. R. Larry Todd, "On Quotation in Schumann's Music." In Schumann and His World. Ed. R. Larry Todd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

19. Jensen, 142.

20. Taylor, 75.

21. Charles Rosen, The Romantic Generation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

22. Carolyn Maxwell and William DeVan, Schumann Solo Piano Literature: A Comprehensive Guide: Annotated and Evaluated with Thematics (Boulder: Maxwell Music Evaluation Books, 1984), 32.

23. Maxwell and DeVan, 42.