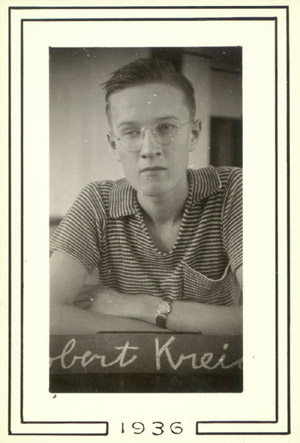

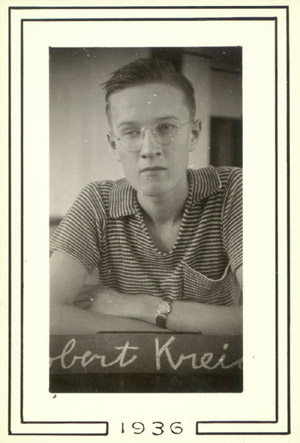

Robert S. Kreider, 1936

September 2003

vol. 58 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2003

vol. 58 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

Robert Kreider of North Newton, Kansas, is an accomplished writer, scholar, leader, journaler, chronicler, traveler.

I have crossed the mystic border. I've left the earth. I've entered

Wonderland. Though I am still east of the geographical center of the

United States, in every spiritual sense I am in the West. This morning I

passed the stone mile-post that marks the beginning of Kansas.

Vachel Lindsay, Adventures While Preaching the Gospel of Beauty, 1928

You show me the path of life.

In your presence there is fullness of joy;

in your right hand are pleasures for evermore.

Psalm 16:1

Robert S. Kreider, 1936

In August 1935 after packing all our possessions into a moving van, Dad left by train for the triennial gathering of the Mennonite General Conference in California. Gerald, Mother, and I drove west in our new Ford V-8 for stops in Dakota and Sterling en route to Kansas. At Dakota we saw 81-year-old Grandpa Shoemaker for the last time. Leaving our cherished Lincoln Highway, U.S. 30, at Davenport, Iowa, we angled southwest toward Kansas. Near Independence, Missouri, we were overnight guests of J. E. and Mamie Hartzler on his ancestral farm. J. E., who did well on the lecture circuits, owned not only this farm but additional ones in Indiana. When we crossed the border into Kansas, all three of us were entering Kansas for the first time. Driving west from Kansas City on U.S. 50 along the Santa Fe tracks we found a new world spread out before us of limitless space, wide horizons, and small towns with towering white elevators. Big sky country--this was the West. William Allen White's Emporia, Cottonwood Falls, Flint Hills to the south where near Matfield Green Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne had recently crashed in an airplane; Walton and grain elevators; and then Newton and more elevators. We approached Newton (no North Newton then) with high anticipation.

This was the West and, yet, where does the West begin? Our late friend Jim Bixel, who lived in Ohio, would don his broad-brimmed western hat when he crossed the Mississippi driving west. He insisted, "The Mississippi, that's where the West begins." For Vachel Lindsay it was the Kansas border. For William Least Heat Moon in PrairyErth it is Chase County and the Flint Hills of Kansas. I think of the wide-horizon West beginning with the High Plains a hundred miles west of Newton at Great Bend on the Arkansas River.

Aerial view of Bethel College, ca. 1937, looking northeast.

The Kreider house is at the lower right, the corner of

Minnesota and 25th streets.

In anticipation of our move, I had studied the illustrated brochures published by Bethel College that presented the campus as a shaded garden spot. President Ed. G. and Hazel Kaufman had talked up the college, its new faculty, curricular innovations, expanding student body--a college of great expectations. We were eager to see our new home and this college on the make. We drove on to the campus on a hot day about the same time Dad arrived from California on the Santa Fe. But no garden spot was Bethel College. Kansas in 1935 was still in the throes of a three-year drought. The campus was dry, brown, and dusty, with temperatures hovering around 100 degrees. Only one paved street, College Avenue, curved through the center of the campus. Dominated by the big limestone Administration Building, the rest of the campus had a look of improvisation, a tentative, a patchwork feel, with renovation projects on many sites, utility ditches being dug, slashes of raw earth, old railway box cars and interurban cars waiting to be installed as campus structures. The house we would be living in on 25th Street, like some other residences, had just been moved to the campus from Newton, and no work had been done yet on grading and landscaping. More raw earth. The street in front of the house was unpaved, a deep ditch between property and street. When rains finally came, we parked our car a block away on paved College Avenue rather than risk sliding into the ditch on our dirt street. South across the street were vacant lots dotted with clumps of cactus. It felt like a frontier town, throbbing with energy, bustling with activity, but with none of the lush, sylvan tranquility of Bluffton College on the Little Riley.

Edmund G. Kaufman in 1934

Despite this mining camp-aura, we delighted in the place. Immediately we received invitations for meals from the Kaufmans, J. F. and Helena Moyer, E. L. and Eva Harshbarger, and more. We met our immediate neighbors and their families: Dean P.S. and Helen Goertz; Walter Hohmann, organist and choir director, and his wife Elsbeth; Uncle Davy Richert, deaf math professor, and his wife Edith; Dr. Pettis, a dentist; Paul Baumgartner, a high school industrial arts teacher and his wife Anna. On the corner of College Avenue lived ailing J. W. Kliewer, second president of the College, who had roots in the college beginnings fifty years before and even beyond that, to the school at nearby Halstead.1 Within a few days I had a campus job earning 20 cents an hour helping dig a ditch north of the Administration Building to the newly-built college dairy barn and next to it a residence, Green Gables, a house also moved from town. There on the first morning, as we were working with pick and shovel, president Kaufman came to inspect our work. He stepped into the trench to take one of our shovels to show us how to increase our productivity. For the first time I heard grumblings from student workers about a president "trying to run everything, even buildings and grounds." And we heard mutterings from faculty members who saw the president as a hard task master. One major complaint was the pressure he applied to impoverished and aging faculty members to go off to graduate school to obtain Ph.D. degrees. Bethel College, once a distant shining image, now had its shadow lines which gave it more three-dimensional authenticity.

My parents were pleased to renew their friendship with the Kaufmans. Hosted frequently in their home, I listened in on the adult conversations, fascinated when Kaufman described all the different kinds of Mennonites living in the area: Swiss, South Germans, Low Germans, West Prussians, Polish, Galicians, Volhynian Swiss, Pennsylvania Dutch Old Mennonites, and Amish. Here was a Mennonite diversity we had not known in Ohio, Indiana, or Illinois: each with different histories, dialects, food systems, worship practices, and patterns of church government. Later I would learn that no where else in the Mennonite world was there such a concentration of historic Mennonite ethnic diversity (eight different sub-groups) as here in this South Central Kansas area. For the first time I learned of Mennonite groups I had not heard of in Ohio: the conservative Holdeman (Church of God in Christ, Mennonite) and the Mennonite Brethren, with their college thirty miles away at Hillsboro. The talk sometimes turned to church politics, which seemed to pack the drama and intrigue of New Deal Washington. Kaufman commented freely on the power brokers, the movers and doers, the wealthy families. We also heard stories of that year's dust storms and the big one on Black Sunday, April 14, when the noonday sky was dark like night.

I was engrossed by the upbeat vitality of the campus. Everywhere renovations were underway: Science Hall basement converted into classrooms, offices, and space for a Linotype and printing press; conversion of Elm Cottage into a health center; a college dairy that supplied student jobs and milk for the campus; improvements in the Administration Building; additional apartments squeezed out of existing residences. We were told that Elm Cottage, Western Home (a men's dormitory), and the Dining Hall--all frame buildings--had, forty years before, been moved fifteen miles across the prairie from Bethel's predecessor school at Halstead. People spoke enthusiastically about the college choir that was just then returning from a sweeping tour to the West Coast, including a concert before 3,000 at the Upland conference. I soon became impressed with Kaufman's driving energy, his explosive speaking style, his provocative weekly chapel talks, his Sunday School teaching full of illustrations from his China mission experience, and his role as an adult authority figure against whom one could pit youthful rebelliousness.

Along with the everywhere-present, dynamic Kaufman, I was impressed by young Willis Rich, the assistant to the president, a man with a hundred ideas and eternally positive and exuberant. Out of his office poured promotional brochures, new programs slogans ("Bethel College--where good friends meet at the crossroads of the nation"), Bethel logos on ink blotters, and dozens more. Rich was the first to embody for me the image of the new man of the entrepreneurial world, the PR man. Also new on campus that fall was another bright young faculty member, Benny Bargen, brother to Mrs. J. S. Schultz of Bluffton. He, too, was bursting with ideas and energy. Bargen, who because of polio walked with crutches, nonetheless strode the campus at top speed. Teaching business and secretarial courses, he introduced on campus a wide range of new office procedures as our own Mr. Efficiency Expert. In the first days I went to see Jesse Loganbill about a campus job. Like Bargen, he was a victim of polio, a hearty, friendly man with a crushing handshake. With several PhDs added to the faculty that fall, we heard much talk of trying again for North Central Association accreditation. Giving the college a churchly presence were a number of faculty and staff who had been ministers or missionaries: Kaufman and Goertz, both former missionaries in China; Abram Warkentin, pastor of Newton First Mennonite Church, an immigrant from Russia who taught German and supervised a small Mennonite historical library and archives; J. J. Voth, industrial arts and pastor of the Gnadenberg congregation; J. M. Regier, church relations; Gerhard Friesen, manager of the dairy; J. F. Moyer, treasurer; my father A. E. Kreider, Bible; soon thereafter, Sam Goering, a former missionary in China; perhaps more.

Not so long ago when I reviewed these impressions with a college classmate, I discovered that he had a radically different memory of his first encounter with the campus. Coming from a good school system in Reedley, California, he remembers Bethel College as ill-equipped, dull, lethargic, and staffed with mediocrity. Differences in the eyes of the beholder.

That September, Bethel's enrollment hit a new high: 314. We had 136 in our freshman class, the biggest one ever and almost double my high school class. For class officers we elected three Newton students: Walter Claassen, later a Newton banker, president of our class, and to the student council, Margaret Regier (Rich) and Billy Thompson, later to be Stated Clerk of the Presbyterian Church in the United States. Just like I had felt four years before, I was a bit intimidated by all the student talent around me. Everyone looked so mature. The men on the football squad impressed me as fearsomely masculine. Many of my freshman classmates were in their twenties, having delayed college studies in those lean Depression years. Some had been teaching one-room school for several years on one- and two-year certificates. In those years one could teach in Kansas with only thirty or sixty hours of college credit. In their minimal wardrobes one observed an equity of poverty. Some students, eking out a college education with limited funds, prepared their own meals in their rooms, men in the White House and women in Carnegie Hall. Those two residence halls looked unsightly in wintertime, with improvised refrigerator boxes protruding from window sills. I lived at home, only a five-minute dash from house to classroom. In this adult world I, at 16, didn't quite qualify as a person of maturity. I needed to shave, maybe, only once a week. And so in my youthfulness and timidity, I dug in, hit the books, and sought to be a scholar. Meanwhile, I was beginning to feel good about my late spurt of growth: that summer I passed the six-foot mark.

Along with other academic innovations, Bethel had introduced new courses in general education. One was a dubiously concocted course combining psychology and composition. In one part we were introduced by P. E. Shellenberg to a behavioristic stimulus-equals-response psychology, which seemed rather mechanistic. The best part of the integrated course was the requirement to write three papers, one an autobiography. Although I had received an A on my life story, when I reread it years later I discarded it as embarrassingly juvenile. In the second paper I wrote a biographical sketch of Leo Tolstoy that gave me a peek into the remarkable company of Russian writers. Best of all, for the third paper I had the opportunity to interview the poet Edwin Markham, who was a campus speaker and our house guest. A man of simple tastes, he had come from California by train, coach class. To be able to interview the author of "The Man with a Hoe" was a special privilege. I remember a group of upper-class women from town coming to our house to meet this famous American poet and to ask him some inane questions.

The single most important course in my college career came that first semester: History of Civilization, taught by a master teacher, Dr. E. L. Harshbarger, then just thirty-five. He was a Bluffton College alumnus and had taught earlier at Bluffton High School. He had traveled to Europe, then a rarity, and enthralled us with direct-from-the-front reporting on sinister forces being unleashed in the world: Hitler and Hirohito, Mussolini and Franco. For the first time in my schooling, here was a course without a textbook, but with a syllabus that called for us to read books on reserve and others from the library stacks. With his sweeping overview of the rise and fall of cultures and civilizations, Harshbarger hooked me on history. He was gifted in portraying the big picture: trends, cultures, empires, epochs, context, the interconnectedness of events. Two earlier career dreams--architecture and forestry--began to fade away, displaced now by history. I have found in my files fifteen pages of outline notes, including two pages of a time line, written in preparation for the final exam. In it appear patterns of organization that characterize my study methods to this day.

Through Harshbarger's course, I was led to spend many hours in the library, which was then on the main floor of the Administration Building. It was no place to study in the evenings because it was packed with males coming to meet and females coming to be met. Leona Krehbiel, who administered a tidy library, patrolled the place with a withering eye. I discovered in the periodical area a shelf of new books on international relations, continuously augmented by others from the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. Included were captivating books by foreign correspondents: John Gunther's Inside Europe, William Chamberlain's Russia's Iron Age, Eugene Lyon's Assignment in Utopia. A comparatively slow reader, I skimmed some books and I savored some line by line. As I dreamed of careers I began to fantasize about being a foreign correspondent.

Another stimulator to my reading was Dr. John Linscheid, professor of English. Although not very inspiring in the classroom, he loaned me from his personal library that first Christmas a dozen books to read, including Christopher Morley's Parnassus on Wheels, which beckoned me on to more books. A wonderful Christmas--a book a day! About that time I read with intense interest Lauren Gilfillan's I Went to Pit College, her story as a college student in the depth of the Depression working in the coal mines. I began to read the New Republic and became a fan of the columnist Heywood Broun. My concern for the injustices of society, still quite academically detached, was intensifying. Not liking the way society was functioning, I was beginning to think of better ways of putting the world together. I guess I was a child of the enlightenment with a visceral confidence in the possibilities of human and societal progress; I had yet to experience the bruising, bloodying lessons of war and institutional pathology.

I was impressed how Dad and Mother, although newcomers, were being warmly accepted into the community. Mother was soon teaching a Sunday School class for young married women, some of them daughters of the town's "best families." That October she was invited to address the Western District Women's Mission Conference on her vision for the role of women in the church. At Upland, Dad had been elected to a nine-year term on the Foreign Mission Board, just four years after he had left the Old Mennonite Church. Almost every Sunday he seemed to be called to preach at one of the area churches, one being the ordination service at First Mennonite Church in Newton for missionary S. F. Pannabecker. My parents appeared to be happy in their new hospitable community.

With Dad serving on the Mission Board, a frequent visitor at our house was P. H. Richert, dour-looking pastor of the Tabor Mennonite Church, a country church north of Newton, who was also secretary of the board. The General Conference had no headquarters in those days. Richert appeared to keep the board files in a brief case that he brought with him on his visits. In communicating with the board, he often sent letters as a round-robin, each member adding his comment and passing it on to the next. On several occasions I went with Dad when he spoke in churches. I recall how I was struck by the Old World appearance of the elderly--simple black dresses and black suits--"plain people," even with no written rules prescribing plain dress. Although Dad always spoke in English, German was still much used in preaching and worship. When we came to Newton, I began reading the Mennonite Weekly Review, then a four-page paper. I was intrigued that in the obituary notices I found so many who were listed as having been born in West Prussia, Poland, or Russia. We had moved into a community where memories of an immigrant past still clung to the people--a touch of Willa Cather's O Pioneers! Decades later when General Conference and Old Mennonites were struggling with the effort to integrate, it was difficult to help Old Mennonites, with their plain dress heritage, to recognize and appreciate that General Conference people were traditionally very simple and plain in their ways, but without codified dress restrictions.

We had left Bluffton, a town of 2,000 where we walked to everything: store, church, school. Living a mile north of Newton we needed a car to go shopping. North Newton, not yet incorporated, had no business enterprises, only a post office--Bethel College, Kansas--and that in the basement of the Administration Building. I found it exciting to live on the edge of a city of more than 15,000--a division point on the Santa Fe railroad with thirty passenger trains a day going east and west, all stopping at Newton, passengers often getting off for a meal break in the fabled Fred Harvey Restaurant. Sensing we were almost rubbing shoulders with celebrities, the town paper frequently reported movie stars stepping off a Super Chief train that halted for ten or fifteen minutes at the Santa Fe station: Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, Myrna Loy, and such. One heard a lot of railroad talk in Amos' basement barber shop under the Kansas State Bank. Amos had a high squeaky voice--the result, as it was told, of a castration by an angry posse of husbands who didn't like his extra-marital roamings. A frequent topic of barbershop debate was the steam engine versus the diesel; in 1935 it was still an open question as to which would be the winner.

Where Bluffton had only one town center, Newton's downtown was dotted with more than a dozen scattered neighborhood groceries and occasional filling stations. Each grocery served a clientele within easy walking distance. It was safe to send one's youngster off to the neighborhood store to buy a dozen eggs or a pound of sugar. The grocer was a family friend. Today, not one of those "mom and pop" operations survives. You get in a car and drive several miles to the Dillons supermarket to shop.

The number one topic of conversation in Newton, especially with the approach of November, was high school basketball. Year after year the Newton Railroaders were contenders in the state tournament, often state champions. No blacks played on the team: Coach Frank Lindley, who was also the high school principal, disapproved of black skin touching white skin. Not far away was Halstead, the hometown of Adolph Roup, who was of Mennonite birth and became a legendary basketball coach at Kentucky. In the nearby oil town of McPherson was the nationally famous semi-pro basketball team, the Oilers, that moved to Oklahoma to become the Bartlesville Oilers, then to Indiana to become the Fort Wayne Oilers and on to Michigan to be the Detroit Oilers. Those were the days before the advent of NBA pro basketball and Michael Jordan. In the spring of 1936 James Naismith, the originator of basketball, came to campus to speak at Bethel's annual Buffalo Barbecue, to tell the story of how at Springfield YMCA College in Massachusetts he nailed peach baskets at opposite ends of a playing floor and inaugurated a game that has swept the world.

Early on, Mennonites made inroads into the business life of Newton. The three flour mills had been established by Mennonites: Warkentin, Claassen, and Goerz. The two major banks were owned by the Claassens and the Sudermans. The largest of two hospitals was Mennonite governed, Bethel Deaconess Hospital. Up and down Main Street were a number of Mennonite-owned businesses: those of Rich, Regier, Ensz, and more. Despite this firmly planted Mennonite presence in town, people talked of underlying town-gown tensions--memories lingering from the World War of businesses daubed with yellow paint and harassment of German-speaking, pacifist Mennonites.

Still operating in 1935 was a rural trolley line, the Arkansas Valley Interurban, linking Newton with Halstead, Sedgwick, and Wichita, and making connections beyond. We were told that once a spur came all the way to the Bethel campus. The Newton airport was then on the northern edge of town, bounded on the north by old U.S. 81 (now a triangular area of residences, a small shopping plaza, and Faith Mennonite Church). On this airfield I was introduced to a local diversion of chasing fleeing jackrabbits at night, in a car with headlights on. These prairie creatures are now rarely to be seen. In retrospect, a rather sadistic sport. That first fall I had my first airplane ride, a loop over Newton in a Ford Tri-motor, the price 50 cents a ride. We learned that U.S. 81 was also a "Mennonite highway" that stretched from Winnipeg in the north down to Freeman, South Dakota, on to Henderson, Nebraska and then to McPherson, Moundridge, Hesston and Newton in Kansas, on to the first Mennonite mission station at El Reno in Oklahoma, and beyond to distant Belize in Central America, the place of settlement for Old Colony Mennonites fleeing modernity and English language schools in Manitoba. East-West U.S. 50 and North-South U.S. 81 were the two Mennonite highways.

Just off the east corner of the airport on Main Street Henry Unruh operated a busy gas station where he sold eight gallons for a dollar. Another good buy in Newton could be found at Young's Lunch, next door to the Methodist Church on Main Street. There you could purchase six hamburgers for a quarter. At Young's lunch I was introduced for the first time to chili, Mexican cuisine then making inroads.

I was shocked that Newton displayed open race prejudice. Although there was a black community of 500 in Newton, Jim Crow patterns prevailed. Blacks were confined to a Jim Crow section at the back of the theater and were denied access to restaurants, the swimming pool, and barber shops. No Negroes clerked in stores. One restaurant, however, did serve blacks: the Fred Harvey House at the Santa Fe station. Racial segregation persisted into the 1950s. Adding to the cross-cultural variety, Newton had a Mexican-American community of several hundred, many of the men working on the railroad.

To refresh my memory of those distant times, I turned to the August and September 1935 issues of the Evening Kansan Republican and the Mennonite Weekly Review. Wheat in Central Kansas that drought year averaged 10 bushels to the acre and was selling for 86 cents a bushel. The big news was the air crash and death in Alaska of aviator Wiley Post and humorist Will Rogers. Satchel Paige pitched a Bismarck, North Dakota, baseball team (a rare mixed Negro-white team) to a national semi-pro championship. Shirley Temple could be seen in "Curly Top" at the Regent Theater. Downtown Newton then had three movie theaters, two of them showing mostly low-budget cowboy films. In August President Roosevelt signed the Social Security bill. A half-million young men were in Civilian Conservation Corps camps. The U.S. military budget had risen to $806 million--$6.35 per man, woman and child. The week we arrived in Newton, Mrs. J. C. Mack, editor of the Kansan, wrote a blistering attack on Roosevelt and the New Deal, using harsh words like: "revengeful penalties upon wealth," "economic quackeries," "brazen contempt for the Constitution," "impudent dictatorial rule," "national bankruptcy and political chaos." This hit me, a cheerleader for the New Deal, as a shockingly discordant voice.

In the region around Newton were colleges of the three historic peace churches: McPherson College in McPherson--Church of the Brethren, Friends University in Wichita--Society of Friends, and three Mennonite colleges: Bethel; Hesston College, an Old Mennonite junior college at nearby Hesston; and Tabor College, thirty miles northeast at Hillsboro, a Mennonite Brethren College. I picked up some sense of the Mennonite mosaic in the area: Old Mennonites around Hesston, Old Order Amish west at Yoder, Volhynian Swiss west sixteen miles beyond Moundridge, South Germans at Halstead and Moundridge, Galicians southwest of Hutchinson at Arlington, Mennonite Brethren around Hillsboro and Buhler, Holdeman scattered about in several areas, West Prussians east of Newton toward Elbing and Whitewater, an island of Swiss at Whitewater, an island of Polish east of Newton and, all around us, the largest group--Low Germans, those who migrated in the 1870s from South Russia having come in stages, over the centuries, from the Low Countries via the Vistula delta region of West Prussia.2 That first year in Kansas, I was surprised and pleased how quickly came a sense of place, a feeling of belonging.

Beginning in 1935 and for the next four years the campus was the center of my world. The town of Newton played a less central role than the village of Bluffton had earlier, in part because I had not attended Newton public schools. Given my boyhood interest in woods and stream, I did not immediately transfer my affections to the Kansas prairie. It took some years before I became fascinated with Kansas wheat culture. In retrospect I wish I had spent a summer working with a crew following the wheat harvest. I knew nothing of the charms of the Flint Hills, an hour's drive to the east with herds of cattle grazing on a hundred hills. Nor did I know of Cheyenne Bottoms and Quivera wetlands sixty miles to the west, refueling stops for millions of birds in their international north-south migrations. In those days the campus was all-absorbing.

Ahead of me were upperclassmen to admire from a distance: Ray Guy, a commuter from Newton and top debater; Reinhold Weinbrunner, the epitome of a scholar, who logged more hours in the library than anyone else, later to become editor of The Mennonite; a number of rugged football players, some of whom appeared to be serious students. I was drawn to Ted Voth, son of a Mennonite Brethren missionary to India, brilliant scholar majoring in physics, debater, varsity tennis player, who was agonizing his senior year whether he should leave science for theological study. Bill Juhnke, a history major, exuded enthusiasm for peace, politics, and Mennonite young people's work. Many industrious students had no support from home and were working their way through college, one being my good friend Karl Baehr, who got up at four in the morning to milk cows at a local dairy. He pursued tenaciously both his studies and extra-curricular activities, where he focused on debate and the Student Christian Movement. A man of moral passion, he stirred the waters with a wee bit too much stridency to suit my taste. Glen Fuller, husband of organ teacher Wilhelmina Bixel Fuller, was an older student who came from a local impoverished family. He was widely read, interested in Indian lore and nature, a thoughtful skeptic, a non-conformist. With this influence as peer models, upperclassmen are important in creating a stimulating academic community, a dimension lacking in a college of commuters or a two-year community college. I never took a course from Benny Bargen, but his upbeat spirit was pervasive on campus. Bubbling with creative talent, he wrote a series of biblical sketches for radio, which during my sophomore year he arranged to have broadcast on Radio KFH Wichita. He tapped several of us to go to Wichita on Saturday mornings to record live these dramatic sketches out of Genesis. Another teacher who meant much to me was Thelma Rinehart, who taught drama and speech. A Methodist outsider who loved the campus, she drew me into taking character parts in several plays and was my adviser on a senior honours course on contemporary drama. For one a bit shy, she offered a welcome touch of affirmation.

Junior class play for 1938, "Attorney for the Defense";

Robert Kreider standing at left

In those days, aspiring to qualify for North Central Association accreditation, Bethel seemed dragging along with PhDs of short tenure, who were added to upgrade the faculty degree profile but were disappointments in the classroom. I grudgingly discovered that I could learn a considerable amount even from less-than-exciting teachers. In a class on the history of philosophy, otherwise prosaic, four of us students prepared for an exam, each taking a particular philosopher--Kant, Hegel, Locke, or Hume--and defending the particular philosopher against critiques from others in the foursome. It was more fun than class and an exhilarating way to enter into the minds of dead philosophers. I owe much to a teacher of biology who helped me narrow the field of my career choices. I can see him now plodding through his tattered textbook, frayed pages broken from the binding, which he fingered gingerly page by page. The professor seemed tired and without contagious enthusiasm for the subject; he gave us the cells of a leaf but no trees, no forests, no prairie ecosystems. He punctuated his slow-paced lectures with stories about football that drew guffaws from a block of athletes in the class. For me, that course had its merits, as a case study on how not to teach. It also closed the door on forestry as a career possibility. I did enjoy peering through a microscope and sketching what I saw. And my interest in trees was not extinguished.

No teacher inspired me more than Dr. E. L. Harshbarger. A fluent speaker, he had a gift of capturing the sweep of history, the inter-relatedness of disciplines, the big picture. In each course he called for a major term paper, properly documented, which he carefully read and on which he penciled his comments. I worked hard on papers on such topics as the Muckrakers, the Irish struggle for independence, the German Drang nach Osten, British colonial rule in India. I was pleased when he was pleased. I never thought of writing, nor was I encouraged to write, a paper on a subject related to the Anabaptists or Mennonites. Particularly absorbing for me was Harshbarger's course on Modern Social Movements, where he revealed his enthusiasm for the cooperative movement and the kind of economic and political system described by Marquis Child in Sweden--the Middle Way. I recently found a paper I wrote for the course on Stalin's 1927-38 purges, revealing that I was not at all enchanted with the Soviet model. In addition to teaching in the classroom, Harshbarger was the debate coach. In my freshman year he teamed me with the smoothly articulate Billy Thompson. Harshbarger was masterful in analyzing a debate topic. The best part of debating were the trips with him to tournaments and the opportunity for conversation with this widely-read faculty member. I began to dream of being his colleague on the Bethel faculty.

Bethel College debaters, 1936?; Robert Kreider is 4th from left,

Karl Baehr 3rd from left

Restrained in expressing approbation, Harshbarger never urged me to pursue graduate study in history. Nonetheless, I sensed his unvoiced encouragement. The best accolade received from him came to Dad via Dr. Linscheid. Harshbarger had shown Linscheid with pride a paper I had written. I heard indirectly that he was amused and pleased to learn that he was the only professor to give me a "B," not for that paper but for a reading course in which I was tardy in submitting my reports. At Bluffton College Harshbarger had majored in history under C. Henry Smith, whom, fifteen years later, I would succeed. Harshbarger played a lineman on the Bluffton football team alongside Lloyd Ramseyer, who brought me to the college in 1952.

We intensely admired Dr. Harshbarger for his leadership in peace activities. Lending authority to his words on international affairs was the fact that he had been on a summer tour of Europe led by Sherwood Eddy, the ecumenical leader and social activist. Travelers to Europe were a rarity in those days. Harshbarger was the prime mover in bringing to the campus the Kansas Institute of International Relations, which held week-long conferences in June featuring world authorities in the peace movement. It was a dazzling series of speakers. Eighty-year-old Charles M. Sheldon, author of In His Steps, was the lead-off speaker. Particularly captivating was the reporting of an English journalist, John Emlyn Williams, who arrived direct from Berlin to give eye-witness reporting on Hitler, Mussolini, and the Ethiopian crisis. The star that first year, 1936, was Andrew Cordier, of the Church of the Brethren and a professor at Manchester College, who gave from a pacifist perspective a masterly overview of world events. He later became Deputy Secretary of the United Nations and interim president of Columbia University. The next year, 1937, brought Harvard historian Sidney B. Fay speaking on Europe, Y.T. Wu on China, Samuel Guy Inman on Latin America and, best of all, the gifted English preacher Leyton Richards. I remember his use of the Trinity as an image deep in meaning for peacemaking, this making a puzzling theological concept credible. Bethel offered a rich intellectual diet.

A painful experience was the one time I broke ranks with my admired history teacher and debate coach. When Bethel College received North Central Association accreditation in 1938, Dr. Harshbarger applied and received acceptance for a chapter of Pi Kappa Delta, a national honorary forensic association. Don Smucker, then secretary for the Kansas Institute of International Relations, reported to me that the fraternity had an Africa exclusion clause that would bar from membership my black debate colleague, Aldace Mercomes. Needled to action by Don, I wrote an editorial questioning Bethel's membership in the Jim Crow fraternity, followed by the dreaded task of telling Dr. Harshbarger that I chose not to become a charter member. He responded that he was of the experience-tested conviction that the best way to affect change was to work from inside an organization. I remember a group of debaters coming to seek advice from Dad, who supported me, as to whether they should join or not. Only Aldace and I did not join. It took ten years for the fraternity to drop the Africa-exclusion clause. Change came, less by voices of conscience from within than by the changes in public policy wrought by World War II. I carried away from that experience a lingering sense of prideful rectitude that was certainly injurious to efforts to be humble and downplay it all.

Amos E. Kreider, from 1938 Graymaroon

(Bethel yearbook)

I had known my father as a pastor. Now I observed him as a teacher and as campus pastor. Although I kept my distance from taking Bible courses from him until my junior year, I observed him with heightened respect. I was pleased to see fellow students come to the house to talk with Dad. I sensed he drew the affection of students. As campus pastor he conducted with dignity the daily chapel services, often using poetry in his meditations. We heard many visiting speakers in chapel, including many of the Newton pastors. Most of Newton's pastors had their annual turn to speak in chapel, thus contributing a touch of ecumenical awareness. Chapel services were held in the second floor chapel with its stained glass windows. One flawed moment at the close of chapel was when Dad announced that "Martha Penner will sing and then we shall all pass out." A howl of laughter burst forth, with Dad visibly perplexed as to what had evoked such an outburst. In one of the chapel services I was introduced to premillenial-dispensational theology. Elizabeth Goertz, a missionary from China, came with a large chart to explain in a stumbling fashion a complex system of prophecies outlining the stages of end times, dispensations, the time of rapture, the War of Armageddon. Once a week president Kaufman spoke--his a ragged, stop-and-go style, impulsive, an improvisational eloquence. He ranged over a wide variety of subjects designed to provoke thought and discussion. Sometimes he annoyed, but I listened.

President Kaufman was a major intellectual force in my college experience. He taught a student Sunday School class where I remember him less for his answers than for his questions, less for his declarations of theological belief than for his invitations to further inquiry. He could startle one with his bursts of enthusiasm; sometimes he even shocked his students. A tingle of pedagogical electricity pulsated through his class sessions. His was a stimulating teaching style, but not one I could or would want to replicate. He captivated us with stories from his China mission experience. I enrolled in his senior course, "Basic Christian Convictions," where at the start he asked what our expectations were for the course. I proposed a survey of theological systems--for me, a way of maintaining intellectual detachment. He had other plans. He wanted to engage us in taking a stand: one or two weeks on each basic Christian doctrine, each of us to write an essay on our convictions on the subject. Then he divided us into committees charged with homogenizing the diverse statements into one. That was a hopeless task, with a mix of students from the faith-indifferent and skeptical to those espousing mainstream Protestant theology to a fundamentalist returned missionary to graduates of Bible schools. At that stage I was prepared to respect orthodox Christian doctrines, but not to embrace them.

Kaufman served as an authority figure against whom I could tilt my youthful lance. Hearing him talk about abolishing football, I wrote an editorial in the Bethel Collegian declaring the merits of intercollegiate sports. A situation that particularly enraged me was his appointment of his young secretary, Hulda Schroeder, to be adviser to the Collegian. He instructed us to submit all copy to her before it went to press. Back it came with penciled notations and deletions that were clearly her boss's markings. I exploded with displeasure to her; off she went to tell Miss Rinehart tearfully of our encounter. Thereupon, Miss Rinehart sought me out to rebuke me for my ungallant explosion of anger to Hulda. I thereupon marched into Kaufman's office and declared that using his secretary as a cover for his censorship was intolerable. He caught me off guard by his serene defenselessness and soothed my wrath. With that encounter, presidential censorship ended. Kaufman knew that there was power in the printed word and, called to manage this household of learning, he felt a need to control the student newspaper. Once he called me into his office and encouraged me to think of the ministry. Several times he inquired about my post-college plans and urged me to consider college teaching. Despite the forbidding gruffness of this authority figure, I sensed an affirmation. Years later he asked me to write a forward to his book, Basic Christian Convictions, and at his death, the family invited me to give a tribute at his memorial service.

I found a number of courses outside of history highly stimulating. In Bible study I enjoyed Dad's courses on the Prophets and Acts, and I also appreciated Thelma Rinehart's courses in drama. In my final semester I devoted much time to an absorbing Honors Course, an independent study in which I read several dozen contemporary American and British dramas and wrote a substantial paper which I defended in an oral examination. It is curious to note that, although Mennonite history would later become my area of doctoral concentration, I did not take Dr. Abram Warkentin's highly-regarded course in Mennonite history. I reasoned that I already had a good grasp of that subject. To add PhDs to the faculty, the college had picked up several professors of dubious teaching skills and amusing idiosyncrasies. One was a professor of sociology, who seemed spaced out from this world and who had quirky ideas on family and sex that led us to roll our eyes. A professor of economics, so eager to please, even accepted wrong answers we gave in class by reworking them into right answers. To lend color every campus needs some such characters, but preferably not too many.

As a student I often said that the best part of college was the extracurricular activities. In the 1930s the campus was a closely-knit community with most of us engaged in multiple extracurricular activities. A majority of us had campus jobs. (President Kaufman admired the model of Berea College in Kentucky with its work-study program.) As a freshman I graduated from ditch digging to campus maintenance work. Among other things I assisted a plumber installing toilet facilities in four interurban cars that had been moved onto campus and arranged in a quadrangle known as "Pullman Court." In that depression era, this was recycling before the era of recycling. In the summer of 1936 with its record-breaking heat, I worked as assistant to a paper hanger, a steamy job. Elmer Ediger arrived to succeed me in this role and to go on to a four-year career as the campus paper hanger. Along with paper hanging, I enrolled for piano lessons with professor Hohmann, which I abandoned after a half-dozen lessons and a faltering pattern of practice. For campus employment I later wrote news releases for the publicity office. On the side I sent sports articles to the Topeka Daily Capital, for which I was paid by the column inch. For three years I operated a campus dry-cleaning route for Miller Brothers on East Broadway in Newton. I enjoyed weekly chats with two Miller brothers, both having been high school basketball stars--for me, they offered a window to the town scene. All this, while I was living at home reduced my costs. I recall wearing the same outfit day after day: a heavy, knit, black wool, crew neck sweater and dirty white buck shoes. With scholarships and campus jobs, my parents spent out of pocket only about $300 for my college education. Relieved of the usual financial burdens, I was free in the summers of 1937 and 1938 to apply for significant service and travel experiences.

Except for intercollegiate debate, my freshman year was one of quite focused scholarship. Shy and a bit intimidated by the maturity of my peers, I did no dating. By the end of the year I was developing close friendships with Bob Regier and Esko Loewen. Esko lived on a farm a mile from campus. He had been a big man in drama in high school, a friend of many, and he brought a fun-and-games approach to campus life. By my sophomore year we were co-authoring a light-hearted column for the Bethel Collegian, where our models were newspaper columnist, Odd MacIntire, and Heywood Broun. Bob Regier was a bright math and chemistry major who shared a passion for current events and Time magazine. On standardized tests given to the entire student body when we were sophomores, Bob had the top score in science, books and art, and contemporary affairs. I was ahead of him in history, general culture, and political events. Ours was a friendly rivalry, with Bob usually having the edge. I was attracted to him for his wide-ranging interests and his sharp repartee. Both Bob and I were minister's sons and lived at home. Bob, Esko, and I were often in each other's homes and worked long hours together on the Collegian.

Toward the end of my college career I developed a close friendship with Elmer Ediger. Elmer came from a farm home near Buhler, and probably had to earn every dollar for his college education. He intrigued me for the energy and vision he invested in student organizations, particularly the Student Christian Movement, of which he became president. His curiosity and keen social conscience led him to spend a summer with the School of Living at Suffern, New York, led by a Borsodi and Ralph Templin, with their vision of building pacifist intentional communities. My institution dreaming and building propensities were quickened by association with Elmer. In my lifetime I have known no one with a greater fondness for and resourcefulness in institution-building than Elmer and his and my mentor Orie Miller, executive secretary of MCC. My friendships with Bob, Esko, and Elmer became ones for a lifetime. Now all three men are gone.

And in my junior and senior years there were girl friends (in those days, not "women friends"). In my dating around I experienced annoyance with my too-concerned mother. If I dated someone two or three times, her interest in the friendship escalated, leading her to speak approvingly, encouragingly of that person--thus, magnifying the seriousness of the friendship. That was enough to cool my ardor. I played the field but not too aggressively. Brother Gerald, who was a freshman my senior year, took women much more seriously. His first year he began dating Elinor Krehbiel, whom he would marry at the end of his senior year.

The organizational side of my personality began to emerge in college. I was elected president of both my sophomore and junior class and, in my senior year, president of the Student Council. Yearning for a campus as rich in traditions as Bluffton College, I, together with others, set out to introduce some new events on the Bethel campus. One was the introduction of an all-campus talent night, another enhancing homecoming activities, electing a Homecoming Queen, and calling the football game the "Wheat Bowl." In an unsuccessful effort, we sought to restore to life, with a new format, a yearbook which had slumped to embarrassing quality. Our biggest effort focused on the Bethel Collegian. For some years it had been a Wednesday page in the Newton Kansan Republican and was distributed on campus as a free handout. Appearing on a stage for all the town to see, that public exposure cramped our editorial freedom. As a sophomore, I and the editor of the page went to see rigidly conservative Mrs. Mack, the grumpy editor, and spread before her our plan to give the college page a more attractive format. The answer: a flat "No." The next year we started a campus edited and printed weekly newspaper. Expanded in my senior year into a five-column paper, the Collegian was my number one college passion.

I loved the camaraderie of night sessions in the Collegian room in the basement of Science Hall when a gang of us would edit copy, write headlines, correct proof, and paste up layouts. Also fun were the post-publication sessions when we would sit around dreaming up feature stories, editorial ideas, and questions for the inquiring reporter column. I also enjoyed seeking to woo others into joining us in this new campus enterprise. We experienced some bumpy times, however, such as president Kaufman's aborted effort at censorship. Another was an editorial encounter with grim-faced Dr. J. R. Thierstein, a retired German professor, who lived on campus and edited the denominational periodical, The Mennonite. On the front page of the September 27, 1938, issue Bob Regier and I were incensed to find an editorial by Thierstein entitled, "Is There No Difference?" He criticized Americans who were slandering Nazi Germany by lumping it together with Communist Russia. In comparing Germany with the Soviet Union he wrote, "In Germany Christianity is still treated with reverence and respect." He spoke of how "Communist-Jews . . . were [becoming] masters of the land, the same that they had done in Russia." He cited how in Russia a remnant of Mennonites was being subjected to a policy "to kill, starve or torture them off slowly." He concluded with the question: "Is there no difference?"

Two days later in the Collegian, Regier and I ran an editorial under a linoleum block image of Mars, the god of war, entitled, "There Is No Difference." We called the Thierstein editorial "shocking": "A Christian periodical . . . is treading on very dangerous ground when it seeks to justify National Socialism. . . . We loathe Stalinism as an arch-enemy of democracy and Christianity. . . We sincerely believe that the Nazi dictatorship is evil, even as the Stalinist State". Objecting to his minimizing of Jewish persecution, we wrote that "the treatment of the German Jews is about as cruel and malicious as any race could receive." With that editorial we experienced a surge of righteous self-satisfaction. We were on the side of the angels. This evoked a postcard from Thierstein, who objected to our "tirade": "You parade LOVE. Did love prompt you to write your article and to place at its head that ugly picture of Mars?" Several months later he again was displeased with me, this time for an article I had written about my 1938 summer trip to Europe. He wrote me: "Why say good and nice things about other places visited and, when coming to Germany, in one single statement add more fuel to the fire of hatred against Germany, which the Jewish-Communist controlled Associated Press has succeeded in stirring up so well in America." After another such paragraph, he added conciliatory words, "I know you mean well and I hope you make the same allowance to me." I have no record of responding. I wish I had expressed a kind thought. Thierstein died a few months later.

A variety of events--on and off campus--captured our attention. One was the week when Glenn Cunningham, holder of the world's record in the mile run, came to town to be with his wife, who was giving birth to their first child in the local hospital. Daily he practiced on the college track and on the final day ran a demonstration mile with our classmate Waldo Leisy, ending in a dead heat. In the fall of 1936 we flocked to the Santa Fe station to see President Roosevelt, on the campaign trail, waving to us from the rear platform of the train, Republican-voting Newton not honored with a stop. I represented the college at a mock legislative session in the Topeka State House, an unforgettable memory being a radio broadcast we listened to outside the legislative chamber. We heard King Edward VIII announce his abdication from the British throne to marry "the woman I love." In October 1938 we celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the college with a pageant in Newton's Lindley Hall, Dad as a narrator, I among those in a speaking choir. On a Sunday evening, a group of women in Goerz Hall listening on the radio to Orson Welles's Mercury Theater presentation of "The War of the Worlds" panicked and knelt in fervent prayer. In 1939 the visit and concert of the Bluffton College choir quickened our social life; it led to dates with choir members, whose charms were enhanced by being from a faraway campus. Significant as a sign of progress was the laying of the foundation for Memorial Hall with its gymnasium / auditorium, a project in which many of us students pitched in with volunteer labor. One of my jobs was handling a wheelbarrow carrying concrete for the footers. An exhilarating event, especially for the administration, was Bethel's election in 1938 to accreditation by the North Central Association--the first Mennonite college to achieve that distinction. On a Sunday evening in the spring of 1939 Harold Bender of Goshen College spoke on MCC's emerging program in Europe. I raised my hand to ask the question, "What service is MCC planning for young people?" However, there was no time left to hear my question.

Cornerstone laying for Memorial Hall, Oct. 12, 1938

Throughout college I seemed to have a need to maintain a little distance, but not much, from the faith and church world of my father. I viewed critically the conservative Student Volunteer group on campus--for me, it was too pious, too certain doctrinally. Nominated for offices in the Student Christian Movement, I declined, preferring less confessional activities like Student Council and Collegian. My reading in the realm of faith issues gravitated to books on peace such as A.A. Milne's Peace with Honour, Shidharani's War Without Violence, Richard Gregg's Power of Nonviolence and, especially, Cadoux's The Early Christian Attitude to War. My essays on biblical doctrines for the course on Basic Christian Convictions were bland and guarded. I felt more comfortable in being a closet doubter. Yet I had a margin of acceptability, in as much as I was chosen by the class, which included several ministerial students, to be the student chair person for the course. At the end of the course, upon reading my cautiously minimal, muted statement of my doctrinal views, Dad inquired, "Don't you want to go further?" So gentle was his encouragement to be more declarative in my faith. Meanwhile, Dad, who was asked to find students to fill pulpits in the community, invited me several times to take preaching assignments. This was one of his ways of tapping a faith stream inside of me which I was reluctant to acknowledge.

Our pastor throughout my college career was Jesse Smucker, a Goshen College alumnus friend of my parents, and a classmate of Harold Bender. For him I had great admiration. Harking back to those sunset services at Camp Shipshewana, his sermons drew me with their lyrical, poetic quality. Having been appointed to be usher, my regular attendance was assured. No sleeping in on Sunday mornings during these college years! Ushering was intriguing because it provided insight into the idiosyncrasies of congregation members. Once when the offering was passing between Dr. Thierstein and his wife, the plate fell with a clatter. He turned and glared at his wife, his bald head shaped like a roll-top desk, turning red.

Approaching graduation, my career interests were unsettled. The faculty nominated me for a Rhodes Scholarship. I thought two years in Oxford would be an ideal way of deferring career planning. Following interviews at the University of Kansas with the Rhodes selection committee, I emerged number three when two were chosen to represent Kansas. With the outbreak of war in September, those elected as Rhodes Scholars that year did not go to Oxford. All through my junior and senior years I was casting about in a variety of directions. In one direction I fantasized about travel. Among items saved from those days are several pamphlets I pored over: "Foreign Lands at Stay at Home Prices," "Vagabond Voyages," and "How to get a job on a ship." Just fantasies because with a war looming, this was no time to travel.

Dr. Abram Warkentin alerted several of us that the American Friends Service Committee had negotiated a plan for a small group of college students to be interns with the U.S. embassy in Berlin. Rufus Jones, chair of the American Friends Service Committee and a Haverford College professor, had a hand in these negotiations. Following a flurry of encouraging letters, that plan collapsed. I inquired into scholarships for foreign study, but without success. Our idealism probably triggered by Bender's talk on campus and an address by Rufus Jones at Friends University, a group of us began meeting in early 1939 to explore possibilities for a service program under Mennonite auspices. On March 9, 1939, I drafted a letter, signed by nine more, and sent it to Dr. Harshbarger, chair of the General Conference Peace Committee. The letter said: "We are looking for something to unite the youth in the work of the Kingdom of God. We feel that our Mennonite doctrine of nonresistance is needed in this world. We believe that expression of this doctrine should be made now, in time of peace, as well as during wartime. . . We are aware of the existence of suffering and despair in communities around about us and in war-stricken areas. What would you suggest that we as Mennonite youth do to meet this need and thus express the message of love and nonresistance?" Harshbarger responded appreciatively, and Warkentin, the General Conference member on the MCC Executive Committee, wrote, "It would be very helpful if the Mennonite groups could unite on the type of peace work they could do and the kind of testimony they could give." A concern had been deposited, but I do not recall any significant follow-through. Six months later, Europe was at war.

That spring semester I applied for scholarships in international studies at Harvard, Yale, and the University of Chicago, and in history at the University of Kansas. I was assured admission at each but was offered a scholarship only at KU. I had also applied for a scholarship at Chicago Theological Seminary, affiliated with the University of Chicago. From CTS came a $500 scholarship plus free tuition, a full ride. I took it. I saw it as a good base to probe varied interests at the University of Chicago. President Kaufman had often urged that if one was planning to teach in a church college, a year or more of theological study was excellent preparation. Already I was beginning to envision myself as a college teacher. Scanning the field for a spot on the Bethel faculty, I began to eye covetously a position in economics, where I thought that dear but ineffective Dr. Geeting would not be surviving long on the faculty.

I don't remember who spoke at our commencement service, but I do remember President Kaufman's baccalaureate address on Christian authority. At the time I chafed in his occasional professions of theological orthodoxy, but reading the address a year later, having matured a bit, I thought it was on target and a remarkable product for a harried college president. When the dean announced that I graduated "with highest honors" and with all "A's" except in a two-hour semester course, I felt both pride and embarrassment. For the next couple of days, I experienced a drag of depression. Perhaps it was withdrawal pains from college, but it was also a feeling that my reputation had been inflated in faculty eyes. I wasn't that good a student. I thought that some professors had been entrapped into giving me "A's" against their better judgment, simply because I was considered locked-in as an A student. My mood soon lifted as we set out within a week for a Student Christian Movement conference at Estes Park, Colorado. Throughout my college years, summer vacations were both an extension of learning and good therapy.

On occasions when I was displeased with Bethel College, especially when I was annoyed with president Kaufman, I toyed with fleeing to another college. However, as I compared experiences of friends on other campuses, Bethel looked pretty good. Particularly after studying at the academically respectable University of Chicago, my appreciation for the qualities of the college brightened. I became a Bethel apologist and advocate.

1. An aside note: I have known all of the presidents of Bethel College except the very first one, C. H. Wedel.

2. In recent times I, not a native of the area, have taken dozens of groups on tours of this Mennonite region that extends 60 miles east and west and 30 miles north and south. For the 1995 Wichita Assembly of Mennonites I wrote and edited a Map/Guide to the Mennonite Communities of South Central Kansas.