Sons of Meyken Wens search for her tongue screw among her ashes,

Antwerp, 1573

September 2003

vol. 58 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2003

vol. 58 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

James C. Juhnke retired from teaching history at Bethel College in 2002. He continues to be involved in various historical activities, including as an editor of Mennonite Life.

For North American Mennonites today, memories of the Anabaptist martyr tradition are a significant source of group identity. The martyrs tell us we own a faith worth dying for. They prepare us for the possibility of persecution and marginalization in our own time--especially as our pacifist convictions become unpopular in a war-crusading America. But martyr memories are not without problems.

In the holiday season of 2002, Herald Press offered its patrons, "just in time for Christmas gift giving," a leather bound gift edition of the Martyrs Mirror, "a book that is sure to please anyone interested in Anabaptist history." This edition included a "premium bonded burgundy antique leather case embossed with traditional rose design." It cost $89.99 plus tax. One can imagine Mennonite families on Christmas eve, opening this gift in the soft glow of Christmas trees and examining the etchings by the famous seventeenth century Dutch artist, Jan Luyken. The etchings graphically show Christians being tortured, drawn on the rack, beheaded and burned by fire. Over the past four decades the Martyrs Mirror has sold far more copies than any of the leading Anabaptist-Mennonite history books.

Sons of Meyken Wens search for her tongue screw among her ashes,

Antwerp, 1573

Some Mennonite holiday gift lists this past year probably included the novel Sweeter than all the World, by Rudy Wiebe, the most famous of current Mennonite writers. Wiebe's latest book, winner of the Governor General's Award in Canada, is a multi-generational Mennonite family history saga. An early chapter tells of the martyrdom of Anabaptist Meyken Wens through the eyes of her young son, Jan Adam Wens. Jan tells how the executioners prepared a tongue screw to keep his mother from testifying at the stake: "The smith pushed the curled iron onto her tongue until the flanges spread her lips as wide and hard as possible. . . . He screwed the vise down to the point of steady blood, and finally, to make certain it would never slip, with tongs he took out of his fire a white-hot iron. He laid that iron on the tip of my mother's tongue."1

During Christmas vacation, we could also read the current December issue of Mennonite Life, an online quarterly journal. There we could find a poem, "Stigmata," by Ann Hostetler, English teacher at Goshen College. The poem finds the author in a Catholic cathedral, listening to a priest's homily, and reflecting on the meaning of human suffering:

But Jan Luykens' portraits of the martyrs are images too, images that keep the sounds of our forefathers and foremothers visible, wounds we choose to pass on, saying,

"This is how others suffered for you. No matter what you do now, you can never suffer enough."

Mennonites in recent years have been remarkably persistent in choosing to pass on the wounds of the Anabaptist martyrs.2 A turning point for this interest was an immensely popular traveling museum exhibit, "The Mirror of the Martyrs," (1990) and an accompanying book by historians Robert Kreider and John Oyer. The exhibit remains on the road today, having appeared in more than sixty venues. The book has been published in five foreign languages, with Hindi, French, and Japanese editions in process. Mennonite poets and musicians in the 1990s gave renewed attention to the martyr theme. The 1997 C. Henry Smith annual peace lectureship, organized and performed by organist Shirley Sprunger King for four Mennonite colleges, was titled "Singing at the Fire: Voices of the Anabaptist Martyrs." An expanded version of the project, featuring the Eastern Mennonite University Chamber Singers, is now available on CD.3

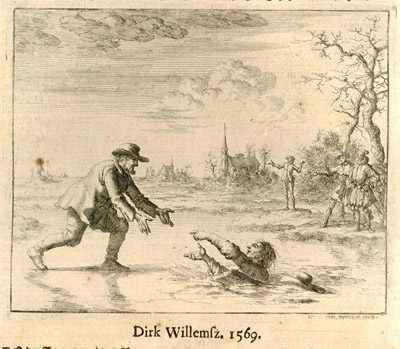

The most famous image from the Martyrs Mirror is that of Dirk Willems. It shows a condemned Anabaptist who had escaped from prison, but turned back to rescue his pursuer who had fallen through the ice. As a result of his compassion, Willems was recaptured and burned at the stake. Today that image appears on Mennonite church banners, Sunday School curriculum publications, church bulletins, conference brochures, periodical mastheads, newspapers, books, and even on the label for a (failed) Mennonite beer.4 One mission worker has said that "the Dirk Willems story is not only persistently remembered by Mennonites, but shapes our understanding of life and reality in a most profound way. . . . This story is quite possibly the most potent illustration in the Mennonite subconscious."5 The memory of Dirk Willems warns Mennonites not to expect to be rewarded for good works--a sharp contradiction to the American gospel of success.

It is appropriate for Mennonites to give account of their martyr memories in the context of an ecumenical dialogue. These memories have a great deal to do with the way we view those outside our own group--especially those who are spiritual descendants of our former persecutors. How do our martyr memories affect our view of the other?

A survey of the Mennonite martyr literature reveals that these stories as popularly told in the past decade do not tell us very much about the character and motivations of those who persecuted the Anabaptists. The original Martyrs Mirror of 1660 by Thieleman van Braght breathed an extremely hostile anti-Catholic spirit that reflected the Dutch Protestant resistance to Spanish Catholic colonial rule. The persecutors were "deceitful papists" and "bloodthirsty, ravening wolves."6 In the late twentieth century, Mennonites were inclined to more tolerant or generous characterizations of their sixteenth century persecutors. The "Mirror of the Martyrs" museum exhibit suggests that the persecutors were "good people." It asks, "Why did good people torture and kill?" and it includes a panel listing some of the thinking behind the torture and killing: "Society is one and indivisible; . . . Anabaptists destroy God's good society by disobeying the orders of our leaders; . . . Anabaptists are conspirators." But most viewers of the exhibit--with its vivid images of torture and execution--would not find convincing evidence that the killers of Anabaptists were "good people" who happened to be tragically flawed. Museum exhibit texts, of course, do not have space for analysis. In general, pathos overwhelms tragedy in popular Mennonite portrayals of Anabaptist martyrdom, including the Anabaptist film "The Radicals."

Dave and Neta Jackson, tellers of Anabaptist martyr stories, are explicit about their intention to avoid language or narrative that might embarrass spiritual descendants of the persecutors. "Right remembering," say the Jacksons, "is a testimony that even suffering and death cannot extinguish the victory that is ours in Christ Jesus." "Wrong remembering," in contrast, "focuses on the injustices done and fans the flames of hatred and revenge."7 The Jacksons' martyr stories, intended as a corrective to the biases of the Martyrs Mirror, feature simple people, faithful to the gospel, who suffer and die for their faith. Such a telling has the virtue of politeness vis-a-vis the persecutors. But it fails to engage the tragedy and irony of the martyr history. Readers are not told why the martyrs died or what was in the minds of the people who killed them. The stories lack context. The people in the stories are admirable, but they don't live in a convincingly real world. The gripping drama of martyrdom is reduced to incomprehensible pathos--people dying for reasons that don't make any sense and which their descendants are not supposed to acknowledge. Is this really right remembering?

An impulse to cover past wrongs with a code of silence lies deep within the Mennonite psyche. It is related to a peoplehood ethos of humility, yieldedness, and nonresistance. That ethos is most evident in the Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites, but it is a part of the life style and worship of more acculturated Mennonites as well. It calls upon church members to avoid speaking about another member's transgression once it has been confessed, and to generally avoid subjects that would introduce disharmony.8 Seen in its best light, Mennonite silence about the character and motives of their historical persecutors may be seen as a form of forgiveness. It is surely integral to the core values of the tradition.

On the liberal wing of the Mennonite separation-accommodation continuum are those who argue openly that the martyr memory is dysfunctional. We would do well, these people say, to stop rehearsing the stories of the martyrs and the people who killed them. Melvin Goering, a Mennonite mental hospital administrator from Kansas, has argued that Mennonites need to recover from a persecution complex which expresses itself as arrogance, superiority, and moral smugness. A martyr-based perfectionist ethic cannot be relevant to a modern world in which Mennonites find themselves responsible for authoritative administration of complex institutions. The martyr stories, said Goering, cannot "provide guidance for a people immersed in culture . . . for a people in need of a positive vision of authority and institutional ethics." Modern Mennonites need to hear not stories of rigidly righteous martyrs, but stories which assist them to "obedience with flexibility, beliefs without dogmatism, faithfulness within culture, ethical leadership within institutions, love and justice within social structures, conviction in the midst of ambiguity, dialogue without arrogance, care without condescension, openness without disintegration."9 Goering is not so much concerned that our martyr memories may offend the spiritual descendants of our former persecutors, as that they distort our own character and make us irrelevant in the modern world.

Is it possible to move beyond naive sentimentalism and simple heroism in portraying the martyr tradition? Is it possible to be more honest about the mix of admirable and repugnant elements in both our ancestors and in their persecutors? Can there be a forgiveness more rich and meaningful than the forgiveness of silence? If so, the task would seem to include a more honest and complete engagement with tragic evil in our past.

There may well be times when silence regarding past wrongs is appropriate. But failure to acknowledge and confront the evil deeds perpetrated in the past can trap us in a kind of immaturity and innocence. We need a richer knowledge of both the goodness and the sinfulness of those who persecuted our ancestors. Forgiveness, wrote Desmond Tutu, "involves trying to understand the perpetrators and so have empathy, to try to stand in their shoes and appreciate the sort of pressures and influences that might have conditioned them."10 The popular Mennonite history book by Harry Loewen and Steven Nolt, Through Fire and Water, draws its readers into a favorable portrait of Martin Luther. After Luther's insight from Romans 1:17, the text says,

From that moment on, Luther knew what Christian faith was all about. Salvation comes from a gracious God in Christ, and a person receives this grace by faith only. It is not human doing or good works that redeem and make the sinner just, but God's free grace and love in Christ. Luther was free, forgiven, and happy, and his life took on new purpose and meaning.11

Why did this good person do bad things? This text says Luther saw a connection between the Peasants Revolt and Anabaptism and became convinced "that even the peaceful Anabaptists were devils in disguise." Luther indiscriminately condemned the Anabaptists in part because he feared that people would blame him for the Peasants Revolt. This text does not go on to say how many peaceable Anabaptists were executed in Lutheran jurisdictions.

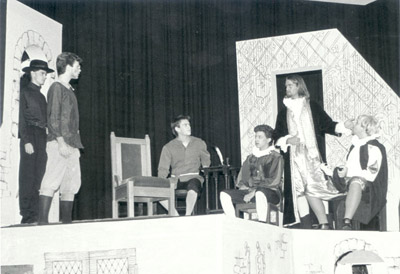

"Dirk's Exodus" performance at Bethel College 1990.

Dirk, played by Aaron Rittenhouse, standing 2nd from left.

The inquisitor, played by Rob Epp, standing at right.

My own attempt at a popular retelling of the Anabaptist martyr stories revealed to me how difficult it is to portray the martyrs and their executioners in terms that do justice to the mixture of human goodness and evil on both sides. In 1990 I wrote a full-length historical drama of the Dirk Willems story, Dirk's Exodus.12 The story included a Catholic inquisitor who has generous impulses, and who tells of his own conversion in terms that I drew from the conversion of Ignatius Loyola. I attempted to portray the inquisitor as a good man whose decisions were quite understandable, and who was trapped by tragic events and by an assigned role that led him to condemn peaceful and good Anabaptists to death. Some people who viewed the drama decided that Dirk Willems was too stubborn, and that the inquisitor was justified in his decision. One reviewer said the drama ran the risk of casting doubt on the martyr heritage and bringing "some loss of faith and pride in a tradition." On the positive side, in this reviewer's judgement, the drama might help free Mennonites "from our jail cell of intellectual pride, from our messianic delusions, and from our persecution complex."13 Most spectators, however, accepted the drama as a celebration of Dirk Willems and his heroic martyrdom. For me the experience demonstrated that Mennonites are conflicted about their martyr heritage. Nor did I think that I had succeeded in developing either Dirk Willems or the inquisitor as fully realized characters.

Right remembering of a martyr heritage is no easy task. If the stories are to be honest to what actually happened in the past, and if they are to result in forgiveness and reconciliation, we must tell accurately the extent of the persecution and suffering. And we must do all we can to understand and embrace the situation and character of those who perpetrated the persecution. The forgiveness of honest confrontation and embrace is more profound than the forgiveness of silence and forgetting.

A great hazard of martyr memories is self-righteousness. Those who would rightly remember their martyr ancestors must learn how to see them not only as victims, but flawed persons who were part of a flawed movement. This has not been easy for Mennonites, in part because, for the better part of the twentieth century, their historical agenda has been to revise the centuries-long establishment-orthodox view of Anabaptists as antinomian radicals whose true character was revealed in the violent apocalyptic kingdom at Muenster of 1534-35. The Goshen school of Anabaptist historiography, led by Harold Bender, John Horsch, and scholarly publications in The Mennonite Quarterly Review, undertook a rehabilitation of the reputation of Anabaptism.14 Bender used a theological typology to classify Reformation groups and to argue that mainstream Anabaptism, or "Anabaptism proper," was a peaceable movement which was quite different and separate from the violent Muensterites. Thus the Mennonites were not culpable for the Muenster debacle.

The Goshen school's revisionist views were very influential, but the impulse to see the Kingdom of Muenster as definitive of the Anabaptist remains very much alive. The most recent popular book on the subject, Anthony Arthur's The Tailor-King: The Rise and Fall of the Anabaptist Kingdom of Muenster, was prompted by his quest for a historical parallel to David Koresh and the Branch Davidians who were destroyed at Waco, Texas in April 1993.15 Arthur seems to be aware that most Anabaptists were peaceable people with a peaceable theology. Like most religious folk of their time, Anabaptists expected the soon return of Christ. A great majority of Anabaptists did not set an exact time and place for Christ's return, nor did most of those who did so expect to engage personally in a violent end-time fulfillment. Nevertheless, Arthur's book--and his repeated reference to the "Anabaptist Kingdom of Muenster"--conveys the impression that the Muenster episode was the definitive Anabaptist event. This may be analogous to holding the terror at Waco in 1993 as definitive of Seventh Day Adventism because David Koresh's group was an offshoot of the Adventists. It comes short of right remembering.

Historians of Anabaptism in recent years have revised the Bender school's normative Anabaptist vision. The new revisionists have shifted somewhat from theological history to social history, and have narrowed the conceptual difference between the Muensterite radicals and the wider Anabaptist movement. They have insisted on an acknowledgment of the facts of historical genesis. Muenster did arise in part out of Anabaptism. Without attempting to explore the outlines of this debate, I would suggest that right remembering requires Mennonites to acknowledge the connections between the Anabaptist movement and its violent fringe. Not the least of reasons for doing so is to confess that our attitudes towards our enemies, or those who are most unlike us, are in continual need of repair. Even as we Mennonites rightly distinguish ourselves from the violent Kingdom of Muenster, we do well to see something of ourselves in the radical fringe as we confess our own potential for anger, hatred, and revenge.

Mennonites today may find it difficult to comprehend the sixteenth century fear of anarchy which led to the killing of peaceable Anabaptists. It is somewhat easier today to understand the argument against Anabaptists that their pacifism would leave Christendom vulnerable to invasion by the infidel Turks who were at the gates of Vienna. The popular Mennonite film, The Radicals, was reasonably successful in portraying the power of this argument. It makes sense to contemporary Mennonites who are accused of not contributing to the defense of the American nation in face of threatened invasion by Communists or other evil forces.

Right remembering requires an acknowledgment that our reputedly heroic ancestors did not always do and say what we might wish they would have done and said. Perhaps Mennonites need to tell more stories of Anabaptists who recanted, or who treacherously betrayed their co-believers to the authorities. The vitriolic language that Menno Simons used against his opponents rings harsh on our ears today. In the early 1980s, in responding to the outcome of conversations between Lutherans and Mennonites in France, historian John Oyer wrote, "If descendants of sixteenth-century Lutherans feel it necessary to apologize for the condemnations issued by their spiritual ancestors, this editor does not see why late twentieth-century Mennonites should not feel it proper to apologize for at least the many nasty words sixteenth-century Anabaptists such as Melchior Rinck directed toward Lutherans." The exchange between Lutherans and Mennonites, Oyer wrote, should not be "a one-way street."16

From an Anabaptist perspective, right remembering is a part of Christian discipleship. Our ways of remembering should be conducive to our walk as disciples of Christ. Our remembering should influence our behavior. Even if we find ways to honor our ancestors while acknowledging their failings, and if we find ways to more fully engage and understand those who persecuted our ancestors, we will gain little if we do not appropriately love and forgive our neighbors, and repent of our own sins in our own time.

Part of right remembering and right living has to do with our relationships to dispossessed and disadvantaged people in our own society and overseas. The stories of the martyrs find immediate resonance among Christians in Asia, Africa, and Latin America who have vivid memories and current fears about the oppression of "Cultural Revolutions" or incidents of terror directed against believers. Robert Kreider has suggested that extensive MCC and mission involvements overseas have helped Mennonites identify with the plight of the hurting. Those people are remarkably eager to have the Anabaptist martyr stories translated into their own languages.17

Right remembering should also help us envision a future of greater wholeness and fulfillment. Martha Minow, in her book on memories of recent mass violence, warns against the wrong remembering that happens "when the truth attends to a past without affording a bridge to the future."18 If Mennonite remembering is to be both fully honest and convincingly hopeful, we will not forget the martyrs, but neither will we allow them the dominant role in our historical imagination. For our relationships with others, and for energy in kingdom work, we must nurture a balanced and positive understanding of our past as a people of God.

1. Rudy Wiebe, Sweeter Than All The World (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2001), 77.

2. The January 13, 2003, issue of Mennonite Weekly Review has two articles and an editorial by Robert Rhodes, "The age of the martyrs is far from over," 3, "New view of martyrs is online," 1-2; and "Who still reads the 'Mirror'?" 1-2.

3. See Shirley Sprunger King, Sarah Klassen, and Brent Weaver, "Singing at the Fire," Mennonite Life 52 (June 1997), 22-27. The CD, Singing at the Fire: Voices of Anabaptist Martyrs, was published in 1998 by Faith and Life Press, Newton, Kansas and Winnipeg, Manitoba.

4. David Luthy, member of the Old Order Amish and director of the Heritage Historical Library, Aylmer, Ontario, has a complete collection of the artistic and photo-reproductions of the Luyken etching of Dirk Willems. See Luthy, "Dirk Willems: His Noble Deed Lives On," Family Life, February 1995, 19-22. By January, 2003, Luthy's collection had 164 items, not including some twenty recent non-photographic renderings of the scene. Luthy to the author, January 13, 2003.

5. Dennis Byler to MennoLink, 27 May 1996 (dbyler@ctv.es).

6. Thieleman J. van Braght, The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, Fifth English Edition, trans. by Joseph F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1950), 741.

7. Dave and Neta Jackson, On Fire for Christ: Stories of Anabaptist Martyrs (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1989), 26.

8. John A. Hostetler, Amish Society, 4th ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 387-402.

9. Melvin Goering, "Dying to Be Pure: The Martyr Story," Mennonite Life 47 (December 1992), 9-15.

10. Desmond Mpilo Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness (New York: Random House, 1999), 271.

11. Harry Loewen and Steven Nolt, Through Fire and Water, An Overview of Mennonite History (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1996), 63.

12. James C. Juhnke, "Dirk's Exodus," in Four Class Acts: Kansas Theatre, ed. by Repha J. Buckman and Robert N. Lawson (Topeka, KS: Woodley Memorial Press, 1992), 85-184.

13. John Sheriff, "Dirk's Exodus, Morality Play and Modern Tragedy," Mennonite Life 47 (December 1992), 20.

14. For a historiographical review see James M. Stayer, "Was Dr. Kuehler's Conception of Early Dutch Anabaptism Historically Sound? The Historical Discussion of Anabaptist Muenster 450 Years Later," Mennonite Quarterly Review 60 (July 1986), 261-288.

15. Anthony Arthur, The Tailor-King: The Rise and Fall of the Anabaptist Kingdom of Muenster (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999), 198-9.

16. John Oyer, "Research Notes: Lutherans and Mennonites, 1980-1983," Mennonite Quarterly Review 58 (April 1984), 179.

17. Robert Kreider to the author, January 18, 2003.

18. Martha Minow, Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History after Genocide and Mass Violence (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998), 62.