Elder Gerhard Penner

September 2003

vol. 58 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2003

vol. 58 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

Mark Jantzen is a 1985 Bethel College graduate. He served two terms with Mennonite Central Committee in East Germany and Yugoslavia. After doing doctoral work in Modern European History at the University of Notre Dame, he joined Bethel's history department in 2001. He received his Ph. D. in 2002 with a dissertation titled "At Home in Germany? The Mennonites of the Vistula Delta and the Construction of a German National Identity, 1772-1880." His dissertation won the John Highbarger Memorial Prize for an exceptional Ph. D. dissertation in history at Notre Dame.

In the course of the nineteenth century, military service became so widely accepted in Germany that those who refused to serve were no longer considered proper Germans. This new understanding of citizenship was due in part to a powerful linkage between a commitment to defend the nation and a claim to be part of the nation. Universal military conscription and universal manhood suffrage were the primary expressions of defending and belonging to the nation, a linkage that remains a crucial aspect of modern nationalism.1 At the same time, however, it made the continued existence of traditional Mennonite communities in Germany impossible, forcing Mennonites to change their religion or emigrate.

The roughly twelve thousand Mennonites near Danzig/Gdansk in the Vistula Delta comprised both the largest and the most conservative settlement of the twenty thousand Mennonites in Germany. The Vistula Delta community was organized into roughly twenty congregations, each led by an elder and preachers who had been elected for life. Until the end of the nineteenth century Mennonites constituted Germany's largest Free-Church minority.2

The linkage between belonging to the nation and serving in its army found its first widespread application in Germany in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian war of 1866.3 The resulting shift in domestic politics created a Germany in which for the first time it became illegal for Mennonites to avoid military service. This pressure split the Mennonite community of the Vistula Delta into pro and anti-military service camps, making this story an important early case study of the adaptation of a pacifist religious minority to the stresses of modern nationalism. Most Mennonites chose to stay in Germany and to adapt their religious commitments to the new requirements. The minority of Mennonites who decided to maintain their religious traditions found themselves compelled to emigrate before they had time to consider all the ramifications of selecting a final destination. They quickly discovered problems with the traditional solution of resettlement in Russia. Forced to seek alternatives, they found new opportunities in Gage and Jefferson counties in Nebraska and in Harvey, Butler, and Marion counties in Kansas.

Following the Partitions of Poland in the late eighteenth century, the Prussian government exempted the Mennonites of the Vistula Delta from military service in return for a collective annual fee. This exemption came with an additional price. Starting with a royal Edict of 1789, a number of laws restricted Mennonites' legal rights. They needed special permission from Berlin in order to buy property from non-Mennonites, which was rarely granted. Males from outside were not allowed to join the Mennonite church, since those who were not born with the military exemption were not allowed to gain it by converting. These hardships resulted in significant emigration of Mennonites from the Vistula Delta to southern Russia throughout the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century.4

In the aftermath of the 1848 revolution in Prussia, King Frederick William IV confirmed the Mennonites' exemption over the objections of the newly constituted Parliament (Landtag). Discussion of Mennonite policy in the areas of church taxes, military service, or land purchases came up in the Prussian Parliament in several sessions of the 1850s. Parliamentary impatience over an often-promised but never-delivered governmental initiative on Mennonites led to a law being introduced from the floor in 1861 that would have granted Mennonites most civil rights in exchange for requiring them to serve in the military, placing the debate over the Mennonites' exemption squarely alongside the most contentious issue of Prussian politics.5

The early 1860s marked Prussia's deepest political crisis since 1848. The crown and the parliament deadlocked over the limits of royal power, a conflict centered on the question of who ultimately controlled the army. That debate was colored by a long-standing tension between liberals who looked to a militia based on universal military service as a bulwark against absolutist royal power and the crown and conservatives who favored a standing army with longer terms of service that could reliably be turned against internal enemies.6 Parliamentary and societal debates about military service in this decade were therefore always arguments about the future identity of Germany as well.

The Prussian victory in 1866 over Austria stunned Europeans and ended Prussia's political stalemate in favor of the monarchy. Even more shocking were Bismarck's revolutionary policies of annexing the northern German kingdoms that had fought against Prussia and introducing universal manhood suffrage. These events triggered important changes in German domestic politics. Many liberals abandoned the principle of parliamentary oversight over the army in light of its success in achieving German unification. In the hopes of sharing in political power, some liberals split off to form a new party in 1867, the National Liberal Party, which supported Bismarck's policies.7

The same year Bismarck created a North German Confederation, which consisted of a much enlarged Prussia and its north and central German allies. Bismarck himself drafted the constitution for this new state, which included both the provision that all North Germans were liable for conscription and universal suffrage for males.8 Prussia's victory and subsequent hegemony in Germany cast the Prussian military as the role model for the army of the North German Confederation that emerged in 1867 and for the Imperial army after 1871. Prussia's style of universal conscription was therefore extended throughout Germany.

In October 1867 the new Confederation Parliament debated the government's proposed military service law. Among other provisions, the government proposed to reinstate military exemptions for three classes of North Germans: the ruling Hohenzollern family of Prussia, the ruling families of formerly sovereign German states, and Mennonites.9

Representatives from both the left and the right in the Parliament vehemently attacked the suggestion that some Germans should be exempted from military service. The left liberal Franz Duncker argued that conscription's political importance was connected to its universality, for only an army based on universal conscription emphasized the people's sovereignty over the king's. Conscription, he claimed, was "only a great and holy principle if it really allows no exceptions at all."10 The constitution, he continued, must be a law for all and both Mennonite and noble exemptions therefore must not be allowed.

On the right, National Liberals emphasized the threat to the principles of nationalism that such an arrangement entailed. Adolf Weber made the argument most succinctly when he exclaimed, "Whoever will not defend his homeland (Heimath) should leave it! Whoever will not defend his fatherland does not have one!"11 Julius von Hennig, a member of the National Liberal leadership, detailed for the Parliament in great length what he saw as the shameful history of Mennonite exemption. He lamented the status quo in the Vistula Delta, which allowed Mennonites to get out of military service at the price of only one half Reichsthaler per person per year.12 Both Henning and Weber, however, supported the nobles' exemption from military service. They considered it to be based on state treaties, which could only be revised with the consent of those involved.13

The proposal of the government to maintain the Mennonites' exemption was easily voted down. The nobles' military exemption in contrast passed by a large majority.14 In upholding the noble exemption while voting down the Mennonite exemption, the National Liberals could both signal their support for the government's military proposals and move the liberal project of equal laws for all forward on a smaller - and politically safer - front. Likewise left liberals could at least salvage one small victory by extending universal conscription to an additional group. The North German Parliament had full knowledge of Mennonites' religious scruples and explicitly ruled out exceptions for them when it codified the link between membership in the German nation and service in the German military.

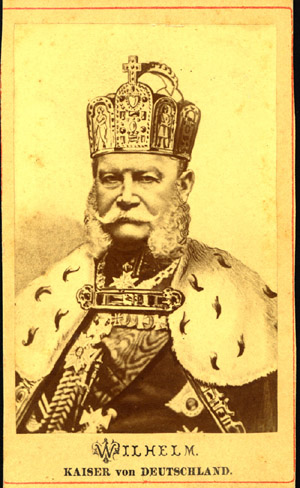

Much of the Mennonite leadership did not see the situation as hopeless. They expected that the king would be willing and able to intervene on their behalf as he had in the past. The first step, taken on October 23, 1867, was to dispatch a deputation of five Elders to Berlin.15 The key leader was Elder Gerhard Penner of Heubuden, the largest Mennonite congregation in the Vistula Delta. He subsequently became the main champion of Mennonite emigration to the United States. Upon arrival the delegation spent time observing the Confederation Parliament.16 They were unable, however, to affect the outcome of the debate.

Elder Gerhard Penner

Mennonite church at Heubuden, West Prussia

Mennonite church at Ladekopp, West Prussia, 1930

Mennonite church at Fürstenwerder, West Prussia

To the Mennonites' dismay, the king signed the military service law on November 9, 1867. In response, the collective Mennonite leadership of the Vistula Delta sent numerous petitions to Berlin. The petitioners acknowledged the tension between the demands of citizenship and their religious scruples, but gave religious convictions the higher priority, claiming "We are willing to lay down our lives for our brothers, but we can not kill them. Our Lord and Savior commanded 'Love your enemies,' and we wish to obey."17

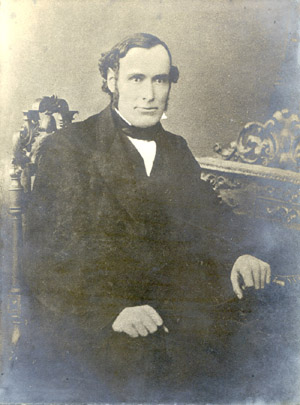

Mennonites also followed up with another deputation of the same five elders, who on February 25, 1868, met with King William I. They requested either continued exemption or at a minimum an extension to provide them time to emigrate. Clearly some Mennonites were already making plans to leave Prussia. The king assured them that provisions were in the works to take their religious scruples into account.18

King/Kaiser William I

The provision the king had in mind was a suggestion forwarded by Bismarck that Mennonites be allowed to serve in non-combatant roles. On March 3, 1868, a cabinet order to this effect was signed.19 Mennonites who did not volunteer for active duty were to be drafted into non-combatant positions and would serve as clerks, medics, artisans, or wagoners. Soon afterward the Prussian parliament voted to abolish the special tax the Mennonites had paid for their group exemption. A directive by the Minister of the Interior lifted all restrictions on buying property. Mennonites, however, still paid special church taxes to the Protestant state church and their congregations were not recognized as legal entities.

The new legal possibility of non-combatant service meant that Mennonites no longer only had to choose between regular military service or emigration. Instead they were forced to consider again where the limits of conscience lay. The different answers to that question split the Vistula River Mennonite community into bitterly squabbling factions. The fact that the leadership was more conservative than the laity led some lay members to initiate a petition drive in the fall of 1868.

This lay-led petition sought the revocation of the 1789 Mennonite Edict and the right to incorporate their congregations, a status otherwise reserved for Protestants and Catholics. The effort eventually garnered almost 1,300 signatures.20 Especially striking in this context of demanding full civil rights was the absence of female signatures on the petition. Earlier Mennonite petitions to local officials that had dealt with local village affairs typically had been signed by all property owners, including widows.21 Women's signatures, however, were completely missing from this petition bound for Berlin from potential Prussian soldiers. Perhaps the leaders of the petition drive were uneasy about having women sign a document that called for greater civil rights based on military service. The lack of widows' signatures certainly highlights the masculine basis for Mennonite civil rights. Property rights no longer factored into the debate, since Mennonites no longer faced those restrictions. The petition signers argued for civil rights on the basis of what was due all male Germans who agreed to defend the state.

Mennonite demands for civil rights were finally taken into account in 1874 with the passage of the Law Concerning the Circumstances of the Mennonites. That law recognized their congregations as legal entities that could own property. The law fudged on the issue of church taxes, however, and some Mennonites continued to pay taxes to the Protestant church until the 1920s.22 Nonetheless, the 1874 Mennonite law marked the formal emancipation of the Mennonites, five years after Jewish emancipation in the North German Confederation.23

At the same time as some lay leaders were petitioning for their civil rights, the leadership of the conservatives mounted a petition drive with exactly the opposite intention. In March 1869 their effort collected over 1,800 signatures, five hundred more than the lay-led petition.24 The main demand of these petitioners was reinstatement of the Mennonite exemption. The traditionalists' petition did acknowledge a tension between citizens' rights and duties. The conservative leadership, however, felt the liberals in Parliament were most responsible for their plight and had singled out Mennonites for punishment because they tended to vote conservative. If Mennonite voting patterns were the problem, the petitioners proposed a simple solution: "Why allow us to vote? We do not demand it and would be more than happy to give it up at any time."25

Thus in early 1869 over eighteen hundred Mennonites petitioned for reinstatement of their exemption at the cost of civil rights, while at the end of the year almost thirteen hundred men signed a petition demanding the exact opposite. Yet the conservatives' petition had no effect on public policy. There was to be no place in the new Germany for male citizens who would not serve in the military. Having failed to influence the Parliament or the government, Mennonites sought relief from the Prussian court system.

The plans of even a few Mennonite families to emigrate immediately over the issue of military service forced the government to consider the issue of allowing draft-age males to emigrate. For example, in September 1868 Abraham Bergman of Bröske wanted to emigrate with three sons of or approaching draft age; Abraham, age twenty; Peter age eighteen; and Jacob, age sixteen.26 As a result of this and other cases, the State Ministry on November 28 ordered the army to grant Mennonites in the Vistula Delta a two-year reprieve from military service if they so desired. In addition, exit visas that included dismissal from Prussian citizenship were to be given to these Mennonites.27

Gerhard Penner and his allies in leadership put great pressure on their congregations to emigrate, applying church discipline to members who opted for military service in any form. This practice sparked conflict in several congregations. For example, the Elbing-Ellerwald congregation experienced a sharp conflict in late 1869 between its elder, Johann Andreas, and his flock. This congregation maintained two meeting houses, one in the city of Elbing and the other in the rural area of Ellerwald to the west of town. Especially the urban members insisted on accepting non-combatant military service since they did not want to emigrate and claimed that "no suitable emigration option" was available.28 Elder Andreas considered those unwilling to emigrate not to be Mennonites anymore and refused to serve communion to or baptize members of families holding such views. The Elbing members in return barred him from the city pulpit.

Elder Johann Andreas and his wife Anna (Fast), ca. 1870

The Ellerwald group could not reach a consensus to depose Andreas as Elbing members insisted. A stalemate ensued. Since Andreas' sons were past draft age, he could afford to wait out the government. Ellerwald members who had sons being registered for the draft, however, could not wait. In the spring of 1870 they took the unprecedented step of electing a co-elder to serve alongside Andreas, in effect de facto deposing Andreas without having to take the painful step of actually throwing him out of office. When Andreas left for the United States in 1876, he took the church membership book with him as a symbol of his authority over the remnant of what he considered the true Mennonite church.29

After several additional petitions to the government brought no response, more families, especially those with draft-age sons, turned to emigration as the only viable option to avoid military service.30 Legal emigration required the permission of the military bureaucracy. Officials were readily issuing the exit passes needed, revoking the Mennonites' Prussian citizenship at the same time. Since pass bearers had become non-Prussians they were of course exempt from military service.31 The Mennonite regulations issued in November of 1868 made these passes easy to obtain, and in 1869 interest in them increased. Allowing emigration in this fashion in fact contradicted state policy. In 1863 Bismarck had ordered his Minister of Commerce to discourage it since "to emigrate was to betray the fatherland."32 Mennonites, however, had little trouble getting exit passes, a sign they were not wanted in Germany if they would not serve in the army.

The government granted such exit passes to allow emigrants time to settle their affairs before departing. According to the Danzig District Government, some Mennonites, having secured these passes for their sons, were taking far too long to depart. Local officials argued that Mennonites were avoiding military service by renouncing their citizenship yet staying in the country.33 One of them, David van Riesen, was drafted as a medic in 1871 despite holding a valid exit permit. Penner and the Heubuden church board protested on his behalf. An investigation revealed that since the exit pass revoked van Riesen's citizenship, he could not be drafted. Count Friedrich zu Eulenburg, Prussian Minister of the Interior, ordered Danzig officials to drop the case because a new law had recently closed this loophole by putting a six-month expiration date on new exit passes.34 The news of van Riesen's official release from military service created a minor stir in Mennonite circles. Some Mennonites in other congregations gained the impression that Penner was able to protect individuals from military service and sought to join the Heubuden congregation on this account.35

Once the exit pass loophole was closed, individual cases became more acute, pushing conservative royalist Mennonites to break the law. By 1873 the Danzig District Government reported to Berlin a need to use "energetic coercion (energische Zwangsmaßregeln)" to get recalcitrant Mennonites to bring their sons in for mustering.36

Johann Dyck's case followed immediately on the heels of David van Riesen's and provided an example of the "energetic coercion" that the District Government was now using. Dyck was still in Prussia when his exit pass expired under the new six-month deadline.37 Attempts to secure an extension yielded only a draft notice to serve as a wagoner.38 As the April 22, 1872, induction date approached, Dyck went into hiding, but the police found him. He was delivered to the military office in Marienburg. Since he refused to accept the train ticket to Berlin, where he was to be stationed, he was kept overnight under military arrest. The next morning a military detachment escorted him to Berlin on the train. Once there he refused to put on his uniform. It was put on him by force. He refused to swear the oath of induction and loyalty to the emperor. For these offenses he received multiple sentences of several days in confinement. After they had been served, he was asked once more to swear the oath. He refused and was confined again. This cycle repeated itself numerous times with the length of confinement after each refusal reaching seven days. In September the military admitted that no progress had been made in breaking Dyck's will.39 Penner and Elder Wilhelm Ewert of the tiny Obernessau congregation up the Vistula River near Thorn traveled in November to Berlin on Dyck's behalf. They petitioned the emperor at least to let Dyck emigrate if he could not be exempted. All their efforts were to no avail.40

Elder Wilhelm Ewert, ca. 1880

The Dyck case made the futility of depending on the emperor excruciatingly clear to Penner and his dwindling base of support. In their June 1872 petition to the Ministers of War, the Interior, Justice, and Culture, the Penner group admitted their faith "in the emperor was sorely tested by the coercion the military employs against our brother to force him to swear an oath and to deny his faith."41 The government notified the traditionalists in September 1873 that exit passes would no longer be granted.42 Mennonites who did not emigrate before their sons turned twenty could expect those boys to receive the same treatment that Johann Dyck had experienced.

To the very end Penner continued to appeal to the Prussian tradition of religious freedom. In the 1870s this rhetorical device had lost all its appeal. The Prussian state was engaged in a struggle, the Kulturkampf, to deprive the Catholic church of political power.43 The Prussian government cooperated with a wide spectrum of anti-clerical liberals to pursue its new policy. Their horror at the idea that Catholicism might be more important to German Catholics than national unity found its parallel in liberals' rejection of any special pleading by Mennonites.44

Gerhard Penner experienced the government's willingness to apply one of these anti-Catholic laws to Mennonites. A May 13, 1874, law on church discipline forbade the excommunication of members for obeying state laws. By 1874 Penner had banned at least three young men from his congregation because they had agreed to serve in the military. He attempted to block one of the three, Johann Reimer of Gross Lichtenau, from getting married in the Heubuden church. Reimer's complaints to the government resulted in energetic calls from Berlin to the Danzig District Government to investigate this case.45

On June 7, 1874, Bernhard Fieguth, a young man from the Heubuden congregation, appeared at church. It was communion Sunday, which Mennonite congregations celebrated only once or twice a year. Fieguth had joined the army in 1873 and been excommunicated for this transgression. Fieguth's father boasted to other members during the previous week that Penner would have to give his son communion, pay a fine, or go to jail. Elder Penner's son Heinrich stopped Fieguth as he entered the church and asked if he really would seek to partake in communion. Fieguth replied he wished to determine if Elder Penner would give him communion or not. Penner refused him. A week later the county prosecutor filed charges against Penner for violating the May 13, 1873 law concerning the limits of church discipline.46

The Marienburg county court on September 1, 1874, sentenced Penner to pay a fine of 25 Reichsthaler or serve a week in jail.47 Penner appealed the case all the way to Berlin. In upholding Penner's conviction in June 1875 the High Court in Berlin concluded that as long as Mennonites lived in Germany they would have to obey the May 13 law. The court's ruling delineated the official view of the proper relationship between Mennonites and the state. Penner had accused the state of legislating changes to the Mennonites' confession of faith by requiring military service. The High Court disagreed: "The state does not demand that religious communities adjust their confessions according to the law, the state demands only that all citizens regardless of confession obey the laws."48

Once all legal and political avenues to avoid military service had been exhausted, emigration remained the only escape from the Prussian army. Opposition to the draft had created a small, but highly committed Mennonite community in the Vistula Delta that refused even to take communion with those Mennonites who accepted military service. Even though they wanted to settle together, differences over what constituted the best location on the Great Plains broke up traditionalist Mennonites' solidarity where German government pressure had failed. No solid figures exist on the extent of Mennonite migration out of the Vistula River basin in the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s. Government figures cited twelve thousand Mennonites in the province of Prussia in 1864 and only ten thousand in 1874, suggesting migration of two thousand or 16 percent.49 The record of arrival in America, however, suggests that fewer than half this number crossed the Atlantic.50 Others clearly moved to Russia throughout the 1860s, but how many is not known.51

After 1867 the stream of emigration to the Mennonite colonies in Russia picked up. For example, in 1869 alone 2 percent of the Mennonite population of the Danzig district emigrated to Russia.52 In 1870 Elder Wilhelm Ewert of Obernessau together with one other person went to Russia to investigate possibilities of further settlement.53 Other sources, however, warned the Mennonites that Russia would also institute conscription. For example, the Mennonite delegation to Berlin in 1868 requested Crown Prince Frederick's intervention on their behalf so that they would not have to emigrate. Frederick asked where they planned to go. When he heard that they intended to go to southern Russia, he replied "Then keep the door open for your children to return to Prussia, for Russia will soon have what we have here and then you will regret your decision."54 By 1870 the plans of the Russian government to institute the draft were well known, and emigration plans shifted to the United States.55

Emigration to the United States was a riskier undertaking than going to Russia. Prussian Mennonites had a well-established family and church network to ease the way to the east. Some Mennonites, however, considered the United States a refuge for criminals.56 Nonetheless, already in February 1870 Elder Abraham Esau of Tiegenhagen started collecting money to send a deputation to investigate America.57 German territory east of the Elbe was the main source of German emigrants to America after 1880, so the Vistula Delta Mennonites were not alone in their endeavor.58 Mennonites did have a few family ties to the new world, including Gerhard Wiebe in Ohio, a half-brother of the emigration proponent and Elder, Johann Wiebe.59 Elder Penner was also interested in the possibility of emigrating to America. He wrote to the American Embassy seeking information in April 1872, the month that Johann Dyck was drafted. Alexander Blass's reply on behalf of the embassy in December was promising, if somewhat vague on assurances of freedom from military service.60

As it appeared likely that the Mennonite exemption in Russia would also be revoked, Russian Mennonites likewise started looking toward America. Cornelius Jansen, who had lived for a while as a boy in Elder Gerhard Penner's home, became a leader of the emigration drive in Russia. He had moved in 1850 from Schidlitz/Siedlce, a suburb of Danzig, to Berdyansk, Russia, a port on the Black Sea. There he learned English from Quaker neighbors. In 1871 he contacted the American consulate in Odessa about immigration possibilities. He kept Penner and others in Prussia informed of his findings, adding important encouragement to the push to emigrate.61 When some Russian Mennonites in 1873 organized a deputation to America, Elder Wilhelm Ewert joined them.62

Cornelius Jansen, 1873

One-third of Russia's Mennonites, roughly 17,000 people, ended up emigrating to the United States and Canada in the 1870s. Their representatives spoke with President Grant and other national politicians seeking military exemption, but in the end were satisfied with rather uncertain promises. Mennonites who remained in Russia accepted the alternative finally allowed by the Russian government, which placed Mennonite young men in a civilian forestry service. Thus the several hundred Prussian Mennonites who ended up emigrating were less than 10% of the 10,000 Mennonites who arrived in the US in the 1870s.63

Following favorable reports from the deputation, Mennonite emigration from Prussia to the United States began in 1874.64 Cornelius Jansen had been expelled from Russia the year before for promoting emigration. During the family's stopover in the Vistula Delta on their way to America, his son Peter fell in love with seventeen-year old Gertrude Penner, a niece of Elder Penner. The Jansen family eventually settled in Nebraska, founding the town of Jansen with other Mennonites from Russia. In the interval, Gertrude became an emigration advocate in the Vistula Delta, threatening to cross the Atlantic alone if the others were not yet ready to go.65

Peter Jansen (left, standing) and Gertrude Penner Jansen (left, sitting),

with other family members, ca. 1900

Elder Wilhelm Ewert started the move of Prussian Mennonites to Kansas. In April 1874 his family, plus two another families and a single woman, Anna Janz, left the Vistula River valley.66 They were joined by Mennonites families from Russian Poland and settled in Marion County. Ewert had selected this area himself on his 1873 trip to North America and was joined by other Mennonites from Russia to whom he had recommended it. He became the founding Elder of a new congregation, Bruderthal Mennonite Church, which was mostly comprised of Russian Mennonites.67

On June 15, 1876 Elder Johann Andreas of Elbing-Ellerwald led a group of over one hundred people through pouring rain to the train station in Simonsdorf, the closest station to the village of Heubuden. Gertrude Penner was among them. The train took them to Bremen, where they embarked for New York City.68 Several families from the urban Danzig congregation, led by Deacon Ludwig Eduard Zimmermann left as well.69 They arrived in New York on July 1, 1876. Seven families left for Halstead, Kansas, where friends were expecting them. The larger group spent two days on the train and arrived in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, on the evening of the third. Their first day of leisure to explore their new homeland was thus America's centennial.70 In Mount Pleasant they were the guests of Cornelius Jansen, who had taken up temporary residence there while his son Peter worked to establish their new home in Nebraska.71

Deacon Ludwig Eduard Zimmermann

The Heubuden group had been determined to settle together in the new country. Some families, however, had personal ties to various groups of Russian Mennonites who had already settled in different areas of the Great Plains. Opinions of the relative value of Kansas and Nebraska diverged as well. Cornelius Jansen, for example, had purchased 20,000 acres in Jefferson County, Nebraska, on behalf of Russian Mennonite immigrants. He thought the climate was ideal for raising sheep and making money from wool. The free wells provided by the Burlington and Missouri Railroad, which had sold Jansen the land, had clinched this deal.72 Others, however, thought the available land in Nebraska was too hilly and that the climate there might only be suited to spring wheat.73

One part of the group ended up founding two sister congregations in Butler County, Kansas. Six of the seven families who originally went to stay with friends in Kansas ended up purchasing property in the Whitewater area and were soon joined by some families from Mount Pleasant. In 1878 they founded the Emmaus Mennonite Church, which was led by Elder Leonhard Sudermann. Sudermann had been the elder of Cornelius Jansen's congregation in Russia and worked closely with Jansen to promote emigration among Russian Mennonites. Like Jansen, he had been born and raised in Prussia, in his case in the Heubuden congregation itself.74 Subsequent arrivals from Prussia purchased land further away from the church, resulting in Zion Mennonite Church being chartered in 1887. That same year the Chicago, Kansas, and Nebraska Railroad built a line through the area of Mennonite settlement. After consulting with the Mennonite settlers, the railroad named the new town they founded Elbing in honor of the Vistula Delta origins of this immigrant group.75

Emmaus Mennonite Church, near Elbing, Kansas. In front are Leonhard

Sudermann, his wife Marie (Sudermann) Sudermann, and an unidentified child,

ca. 1880

Elder Leonhard Sudermann, ca. 1870

The larger part of the Mount Pleasant group settled in Nebraska on land in Gage County close to Jansen's Jefferson county settlement.76 Their arrival in Beatrice merited attention in the local press. The Beatrice Express praised the wealth of the new Prussian immigrants, estimating their collective worth at various times from $50,000 to $500,000.77 Elder Penner joined the group in 1877, having waited out the results of his trial in Prussia. He brought the Heubuden communion set with him as a symbol of his authority and of his conviction that only Mennonites who refused to join the army had remained true to their faith.78 His followers in Prussia had formed their own congregation to avoid further troubles over the issue of communion. The group was known colloquially as the "immigrants congregation." Penner's son Heinrich led this group until 1884 when he himself left for Beatrice. Immigration from Prussia to the Great Plains continued in a trickle until at least 1892.79

Original building of First Mennonite Church, Beatrice, Nebraska

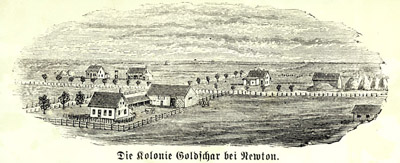

In 1876 a third group of three families from the Heubuden area, apparently traveling independently, arrived in the area of Newton, Kansas. In 1878 other families from Heubuden joined them. One of the newcomers was a preacher, Peter Claassen, who organized First Mennonite Church in Newton. The congregation grew steadily from immigration over the next decade, reaching 126 members by 1889.80

Goldschar village near Newton, Kansas (a village name transferred from Prussia)

Preacher Peter Claassen and his wife Anna (Andres), ca. 1880

Thus Mennonites who tenaciously clung together in their opposition to the draft in Prussia and Germany in the 1860s and 1870s found themselves scattered between five counties and five congregations on the Great Plains in the 1880s. The vision of maintaining congregations that rejected any participation in war also developed unevenly in the New World. A few members from these churches served in World War I and many more did so in World War II.81 Despite the partial failure of the original vision, remnants of a dramatic confrontation with German militarism in the 1860s can still be seen in some of the Mennonite settlements of the Great Plains.

1. Of the massive literature on nationalism I have found the following particularly helpful: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 1991); E. J. Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780. Programme, Myth, Reality, 2d ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992); and Dieter Langewiesche, Nation, Nationalismus und Nationalstaat in Deutschland und Europa (Munich: C. H. Beck Verlag, 2000).

2. Two overviews of Mennonites in the Vistula Delta are Wilhelm Mannhardt, Die Wehrfreiheit der Altpreußischen Mennoniten (Marienburg: Selbstverlag der altpreußischen Mennonitengemeinden, 1863) and Horst Penner, Die Ost- und Westpreußischen Mennoniten, 2 vols. (Weierhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1978 and Kirchheimbolanden: Selbstverlag, 1987). Free-Church minority here means neither Catholic, Lutheran, nor Reformed and not derived from one of these groups. Gerhard Besier, Religion-Nation-Kultur: Die Geschichte der christlichen Kirchen in den gesellschaftlichen Umbrüchen des 19. Jahrhunderts (Neukirchener: Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1992), 77.

3. The centrality of 1866 is indicated in the structure of several influential surveys that break the history of nineteenth-century Germany at this date. See for example Thomas Nipperdey, Germany from Napoleon to Bismarck, 1800-1866 (Dublin: Gill Macmillan Ltd, 1996) and the Oxford History of Modern Europe series: Sheehan, German History, 1770-1866 (Oxford: Claredon Press, 1989) and Gordon Craig, German History, 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, 1978). Hagen Schulze ends with 1867, The Course of German Nationalism: From Frederick the Great to Bismarck, 1763-1867 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

4. Mannhardt, Wehrfreiheit, 120-202.

5. Mannhardt, Wehrfreiheit, 201.

6. For a detailed survey of the constitutional struggle of the 1860s, see Ernst Rudolf Huber, Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789, 4 vols. (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1957-69), 3:275-377 and Gerhard Ritter, The Sword and the Scepter: the Problem of Militarism in Germany, 4 vols. (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1969-1973), 1:123-158.

7. James Sheehan, German Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 123-140.

8. Huber, Verfassungsgeschichte, 3:649-50. Otto Pflanze, Bismarck and the Development of Germany, 2d ed., 3 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 1:341-61. Craig, Germany, 43-6. Bismarck severely limited the authority given the North German Confederation's Parliament and thus blunted the power of manhood suffrage even as he as made political hay out of the principal of one man, one vote.

9. The final version of the law is reprinted in Eugen von Frauenholz, ed., Entwicklungsgeschichte des Deutschen Heerwesens, 5 vols. (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1935-41), 5:575-80. Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (GStA), Berlin, Hauptabteilung (HA) I, Repositur 77 (Innenministerium), Titel 31 (Mennonitensachen), no. 2, vol. 9, fols. 133-159 contains the Stenographische Berichte for the debates in the Confederation House of Representatives over this law on October 17 and 18, 1867. In the following these protocols will be cited as StB, Bund HdA and by the printed page numbers.

10. StB, Bund HdA, 465.

11. StB, Bund HdA, 469.

12. StB, Bund HdA, 466-8. Max Schwarz, MdR. Biographisches Handbuch der Reichstage (Hanover: Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen, 1965), 344. Bernhard Mann, ed., Biographisches Handbuch für das Preussische Abgeordnetenhaus 1867-1918 (Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag, 1988), 174.

13. StB, Bund HdA, 466, 469. The exemption of the mediatized nobles was first guaranteed by article 14 of the Deutsche Bundesakte of 1815 which regulated the status of former sovereigns, reprinted in Ernst Rudolf Huber, ed., Dokumente zur Deutschen Verfassungsgeschichte, 3 vols. (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1961-6), 1:75-81.

14. StB, Bund HdA, 473-4.

15. The five elders were Gerhard Penner, Heubuden; Johann Toews, Ladekopp; Johann Wiebe, Fürstenwerder; Peter Bartel, Gruppe; and Johann Penner, Thiensdorf. Penner, Toews, and Wiebe were Neopietist conservatives who later emigrated rather than accept military service. Bartel later took the middle road on the issue of military service, accepting noncombatant status but making it a requirement for continued membership in his church. Johann Penner was the "liberal" of the group, later allowing members in his congregation to serve as either noncombatants or regular soldiers. Hermann Gottlieb Mannhardt, "Zur Entstehung und Geschichte der Königliche Kabinettsordre vom 3. März 1868, betreffend den Heeresdienst der Mennoniten," in Christlicher Gemeinde-Kalender 28 (1919), 103-5, discusses these three groupings among Mennonites at the time.

16. Peter Bartel, "Beschreibung der persönliche Bemühung der fünf Aeltesten bei den Hohen und Allerhöchsten Staatsmännern in Berlin um Wiederheraushelfung aus dem Reichsgesetz, worin der Reichstag uns Mennoniten am 9. November 1867 versetzt hat," Christlicher Gemeinde-Kalender 29 (1920): 70-1. This handwritten document was preserved in the congregational records of Bartel's congregation and published for the first time in 1918 in L. Stobbe, Montau-Gruppe. Ein Gedenkblatt an die Besiedelung der Schwetz-Neuenburger Niederung durch höllandische Mennoniten im Jahre 1568 (Verlag der beiden Mennoniten-Gemeinden Montau-Gruppe, 1918), 63-73. The original document was dated 1868 and appears to have been written immediately upon Bartel's return.

17. GStA, HA I, Repositur 76 (Kulturministerium), III (Evangelisch-Geistliche Angelegenheiten), Sektion 1 (Generalia), Abteilung XIIIa (Sekten- und Judensachen), no. 2 (Die Angelegenheiten der Mennoniten), vol. 8, fols. 237-9. A similar petition to the king is in ibid., fols. 240-3.

18. Bartel, "Beschreibung," 75-6. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 31, no. 2, vol. 9, fol. 191, confirms the Elders' appointment at 1:45 pm with the king.

19. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t (Militärpflicht), no. 5 (Acta betr. die Militarpflichtigkeit der Mennoniten), vol. 1, n.p., 20 Nov. 1867. Penner, Mennoniten, 2:70-9.

20. Copies of this petition and the signatures are in GStA, HA I, Rep. 76, III, Sekt. 1, Abt. XIIIa, no. 2, vol. 9, fols. 187-225, and fols. 39-100.

21. As one of many examples of female participation in local petitions, see GStA, HA I, Rep. 76, III, Sekt. 1, Abt. XIIIa, no. 2, vol. 7, fols. 272-3, where the widows Matthies and Esau were two of the five petitioners from Wernersdorf who in 1860 complained about having to pay rite of passage fees to the local Protestant pastor.

22. Penner, Mennoniten, 2:113-7.

23. Annegret H. Brammer, Judenpolitik und Judengesetzgebung in Preußen 1812 bis 1847 mit einem Ausblick auf das Gleichberechtigungsgesetz des Norddeutschen Bundes von 1869 (Berlin: Schelzky und Jeep, 1987).

24. A printed version of the petition is available in GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 1, n.p., 4 March, 1869. I was unable to find the signatures. The report of the House of Representatives' Petition Commission noted 1,831 signatures, GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 31, no.2, vol. 9, fol. 272v.

25. "Aber warum läßt man uns das Wahlrecht? Wir verlangen es nicht und sind gern bereit, es jeden Augenblick aufzugeben," GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 1, n.p., 4 March, 1869, 4-5.

26. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 1, n.p., 3 Sept. 1868 and 10 Sept. 1868. Abraham Senior made it clear to the officials that he was going to Russia in order to keep his sons out of the Prussian army.

27. The Ministerial Decree is reprinted in English translation in Robert Barclay, The Inner Life of the Religious Societies of the Commonwealth (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1876), 616-7. The accompanying instructions to the army bureaucracy are in GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 31, no. 2, vol. 9, fol. 223. On the same day, Bismarck wrote to Elder Penner informing him of the State Ministry's decision, GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 1, n.p., 28 Nov. 1868.

28. Mennonitische Forschungsstelle, Weierhof, Germany, Elbing-Ellerwald Kirchenbuch 1870, 3-4.

29. Ibid., 4-11.

30. For a sample of the numerous petitions Penner and his associates sent to Berlin, see GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit.31, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., 19 Nov, 1869 and 7 Febr., 1870, and Rep. 89 (Geheimer Zivilkabinett), no. 23719, n.p., 14 April 1871.

31. Most emigration of draft-aged men was taking place illegally. For example, the county of Graudenz in 1868 issued only six official permits while 120 draft-aged males emigrated. In 1871 no permits were issued and 175 draft-aged males left, Archiwum Pastwowe w Gdansku, Gdansk, Poland, Sygnatur 10, no. 1552 (Tabelle der in Preussen vorgekommenen Ein- und Auswanderung), vol. 2 (1866-1873), fols. 246, 498. This county was home to Peter Bartel's Montau-Gruppe congregation, but none of the emigrants listed were Mennonite.

32. Mack Walker, Germany and the Emigration, 1816-1885 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 178. On emigration and military service in the 1860s in Prussia, see ibid., 179-80.

33. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., 31 May 1870, Danzig District Government to the Königsberg Provincial Government, which forwarded the report to Minister of the Interior Eulenburg in Berlin.

34. Related documents are in ibid., n.p., 11 May, 15 and 27 June, 11 Sept., 21 Oct., and 7 Nov. 1871.

35. Jacob Mannhardt, "Traurede," Mennonitische Blätter 19, no. 4 (May 1872): 30.

36. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., 23 June 1873, Danzig District Government to Eulenburg.

37. Ibid., n.p., Koczelitzki, 28 Dec. 1871, Petition of Elders Penner, D. and W. Ewert, Andreas and Wiebe, ten preachers, and three deacons to the emperor.

38. A copy of the draft notice is in ibid., n.p., Königsberg, 29 Dec. 1871.

39. The Heubuden leadership's petitions on Dyck's behalf document this sequence of events. They in turn got their information from letters sent to the family by friends in Berlin, ibid., n.p., Koczelitzki, 7 May and 5 June, 1872. In addition Cavalry General Prince August of Württemburg reported on the matter at the emperor's request, ibid., 3 Sept. 1872. The sequence of events, the military's reaction, and the stated goal of breaking an individual's will bear a resemblance to the treatment of Mennonites in the United States when the draft was imposed during World War I, Gerlof Homan, American Mennonites and the Great War, 1914-1918 (Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1994), 99-134.

40. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., Berlin, 13 Nov. 1872. Every Mennonite petition in this case was turned down. A later report mentioned a Mennonite kept under "close confinement" for refusing to wear a side arm. His health gave way under this punishment, qualifying him for release as unfit for duty. Dyck is not mentioned by name, but the case described matches his, Barclay, Inner Life , 619.

41. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., Koczelitzki, 5 June 1872. This petition marked the end of Penner's cooperation with Elder David Ewert of Tragheimerweide, whose name does not appear on any subsequent petitions. Elder Johann Andreas was a lame duck by this point. Elder Johann Wiebe emigrated to Russia in 1872, Jakob Mannhardt, "Können und dürfen wir Mennoniten der von dem Staate geforderten Wehrpflicht genügen?" Mennonitische Blätter, 19, no. 7 (Sept. 1872), 46.

42. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., Berlin, 16 Sept. 1873.

43. On the role of state power in the Kulturkampf, see Margaret Anderson, Windthorst: A Political Biography (New York: Clarendon Press, 1981), 7-8.

44. Or Jews. For the liberals' theological rationale to press Jews to assimilate, see Uriel Tal, Christians and Jews in Germany. Religion, Politics, and Ideology in the Second Reich, 1870-1914 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975), 160-76. On liberal intolerance in general, see Wolfgang Altgeld, Katholizismus, Protestantism, Judentum. Über religiös begründete Gegensätze und nationalreligiöse Ideen in der Geschichte des deutschen Nationalismus (Mainz: Matthias Grünwald Verlag, 1992), 195-211. A good recent overview of the Kulturkampf is Ronald Ross, The Failure of Bismarck's Kulturkampf. Catholicism and State Power in Imperial Germany, 1871-1887 (Washington, D. C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1998).

45. The Ministry of Culture forwarded two of Reimer's complaints to the Danzig District Government along with demands for investigation, GStA, HA I, Rep. 76, III, Sekt. 1, Abt. XIIIa, no. 2, vol. 10, fol. 319, 29 Dec. 1873 and ibid., vol. 11, fol. 56, 18 Feb. 1874.

46. A copy of the judgment of the appeals court in Marienwerder, from which this description of the events in the Heubuden church on June 7, 1874 was reconstructed, is in ibid., vol. 12, fols. 20-25r, 6 Febr. 1875. On the law in question, see Huber, Verfassungsgeschichte, 4:714.

47. GStA, HA I, Rep. 76, III, Sekt. 1, Abt. XIIIa, no. 2, vol. 11, fol. 114, 1 Sept. 1874.

48. Ibid., vol. 12, fol. 26r.

49. The 1864 figures are cited on page 3 of the traditionalist petition of 1869, GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., 4 March 1869. The 1874 figure comes from a government report in GStA, HA I, Rep. 76, III, Sekt. 1, Abt. XIIIa, no. 2, vol. 11, fol. 31v.

50. Anna Claassen, "Mennonites at Beatrice, Nebraska, 1876-1926," in God's Love in Action. The Mennonite Community of Beatrice, Nebraska, 1876-1976, edited by Joanne Zerger Janzen (North Newton, Kans.: Mennonite Press, 1978), 16, noted the arrival of 132 Prussian families in Beatrice, Nebraska. John D. Thiesen, Prussian Roots, Kansas Branches. A History of First Mennonite Church of Newton (Newton, Kans.: Historical Commission of First Mennonite Church, 1986), 18-21, suggested at most 20 families from Prussia settled in Newton, Kansas. Perhaps an additional 20-25 families settled near Whitewater, Kansas, W. H. D. "Emmaus Mennonite Church," Mennonite Encyclopedia (ME), 4 vols. (Scottdale, Pa.: Mennonite Publishing House, 1955-9), 2:204, and Cornelius J. Dyck, "Zion Mennonite Church," ME, 4:1031-2. Assuming a family size of four or five, roughly 7-900 Mennonites left Prussia for America.

51. A Mennonite colony on the Volga, Alexandertal, opened in 1860. One hundred families, mostly from Prussia, eventually settled here, Berhard Harder, Alexandertal. Die Geschichte der letzten deutschen Stammsiedlung im Rußland (Berlin: Selbstverlag, n.d.), 93-4.

52. GStA, HA I, Rep. 77, Tit. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., Danzig, 23 May 1870. That year 158 of 8,258 Mennonites left, 27 of them were draft age.

53. David Goerz, "Nachruf für Wilhelm Ewert," Christlicher Bundesbote 6, no. 14 (July 15, 1887): 5.

54. Bartel, "Beschreibung," 77-78.

55. Harry Loewen, "A House Divided: Russian Mennonite Nonresistance and Emigration in the 1870s," in Mennonites in Russia. Essays in Honour of Gerhard Lohrenz, edited by John Friesen (Winnipeg: Canadian Mennonite Bible College, 1989), 127.

56. Leonhard Sudermann, Eine Deputationsreise von Rußland nach Amerika (Elkhart: Mennonitische Verlagshandlung, 1897), 7.

57. "Nachricht," Mennonitische Blätter 17, no. 2 (Febr. 1870): 16.

58. Horst Rößler, "Massenexodus: die Neue Welt des 19. Jahrhunderts," in Deutsche im Ausland - Fremde in Deutschland. Migration in Geschichte und Gegenwart, edited by Klaus Bade (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1992), 149-50.

59. Gustav E. Reimer and G. R. Gaeddert, Exiled by the Czar. Cornelius Jansen and the Great Mennonite Migration, 1874 (Newton, Kans.: Mennonite Publication Office, 1956), 42. On the importance of family ties and letters from family in America in this phase of German emigration, see Rößler, "Massenexodus," 155-7.

60. GStA, HA I, Rep. 332t, no. 5, vol. 2, n.p., 29 Dec. 1872. The government was obviously monitoring Penner's mail, as a copy of this letter ended up in Berlin.

61. Reimer and Gaeddert, Exiled by the Czar, 1-52; Loewen, "A House Divided," 133-5.

62. This trip is described in Sudermann, Deputationsreise.

63. For recent treatments of this larger migration see Theron Schlabach, Peace, Faith, Nation. Mennonites and Amish in Nineteenth-Century America (Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1988), 231-294 and Loewen, "A House Divided," 127-143. Only the developments that pertain to the Prussian part of this larger movement are followed here.

64. One such session held on 14 Sept. 1873 in the Heubuden church was reported in Mennonitische Blätter 20, no. 7 (October 1873): 56. See also W. C. Andreas, "Highlights and Sidelights of the Mennonites in Beatrice," Mennonite Life 1, no. 3 (July 1946), 21.

65. Reimer and Gaeddert, Exiled by the Czar, 72-9, 98-100.

66. Mennonite Library and Archives (MLA), Bethel College, North Newton, Kans., Wilhelm Ewert Collection, MS-6, Folder 1, "Kurze Notizen bezüglich der Auswanderung in 1874," 6.

67. Ray N. Funk, ed., Bruderthal, 1873-1964 (Hillsboro, KS: Bruderthal Mennonite Church, 1964), 3-6. Wilhelm Ewert, "Chronik über die Entstehung dieser Gemeinde (Bruderthal)," Gemeindebuch der Gemeinde zu Bruderthal, MLA, 1-3.

68. Peter Dyck, "Beschreibung meine Auswanderung nach Amerika, 1876," Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 11 (1954): 43-4. Gertrude Penner and Peter Jansen were married in 1877, Reimer and Gaeddert, Exiled by the Czar, 124-9.

69. Hermann Gottlieb Mannhardt, Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde: Ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569-1919 (Danzig: Selbstverlag der Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 1919), 173.

70. Ernest Claassen, et al., History of the Emmaus Mennonite Church (Hillsboro, KS: M. B. Publishing House, 1978), 46.

71. Reimer and Gaddert, Exiled by the Czar, 124-6.

72. Ibid., 118-9.

73. Claassen, et al., Emmaus, 52-3.

74. Ibid., 43,61; Cornelius Krahn, "Leonhard Sudermann," ME, 4:653.

75. Ronald Andres, et al., Centennial Reflections: Zion 100 (Elbing, KS: Zion Mennonite Church, 1983), 13-14.

76. The secondary sources vary significantly on the numbers in both groups. No study has treated the arrival of the Prussian Mennonite as a single movement, see Claassen, et al., Emmaus, 46-7; Zerger Janzen, ed., God's Love in Action," 12-16; Funk, ed., Bruderthal, 3-6; and Thiesen, Prussian Roots, 17-18.

77. Beatrice Express, November 27, December 21, December 28, 1876.

78. This communion set is now part of the permanent exhibit of Kauffman Museum in North Newton, Kansas.

79. Driedger, "Heubuden," ML, 2:311. Adalbert Goertz, "Warnau," ML, 4:468.

80. Thiesen, Prussian Roots, 17-23, 122.

81. Ibid., 48-9, 74-7, 126-7; Zerger Janzen, ed., God's Love in Action, 34-5, 71, 82; Andres, et al., Zion 100, 45-6.