March 2003

vol. 58 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2003

vol. 58 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Mary Sprunger is associate professor of history at Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, Virginia.

In August 2002, the play Jordan's Stormy Banks by Elizabeth Beachy debuted in Harrisonburg, Virginia, treating residents and visitors of the Shenandoah Valley to a story of tough choices and faithfulness during a war that cut through families, farms, and congregations. In the Midwest, the dramatic American Mennonite peace story revolves around World War One and the experiences of conscientious objectors in military camps and prisons. In Virginia, the pivotal experience for Mennonites was the Civil War. The Shenandoah Valley was the site of numerous battles as Confederate and Union troops marched up and down the so-called "Valley Pike" (today U.S. Highway 11 or Interstate 81). Mennonites and Brethren faced difficult choices in the midst of war, such as how to vote in the 1861 state-wide referendum on whether or not Virginia should secede from the Union. Even more challenging and divisive was how to deal with conscription into the Confederate army. Options included full participation in the Confederate forces, joining the army but refusing to use a weapon, or flight: a number of Mennonites and Brethren tried to make their way through the mountains to West Virginia (on the Union side) and then on to Pennsylvania. Some were caught and imprisoned before they completed the thirty-mile trip to safety. Elder John Kline, a vocal advocate for conscientious objection, is revered today as a Brethren martyr because he was murdered in 1864 for his challenges to Confederate conscription. As agricultural producers in the breadbasket of the confederacy, Mennonites and Brethren were also on the receiving end of Union General Sheridan's 1864 campaign of destruction, known locally as "the Burning," that razed barns, mills, and crops. (1)

The new Valley Brethren-Mennonite Heritage Center, an emerging joint venture between the two historic peace churches of the Shenandoah Valley, commissioned Jordan's Stormy Banks. Only in the last several decades have Mennonites and Brethren there started to work together on various projects. This center represents a major leap forward in that cooperation. The goal is a museum that will interpret the beliefs, practices, and histories, and help to sharpen the identity of Virginia Mennonites and Brethren. One hope is to contribute an alternative peace story to the Civil War narrative so prominent in the Shenandoah Valley. Commissioning the play was a way to publicize the purpose of the Heritage Center and work at shaping the story. According to Al Keim, director of the center, "We were amazed by the positive response to the play. It seems to have met a need, a kind of definition of what Mennonites and Brethren are and stand for."

Jordan's Stormy Banks is an impressive first-time effort for playwright Beachy, an Eastern Mennonite University theater graduate and Masters of Fine Arts student at Regent University in Virginia Beach. The subject matter almost requires a predictable plot. The drama centers around one family, the Showalters (intentionally rather generic so that they could be either Mennonite or Brethren). Conveniently, there are a variety of responses to military activity embedded in this one family, which provides the dramatic tension. Son Christian chooses to fight for the Confederacy while his brother Gabriel, a conscientious objector, is jailed for attempting to flee north. Son-in-law Reuben Herr, married to daughter Edith, dons a uniform but does not carry a weapon, and the love interest of a younger sister makes it safely to Pennsylvania. The main character is daughter Maria, played wonderfully by Kirsten Beachy (sister of the playwright). A young widow and mother, Maria is strong, brave, spirited, and resourceful. In one scene she serves pie to Union soldiers, successfully distracting them from their search for horses hidden on her farm. This scene is based loosely on a story from Beachy's family. The play climaxes when Union troops overrun the Valley: Reuben and Edith's farm is ransacked, Maria is burned when her farm is set ablaze, and Christian faces a showdown in the family kitchen with a Union soldier. Her play captures well the complicated experience of Mennonites and Brethren during the Civil War in a way that entertains, informs, and even inspires.

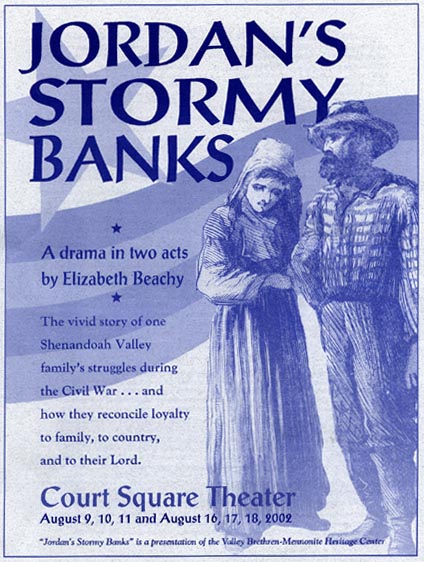

A union solder invades the Herr household and threatens Edith

(Sarah Mumbauer)

Issues of community surface in the play. A busy-body neighbor, unsympathetic to nonresistance, added some tension and humor to the plot, although the portrayal came across as a caricature. Nevertheless, her neighborly intervention highlighted the relationship to the local community during a time of war. Her suspicions of disloyalty on the part of Mennonites and Brethren and the lack of understanding for their pacifist position created hard feelings and even pain between neighbors previously on good terms. The importance of the other community in the play, the church, is woven throughout the drama via a group of soberly-dressed congregants singing hymns off to one side of the stage. Appropriately, most of the music comes from The Harmonia Sacra, a popular nineteenth-century songbook published by Virginian Mennonite Joseph Funk, with some new arrangements by musical director Matthew Hunsberger.

Maria (Kirstin Beachy) feeds her homemade pie to Union soldiers

Beachy first began writing the play as a series of "loosely connected vignettes" along the lines of Quilters. This has been a form typical of early Mennonite drama in the early 1970s, a style that tends to lessen the emotional impact on the audience. (2) Says Beachy, "After I'd written a number of them, however, I started to see that it needed more backbone, and began to string them together using the family as the connecting link." The result was something reminiscent of The Blowing and the Bending, written in 1973 by James Juhnke and J. Harold Moyer, which Beachy has never read nor seen. Written at the end of the Vietnam War era, the play focused on a Kansas Mennonite farm family as it struggled with threats from the community about not buying war bonds and making difficult choices about how to respond to the draft. Their German ancestry magnified the problems, as non-Mennonite neighbors viewed them as disloyal to the United States. (3) Mennonite drama commissioned by institutions, particularly that from the 1960s and early 1970s, has been characterized as "literal, didactic, self-congratulatory and uplifting." (4) While perhaps necessarily somewhat didactic, Beachy's script has moved beyond the purely self-congratulatory and uplifting by introducing complexity and ambiguity into the play.

The Showalter family comes together at the end of the play. In the

front are (left to right)

siblings Maria, Christian (Matthew

Hunsberger), Gabriel (Hans Burkholder).

In the back are father

Lewis Showalter (Paul Roth), mother Abigail (Karen

Moshier-

Shenk), daughter Edith Herr (Sarah Mumbauer), son-in-law Reuben

Herr

(Shannon Dove), and daughter Sarah Showalter (Rosanna

Nafziger).

Directed by Paul Hildebrand (drama professor at Eastern Mennonite University) and held at Court Square Theater in downtown Harrisonburg, the show played to sell-out crowds and extra performances had to be added during the two-weekend run. Noticeably absent in the audience, with only few exceptions, were the younger generations. In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and in our present context of uncertainty and war, now is the time to expose Mennonite and Brethren young people to stories of peace from their own histories. This play was a good reminder of the hard choices that members of historic peace churches have always faced when their countries are at war. Especially relevant themes of the play include: the gray areas that arise when one's own farm and home is being attacked; the community tensions that result when some opt out of the typical patriotic response; and the bravery and steadfastness of Mennonites and Brethren who remained true to their understanding of Christian pacifism. Keim's assessment of the play is that it "has a kind of universal quality about it; the resolution of whether to enlist in the war or not and the moral ambiguities connected with that decision is a timeless question, present in any age, and there are no cookie-cutter answers."

Since seeing the debut production, Beachy has substantially rewritten the play. There will be several chances to see the revised version of the play in the summer of 2003, when Jordan's Stormy Banks goes on tour to Harrisonburg, Virginia (June 6-8, 13-15); Lancaster, Pennsylvania (June 19-22, 26-29); and Atlanta, Georgia, for the Mennonite Church USA Assembly (July 4-7).

1. For Mennonites and the Civil War, see Samuel Horst, Mennonites and the Confederacy: A Study in Civil War Pacifism (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1962); and Jacob R. Hildebrand, A Mennonite Journal, 1862-1865: A Father's Account of the Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley, compiled by John R. Hildebrand (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1996).

2. Anna Juhnke, "North American Mennonite Playwrights, 1980-1996," Mennonite Quarterly Review 71 (1997): 43-44.

3. For more on The Blowing and the Bending, see Juhnke 54-55.

4. Paraphrase of Ervin Beck in Juhnke 43.