March 2003

vol. 58 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2003

vol. 58 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Since 1989, Katherine Bartel has been teaching art at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois, as well as exhibiting art widely. At EIU, she has been Associate Professor in the Art Department, teaching in Foundation Studies as well as serving on the Graduate Faculty, since 1996. She taught in the Bethel College art department from 1986-1989, and in the Hesston College art department from 1984-1985, after earning an MFA from Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville. She graduated from Bluffton College with a double major in art and social work in 1979.

History is a combination of photographs, documents, and memory. All of these sources originate from a particular viewpoint, a particular time. Historians would say that there is no such thing as an "objective" account. As an artist, I have taken my personal viewpoint one step farther, expressing not the factual narrative as I remember it but the cultural identity it has imprinted on me. We are the sum of the legacy of our ancestors and the person we choose to become. Embedded in the inheritance are values, beliefs, a version of what is normal, and many rich relationships with people. We may decide to live differently once we are grown, but the foundation is already laid.

Memory is different from narrative. Time becomes more fluid, more layered. Events are synthesized across the years, people appear at multiple ages. Some images are still crisp and detailed, others are blurred and faded. All of the senses can recall these things-the smell of zwieback baking, the touch of a baby's skin, the sound of congregational singing, the taste of peppernuts at Christmas, the way wheat bends in the wind. The past and present intersect as familiar objects leave clues about where they started. Time dissolves as the past takes over our consciousness momentarily.

Living close to tradition is warm, but it can also filter one's judgement. I have been away from Kansas for 13 years, living among the rest of the world. This distance has allowed me to be nostalgic at times, but I have also been able to sort out the wheat and the chaff. The place I remember was not perfect. When church members ask visitors who their parents are, our guests feel like outsiders. But when I participated in a recent peace march, it was because I know war is wrong. As an urban professional, I do not grow my own vegetables or bake zwieback. This is a loss in the quality of life, but my calling is greater now. My work as an artist brings me closer to God and community.

2001

video installation with table, chairs, wheat, etc.

My purpose is to recreate memories, which occupy a slightly different landscape than real life. In "Interlude," the video is in slow motion, and the soundtrack's voices sound as if they are in the distance. I wanted to create the sensation a child might have lying on the kitchen floor while the adults are talking. The voices are speaking Low German, of course; they list what they ate when they were children. More distinct are the wind and crickets, the sounds I remember from Kansas.

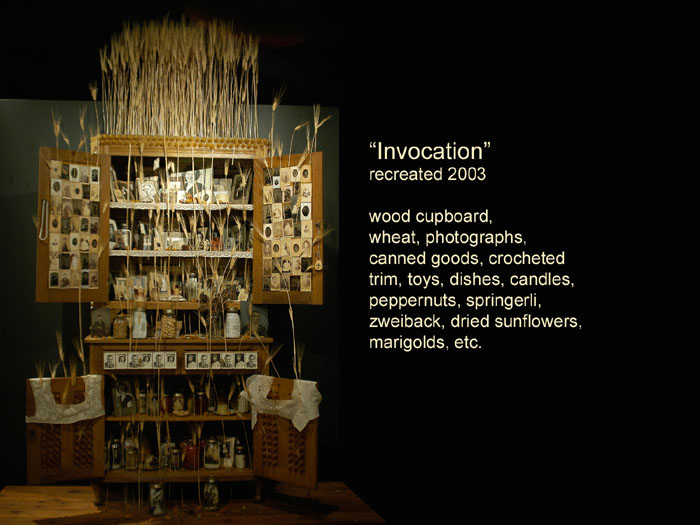

originally done in 1998, recreated in 2003

found materials in a wood cupboard

Other traditions create altars. Mexican Catholics display home altars with photographs of loved ones, food offerings, candles, and marigolds. Haitian voudou altars hold precious objects recycled from the trash of white people, bottles of rum, candles, and offerings. These installations are used for religious observances. When the Anabaptists rejected Catholicism, the richness of visual icons was lost. The values of frugality and simplicity served the struggle to survive hard times. In comparison, visual art was regarded as a frivolous pursuit. As I looked at other cultures, I felt the absence of iconography in our tradition. I wondered what a Mennonite altar would look like, so I created my own.

Included here are the family photos I have seen in so many homes, on mantles and pianos. Our holidays call for special decorations. Children leave traces of their lives among the furnishings. We practice the rituals of singing hymns, cooking certain foods, sewing and crochet, reading favorite Bible passages, and praying.

The traditional foods that are laid out for faspa or holiday gatherings have their own aesthetic standards. Springerli are laborious to make and always decorated with images; women apologize if the mold's impressions are imperfect. Zwieback must be divided into a double roll and stand upright to be "correct." Peppernuts can only be a certain, uniform size. Canned goods should be an attractive color with the food cut into pleasing segments.

Mennonites do have cultural icons, even altars. Instead of marigolds, we have wheat and sunflowers. Instead of rum, we have zwieback. In spite of our practicality, we are spiritual beings and could not live without art.

2002-2003

video installation with sink, cabinet, produce, etc.

We all come from agricultural roots, thus the Bible has many metaphorical references to planting and harvest. In contemporary time, most of us are no longer directly connected to living off the land. A few of us have gardens, and we plant token amounts of flowers and vegetables. My father is still a farmer at heart, planting not one but several ambitious gardens. We never had to buy vegetables at any time of the year. His way of nurturing and providing for us was to grow things. In doing so he was also nurtured by the memory of helping his own mother in the garden when he was a child. (He lost his mother at the age of 13.) Thus gardening has become not only a way of storing up for the future, but a link to the past. Agriculture is our foundation, watching the crops marks the seasons. Here, the cycle of growing is the cycle of life, a spiritual journey.

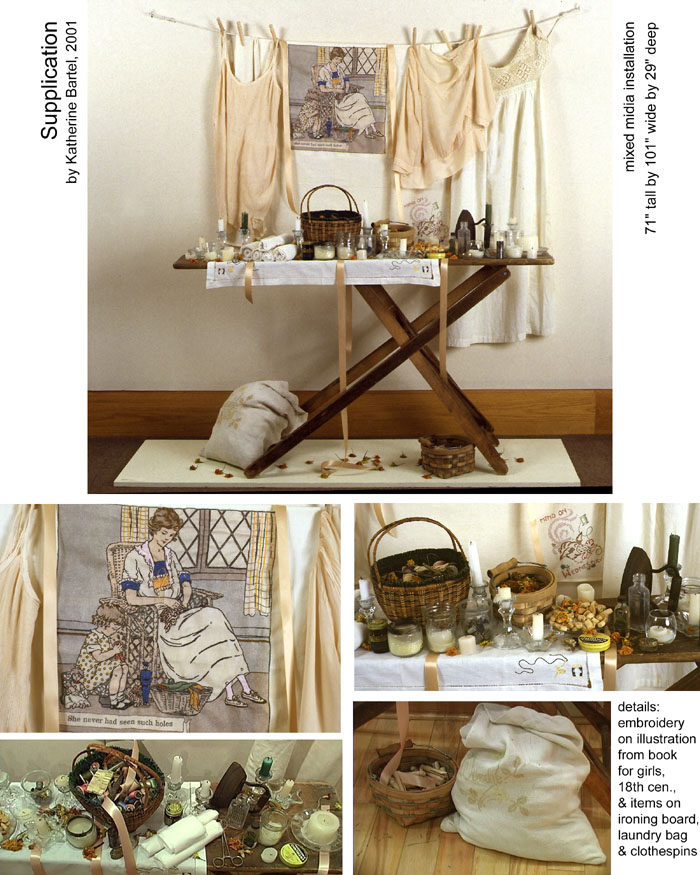

2001

mixed media installation

An old wooden ironing board holds a home altar, made up of elements women used in caring for their families. The tea towel that hangs above it on the wash line as an illustration from a 19th century book for girls, showing how we learn our roles. It is Wednesday, the day for "mending." Women are no longer expected to darn socks in a time when we can buy new ones at Wal-Mart, but socks without your mother's stitches are not the same. Neither is a bout with the flu the same without her chicken soup. Mothers are our nurses, responsible for healing. Until my mother died in 1994, my sister still called her for a long distance diagnosis whenever she was ill.