Grant Stoltzfus and Ruth Brunk Stoltzfus in 1959. (Credit: Mennonite Publishing House)

June 2003

vol. 58 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2003

vol. 58 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

Dick saw her first.

"I've met the most extraordinary woman," he said. "She's like one of those old Quaker women you see at protests and peace marches - strong character, strong convictions. You've got to meet her!"

It took a while for me to share my husband's enthusiasm for Ruth Brunk Stoltzfus. Dick had made connections with Grant Stoltzfus and other Mennonite historians soon after we moved to the Harrisonburg area in 1972, but I was at home with our two little boys and knew Grant and Ruth only second-hand, through Dick's reports, though once I heard them speak briefly at a public meeting.

Grant Stoltzfus and Ruth Brunk Stoltzfus in 1959. (Credit: Mennonite Publishing House)

When Grant died in July 1974, Dick and I attended the memorial service - our first experience of a service in a Mennonite church. We sat in the balcony, with a clear view of the family sitting on the front pews. What I remember most vividly from that evening was feeling amazed when Ruth rose to address the congregation from her pew, speaking at length about her marriage, even telling an anecdote about an argument over an air conditioner.

A few months later Dick and I, our two little boys, and our baby daughter began to attend Park View Mennonite Church regularly, and I soon came face to face with Ruth. It was in the church basement after Sunday school; I was carrying baby Sarah in my arms and Sam and Tom were fussing at each other behind me. I remember how tall she was, and feeling more than a little intimidated.

Another couple invited us to join one of the small fellowship groups at Park View that met weekly in homes for Bible study, personal sharing, and prayer. The group included Ruth, and at our very first meeting, she and I got into an argument. She said something about Billy Graham's support for the Vietnam War negating his Christian witness, and I challenged her. She disputed my point, and I disagreed with what she said. We went back and forth for several minutes without coming to agreement, and then she smiled and said, "I haven't had such a good time since Grant died!"

We were friends after that. In 1976 she was one of a small number of people I consulted about enrolling in the Master of Divinity program at Eastern Mennonite Seminary, and when I felt oppressed by the misogynist attitudes rampant at the seminary in those days, she encouraged me to continue my studies. In turn, I encouraged her to send her talks to the church press for publication. We began to meet weekly for breakfast, and over a restaurant meal we would, as she phrased it, "settle all the problems of the church and the world."

Our children adored her. When Tom was about five years old, he drew a picture of Park View Church with a tall stick figure in a skirt standing in front of the door - Ruth Stoltzfus, of course!

Stoltzfus family in 1959. Left to right: Kathie, Grant, Allen, Eugene, Helen, Ruth, Ruthie. (Credit: Mennonite Publishing House)

For me, too, Ruth was the symbol of the Mennonite Church. I was inspired by her bold public witness and moral certitude on issues of peace and justice. Her courage was a model for me, even when I didn't share her clarity of vision.

In those days Ruth had a full schedule of appointments, many of them involving travel. I was at home with three children, editing Park View's monthly newsletter, taking seminary classes part time, and writing stories and articles for publication. It was a natural next step in our relationship to collaborate on writing projects.

In the winter of 1978-79 Ruth was invited by the Women's Concerns Committee of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) to compile a report on the subject of "Women in a Speaking Ministry." It was, of course, a subject close to her heart, but she hardly had time to write her talks, she said. How could she take on such an assignment? Besides, she'd rather speak than write. "Let's do it together," I suggested, and we did. The report was published by MCC in February 1980.

The same thing happened a few years later, when the denominational women's organization asked Ruth to write their 1985-1986 annual devotional guide. Ruth was still recovering from cancer surgery and saving her energy for speaking appointments. But the topic WMSC was proposing was compelling - the Book of Ruth as a model for women's friendships. Ruth and I could enact the Ruth-Naomi relationship even as we collaborated on the devotional guide. Since I was in the middle of writing the Herald Press Story Bible series, it seemed natural for me to write the Bible commentary and for Ruth, with her many years' of experience in speaking to women's groups, to provide the discussion questions.

These were also the years that Ruth was strengthened in her sense that she should tell the story of her public ministry in print. Throughout her adult life, she had kept a journal and saved copies of every letter she ever wrote. She put her stories of her childhood and youth into paragraph form and labeled the notebook, "Blueberries and Briers," the working title for her autobiography. She paid a typist to transfer her writings onto the computer, and she made inquiries of the editors at Mennonite Publishing House, who expressed interest in a book of "stories of my years."

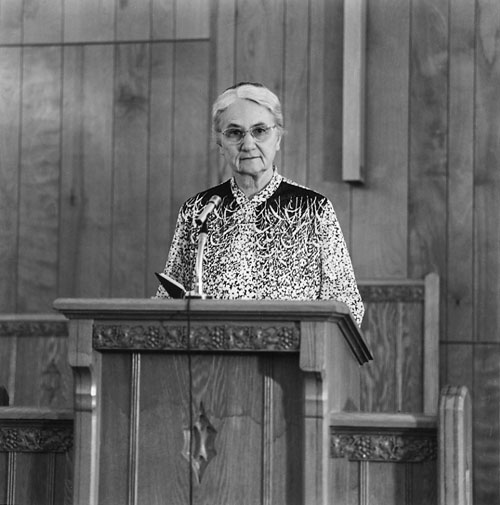

Ruth Brunk Stoltzfus in the pulpit. (Credit: Mennonite Publishing House)

At our weekly breakfast meetings she shared several versions of accounts of her childhood, youth, and the beginning of the Heart to Heart broadcast. But the volume of material was overwhelming; she said once that her grandson Reuben had estimated that she had 8,000 pages of autobiographical material on the computer.

In 1986 our family moved to northwest Ohio, but I didn't lose contact with Ruth. We bought a house in Bluffton, just a few miles from Pandora, where Ruth had served as interim pastor from September 1982 to June 1983. I visited the parsonage where Ruth had shoveled snow, and Grace Mennonite Church next door, where she had weathered the flag controversy.

When I came back to Virginia to visit my parents, Ruth and I would meet for breakfast, and the conversation nearly always turned to the book. Church and family responsibilities were so overwhelming, she said, that she had made a contingency plan: would I agree, that if she should die before completing the book, I would finish it, and her niece Emily would see the manuscript through publication? Of course I would.

In 1994 Dick and I moved to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and Ruth and I set up a schedule to meet regularly to work on the book. About once a month I would drive south down Interstate 81 and she would drive north, and we would meet at a Mennonite restaurant in Maryland. It soon became apparent that she wasn't making progress, and driving that far on the interstate was becoming increasingly difficult for her. In the summer of 1998 Ruth's children encouraged her to turn the project over to me for completion, pointing out how much she would enjoy seeing the final publication.

I was glad to help as a labor of love, but Ruth insisted on paying my expenses and an hourly rate based on what I was paid by Mennonite Church General Board as editor of Voice, the monthly magazine of the denominational women's organization.

How do you tell the story of a life? How do you create a narrative that communicates the truth of another person's personality and character? How do you speak in another person's voice with integrity?

The first step was for Ruth to turn over her notebooks to me, and then her son Eugene put on a ZIP disk the 8,000 pages of journal notes and letters Ruth had selected as the raw material for the book. I arranged the stories into chapters and subchapters and the sentences into paragraphs. But the record on Eugene's ZIP left gaps. Ruth's memory was failing. How could I create a narrative when I didn't know what had been left out?

Ruth readily agreed to give me access to whatever I needed, and I drove to Harrisonburg and filled up the trunk and back seat of my Honda with journals, notebooks, newsletters, and boxes of family papers. I assured her that sensitive family material would not be made public, but explained again that I needed more information than what was on the computer or even what would finally be published.

The missing pieces began to fall into place. Letters to Frances Dean Strickland filled out the picture of Ruth the teen-age missionary and Ruth the young bride. Newsletters from the Civilian Public Service camp displayed unexpected playfulness. The Heart to Heart newsletter gave me a sense of the community that produced and listened to the broadcast.

The hardest part was deciding what to leave out, especially in the later chapters, because Ruth had so much documentation on her pastorates and ordination. How could I do justice to the story without wearying the reader? How could I keep the narrative energy flowing without omitting significant details? And which details were significant? Ruth's own long-windedness was the subject of more than one family story.

In one of the boxes of family letters and keepsakes I found a copy of her father's story about his parents, told in verse as well as prose. Like many others, I was enchanted by the drama and pathos of grandmother Susanna losing and then finding grandfather Henry. That tale not only helped form Ruth's sense of family and self, it has become part of the larger Mennonite community's heritage, having been retold in several collections of stories and on stage by Ruth's daughter Helen.

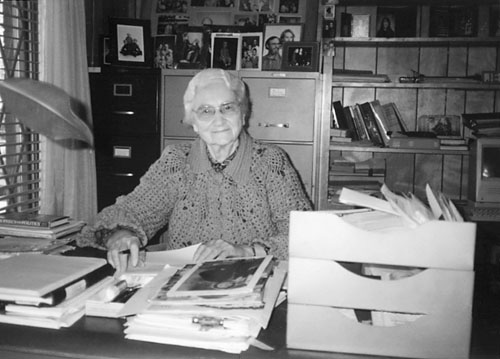

Ruth Brunk Stoltzfus at her desk in 1993. (Credit: Mennonite Publishing House)

Like her father, Ruth broke into verse when she was deeply moved, and so I decided to include the full text of several of her poems, even the long "Personal Psalm of Praise, Petition, and Commitment."

The rationale for including Helen's story of her father's death was different. Helen's account described Grant's personality more vividly than anything I found in Ruth's journals or heard from her in conversation, and Ruth's story seemed incomplete without it.

Ruth's strong personality and vision of her life and mission were in place early. I looked for doubt and reflection, and found unwavering focus. As she makes clear in her preface, Ruth's self-understanding was of a woman on a journey, a pilgrim overcoming obstacles in order to fulfill the destiny the Lord had prepared for her. That sense of purpose kept her from self-doubt when others questioned her breaking out of the traditional woman's role that confined her spirit.

The pain in her life came from the sense of failure when her family didn't match the idealized picture she described of her childhood home, an ideal she taught others to strive for. It was easier for her to talk about Allen's agnosticism than about Grant's depression. She wasn't reflective, but her spiritual integrity led her to an honesty about herself that I found endearing. Christian humility leavened family pride.

Her faith in the Lord never wavered. When I visited her in the hospital in Charlottesville after her surgery for colon cancer, I found her lying flat on her back, speaking about her hope for a reunion in heaven with her departed dear ones, and her confidence in her Savior.

Ruth was never girlish, but she was always a lady. She had beautiful Southern manners, rooted in a genuine concern for other people. Even when she was in conflict with another person's position on an issue, she never failed in graciousness, never made her criticism personal. It was a source of pride and comfort to her that people in Pandora who differed from her about displaying the flag in church accepted her as their pastor.

She was a loyal friend, generous in praise and quick to share credit. Years after she had a photographer take pictures of our son Tom to update her family life newspaper ads, she would send him a dollar bill as a "modeling fee" every time she used one of the photos. She charged way below market price for the apartments she rented to students. Her pleasure was in helping people, befriending international students, serving her God by serving others.

There are missing pieces. The written record does not communicate the sense of fun we had over those breakfast conversations. The careful record of accounts received and sermons preached doesn't tell the full story of debts forgiven, hospitality extended, prayers uttered for friends and strangers, and the sheer personal force of that unique and extraordinary woman, my friend Ruth.