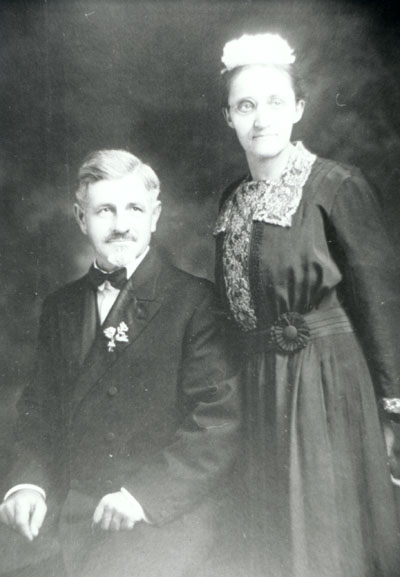

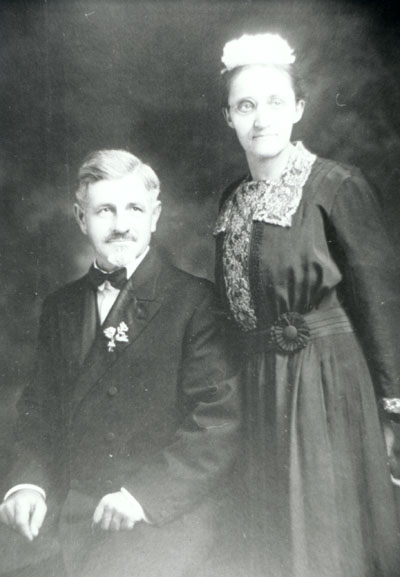

Bernhard W. Harder and Minna (Wiebe) Harder, 1925

September 2002

vol. 57 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

September 2002

vol. 57 no. 3

Back to Table of Contents

Link to interview audio file (mp3, 20mb, 22 minutes)

Bernhard W. Harder (1877-1970) in 1918 was a Mennonite farmer in Butler County, Kansas, and pastor of the Emmaus Mennonite Church. During the war a mob from the town of Whitewater came to his farm home to force him to fly an American flag on his farmstead. Mark Unruh’s article in this issue examines the meanings of the oral memory of this event among Kansas Mennonites.

Bernhard W. Harder and Minna (Wiebe) Harder, 1925

Harder’s son, Bernard Goethe Harder (1902-1982), was present with his father at the time of the incident. The son, known as B. G. Harder, was sixteen years old at the time. In 1974, fifty-six years later, when B. G. was seventy-two years old, he told the story in a tape-recorded interview for the Schowalter Oral History Project at Bethel College. The interview is the only surviving eyewitness account of the event. Another account, with additional details, is in a taped interview with Ernest Claassen, a Mennonite farmer who lived nearby and who was also a member of the Emmaus Mennonite Church. The tapes are in the Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel College.

In this issue we present both the audio record and the written text of parts of the 1974 interview with B. G. Harder. These segments do not mention the issue of war bonds. The Emmaus congregation was divided on that issue. Bernhard Harder, the pastor, did purchase some bonds, and counseled church members to do so. The mob that visited his farm obviously did not consider war bond purchases to be sufficient evidence of patriotism. Gustav Harder, mentioned in the interview segment, was Bernard Harder’s uncle, and elder of the Emmaus congregation.

Some members of the Emmaus congregation, including Henry H. Wiebe and John Regier, refused to purchase bonds. On the war bond question, see the article by Margaret Entz, “War Bond Drives and the Kansas Mennonite Response,” Mennonite Life, September 1975, 4-9. An article that tells the Harder flag incident in the context of mob violence in 1918 is by James C. Juhnke, “Mob Violence and Kansas Mennonites in 1918,” The Kansas Historical Quarterly, Autumn 1977, 334-350.

Interviewer: Well, how did this whole thing come about? Can you give a little background on that?

Harder: Well we were putting a roof on the hen house, built a hen house and there was kind of a, what do you call it, a rally or pep meeting, the army, American Legion was putting on kind of a patriotic meeting and a young fellow by the name of Frank Snorf was home on furlough.

Interviewer: Frank Snorf?

Harder: S-N-O-R-F

Interviewer: S-N-O-R-F

Harder: Frank Snorf . He’s just a very short fellow, lives two miles east of us. He come by, he said, “When I come back I want to see a flag hanging here at the house.” Well, I didn’t think too much of it. And he was a little windy, you know.

So we was on the hen house and my grandfather’s place is on the hill, just a little over a mile the way the bird flies. And we was on the roof there and I told Dad, “Why it looks like a funeral procession coming over the hill.” And he saw right away that’s the group from Whitewater. So we, we was putting on tar paper, you know, that’s sticky stuff, so we went in right quick and cleaned up and by that time they was—Well, they didn’t have as many cars as they do now, but I would judge twenty-five, thirty cars.

And when they had this pep meeting—or whatever you call it—in town, this Frank said, “All those that want to see something, follow me.” And he started out in the car and nobody knew where they were going. They just simply followed him. And quite a few business people and quite a few people in the neighborhood after a while came by and apologized that they had been there. They didn’t have no idea what Frank was demonstrating or where we were going or nothing. And so they came out here. And Dad was in the house already. And one fellow by the name of Thomas—he was known as kind of a hot head. He lived, oh, six or seven miles northeast, was known as kind of a hothead in the neighborhood and—

Interviewer: Was Thomas his last name or his first name?

Harder: Last name. I don’t know his first name. I don’t remember that. And so Dad came out of the house. And I tell you, they were—they were mad. And came up with the flag and said, “Now you nail this flag up here.” And so why he nailed it up there. And I was just standing beside the house there. And some of the people were just awful mad. Didn’t know what would happen.

Interviewer: Where did he nail the flag?

Harder: On the porch. On the stair where you walk into the porch, onto the porch.

Interviewer: On the top?

Harder: Right under the roof. So it would hang down, oh, about that far down. Dad nailed it there. And I’m not sure, did he say, “Let’s sing ‘America’ or ‘Star Spangled Banner’?” I don’t know which one. And you could just feel it that the sentiment changed right now. Instead of being so mad and hot they just changed right now. And then they said, “Now, we want that flag to stay there.” Well, Dad said, “What if the wind whips it off, it’s loose that way? You know you’re really not supposed to leave a flag out all the time, are you?”

Interviewer: Yeah. You’re supposed to take it down at nighttime.

Harder: Well, these fellows said, “No, that flag stays there.”

Interviewer: All night too?

Harder: Stays there. Dad said, “Well, what if the wind whips it and tears it?” “You put another one up.” There were no questions asked. So I don’t recall that we put another one up. You know they stay a long time. I mean they last quite a while.

Interviewer: Yeah. What happened to the flag? Do you still have the flag?

Harder: Oh, no. The wind whipped that all to pieces, you know. So on the way they stopped, or wanted to stop, at this man. And some said, “He’s an older man and let’s leave him alone.”

Interviewer: Gustav Harder?

Harder: That’s him. Yeah. And I don’t know if they stopped there. I don’t think they did. See, in those days they talked of, and they did, some tarring and feathering. I don’t know if you know anything about that. They did some of that, and that’s what we were a little bit afraid of that might happen here.

. . . . .

Interviewer: When they sang, or when your father suggested that they sing that song, where did he learn that song?

Harder: Well, you see, he was born here and he went to Brainerd school.

Interviewer: He probably learned it in school.

Harder: Yeah. And then he went, he was in the Bethel Academy a year or two. And then he went to Emporia and he taught school.

Interviewer: He taught school around here?

Harder: Yeah. You see, we had, we went to Brainerd school one year or two years, maybe two or three years. And then we had a German school west of Brainerd and we had one west of our church. And about every two or three years we would go to that school. But reading, arithmetic, I thought there were three subjects that we carried from the district school . . . .

Interviewer: So your father taught German school then?

Harder: Yeah.

Interviewer: Did they sing more than one verse?

Harder: I don’t know and I should know which song they sang, but I don’t. But I know it was one of the patriotic.

Interviewer: When Allen Busenitz told me about this, he said that your father led out in the first verse of the song. And everybody sang along. But then he went on and sang three or four verses, and he knew all the verses.

Harder: Yeah, no doubt he did.

Interviewer: And that by the time he was done singing, the crowd was very embarrassed.

Harder: Yeah, and they started backing up, started to leave.

Interviewer: So that, you do remember that?

Harder: Yup. . . . .