Photo 1

June 2002

vol. 57 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2002

vol. 57 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

On September 17, 2001, while driving home, I heard an NPR interview with Suha Samhouri, "a typical New York woman in her mid-20s, except for the Hijab that covers her head." The previous week, reporter Rick Karr explained, when she drove to a shopping center, "she failed to recognize two women she'd known for years . . . because they weren't wearing Hijab." Samhouri herself reported, in the interview, "As I was walking towards my car, I just saw the tears roll down my eyes and I couldn't believe it. I was really shocked. . . . Just very unbelievable, someone, you know, having to change their beliefs, their ideas because of one or a group of really terrible people." And as I was driving, I, too, began crying. A week later I read, in a Newsweek article, "In Washington D.C., Muslim women have had hijab scarves snatched from their heads." (1) During September I heard other NPR interviews with young Muslim women in the U.S., for example, Amina Chaudary, a graduate student in public policy at George Washington University. Chaudary, who began wearing the scarf during high school and wore it when she was the captain of the varsity basketball team, said that it has now become "a target-verbal, physical, whatever-stares."

I became angry when I heard of such mistreatment and equally angry during local discussions treating a Muslim woman as an Other. Here in Evansville, Indiana, I attended a book discussion of Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women, (2) written by Geraldine Brooks, a Westerner--a foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal in the Middle East. Throughout most of this book, Brooks describes Western women's dress in positive images and Muslim women's dress (head and body coverings) in negative ones. For example, Brooks complains about a young Muslim woman's getting rid of her Western dress: Sahar "wrapped away" her curls "in a severe blue scarf" and replaced her "shapely dress" with "a dowdy sack. . .[;] she had crumpled her bright wings and folded herself into a dull cocoon" (p. 7). Elsewhere Brooks describes Muslim women's dress as "shapeless" (pp. 22, 63), "figure hiding" (p. 23), and "concealing" (p. 92). These outfits are compared pejoratively to the clothing of nuns, whom the author considers "fossil[s]" (pp. 10, 92), and to death and hell: the chador worn by the author to gain credibility at a press conference is a "black shroud" (p. 289), and the "360-degree black cloaks" worn by Saudi women "made them look, as Guy de Maupassant once wrote, 'like death out for a walk'" (p. 21). On one occasion the author, seeing "the black-cloaked figures" of women, feels as if she had been "locked up by mistake in some kind of convent from hell" (p. 19). In our group discussion of this book, other women, sharing Brooks's bias, asked, "How could they wear those clothes?" Outraged by their question, I wanted to leave the room.

Instinctively I placed myself in the position of Muslim women wearing distinctive clothing, especially as minority people in the U.S., not only when I listened to the radio or participated in a book discussion but also when I saw them in person. When, with other friends, I went to an open house at the local mosque and when I saw the local imam's wife at a civil rights luncheon, I identified more with the Muslim women, whether their heads were fully or partially covered by scarves, than with the other women accompanying me. Recently I recalled another moment perhaps ten years ago when, in a restroom on the University of Evansville campus, I was standing at the washbowl beside a Muslim woman wearing the hijab. I felt that I was in her place. In this identification, my intellectual recognition of the apparent oppression signified by prescribed coverings for women's heads and bodies was subordinated to my experiential connection with Muslim women.

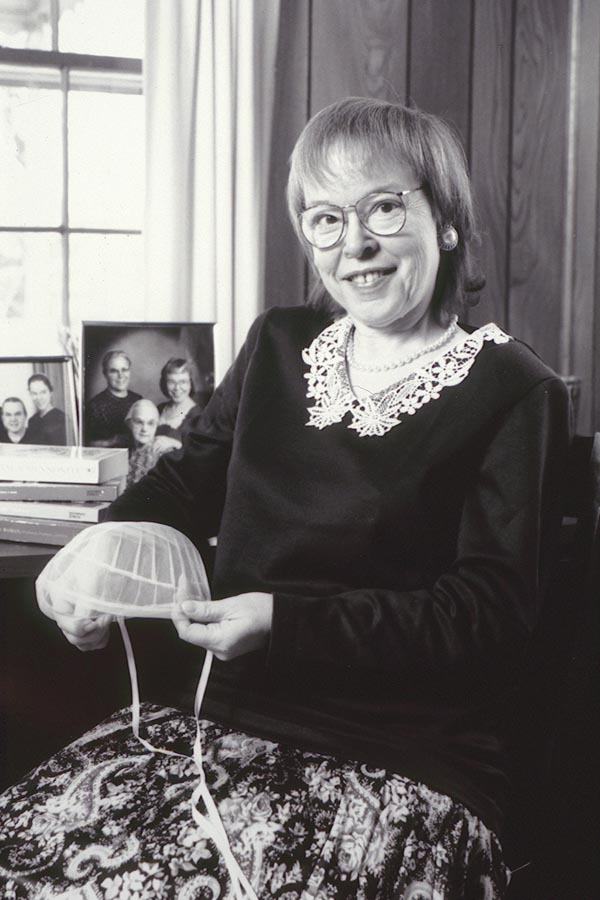

Photo 1

Because of the increased attention given to Muslim women's clothing after September 11, I began to revisit my experience with the Mennonite cap (head covering) and plain clothing, worn until I was 31 years old. During the past 19 years my earlier changes in cap/hair/clothing have often constituted the subject matter of my personal-experience essays designed to demonstrate my gradual acculturation. In those essays I never set out to ridicule my cap and plain clothes; I just attempted to show the changes. Photograph #1 illustrates that phase of my writing: my treating the cap and the plain clothes as an artifact, something to be discussed. In that photograph, I am a spectator of my life, as shown by my holding the cap in my hands and by the family photographs in the background--one showing me in my plain clothes and the other, in my non-plain clothes. Now, however, I've begun to see my plain-clothes experiences in a new way.

Instead of concentrating on my acculturation, I'm now interested in looking closely at my "plain" period, especially at the ways in which, despite my different appearance, I was a normal person participating in activities in the dominant society. I sense that my objection to others' seeing Muslim head scarves and other clothing only as an instrument of oppression--as something to ridicule or seek to eradicate--derives from my plain-clothes past. Seeing the scarves and dresses, I recalled my own experiences not as an "other" but as a normal person.

Reminiscing prompted me to locate photographs taken when I was a plain-clothes student at Manor-Millersville High School (now Penn Manor) in Millersville, Pennsylvania, and a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. In appearance I had nothing in common with the other students in either place. However, I participated in life at both places; underneath the different hairstyle, the cap, and the plain dress, I was a human being who, in a public high school, shared with others in academic work and extracurricular activities and, in graduate school, again performed the usual academic work and socialized with other students. (3)

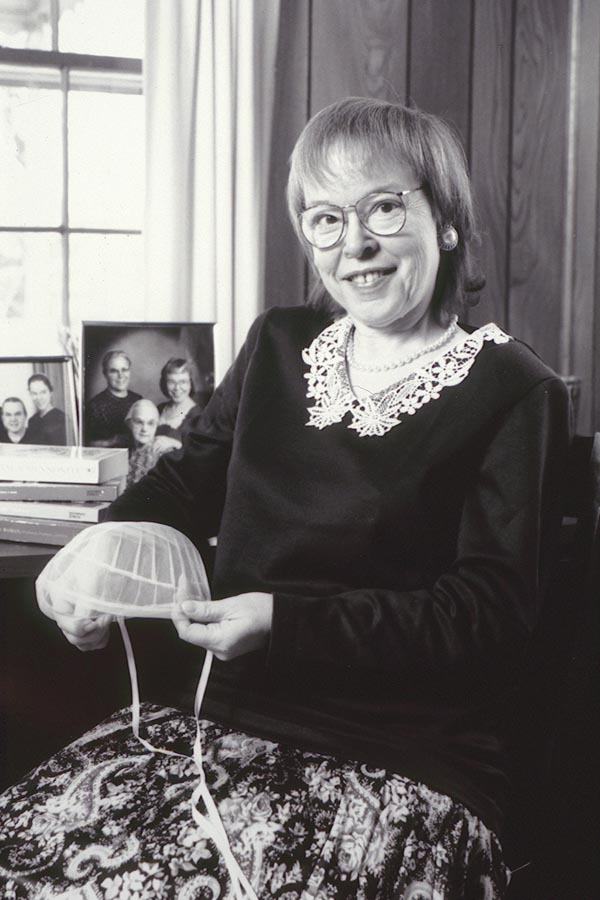

Photo 2

Throughout high school I not only went to classes but also engaged in extracurricular activities. And always I wore the cap, even when singing in Glee Club performances within and outside the school and while wearing a gym suit for physical education class. Never did anyone order me or even try to persuade me to take off the cap or to stop wearing the cape dress. Two photos illustrate my differences from other people but also my participation. Photo #2 shows that the high school girls, except for a few other plain-clothes Mennonites, had cut hair and curls, wore skirts and blouses (some with decorative bows), and white socks. However, I wore my hair pulled back in a bun, wore a cap with strings, a cape dress with no decoration, and black shoes and stockings. Clearly, I was different. However, that physical difference did not prohibit me from actively joining in high school life and even in gaining recognition as the editor of the school newspaper, Manor Hi-Lights. As the editor, I was seated in the center of the photo, with 26 other staff members around me.

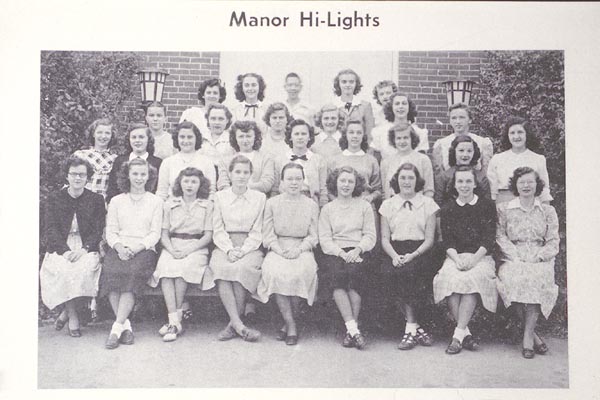

Photo 3

In the National Honor Society photo (#3) I again looked different. Other girls had cut hair and curls, wore skirts, blouses, scarves. I had long hair in a bun, wore a cap with strings, and wore a cape dress. But I participated sufficiently in high school life to be inducted into the National Honor Society, which emphasized scholarship, leadership, character, and service.

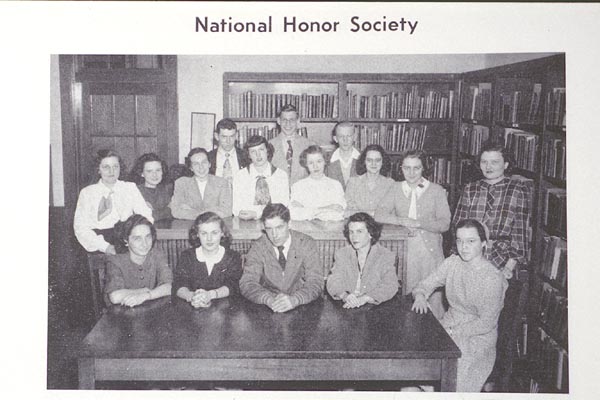

Photo 4

Photo 5

The next two photographs (#4 and #5) were taken on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia during my work on a master's degree. Although, of course, my life there, just as in the public high school, involved academic performance, these particular photographs illustrate that, despite my different appearance, I socialized with other graduate students in English. Again, I am distinguished from other female students by my hair worn in a bun and by my white cap. By this time in my life, the cap was smaller, more hair showed at the neck, and there was less difference between my dress and those worn by other young women. However, I was still different--in fact, the only University of Pennsylvania woman wearing a cap. But just as clearly, I became friends with other graduate students, both women and men. We often studied in the same section of the library, and we socialized outside of classes. Together we went to parties. Although I drank soft drinks when others drank alcohol, I was there--invited with other students.

By the time I taught at Bluffton College and then completed a Ph.D. at the University of Kansas, I no longer wore a cap and cape dress. However, during the previous 31 years of my life (except for periods as a student and a teacher at Eastern Mennonite College and a teacher at Belleville Mennonite High School [Pennsylvania]) I was accustomed to looking different from the people around me: in public grade school; public high school; the workplace (an advertising agency and a law office) during two years between high school and college and in Christmas and summer vacations; and graduate school during my master's degree studies. That difference, revealed in those five photos, became so internalized that, regardless of my agreement or disagreement with the reason for different clothing, I still identify with the persons wearing it. When something negative is said about them, especially women wearing religiously-prescribed clothing, I cringe--as if it were said about me. (4)

My witnessing the discrimination against Muslim women's head coverings and other clothing has profoundly affected me, without, however, leading me to romanticize either conservative Mennonite or Muslim women's experiences. Focusing less on my acculturation, now I am revisiting my experience with plain clothes, recapturing my engagement as a minority person in the dominant society. I remember that plain Laura was a normal human being who shared in academic life and socialized with others. The other effect is that I see Muslim women not as targets for our scorn or our attempted re-training but as participating human beings. My shared experience of having worn a distinctive head covering and dress has generated cross-cultural empathy. Other proof of an emerging appreciation for Muslim women's clothing appears at the end of Nine Parts of Desire, where even Brooks, after having consistently denigrated Muslim women's clothing, describes her changed response to the chador she wore to do her job:

When I look at that chador I no longer get the little shudder of fear or the gust of outrage that I used to feel when I saw the most extreme forms of Islamic dress. These days my feelings are much more complex. Chadors are linked in my mind to women I've felt close to, in spite of the abyss of belief that divided us. (5)

Facing fewer obstacles than did Brooks, I developed cross-cultural empathy much more easily. Not only "women I've felt close to" but also I myself have worn religiously-prescribed clothing. Living as plain Laura for 31 years prepared me to enter into the experiences of the Other--especially Muslim women in the U. S.

1. Lynette Clemetson and Keith Naughton, "Patriotism vs. Ethnic Pride: An American Dilemma," Newsweek, 24 Sept 2001, p. 69.

2. Geraldine Brooks, Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women (New York: Random House, 1995).

3. Admittedly, I had more freedom than do Muslim women in some countries. In this essay I am describing the similarity between my experience as a conservative Mennonite minority woman and that of a Muslim minority woman in the U. S.

4. Despite my decision not to wear plain clothing and despite my disagreement with doctrinal justifications for this practice, I would probably react similarly to harsh criticism of a plain-clothes Mennonite woman who is a minority in a given situation. Although I do not identify with groups of such Mennonite women, I identify with a single minority figure.

5. Brooks, 234.