One of 4 extant views of the Wadsworth Institute building

December 2002

vol. 57 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents

December 2002

vol. 57 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents

One of 4 extant views of the Wadsworth Institute building

Eight months after the guns of the Civil War had fallen silent, John Oberholtzer, president of the General Conference of Mennonites, was still praising the goodness of God, even though the slaughter had been great.

"For years to come," said he, "people will be talking about the thousands of widows and orphans, the monstrous sacrifice and ruin, the sinfulness—in many cases and places—for so many people.

"We will long remember the frightful decline of a corrupt people and especially the loathing and the lawbreaking, the illegal rage against lawful rulers!"(1)

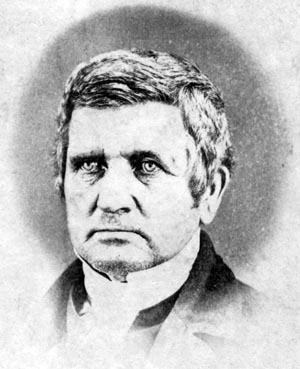

"Early this morning, the ringing bell proclaimed the

solemn celebration of

our school," said John H.

Oberholtzer, leading minister of the Swamp

congregation, Milford Square, Pennsylvania, and

president of the General

Conference Mennonite

Church. "Come now, let us draw near to Zion to see

the

glory of what God has done." (Recently discovered

photograph found in a

family album and loaned to

Maynard Shelly by Verna Sell Willauer.)

Now at the end of 1865, John was in his print shop in Milford Square, Pennsylvania, writing not just to the people of Swamp and other churches in the eastern part of his home state, but to readers in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and even in Canada. In spite of the horrors of the past five years, God, he believed, could make 1866 the best year ever.

With the coming of peace, John, his church in Swamp, and the leaders of the East Pennsylvania Conference could now work to open the school that General Conference folk had been praying for since 1860. They had wanted to send workers out into the world to preach the good news of Jesus Christ. But to do that, they had to build a school, find teachers, and bring students into the class rooms. Only after these folks had been trained could the mission begin.

Daniel Hege, Summerfield, Illinois, in the year before

his death from

typhoid fever, went from church to

church and home to home in Ontario,

Pennsylvania,

Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa, collecting pledges

of

support for the building of the school.

In spite of the war, Mennonites had been at work. Daniel Hege, Summerfield, Illinois, visited churches and families in the United States and Canada and raised $5,739 before his untimely death from typhoid fever at the end of 1862.

This response to the appeal for funds to build a school, while not enough to cover all needs for a new school, was good enough for a start. Never before had Mennonites worked together on a project of this size. Churches with their unpaid ministers had little practice in raising funds. But times were changing. Hege's trip through settlements from Ontario and Pennsylvania to Illinois and Iowa began a new age for these Mennonites. More and more people caught the vision of workers going overseas and preaching Christ.

Excitement for the new school was high when the East Pennsylvania conference met at West Swamp, near Milford Square, in May 1863. "It was the overwhelming opinion of the council that the church may only hope for results and blessing," said secretary Henry O. Stauffer, "when the teaching of Menno Simons as a foundation for instruction is set upon a solid footing."

Ministers and deacons in the Pennsylvania conference asked that the coming General Conference set for October in Illinois begin "the establishment of a school with prayerful forethought."(2)

Building plans for the new school were made at that third General Conference of the Mennonites of North America in Summerfield, Illinois, in 1863. John Oberholtzer was in the chair as presiding officer in that meetinghouse not far from St. Louis. Now was the time to say what they wanted this Mennonite school to be and to do. They wrote 27 articles, using over 1,000 words.

"This we feel most deeply: let's make our witness plain. Hear the call of friends near and far. Great is their need for a real good school. It is our highest duty to respond with all the talent and wealth that God has given us."(3)

So said they at the start of the three-page paper called "Rules for the Christian Educational Institute of the Mennonite Conference." It was a long name which would soon be shortened in everyday use.

Levi O. Schimmel, another Swamp church minister,

would serve the school as

its steward from July 1869

to March 1872.

The rules were written by a group of six, including three from Pennsylvania: John H. Oberholtzer, Levi O. Schimmel, and Ephraim Hunsberger. John and Levi were ministers from the Swamp church in Bucks County. Ephraim, now living in Ohio, was a native of Berks County and had been ordained a bishop by John in 1852, 11 years earlier. A fourth member of the committee, Daniel Hoch, was part of a Deep Run family in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, who had moved to Ontario in the early 1800s. In 1851, on his second trip to Ontario, John had ordained Daniel to be a bishop.

This charter of the first Mennonite school in the new world was signed not only by the 16 delegates (7 elders, 4 ministers, and 5 laymen) but also by 44 others whom the minutes called "advisory members," mostly folk from the Summerfield congregation. John Oberholtzer and Levi O. Schimmel signed for the Swamp church, as did John G. Stauffer, hard-working typesetter in the Milford Square print shop.

Among the other ministers signing the constitution was Eusebius Hershey, a traveling evangelist for the Evangelical Mennonites of Pennsylvania. David Gehman, that group's secretary, had been invited to the Summerfield meeting, probably by Oberholtzer. But on October 1, he told the meeting of his group at Haycock that family concerns would keep him from making the trip.(4) Hershey may have asked to go in Gehman's place, though his interests as a traveling evangelist may also have drawn him to the Illinois gathering.

When the working plan for the new school was approved at Summerfield, the next big question was where? There were 38 votes to be cast. Two went to Pennsylvania, two to "the west," and 34 to Ohio.(5) Three persons from Ohio were named as a building committee. Ephraim Hunsberger, who had lived in Wadsworth for 10 years, was to be one of the builders.

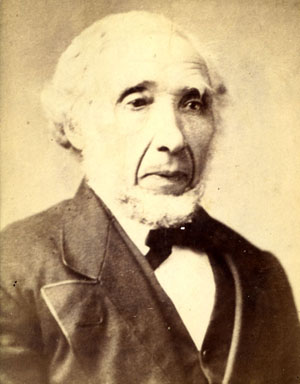

Ephraim Hunsberger (with his wife Elizabeth

Overholt) came from Bally,

Pennsylvania, in 1852,

to build a congregation in Wadsworth.

Three other persons, including John Oberholtzer, were picked to look for teachers and to install these teachers in their work.

Within three months of the Summerfield meeting, the members of the building committee were on the job. They met in Wadsworth for five days in January 1864, and appointed Christian Hunsberger to be their treasurer and paymaster.(6) The executive committee, of which John Oberholtzer was a member, felt that progress on the building was going well and they thought it would be ready for use by the spring of 1865.(7)

Daniel Krehbiel, Cleveland, Ohio, was active in the

design and building of

the Wadsworth Seminary.

Members of the building committee weren't that sure. They had just heard that the man they wanted to be their chief carpenter was being drafted into the army. So said Daniel Krehbiel from Cleveland, Oberholtzer's friend for many years, and a member of the building committee and likely its chairman.(8) Also, they had had no luck finding a bricklayer. But to get started, they excavated for a basement and laid the foundation.

Krehbiel said the school building would have three stories and a basement, be 65 feet long and 38 feet deep. The height of the basement would be 8 feet, the first 3½ feet being below grade. Half of the basement would be used for a cellar, the other half for kitchen and dining room. The first story would be 14 feet high; second story, 15 feet. The building would face south with the main entrance 10 feet wide. An entrance 5 feet wide would open up in the east side. On either side of this doorway would be two rooms for faculty living quarters. The west half of the first floor would be used for two classrooms.

A large open room on the west side of the second floor was to serve as a chapel or lecture hall. The east half of this upper floor would be used for four or more student rooms.

On each side of the main entrance, a masonry wall would rise, starting from the basement. From the first floor to the second story, the bricks would be 12 inches wide with the upper walls made of wood. Plans called for cellar walls two feet thick, faced with 18 inch bricks. At the top of the building would be six Dachstühle (roof trusses) to secure the roof.(9)

In the spring of 1865, work on the school building got under way. Aaron Kent, from Pennsylvania, was the boss workman. The lot was 16 acres. A writer for the local newspaper saw promise of growth for the town. "With the college in the west and the railroad station in the south," he said, "we may reasonably expect that Wadsworth will grow rapidly and become a place of considerable importance."(10)

Yet in May 1865, work on the building had almost come to a halt. Money that had been promised when Daniel Hege had visited the congregations in 1862 had to be collected. Now was the time for Mennonites everywhere to make good on their pledges.

"It is one of the holiest duties of the true Christian," said Oberholtzer in an editorial in the Volksblatt called "The Money," to "support the gospel with all gifts and resources possible in order that the work of the gospel can be spread abroad and the kingdom of God be built up."(11)

Such was the vision of John Oberholtzer and all the leaders of the General Conference Mennonite Church at the beginning of 1865 while the Civil War was still raging. But the unfinished school building at Wadsworth, Ohio, wasn't far from his mind. It had been a hard winter, yet John was hopeful.

"If nothing gets in our way, " he said early in the spring of 1865, "then during the coming summer the building of our school can go forward speedily."(12)

Second of 4 extant views of the Wadsworth Institute building

But a closer look at the building site was not so rosy. The building committee met in Wadsworth at mid-May 1866. It had been a wet winter and it had taken a long time for the ground and stacks of building material to dry out. Yet the brick work was far enough along so that the carpenters could begin their work.

But the committee had a problem—a big one. Ephraim Hunsberger, minister of the local church, had been asked to oversee the building and be on hand to answer questions whenever help was needed. But Ephraim was often busy with his church work or was away making pastoral calls when he was wanted. This local minister, some onlookers might have been saying, really wasn't too eager to be a builder.

"Now, Brother Oberholtzer seems to have a strong will and knows what needs to be done," said the committee. "We want him to come to Wadsworth for at least a month this summer."(13)

John did travel to Wadsworth in May and met with the committee in charge of the building. Words of encouragement written into the minutes may have been spoken by him. "This is a special building to be dedicated to the Lord. It must be long-lasting, for it must serve more than just one generation. Yet we must avoid unnecessary costs. Coming generations may see our work as simple, yet they should see it as something worthy of respect and in good taste."

The committee wanted to be done with its work by the end of 1865 The building was under roof on 16 November. "The windows are in and also the doors. The floors have been laid and the stairs have been built." Then work ceased until spring. "The building," said the committee, "is without grandeur or splendor but such is the nature of the first building to be the home of a Mennonite college in North America."(14)

In the Volksblatt, for 15 June 1866, appeared this note: "J. H. Oberholtzer's postal address will once again be Wadsworth, Medina Co., Ohio, until further notice in Volksblatt."

As it happened, he would be in Wadsworth not only until the school building was finished but until it was dedicated and even later—after the session of the General Conference which met every three years. It would be his longest time away from the Swamp churches and from the Mennonite Printing Union's office in Milford Square. With A. B. Shelly as a second minister in Swamp and as a helper in the print shop, his work in Milford township could go on. John had spent, it seems, a month in Wadsworth the summer before.

As John left Milford Square on Tuesday, 12 June, he was carrying a check of $622.61 from John B. Shelly, Pennsylvania treasurer for the Wadsworth building fund. The builders in Wadsworth would be waiting for the money. Since December, $2,300 had been paid out. New materials had been bought and more money was needed.(15)

When John got to Wadsworth, he gave special attention to the roof of the building. He found it had not been done right. After spending a number of days on the top of the three-story building, he had time to think about what would happen when teachers and students would come together inside this building.

But even before that, the building had to be dedicated to God so the work of being a school could begin.

Dates had to be set for the rites of blessing for the building and the teaching and learning to be done inside its walls. "If nothing unforseen gets in the way, our school building will be nearly finished by October 1866."

They invited the "entire Mennonite community." The new building would be "given over to the Lord" on Saturday and Sunday, 13-14 October. The invitation was addressed to "all Mennonites in the States and in Canada" as well as to "other friends of Christian education."(16)

This festival would be followed by the five-day meeting of the General Conference of the Mennonites of North America. It would begin on Monday morning, 15 October. So John had to plan these two special meetings during his summer in Ohio. That meant he had traveling to do.

Off he went to Iowa to meet with J. C. Krehbiel, West Point, and Christian Schowalter, Franklin Center, on 8 August. They had been hoping to coax the European Mennonite churches to send one or two teachers for the Wadsworth school. Letters had been written and pleas made in the Volksblatt. European Mennonites, who hadn't had to spend more than a century clearing the land and building new homes and churches on a new continent, had been able to go to colleges and universities. But in spite of many pleas, no one from Europe came forward.

So John and the two Iowa ministers on the special committee said, "for the present time, we can no longer look to Europe for teachers. We believe that there are men in America who will understand our school." So they sent out a plea to the churches for persons who could be teachers in their school. They even looked for people who might volunteer.(17)

By this time, many people all over the Mennonite community, not just in Swamp, but in Iowa, Illinois, and Canada were talking about Wadsworth. What would happen once this school in Ohio got started? Some people saw it as "a preacher-machine" turning students into ministers.

An article on the same page as the report about finding teachers said, "Its purpose is not to make preachers but to give young men a religious training so they will be better able to be school teachers, Sunday school teachers—or do other work." No one should see the school as a "preacher-institute" turning all its students into ministers. If congregations would want to call one of these students to serve as a minister, they could, but they should consider other choices and decide who could best serve a congregation.(18)

Although no teachers had been named for the new school, courses of study were being announced—21 subjects in all. At the top of the list were Bible Knowledge, Christian Education, Church History, German, and English. Other classes included Penmanship, Mental Arithmetic, Geometry, Algebra, Geography, Natural History, Philosophy, Public School Instruction and Discipline, Music and Singing, and Drawing.(19)

John Oberholtzer didn't spend all his time during this summer away from Milford Square in looking over the shoulders of the carpenters and plasterers working on the new school building. He took off to do what he seemed to enjoy most—traveling, visiting friends old and new, and seeing new things. Of course, he visited Daniel Krehbiel in Cleveland as he had done on earlier visits to Ohio. From Cleveland, he took a side trip to Oberlin College, as far southwest of Cleveland as Wadsworth was south.

Oberlin had been founded in 1833, growing out of the revivals of Charles G. Finney, who was a professor of the school for its first 42 years and was just completing his eleventh year as president when John came to visit the campus on 24 July 1866. The school was named in honor of Jean Frederic Oberlin (1740-1826), a pastor noted for improving farming, industry, education, and morals in his rural pastorate in Steinthal, Alsace (in the borderland between France and Germany).

Though young, Oberlin was already a leader among schools in the United States. It admitted women from its very beginning. In 1841, it became the first school in the nation to award a bachelor's degree to a woman. In 1835, soon after its founding, it began to accept students of other races.

John's guide on the Oberlin campus was 80-year old Father Keep, a founder of the school, whom he called "a hoary, old man." Oberholtzer had come to learn what a successful school needed in design and rules and how it ought to be put together. He became convinced by what he saw and heard that "a wise person without proper training is only a half person."(20)

Just two weeks before the Wadsworth school building was to be dedicated, John took the train to Cincinnati to shop for a bell for the cupola. It did not need to be paid for out of the school's overdrawn building fund. The people of Wadsworth town had collected money for this adornment for the tallest building in their village. John found an 800 pound bell in the river city and had it loaded onto the train back to Wadsworth.(21)

In his travel report, Oberholtzer wrote six lines about buying the school's bell, but 27 lines about how sick he became on the trip back to Wadsworth. An hour after the train left Cincinnati, he had a severe attack of "cholora morbus," a disease which was then raging in the city he had just left. He felt so much pain that he wanted to leap off the train. But here he was, 700 miles from home in a place where he knew no one. He prayed, throwing himself on the mercy of God. Then he remembered the medicine he always carried, an elixir that had saved him from severe illness three times in the past. Now, for the fourth time, he took a dose. Within a short time he felt better. He had no choice but to share the news of this magic potion: "spiritus of lavender with an opium pill." This, he said, was available in any drug store. "Buy it," he said, "when you don't need it, so you will have it when you do need it."(22)

Chimes from the bell John Oberholtzer brought to Wadsworth sounded a new note of grace through the throng of people who came from near and far to Wadsworth on Saturday, 13 October 1866. The bell sounded out the coming of a new thing. New—and not just to a town in north central Ohio. This new creature spoke out to villages and farms in Ontario, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. For the first time in America, Mennonites had joined their hands and hearts to honor and give glory to their God and Christ. In building the school, they had already engaged the world. And the gospel was taking hold of them.

More than one visitor to the celebration would comment on the bell that had been mounted just three days before the opening service.(23)

Abraham J. Moser, school teacher from Ohio's Sonnenberg community, got up early on that Saturday morning of October to trudge several hours to see the new school building. He wanted to learn whether this school "might serve a good purpose."(24) Moser came, stayed, and became convinced. (He would later become a student at Wadsworth.) His long report, over two pages in an 8-page newspaper, spoke with favor about what he saw and heard.

Christian Krehbiel, Summerfield, Illinois, pointed to

the promise, "Whatever

you ask in prayer...it will be

yours."

The new building charmed Christian Krehbiel, Summerfield, Illinois, from the moment he saw it in the early morning light. He found it "stately, yet without pomp, a treat for the eyes." He was charmed by the freshly-graveled path leading visitors to the double-doored front entrance, 10 feet wide. He climbed the wide inner stairway to the second-floor classrooms and assembly hall with room for 300. On up another stairway, he found the student rooms on the third floor. Then, at last, he made his way to the roof and the tower housing the "melodious bell" that so charmed visitors hearing it for the first time.(25)

The school, one-half mile from the center of the village of Wadsworth, stood at the center of the township, the north-south line passing through the middle of the building, which faced south toward the railroad station. From top to bottom, it was 64 feet high, including the 26-foot observatory and belfry. The building was 65 feet wide and 38 feet deep.(26)

Third of 4 extant views of the Wadsworth Institute building. This is nearly identical to the second view above, but the positions of the people are slightly different.

At ten in the morning of 13 October, the celebration of the new school began. An assembly of visitors and villagers waited in front of the home of Pastor Ephraim Hunsberger and Elizabeth Overholt that faced the new building 200 paces across the road. Daniel Krehbiel, chairman of the Wadsworth Institute board, led the assembly of several hundred people up the path to the entrance of the school. Standing on one of the six front steps, Krehbiel gave the key to the door to John Oberholtzer, president of the Mennonite General Conference. Deeply moved by the meaning of the moment, John spoke to congregation in the school yard.

"Welcome to all of you. Come now, let us draw near to Zion, to see the glory of what God has done."

He took the key, unlocked the door. Above them in the belfry, the new bell rang out a welcome that lifted the congregation up the front steps, through the double doors and up to the second floor assembly room.(27)

A choir from the Brethren church in Ashland, a town about 30 miles southwest of Wadsworth, began the day's celebration with song. (Twelve years later, the Brethren church would build its own college in Ashland.) Choirs from Wadsworth and Hayesville also sang during the two-day festival.(28)

Christian Krehbiel, 32, Summerfield, Illinois, had the honor of being the first of a series of preachers and orators, whose words with hymns and many prayers would mark the two-day celebration. Young and energetic, with a thick black beard, Krehbiel impressed his hearers with his knowledge and forceful delivery. Using a theme from Mark 11:22-24, he urged his hearers, "Have faith in God . . . whatever you ask for in prayer . . . it will be yours." His examples were John Hus, burned at the stake in 1415 in Europe for his efforts to reform the church; Martin Luther; and Menno Simons.(29)

Krehbiel's sermon touched Abraham Moser. "It made a powerful impression on me," he said. "Never before had I heard such a wonderful sermon."

Samuel Clemmer, 45, Clayton, Pennsylvania, preached next. His sermon was taken from Luke 14:17: "Come; for everything is ready now." It was the last sermon for the morning of the first day.

Now, before the school's classrooms, chapel, student rooms, and teachers' quarters were formally dedicated, the kitchen and dining room, taking up half of the basement would be put to the test. Tables newly-built were groaning under the food brought in by church members and townsfolk. People also gathered around tables set up in two of the school's large rooms.

Oberholtzer praised the array of bread, butter, cheese, apples and the crowning dessert known in German as pasteten but cheered by him as PIES! Saturday's noon meal which served about 400 was only prelude to Sunday's noon serving which came to nearly a thousand. Yet so much food had poured in from the town and countryside for the two-day festival that the General Conference meeting that followed had food for three of its five noon meals. John likened it to the miracle of the loaves and fishes.(30)

Andrew B. Shelly, Swamp church's newest pastor,

came rejoicing. "Before this

day, we had no school,

but now we do."

Andrew B. Shelly, 34, Swamp's newest preacher, took his turn in the second session on Saturday to say what this event meant to him. He saw the school as an open door for the Mennonite church to preach the gospel. He used Martha's words to Mary, "The Teacher is here and is calling for you" (John 11:28). God has entrusted us with wealth. "What have we done until now? What have we done before this for our youth? Have we sent them out as missionaries?

"Before this day, we had no school. But now we do!"(31)

John C. Krehbiel, West Point, Iowa (with his wife,

Katharina Raeber), had

called the meeting in 1860

that led to the founding of the General

Conference

Mennonite Church. "For many years, we knew

nothing about each

other, but now we do."

"This is our house," said John C. Krehbiel, 55, West Point, Iowa, who came to the pulpit next. He had been chairman of the group in Iowa calling in 1859 for a meeting of all Mennonites in America. His call got the General Conference going with a meeting in his home town in 1860 to which John Oberholtzer came from distant eastern Pennsylvania. "For many years," Krehbiel now said in Wadsworth, "we knew nothing about each other."

Reflecting the loneliness of pioneer life on the prairie, he said, "We couldn't imagine other groups existed."

But now they not only knew each other but were working together. Said he, "This is our house." Wadsworth Institute, indeed, was cause for much gladness for many of the Mennonites of 1866.

The next day, Sunday, 14 October, was Wadsworth Institute's dedication day. "Early this morning," said John Oberholtzer, "the ringing bell proclaimed the solemn celebration for our school."

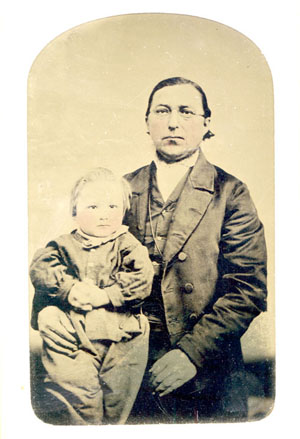

Christian Schowalter (with his son), Franklin Center,

Iowa, would become the

school's first principal.

(from a tintype)

Using words from Isaiah 63:16, "You, O Lord, are our father, our Redeemer from of old is your name," Christian Schowalter, 37, Franklin Center, Iowa, set the mood for the day. The hall was packed with attentive listeners who hung on every word.(32)

To Oberholtzer, 57, as General Conference president, was given the task to dedicate the school. He started with a verse from the New Testament: "Out of the believer's heart shall flow rivers of living water," (John 7:38). "Let this verse be the motto for this place. This school," he said, "will be a fountain of blessings through our faith in Jesus Christ."

He asked the congregation crowded in the upstairs chapel to stand as he fell on his knees. He prayed earnestly to the Almighty and Eternal God who through Christ the Son had freed believers from the bonds of death. He thanked the ever-loving Father for divine goodness and truth, for blessings overflowing on this house his children had built.

"Fill it with the Holy Spirit," he prayed. "Protect this place from fire, storm, and all misfortune. Never withdraw your protecting hand from it. Let this school stand as a reminder of your everlasting grace. May nothing be taught or learned here to hinder the spread of your rule and the glory of your holy name. May many true witnesses of truth go forth to tend the people of your flock feeding on the green pasture of the gospel. Lead them to the springs of water that will quench every thirst.

"Bless all who supported the building of this house with their hands and their gifts, even those who donated no more than a mite to the building of the Wadsworth Institute. Repay them twofold and bless them with present and eternal good fortune, for the kingdom and power belong to you of the gentle hand who is ready to bless. Visit us today in our 'huts of dust.'"(33)

It was high noon. The large assembly took time out for its noon meal served in other rooms of the building. Hundreds, perhaps a thousand, took part in a humble but generous feast.

The afternoon service was brief, limited to two sermons, though the crowd was great. Jonas Y. Schultz, a Schwenkfelder from Pennsylvania and a supporter of William Gehman's Evangelical Mennonites, appeared behind the pulpit of the General Conference Mennonite Church's new school. Oberholtzer noted the text chosen by Schultz from 1 Kings 8:29, where Solomon speaks with God about the temple built in Jerusalem. God said "My name shall be there," a promise that God would heed the prayers believers directed toward the temple.(34)

Abraham Moser remembered that Levi Schimmel, Swamp pastor, gave a short address. After that, Moser left Wadsworth to walk back to Sonnenberg. But Oberholtzer notes in his report that on Sunday evening a man named C. H. Reuter, gave an address in English, from 2 Peter 3:18: "But grow in the grace and knowledge of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ."(35)

Now after the lavish ceremonies of these two days in October, in which John Oberholtzer and the General Conference had celebrated their ownership of a school building, joy was already mixed with regret. Wadsworth Institute was a school not yet up and running. It had no students—because it had no principal, no teachers. Compared to the struggles of raising funds and erecting a building, finding the right person to lead the school was far more difficult to locate.

But the building would not stand empty for long. Pastor J. G. Encell, with experience as a teacher, proposed opening a "select school" beginning 12 November for 14 weeks. Cost would be $4.50 per student, 50 cents more for those taking Latin.(36)

After two days celebrating the high hopes of opening the first church-supported Mennonite school in North America, 32 delegates to the fourth three-yearly General Conference began meeting in the college chapel on Monday, 15 October.(37) It would be a five-day meeting that would not adjourn until late Friday night.

A major move at this conference was forming a "Central Mission Society for the united Mennonite congregations of America." It was much like the mission society put together at Swamp. That local society worked on getting people to learn about missions and to raise money for mission programs. The General Conference society would set its sights on doing mission work. Java, where European Mennonites were already at work, was one place listed. All three officers elected to this mission society were from Wadsworth.(38)

Fourth of 4 extant views of the Wadsworth Institute building

Also talked about at this meeting was John Oberholtzer's plan to move the Milford Square newspaper printed in Pennsylvania since 1852 to Wadsworth, Ohio. There, he said, students and faculty could do the writing and printing work. But with the opening of the school postponed, no action could be taken.(39)

But even after the conference, folks in the town of Wadsworth were keeping the idea alive. The local newspaper's editor looked forward to the Volksblatt's being relocated in his town. The Volksblatt "and the Enterprise office will probably be consolidated," he said, "but each paper will retain its distinctive features."(40)

The Wadsworth conference was running late on its fifth and last day. It was Friday and the time on 19 October was moving toward midnight. But two more items remained.

The first dealt with John Oberholtzer as conference chairman. "For his many hours and much effort serving the needs of the Conference, we offer him $100 out of the Institute treasury." That was for four months of work during the summer and fall leading up to the dedication of the school.(41)

Still more gratitude was passed on to Anna Brons, a scholar living in Emden, Germany, who had sent 18 sermons from Mennonite preachers in Europe to the Volksblatt for John to publish. She had also sent a picture of Menno Simons to hang in the chapel of the Wadsworth Institute. Of course, the Conference said thanks to Mrs. Brons. But in the letter composed late on the night of the last day, we discover that she had also sent a medal for the school. What was engraved on the medal? That we were not told. But the delegates asked John Haury from Summerfield, Illinois, to fix the medal to the school building "for all time."(42)

Anna Brons, Mennonite writer and scholar, Emden,

Germany, sent a picture of

Menno Simons for the

chapel and a medal to be fixed to the building "for

all

time."

At midnight, the bell, rung during the Wadsworth Institute's dedication, rang out on this seventh day at midnight to mark the end of the fourth General Conference.

Said John, "We fell on our knees at the footstool of God owning that we had prayed as children—what we had done had been done in weakness. We were seeking God's blessing. Pardon us where we might have prayed for something against God's will. Amen."(43)

Anna Kreider Juhnke with the Wadsworth Institute bell on October 26, 2002, shortly before

the bell was moved to Elkhart, Indiana, to the campus of Associated Mennonite Biblical

Seminary. Juhnke is the author of an article, "The Wadsworth School," in the April 1959

issue of Mennonite Life, 66-69.

In October 2002 the First Mennonite Church of Wadsworth, Ohio, celebrated its 150th anniversary. As part of the celebration, Denton Croyle, the congregation's archivist, arranged to transfer the old Wadsworth Institute bell to the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Indiana. The bell had been located at the original Wadsworth Institute site, now Isham public school.

1. "Das neue Jahr, 1866," Christliche Volksblatt (CVB), 1 Jan. 1866, 34.

2. Thirtieth Session, Minutes of the Eastern District Conference, 1847-1874, as translated by Silas M. Grubb.

3. "Ordnung der Christlichen Bildungsanstalt der Mennoniten-Gemeinschaft," Verhandlungen der Allgemeinen Konferenz der Mennoniten von Nord-Amerika—Erste bis elften Sitzung (VAK) [Proceedings of the General Conference of the Mennonites of North America—First to Eleventh Sessions] Berne, IN: n.d., 15

4. "Verhandlungen der Evangel. Mennoniten Conferenz," CVB, 14 Oct. 1863, 22.

5. VAK, 20.

6. "Nachricht von der Bildungsanstalts-Verwaltnungscommitte," CVB, 20 Jan. 1864, 46.

7. "Die Bildungsanstalt," CVB, 1 June 1864, 86.

8. "Bericht der Verwaltungs Komitee" [Report of the Management Committee], CVB, 1 June 1864, 86. The report is only signed in the name of the committee, but it seems likely it was written by Daniel Krehbiel. Other members of the committee were Ephraim Hunsberger, Wadsworth OH, and Michael Lehman, Savannah OH; VAK, 20.

9. Report of the Management Committee, 86.

10. Wadsworth Enterprise, 18 May 1886. See Rachel W. Kreider notes from the Wadsworth Enterprise, folder 7, box 2, III.1.F. Wadsworth Institute records, Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, KS.

11. "Das Geld," CVB, May 1865, 34.

12. Editorial comment, CVB, 1 Mar.1865 [dated in error as Feb.], 26.

13. "Über die Angelegenheit und den Fortgang des Baues unserer Bildungstalt" [About the matter and the progress of the building of our college], CVB, May 1865, 34.

14. "Report from the Administrative Committee About the College Building," CVB, 1 Jan 1866, 34.

15. "Bericht," CVB, 15 June 1866, 78.

16. "Einweihung der Bildungsanstalt," CVB, 15 Sept. 1866, 90.

17. "Teachers for the Educational Institute," CVB, 15 Sept. 1866, 90.

18. "Unsere Anstalt" [Our Institute], CVB, 15 Sept. 1866, 90.

19. "Was in unserer Bildungsanstalt gelehrt werden soll" CVB, 15 Sept. 1866, 90.

20. "Reisebericht von J. H. Oberholzer," CVB, 15 Sept. 1866, 90.

21. "Schluss von J. H. Oberholzers Reisebericht," CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 98. The weight of the bell was published in the Wadsworth Enterprise for 12 Oct. 1866. See Rachel W. Kreider notes from the Wadsworth Enterprise.

22. "Schluss von J. H. Oberholzers Reisebericht," CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 98.

23. Wadsworth Enterprise for 12 Oct. 1866 as cited by Rachel Kreider in "A Mennonite College Through Town Eyes," Mennonite Life, 32:2 (June 1977), 8.

24. A. J. Moser, "Die Einweihung der mennonitschen Bildungs=Anstalt in Wadsworth, Ohio, am 13 und 14 October 1866," Mennonitische Friedensbote, Jan. 1867, 1.

25. [Christian Krehbiel], "Reisebericht" [Travel Report], CVB, 15 Dec. 1866, 102.

26. Wadsworth Observer, 18 May 1866.

27. Oberholtzer's travel report, CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 98.

28. VAK, 26.

29. Moser, 1.

30. Oberholtzer's travel report, 98. In the midst of Oberholtzer's report written in German appears, in caps and in English PIES.

31. Moser, 2.

32. Oberholtzer's travel report, CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 98.

33. Moser, 2,3. Oberholtzer's own summary of his prayer appears in his travel report, CVB, 15 Nov 1866, 99.

34. Oberholtzer, CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 99; Moser, 3.

35. Oberholtzer, 99.

36. CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 99.

37. VAK, 22. Only 18 are listed as delegates with credentials from a congregation. The others (14) are referred to as advisory members, but are not named.

38. VAK, 25.

39. VAK, 24.

40. Wadsworth Enterprise, 25 Jan. 1867, as quoted in Rachel W. Kreider notes from the Wadsworth Enterprise.

41. VAK, 26.

42. VAK, 26.

43. Oberholtzer's travel report, CVB, 15 Nov. 1866, 99.