Rachel Weaver, junior at Goshen College 1929-1930

December 2002

vol. 57 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents

December 2002

vol. 57 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents

On January 12, 1934, when George W. Rightmire, president of Ohio State University, suspended seven conscientious objectors who refused military training, Rachel Weaver Kreider was working on a term paper about "my people, the pacifist Anabaptists." (1) Kreider was a graduate student at OSU, making progress toward a Masters of Arts degree in philosophy. Her Mennonite peace convictions drew her into a public protest movement against the university's repressive militarism. The event marked her coming out as one of the early Mennonite women peace activists.

Rachel Weaver had absorbed peace concerns from her parents. She was eight and nine years old during World War I (1917-18) when her father, Sam Weaver, served as a counselor to Amish and Mennonite draft-age young men in LaGrange County, Indiana. Rachel listened intently and stood wide-eyed as her father notarized papers certifying the convictions and church membership of the worried draftees. She was proud that her father knew so much and was so important that people came to him for help. He had been superintendent of the Shipshewana elementary and secondary schools, but had resigned in 1917, partly for health reasons and perhaps partly because of wartime pressures upon Amish and Mennonite pacifists. This war was serious business. (2)

Rachel's father was also a pastor at the Forks Mennonite Church 1904-16. He had studied at Valparaiso University and had graduated from Goshen College in 1911. A framed copy of his graduation certificate from Goshen hung on the Weavers' living room wall, a sign for Rachel of the importance of higher education. Rachel excelled in elementary and secondary school, and went on to Goshen College herself, graduating in 1931 with a major in Latin. At Goshen she took classes under professors Harold S. Bender (sociology) and Guy F. Hershberger (history), both of whom became prominent Mennonite denominational peace leaders.

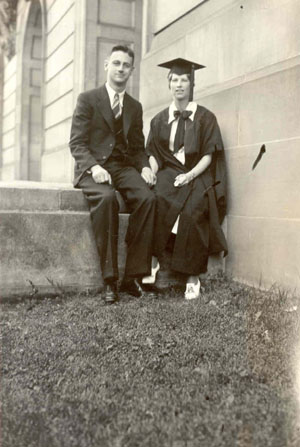

Rachel Weaver, junior at Goshen College 1929-1930

While Rachel Weaver was absorbing peace as a core Mennonite value, she and her family were scarred by the church's conservative adherence to separatist practices that the Weaver family considered unimportant. The church enforced a rigid dress code for women, including, at the Forks Church, a rule requiring strings attached to the regulation bonnet. Rachel's mother, Laura Johns Weaver, took off the strings, and the church held her back from communion. When Sam Weaver resigned from the ministry in 1916, he was discouraged with the church's legalism and its opposition to education. In 1923, when a growing Mennonite cultural crisis led to the closing of Goshen College, Weaver and his family joined a more open and liberal congregation-the Eighth Street Mennonite Church in Goshen.

At Goshen College Rachel met and fell in love with Leonard Kreider, from Wadsworth, Ohio. They delayed marriage because they were poor and the country was in an economic depression. After graduation in 1931, Rachel got a job teaching English and Latin in the small town of Roann, Indiana. Rachel and Leonard were married in the summer of 1933, and began life together in a small attic room near the Ohio State University campus in Columbus. Leonard studied for a PhD in chemistry. Rachel took courses in religion and philosophy. There were about twenty-five Mennonites at OSU.

Leonard and Rachel Weaver Kreider, married June 20, 1933

By the early 1930s, military training had become a bone of contention on university campuses across the nation. The U.S. Congress had encouraged military training in public schools in National Defense Acts of 1916 and 1920. The War Department provided colleges and universities with funds and staff for Reserve Officers' Training Corps. By 1927, eighty-six colleges and universities had mandatory ROTC, and forty-four offered it as an elective. National peace organizations mobilized opposition to the military training. The Fellowship of Reconciliation led the way with a "Committee on Militarism in Education." (3)

Ohio State University instituted compulsory military training, but exempted members of historic peace churches. The exemption reflected the government's policy for conscientious objectors during World War I. In 1931-33 the number of conscientious objectors at Ohio State University began to increase, a reflection of a growing peace movement throughout the country. Dr. Robert Leonard Tucker, a Methodist pastor in the university district, influenced idealistic young men from his denomination to refuse ROTC. Initially the university administration responded to the growing number of conscientious objectors by extending the exemption to students not from historic peace churches. But by the 1933-34 school year, the number of applicants rose to nearly forty. Administrators thought the situation was getting out of hand. The president instituted a new system for evaluation of the conscientious objectors, substituting a four-hour course on "Preparedness" and two hours of physical education for those judged sincere. On January 12, 1934, seven students judged insincere were notified that they had been suspended from the school.

Rachel Kreider was midway through her first year at the university when the seven students were suspended. She became "thoroughly interested" in the controversy. During the following school year she made a point of being "somewhere in the neighborhood when the issue would be raised." (4) She reported that "Military propaganda is exceptionally strong here and there are big fat army men all over the place." A Pacifist Club was established on the same day as the suspension of the CO's, and it published several issues of a newsletter, "The Ohio State University Peace News." Roy Zook, secretary of the Pacifist Club, and Kenneth Burkholder, visited Leonard and Rachel and asked whether she could get help from some Mennonite leaders. Zook doubted that the Ohio Mennonite ministers would support the effort. Mennonite leaders wanted their young people to attend Mennonite schools. Some students attended state universities as a way out of the Mennonite community.

In the fall of 1934, Ohio State University announced that no freshmen or sophomore men would be excused from military drill except for physical reasons. The various peace groups, including members of the National Student League (a communist affiliated organization), attempted to increase their effectiveness by cooperating in an organization called the United Front Committee (UFC). Rachel did not officially join the UFC, but she did show up in October 1934 when the group met with President Rightmire. At that meeting she presented the Mennonite viewpoint. In her words: "I told the president that if our boys are true to the four hundred years of history behind them they will not bear arms and are therefore barred from a state institution, a rather unjust discrimination against a law-abiding tax-paying people like the Mennonites of Ohio." (5) Rachel was slightly embarrassed when the campus newspaper, The Lantern, in reporting the encounter, said that someone had represented the Mennonites. She had spoken as an individual.

Another focus for peace activist witness was the Ohio state legislature. At the initiative of some church leaders in Ohio, a bill was introduced to make ROTC voluntary in state universities. Students wrote letters to church leaders to mobilize support for the bill. Rachel wrote one letter to Dr. Jacob C. Meyer, a Mennonite professor of history at Western Reserve University in Cleveland. She hoped Meyer might use his connection with Newton D. Baker, who had been Secretary of War during World War I, and who was now on the Ohio State University board of trustees. At that point, the peace activists were attempting to get the bill sent to the Schools Committee rather than to the Military Affairs Committee, where it would not get support. Rachel also wrote letters to Ohio Mennonite pastors in Bluffton (Irwin W. Bauman), Wadsworth (Wilmer Shelly), Dalton (Austin R. Keiser), and Canton (Otis Johns). Several of these men responded, but not in time to be helpful in the legislative process.

The bill was sent to the Military Affairs Committee, and Rachel attended the hearing when testimony was presented from both sides. She said it was "a most interesting experience." The main witness for the bill was the Methodist pastor, Dr. Tucker. A Quaker and a student representative from the YMCA. also spoke. But the peace testimony was overwhelmed by the other side. A former State Commander of the American Legion dramatically accused the students of using the issue "to pump people full of communist propaganda." A Legion Post chaplain railed against the "pseudo-conscientious objectors." The vice president of Ohio State University then "in his calm, serene way surely took the starch out of our side." He said the university was doing what the state legislature wanted, what the university faculty had voted for, and what would contribute most to national defense. The bill died in committee. But the process had contributed greatly to Rachel's education in peace activism.

Rachel was distressed that the various groups and individuals protesting the university policy-Pacifist Club, YMCA, Fellowship of Reconciliation, communists, and others, had difficulty cooperating with each other. The attempt to form a United Front Committee failed, in part because the communists were so aggressive that others had trouble working with them. The YMCA decided not to cooperate with the United Front. On November 29, 1934, Rachel wrote a strongly-worded letter to the YMCA leaders, urging them to reconsider their decision. "We never needed union more," she wrote. "I am sure there is a way to rise above our divisions if we will and we will if we mean what we say." (6) Later she admitted that she became "a little wiser in knowing how the Communists work." (7)

Leonard and Rachel Kreider, June 1935

On April 12, 1935, students across the country participated in a "strike" against war organized by religious pacifists and left-wing student groups. Some 150,000 students nationwide were involved. (8) At Ohio State University the communist-dominated National Student League took over the demonstration. Their main speaker attacked both American imperialism and the pacifists. A crowd of students, one third of whom were uniformed ROTC men, showed up. (9) The speech prompted loud boos from the ROTC supporters and embarrassment on the part of the peace groups. Rachel reported, "I never saw so little sense shown, and the whole group of pacifists had to bear the brunt of it."

The peace groups, Communists excluded, managed to organize another demonstration on May 29, 1935, the day before Decoration Day. President Rightmire had dismissed classes for the holiday. Ernest Fremont Tittle, a prominent Methodist pacifist from Chicago, was to address a large outdoor gathering. But it rained hard that day and the meeting was held in University Hall. Rachel was one of five students on the stage but had no role in the program. Later that same day Rachel had her Master's oral examination. Despite tension and exhaustion, she passed the exam.

Today we know about Rachel Kreider's peace activism at Ohio State because her former teacher, Guy F. Hershberger, was collecting information for the archives at Goshen College about Mennonites and peace. He asked her what had happened in Columbus, and she responded with a seven-page single-spaced letter, along with newspaper clippings, correspondence, and other information. In her letter, Rachel got in a dig at Mennonites who put "bonnet-wearing and pacifism . . . on the same level." She asked that Hershberger return most of the materials when he was done with them, but he kept them for the archives. (10)

In Rachel's final year at Ohio State, lack of funds kept her from taking courses toward a Ph.D. degree. While her husband Leonard finished his degree, she worked on a genealogy project to trace both the Weaver and Kreider family lines. By the time Leonard was ready to send his dissertation to the bindery, Rachel also had an impressive manuscript completed. The manuscript began with the term paper on "my people, the pacifist Anabaptists," and concluded with the genealogy. They had both documents bound, representing significant achievements by both husband and wife. Later in her career, Rachel Kreider became a distinguished genealogist and church historian, best known for the magisterial work co-authored with Hugh Gingerich, Amish and Amish Mennonite Genealogies. (11)

Rachel Weaver Kreider, MA Ohio State, June 1935

In the midst of her Ohio State peace activism, Rachel wrote an entry in her personal journal reflecting on her personal style and role:

No matter how much I aim to stay quiet and irresponsible I always get myself into some situation eventually where I'm exceedingly busy and trying to push something through and yet never being an obvious member of anything. The latest thing is this matter of compulsory military training.(12)

Rachel Kreider's self-characterization of 1935 applied to her continuing peace work over the next seven decades. She was usually a mover and shaker in secondary roles, as her role as homemaker and mother of three children allowed. At times she hesitantly accepted committee chairmanships. In North Newton, Kansas (1937-49), she chaired for several years the local chapter of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. (13) In Wadsworth, Ohio, she continued WILPF work, and helped the American Friends Service Committee to start a "pilot project" in community peace organizing that she sustained as secretary over the decades. She served on the Peace Committee of the General Conference Mennonite Church. In Goshen, Indiana (1982- ), she continued a lively interest in world affairs, writing to her representatives in Congress. She attended meetings of the local Seniors for Peace. When President George Bush threatened war against Iraq in the fall of 2002, Rachel Kreider, ninety-three years of age, offered her peace testimony as firmly and passionately as she had at Ohio State University in 1934-35.

1. Rachel W. Kreider, "The Background of Mennonitism in the Reformation." Term paper for History 608 (The Reformation), Ohio State University, March 1934.

2. Rachel W. Kreider interview with the author, October 15, 2002.

3. Charles Chatfield, For Peace and Justice, Pacifism in America 1914-1941. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1971), 152-7.

4. Rachel Kreider letter to Guy F. Hershberger, September 28, 1935. Archives of the Mennonite Church, f. 46, b. 36, Hist. Mss. I-3-5.7.

5. Ibid.

6. Letter from Rachel Kreider to The Y.M.C.A., November 29, 1934.

7. Kreider to Hershberger, September 28, 1935.

8. Charles DeBenedetti, The Peace Reform in American History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), 126. Lawrence S. Wittner, Rebels Against War, The American Peace Movement, 1933-1983 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984), 6. Wittner reported the number of strikers as 60,000.

9. Undated newspaper clipping, "Anti-War Speakers Heckled," probably from The Columbus Dispatch, April 13, 1935. Archives of the Mennonite Church, f. 46, b. 36, Hist. Mss. I-3-5. 7.

10. My thanks to Theron Schlabach who discovered this file in July, 2002, in the course of his research for a biography of Guy F. Hershberger. Schlabach to Juhnke, July 24, 2002.

11. Gordonville, PA: Pequea Publishers, 1986.

12. Rachel Kreider journal entry, February 27, 1935.

13. Kimberly Schmidt, "The North Newton WILPF: Educating for Peace," Mennonite Life, December 1985, 8-13.