The Experience of Farmers

Lora Jost

Artist Statement

The “Experience of Farmers” is an art project that uses pictures and words to explore the experiences of farmers at a difficult time. The project developed out of concerns about the farm crisis and how this crisis is affecting farm families, rural communities, and the broader society. Low commodity prices are squeezing many independent farmers out of farming, and this project explores the joys and struggles of farmers, and what society loses when independent farmers lose their livelihood.

Since July of 1999, I have interviewed and tape-recorded the voices of forty-two farmers, farm family members, and farmer advocates for this project. Quotes transcribed from the interviews are included directly in the artwork, or on text panels beside the artwork. Themes in the project include: experiences of the countryside, the joys of farming, the farm family, the experience of drought, the beauty of rural Kansas, the perseverance of farmers, discrimination against black farmers, the erasure of independent business and agriculture, and the effects of corporate mergers and multinational corporations on rural communities.

In my artwork I enjoy creating rich surface textures, careful compositions, and fanciful images to capture moments in the stories -- from mundane to whimsical to socially urgent. To make the black and white drawings I use an art material called clay board. This material includes a thin layer of white clay covered with black ink, affixed to a Masonite surface. I scratch off the ink with a sharp tool to create white lines, cross-hatching, and textures. The collages I make include a combination of materials such as photos, magazine pictures, embroidery thread, cloth, and paint.

Collaboration with farmers and organizations was a fundamental part of “The Experience of Farmers.” I collaborated with eight Lutheran churches from Kansas - from Belleville, Beloit, Concordia, Courtland, Glasco, Mankato, Norway, and Scandia. The churches, through the City of Glasco, provided matching funds for a Grassroots Grant from the Kansas Arts Commission to fund interviews with farmers from each church. I believe the churches were interested in this project as an outreach project offering farmers a chance to talk about their concerns in a way that would reach an audience beyond their local communities. I was also granted a month-long residency at the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center in Minnesota to work on the project. Assistance in locating other farmers for interviews was provided through Jerry Jost of the Kansas Rural Center, friends and family. Farmers from the Newton, Kansas, area and Lawrence, Kansas, area were also interviewed for this project, as well as farmers from Nebraska and Minnesota.

I received my MFA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1992, and my BA from Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas, in 1988. I have a studio in Lawrence, Kansas and work as an artist, illustrator, muralist, community arts organizer, and educator. I grew up in North Newton, Kansas.

"The Experience of Farmers" has been exhibited in libraries, coffee shops, peace centers, galleries, conferences, the state capitol, and other spaces in the Kansas communities of Topeka, Lawrence, Newton, Concordia, and Kansas City. Future exhibits are scheduled for Kansas City, Kansas, and Winnipeg, Manitoba. If you are interested in this exhibit being shown in your community, or have comments about this project, please email Lora Jost at lorajost@hotmail.com, or call Lora at 785-832-9860.

Artist Lora Jost (middle) with Joan Nothern and Richard Theis

who helped bring the exhibit "The Experience of Farmers" to Condordia, Kansas.

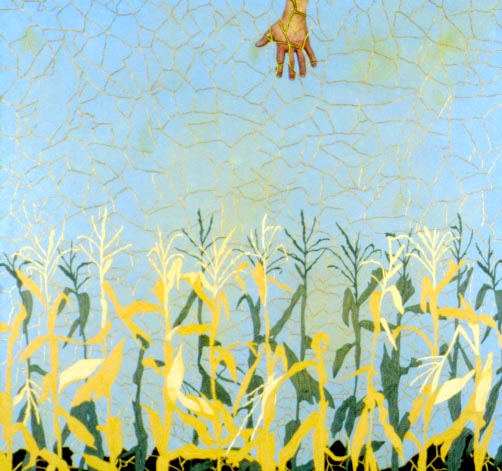

“Drought”

mixed-media (acrylic paint, magazine photo)

It is really a very critical time for a farmer if he is not irrigating, and looking for rain, it’s almost -- you get sort of a tight feeling in the pit of your stomach, whether -- will there be a crop or won’t there be a crop.

And everything depends on that.

--Robert Epp, Farmer, Henderson, NE 8/3/99

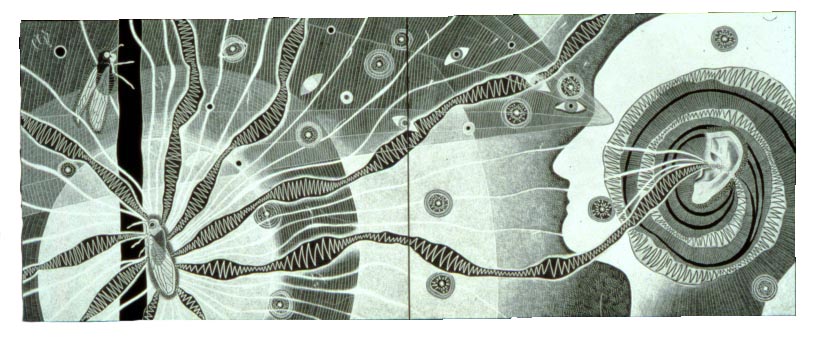

“The Locust”

clayboard

We were in, it’s been fourteen years ago, we had, our second son had cancer. So I spent five months down in Kansas City in the Med Center. And while we were there, there were these grandmothers, older women -- (Laurie)

And men -- (Bill)

And men that would come in every day and give the parents a break. And they’d rock their babies or read them a story, or whatever -- I mean they did this every day so that the parents could get away. And this lady that came to our room, she’d lived in Kansas City her whole life, and she was an African American lady. And I had gone home on the weekend and so she came in Monday. And I was telling her how -- it’s stressful being there anyway -- and then to come home and leave your child -- in one way it was stressful but in another I had to get away or I’d go crazy. And I was telling her, ya know, about the locust -- (Laurie)

Sitting out in the evening -- (Bill)

Listening to the locust because it was summertime -- it was May through September when I was down there. And I was telling her, you know, how lovely the stars -- there’s just millions of ‘em -- cause where we are -- it’s just dark so you can see just billions of stars. And she -- she said to me, she said, well what does a locust sound like? In her whole life, in her whole life, she didn’t know what a locust sounded like -- she’d never heard one. (Laurie)

But if you listen -- (Bill)

And I thought, you know, you -- what you’ve missed. (Laurie)

When we were walking to the Ronald McDonald House, back and forth in the evening, if we listened, you could hear ‘em in amongst all the traffic noise -- (Bill)

Because we knew what we were listening for. But she didn’t know that that was a locust. (Laurie)

But you’re out where it’s quiet and they just fill the air. And down there it was just more -- (Bill)

Well there’s traffic noise and all that with it, and so you don’t even hear it. You know, you just blend all those sounds together unless you know what you’re listening for. Anyways, she didn’t know, and I just thought, how sad, how sad not to know what a locust sounds like all by itself. But she’d never left the city. (Laurie)

--Bill and Laurie Tobald, Farmers, Glasco, KS 12/15/99

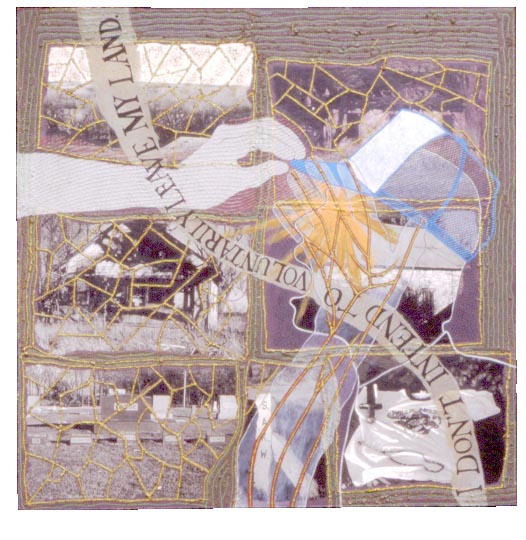

“I do not Intend to Voluntarily Leave my Land”

mixed-media (acrylic paint, dirt, photos, collage)

Jake spent four hours with me, taking me to important sites in and around Robinson, Kansas. As we rode together in Jake’s truck, he told me about his family who had farmed in that area for five generations. Jake has taken exceptional risks to hang on to his land and his heritage. I don’t think Jake would mind if I told you that he expresses his emotions freely, and the orange flash in this picture represents the burst of tears that came when Jake was telling me about a very tragic incident that is part of his story.

The ghostly hand in this picture reaching for the farmer’s hat represents dark forces at work, trying to strip Jake of his land and livelihood. The photo images in this collage were from snapshots that I took which represent aspects of Jake’s land, livelihood, and heritage. There’s the abandoned house where Jake lived as a kid. There’s a stone barn like the one his ancestors had owned. There are also treasured objects that Jake owns -- a sword from the Civil War, an old rosary, a Willie Nelson farm-aid t-shirt.

Jake is a rural activist and in the 1970s helped organize against the building of a dam which would have flooded a lot of farmland in his area.

He also fought against a swine confinement facility that polluted the water and made his children sick. And in the 1980s he fought foreclosure of his farm, largely through the legal system.

--Lora

Quote (within artwork) by Jake Geiger, Farmer, Robinson, KS 11/28/99:

I do not intend to voluntarily leave my land.

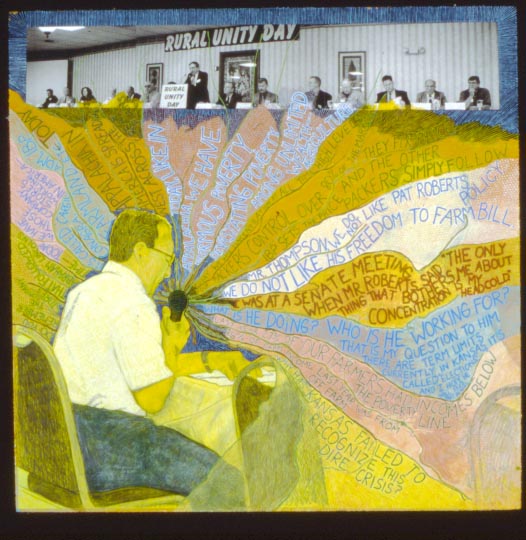

“Testifying at Rural Unity Day”

mixed-media (acrylic paint, embroidery thread, photos)

Quote (within artwork) taken from excerpts of Mike Callicrate’s testimony at Rural Unity Day, 1999:

Do you remember the company stores that followed Abraham Lincoln’s time?... Today we have those company stores working in America -- it’s called Cargil, Conagra, ADM, IBP, Farmland, etc. Today Appalachia in America is spreading west across the great plains. Today, like in Appalachia, we have enormous poverty, devastating poverty among unlimited wealth -- agriculture... Last year 27% of our farmers had incomes below the poverty line, the largest sector of poverty in the United States. 86% of farm income last year was from off farm. Why has Kansas, so far, failed to recognize this dire crisis?... Today we have concentration at all time high levels. Four packers control over 80% of the beef market. They fix price - IBP sets the price, and the other packers simply follow. Mr. Thompson, we do not like Pat Roberts' policy. We do not like his Freedom to Farm Bill. I was at a Senate Hearing when Mr. Roberts said, “The only thing that bothers me about concentration is my head cold.” What is he doing? Who is he working for?

That is my question to him. There are term limits currently in Kansas, it’s called elections, and I hope he will keep that in mind.

“Dirt in His Veins”

mixed-media (acrylic paint, dirt)

Do you think there’s ever a time when things -- should farmers just hang on til the bitter end, or is there a time to get out? (Lora)

And do what... And do what? That’s their whole life -- that’s -- that’s -- that is -- that’s their person. (Laurie)

There depends, how do you put it? If they don’t have blood in their veins, if they’ve got dirt in their veins, well they’ll hang on til the end. If they’ve, if they got a little bit of blood and some brains,well, and they see the handwriting coming on the wall, well, they’ll get out. (Bill)

--Bill and Laurie Tobald, Farmers, Glasco, KS 12/15/99

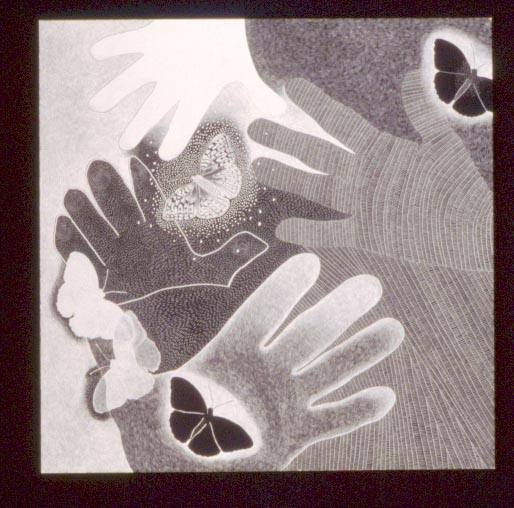

“Catching Butterflies”

clay board

If I was going to have a visual representation of my farm, it would probably be -- I would hope it would be something like Barb and I and my kids walking through a pasture, you know, or stooping down and looking at a bug or an animal, or looking at the wildflowers in the pasture or something. We try to be aware of what’s growing here, and how we’re impacting the land.

--Joe Smucker, Farmer, Newton, KS 9/19/99

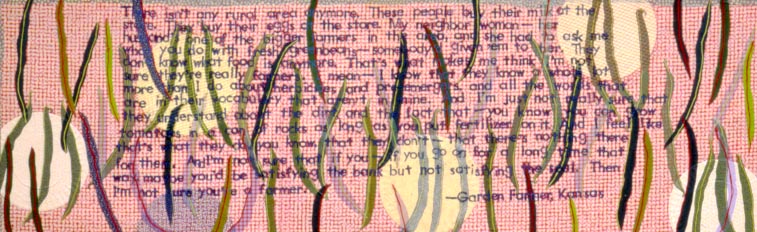

“Green-beans”

mixed-media (cloth, embroidery thread, paper plates, acrylic paint)

Quote (within artwork) by a Kansas Garden Farmer, 1999:

There isn’t any rural area anymore. These people buy their milk at the store. They buy their eggs at the store. My neighbor woman -- her husband’s one of the bigger farmers in the area, and she had to ask me what you do with fresh green beans -- somebody’d given them to her. They don’t know what food is anymore. That’s what makes me think I’m not sure they’re really farmers. I mean -- I know that they know a whole lot more than I do about herbicides and pre-emergers, and all the words that are in their vocabulary that aren’t in mine. And I’m just not really sure that they understand about the dirt, and the fact that -- you know you can grow tomatoes in a can of rocks as long as you put fertilizer on it. And I feel like that’s what they do, you know, that they don’t -- that there’s nothing there for them. And I’m not sure that if you go on for a long time that way, maybe you’d be satisfying the bank but not satisfying the soul. Then I’m not sure you’re a farmer.

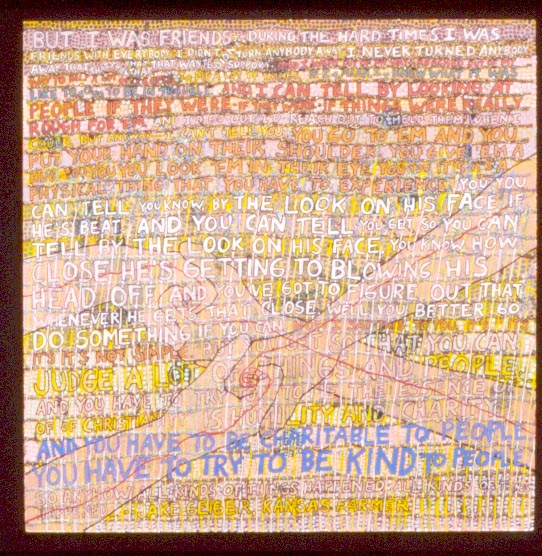

“During the Hard Times”

mixed-media (acrylic paint, dirt, embroidery thread)

The following quote is about providing support to other farmers during the “hard times,” the farm crisis of the 1980s.

--Lora

Quote (within artwork) by Jake Geiger, Farmer, Robinson, KS 11/28/99:

I was friends with everybody. I didn’t turn anybody away. I never turned anybody away that wanted support. And I went out of my way -- reached out of my way to help a lot of people. I did a lot of things. I mean I knew what it was like to be in trouble. And I can tell by looking at people if they were -- if they were -- if things were really rough for them. And I’d go out, I’d reach out to help them when I could... I can’t tell you. You go to them -- if they’re really down you put your hand on their shoulder.

You give them a hug. You look them in their eye -- it’s a physical thing that you have to experience. You can tell, you know, by the look on his face if he’s beat. And you can tell -- you get so you can tell by the look on his face, you know, how close he’s getting to blowing his head off. And you’ve got to figure out that whenever he gets that close, well you better go do something if you can. Now I say this to you. It’s not simple. It’s not simple. But you get so that you can judge a lot of things and people.

And you have to try -- to me the essence of Christianity is humility and charity. And you have to try to be charitable to people. You have to try to be kind to people. So anyway, all kinds of things happened. All kinds of things happened.

--Jake Geiger

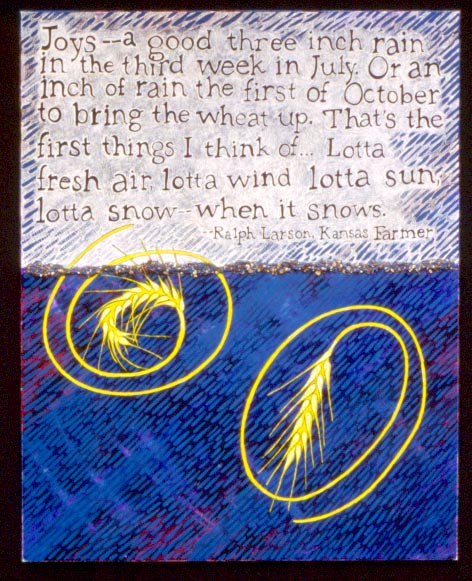

“Joys of Farming”

clayboard with ink

I’ve always liked the animals, the domestic animals and the wild animals that were part of our environment, and being able to walk on ground instead of pavement. To see the sky without really being dimmed by city lights. So the country farm lifestyle is great.

--Joyce Larson, Farmer, Scandia, KS 12/18/99

I’m a loner, I like to be out there alone... Closest to nature -- that’s -- go out and set out on a hill if you ever get time and just look off into space and just -- just look.

--Bill Tobald, Farmer, Glasco, KS 12/15/99

I guess my biggest joy is that I have two boys, one is a sophomore in high school and the other one is a sixth grader. And my joy is when they come out and we work together on different things, and the work ethics that they can gather on the farm there. And I think that it’ll be passed on to ‘em for their -- whatever career that they go into I think it’ll help ‘em there. And -- and it just -- it’s just a great sensation for me to see my oldest boy, especially, go out and jump on a tractor or the combine.

--Neil Becker, Farmer, Mankato, KS 12/17/99

Quote (within artwork) by Ralph Larson, Farmer, Scandia, KS 12/18/99:

Joys -- a good three inch rain in the third week in July. Or an inch of rain the first of October to bring the wheat up. That’s the first things I think of... Lotta fresh air, lotta wind, lotta sun, lotta snow -- when it snows.

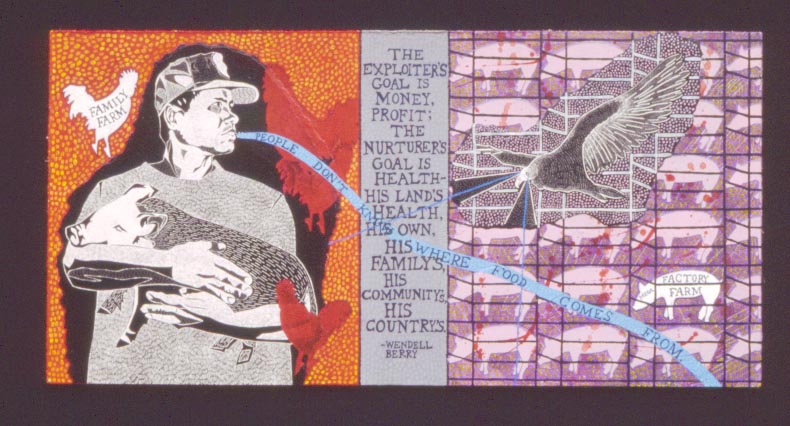

“Family Farm Versus Factory Farm”

mixed-media (scratchboard, acrylic paint, collage)

Quote (within artwork) by Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, 1977:

The exploiter’s goal is money, profit; the nurturer’s goal is health -- his land’s health, his own, his community’s, his country’s.

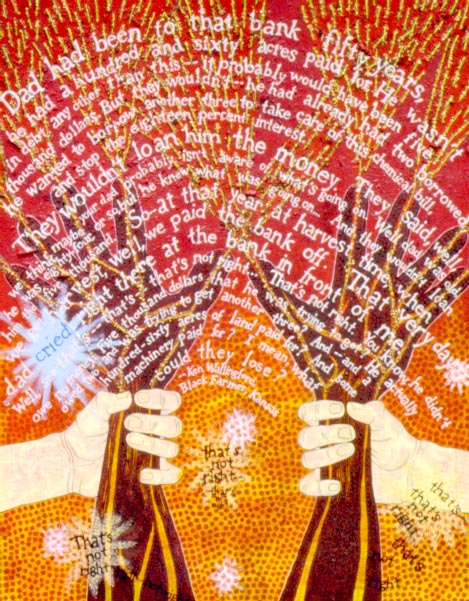

“That’s Not Right”

mixed-media (acrylic paint, dirt)

I spent several hours with Ken at his home in Effingham, Kansas. Ken is an African-American farmer, and he is now part of a class-action law suit seeking reparations for discrimination because he -- like many black farmers -- was denied farm loans from the government when their white counterparts received them. I tried to represent this discrimination as a subtle form of violence, where the white hands are squeezing the wrists of the black farmer’s hands. The quote in this piece is taken directly from an incident that Ken told me about where his eighty-four year old father was denied a bank loan for five thousand dollars from a bank he’d been going to for fifty years. About this incident Ken said:

That very day dad cried right there at the bank in front of me, cause the banker -- you know. Well see, that’s -- that’s -- that’s not right... That’s not right. You know, he didn’t owe no money. Five thousand dollars that he was trying to get? He actually owed two and was trying to get another three? And a hundred-sixty acres of land paid for? And some machinery paid for? I mean, what could they lose?

Complete quote (within artwork) by Ken Wallingford, Farmer, Effingham, KS

12/6/99:

Dad had been to that bank fifty years, he had a hundred and sixty acres paid for. He wasn’t in debt any other than this -- it probably would have been five thousand dollars. But they wouldn’t -- he had already had two borrowed, he wanted to borrow another three to take care of this chemical bill, and stop the eighteen percent interest. They wouldn’t loan him the money. They said, well, we think maybe your dad probably isn’t aware of what’s going on. Well, dad was old, he was eighty-four, or so, but he knew what was going on... And they wouldn’t loan him the five thousand. So -- at that year at harvest time, when we get harvest, well, we paid the bank off. That very day dad cried right there at the bank in front of me. Well, see, that’s -- that’s -- that’s not right... That’s not right. You know he didn’t owe no money. Five thousand dollars that he was trying to get? He actually owed two and was trying to get another three? And -- and a hundred-sixty acres of land paid for? And some machinery paid for? I mean, what could they lose?

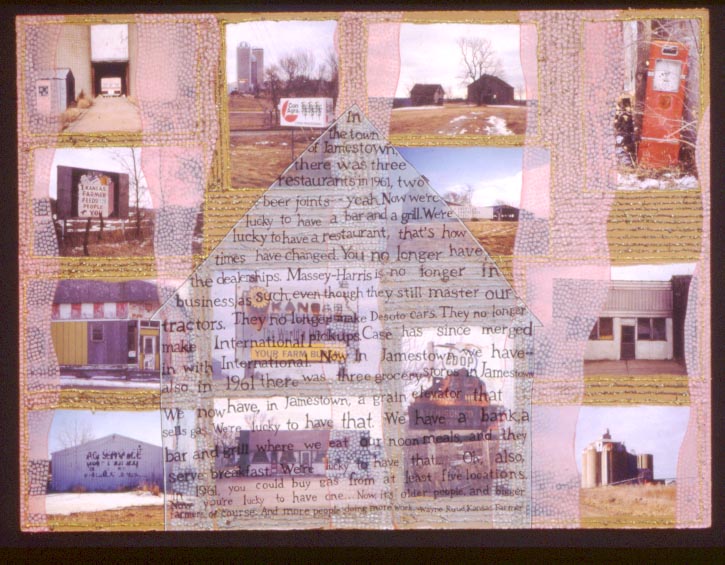

“In Jamestown”

mixed-media (photos, acrylic paint, dirt)

Quote (within artwork) by Wayne Ruud, Farmer, Concordia, KS 12/16/99:

In the town of Jamestown, there was three restaurants in 1961, two beer joints -- yeah. Now we’re lucky to have a bar and a grill. We’re lucky to have a restaurant, that’s how times have changed. You no longer have the dealerships. Massey-Harris is no longer in business, as such, even though they still master our tractors. They no longer make Desoto cars. They no longer make International pickups. Case has since merged in with International. Now in Jamestown we have -- also in 1961 there was three grocery stores in Jamestown. We now have, in Jamestown, a grain elevator that sells gas. We’re lucky to have that. We have a bank, a bar and grill where we eat our noon meals, and they serve breakfast. We’re lucky to have that... Oh, also, in 1961, you could buy gas from at least five locations.

Now you’re lucky to have one... Now, it’s older people, and bigger farmers, of course. And more people doing more work.

December 2001

vol. 56 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents

December 2001

vol. 56 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents