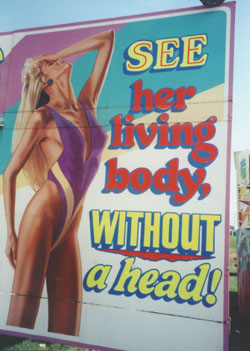

Photo by Fred Nelson, 1994

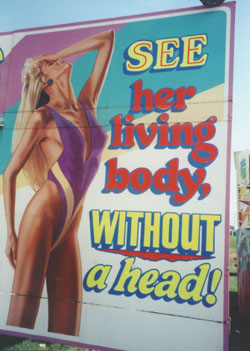

Photo by Fred Nelson, 1994

March 2000

vol. 55 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2000

vol. 55 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

Keith Ratzlaff's poetry has received national attention since his book length manuscript, Man Under a Pear Tree, was selected by poet Robert Dana for the 1996 Anhinga Prize for Poetry. His second book of poems, Across the Known World, was published in the same year by Loess Hills Press. In addition to two previous chapbooks, Ratzlaff's poems have appeared in major poetry journals including Poetry Northwest, which awarded him its 1996 Theodore Roethke Prize. Originally from Henderson, Nebraska, Ratzlaff earned his B.A. degree from Bethel College, and his MFA from Indiana University. Now Associate Professor of English at Central College, in Pella, Iowa, he teaches writing courses and, he claims, bowls an average game of 144.

As the resonant titles of his two recent books suggest, his work offers a series of maps for

varied geographies--the regionally defined landscape, the personal territories of memory and

body, as well as the conceptually wide spaces of liberal-arts knowledge. Visual art becomes a

kind of topographical map, layering the relations among all of these areas of inquiry in Man

Under a Pear Tree, which draws its title from a painting by Paul Klee (1887-1940), and

maintains an ongoing relation to Klee's paintings referentially throughout the book. However,

the paintings do not appear in the book, with the exception of one image on the cover, Klee's

"ach, aber ach!" Mennonite Life now offers readers the opportunity to enter these poems in Man

Under a Pear Tree through several kinds of interpretive maps: by reading a recent interview with

Keith Ratzlaff, listening to the poems read by the author, and examining images of Klee

paintings which are relevant to the book.

Reading: wav file (15 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (616 KB)

August and pears falling.

It's as if I've gone

blind, as if my life has been.

As if I were a boxer pummeled

and pummeled

with soft, left-handed jabs.

There's a radio somewhere,

a parking lot,

a boy singing along

his voice like a great mallet

beating a car engine.

"Oh," they sing, the boy and the radio,

"oh and oh baby." It's as if

pears were breasts

if breasts were like that,

like rain on a day I remember

when the everywhere nature

of rain was on my face, in the trees,

in my hands outstretched.

As if I had

climbed the pear tree

with one part of my body and

shaken the limbs

for the delight of the rest of me.

One fall I climbed the ridge,

acorns dropping

in the oak leaves like gunfire --

but this is not like that.

Pears fall,

and what green is left

leaches quietly into the air

just before

they hit the ground.

Then yellow, then blush pulled

into the earth

like multiple lovers -- if pears

and the everywhere nature

of seed and fruit

can be imagined that way.

As if blindness were a cure

and delight

for the eyes; as if

the blind man hit

by lightning

in his own back yard

had his sight restored

as a curse.

I am not in danger.

Reading: wav file (19 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (773 KB)

There's beer on the table

And the woman with red hair is thinking

What if the door opened

What if the roof blew off

What if the whole bar didn't have its arms in the air

watching the playoffs

What if she broke into flames

The whole bar, its arms and fists in the air

as if this were Fidelio and tragic

And wishing it could happen: flames, corolla, ash,

and none of it her fault.

Someone else has been looking over her shoulder

all day, mimicking her

The way pearls on a string mimic each other

The way a dancer's movements in one stopped moment

finally rush up to be her and now

And she's thinking of apples

the moment before the moment they hit the ground

Thinking of the old woman in the street

kneeling in the traffic, praying, her voice raised

Of a female house finch faking a broken wing

Of the woman in traffic with her eyes closed,

her green tam, the blue of her eyelids

Wishing then that God would simply lift her out

And thinking, this self at any one moment,

the man who survived being hit by lightning

seven times, who then committed suicide

And the glaze on the road going home

The picture her daughter drew of a house

some clouds, two ankles, two shoes

disappearing off the top of the page

It's a woman flying above our house, the girl had said

And thinking of the abstraction, the new stage

it signaled in her daughter's development

The five simple lines around the shoes that mean motion

and up and trailing away

And wishing it might be her, the woman flying

blessed for no reason with a great invisible gift

Q: Your poetry seems to me to hint at the meditative side of the Mennonite farmer, the "man

under the pear tree," never pure farmer, always part thinker, ambivalently torn between his

feelings of loss and his feelings of his own growth, his own ripening. Given the historical

moment, I want to position him as a millennial figure in the text, along with another potentially

millennial figure, who might also have a relation to the Mennonite past: the woman of the last

poem, closing the text in flight out of and above the house. In these senses your poetry

documents sadness while gesturing toward "a great invisible gift." The gift of change? Perhaps

cultural change?

A: My first recollection of anything millennial was in the "end of days" context of conservative Mennonites I grew up with. One family in town, I think, had the entire history of the world on a chart, beginning to end. They didn't claim to know the exact date of Christ's return, but you got the impression they had a pretty good idea. I've always been jealous of--and alarmed by--that kind of certainty.

I shouldn't be proud of this, but my ambivalence often seems to find its real twin in Robert Frost's. Frost's speaker in "For Once, Then, Something" looks and looks into the well's depths but sees only reflection. Then the one time he thinks he sees "something white, uncertain" in the water it's so vague he's only left with a "something"--but something nonetheless.

If characters in the poems are "millennial" it's by the accidental context of the times. I

think the last part of the 20th Century--the time I've been alive--has been lived under the gloom

or promise (take your pick) of the millennial, but so has most of the last 1000 years. I do hope,

though, there's at least a hint of my own sense of grace to both the characters you mention. For

what it's worth, both the man under the pear tree and woman in the bar speak about their

"something's"--their "gifts"--in the subjunctive, wishing for them rather than actually holding

them in their hands.

Q: It is irresistible to ask you a millennial question related both to poetry and to Mennonite Life,

since this interview will appear in the first issue of this newly online journal existing in the

highly visual, spatial world of cyberspace. What is your take on the forms and needs of poetry at

this historically interesting time?

A: It's obviously exciting and flattering to be translated into cyberspace (whatever or wherever that is). The lateral connections you can make with computers and the web are models for the kind of liberal arts mind we've preached in higher education since the Greeks. I hope these types of connections are reflected in the method of the poems in Man Under A Pear Tree, but you see this kind of thing in other poets, too, the need to include, to pile up what we know and try to unify it. I'm thinking here of poets like Jorie Graham or Gerald Stern, and also of Jeff Gundy's Inquiries and his latest work.

I read in the paper the other day that poetry is "hot," with some small poetry publishers even making money! Imagine. The truth is most major publishers--Oxford University Press only the latest--have suspended or canceled poetry publishing. For the most part, poetry has never had a wide readership. Imagine any poet at any moment in history who could draw even a fraction of the average National Basketball Association audience--15,000 people paying $50 a seat. Plus Cokes and hotdogs. The strength poetry has always had is intimate: the connection between the poem itself and the individual reader, no matter how the poem is delivered. The poems I love best are still the ones where I find my own voice meshing with that of the poet; those are the ones I read aloud to myself and my students.

As far as Mennonite Life and this inaugural issue, I don't know if what we're doing is

really different in kind, even though it's surely more efficient, easier, faster. The danger as

always--I'm going to go off on the usual rant here--is that we become passive, make a virtue of

simply connecting things up without thinking through the connections. Maybe right here in the

interview--at this point on the screen--there should be a place for the reader, viewer, web crawler

(you ARE out there, right?) to click if they'd like to read the poem aloud to someone else

in the room, or click if they'd like to copy the poem down with a pencil in their own hand

writing in their journal.

Q: Man Under a Pear Tree, the title of this 1996 book, wraps this collection of poems in a highly structured, referential relation to the work of Paul Klee, most clearly to the 1921 painting by that title. An epigraph from his Pedagogical Sketchbook further opens this collection:

Revelation: that nothing that has a start can have infinity.

Consolation: a bit farther than customary!--than possible?

How did your interest in the visual experiments of Klee come to shape this book?

A. I'd been living in London, England for two years and I was going through what I thought of then as a crisis. I'd been forced to change the way I spoke to make myself understood to my English colleagues. The nasal short "a," for example, that is part of my Henderson heritage had to be swallowed, refocused into my throat; I had to use more air and talk more softly--not to sound British, but just to keep people from cringing. The American Midwest accent sounds to British ears, I think, much like the Australian one sounds to us.

In the same way, the poetic voice that I'd learned from American poets I

admired--William Stafford, William Kloefkorn, James Wright, Richard Hugo, Robert

Frost--seemed odd and flat and parochial and unrelated to the urban, international, theatrical,

artistic world I found myself in. (Of course none of these poets are really flat and parochial but I

thought so at the time.) I literally stopped writing. Then I saw an exhibition of Paul Klee's work.

Immediately--I still have the notebooks from that day--I was struck with Klee's humor and

playfulness, the endlessly inventive and serious use of materials, color, form, language, story.

These seemed to point a way out of the narrative, regional box I had locked myself in.

Ah,

Reading: wav file (5.7 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (733 KB)

it was worse before.

Now I have learned

to open one eye,

now my hair has turned

into its own comb,

now my heart is

inseparable from my body.

It is all so much gravity

stacked at the end of a board;

it is all so much fulcrum

to have grown so light

that small and uncentered

things are my equals.

I have grown so light

snow could tip the scales.

Take the cover drawing of the book--"ach, aber ach!" The imagery in the first stanza can be seen in the picture: comb, hair, eyes, heart. But what interested me most was that little squib of black ink at the bottom left. Without that small touch, the huge head would topple over from its own weight. That balance, the pathos of that vulnerability, is the point of the picture for me, and the point of the poem. That was a completely new way for me to set up the tensions and voice of a poem.

In the section of the Sketchbook I took the epigraph from, Klee is lecturing about the form of the arrow in drawing, its strengths and limitations. Even with all its energy and movement and promise it can't overcome its built in inertia. And humans, of course, are like arrows: "Half winged -- half imprisoned, this is man!" he says.

The "revelation" is really no revelation--we know we are alterable, and that we die. But

the "consolation" has two distinct emotions you can hear if you read it aloud--the dramatic

exclamation we all make at one time or another, a bravado that says we will achieve something

more--go "a bit farther than customary!" Sound and fury. And the softer, wishing question that

implies the real and paradoxical revelation--that there's hope even if it's impossible to go

"further than possible."

(image removed due to copyright restrictions) Paul Klee (1879-1940) Athlete's Head Watercolor, gouache and pencil on laid paper mounted on light cardboard, 1932. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1987. (1987.455.20) Photograph © 1985 The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Reading: wav file (19 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (733 KB)

At the fairgrounds

a women With the Body Of a Snake

will speak to you for three bucks

and you pay it, even if it is only

an Amazingly Real Illusion. Poor body

disclaimed like that, poor head

for three crappy bucks. And

for three bucks more Tracy Steele,

the Voluptuous Centerfold Model,

decapitated in the car accident,

her body Kept Alive! A Medical Marvel!

will stand and walk around, the barker says,

and why not? What other purpose is there

than travel and glamour and the fair?

It's 1932. Paul Klee has left the Bauhaus

and is cooking veal and cauliflower

with grated cheese and butter in Düsseldorf.

"Such a meal stimulates me mentally," he wrote

his wife, Lily. "Afterwards I feel

especially healthy and not at all sleepy."

In Düsseldorf, in a portrait of an athlete,

it would take Klee only 4000 dots of paint

to separate the athlete's head

from the athlete's body -- and the brain

from the head as if it could be removed

and why not? Think of the woman

who plays Tracy Steele's body,

who jitters in her hospital gown as if galvanized,

whose body has been removed from her head

if only for 5 Big Shows A Day,

someone who could pull back the little drape -- Ta-Da --

and reunite the body and the mind

and why have they been apart for so long?

But she doesn't, and she usually has Monday off.

What if she were to jog in the park,

anonymous like all the rest of us,

our bodies running by themselves,

silver stars falling,

no one's head doing much of anything --

thinking of recipes or dogs or

rerunning that hackneyed movie

in which the body is famous

and athletic and safe --

How Would We Know It Was Her?

Q: Focusing on the poem "Athlete's Head" in relation to the painting brings into focus a central theme running through the book: that the body is where we live and suffer, and yet its metaphoricity, its richness, its structures are intellectually--and hilariously, in this poem--elusive. Through subject matter ranging from pop-cultural fetishism, to cancer, to racial violence, the troubled treatment of suffering bodies and souls comes up over and over again in this book, from "The Body Pledges its Allegiance" to "Gospel," which features "the first day my body discovered / its real predicament / and sent my voice out for help."

How do you approach the body in your work?

A: Klee thought you didn't use your mind in sports and so didn't have much time for them. What would the Bauhaus football team have been called--the Fighting Functionalists? By the way, did you know that there's a college in California--Whittier College--whose athletic teams are nicknamed "The Poets"? Could you yell, "Smash 'em up, Poets," with any conviction?

Anyone who grows up in a farming community knows how vulnerable the body is: I think in national statistics farming is rated the most dangerous occupation--more so than mining or police work. I'm thinking here of my uncle who nearly lost his arm (and life) when he caught his sleeve in a power takeoff shaft. But any rural place would have its own stories. I didn't set out to write a book of poems about the body as the place we "live and suffer," as you say, but that's obviously the battleground of the poems in the first section. A cynic would say I wrote the poems because I had just turned 40 and needed to vent my anger at my first real back pain and first pair of bifocals. Maybe so.

Photo by Fred Nelson, 1994 |  Photo by Fred Nelson, 1994 |

Before I wrote "Athlete's Head," I'd just been to the Iowa State Fair and had seen

sideshow signs for the Tracey Steele show. (A friend later actually saw the show and so my

descriptions of it are second hand.) The body of the woman in the show is a different sort of body

than in the rest of the poems, silly and American: A centerfold model reduced to just her body,

her sex; the body then rescued by technology; then re-commodified in an even worse way than

the original centerfold. The most honest (and best) part of the whole thing is that everyone knows

it's a con.

Q: Your exposé of the visual con in this poem seems to me to be related to one of the poems in

the collection that I find to be tremendously powerful. "Gladiolus" is such a loving poem, first

giving an exposé of forms of racist historical violence perpetrated upon the black body, and then

honoring the integrity of the body and the metaphoric resonances of all the Latinate words used

to anatomize it. And, the poem is packed with visual images all the way through.

Reading: wav file (16.6 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (675 KB)

There has never been a shortage

of places the body wanted not

to be: in the lifeboat,

at the awards dinner, under the tree

after falling, in the tree hanging,

in the box, in the box exhumed.

Or here in a photo on an inside page

of the Times: a skeleton

from the African Burial Ground, hands

folded across the now-collapsed chest.

A gesture, the Times says, meant

to help the spirit find Africa

again. And now scaphoid,

the wrist's bone boat, rides

in what was the heart's little harbor.

And cuneiform the wrist's wedge,

and semilunar the wrist's half moon

rises over the ocean. Remember

how often the torso was just bloody

cloth, the groin a red triangle,

the arms fired and set adrift.

That's over. Now fingers, wrist,

ribs, spine are mixed, all crossed,

all merely cups in the same cupboard.

But spirit you were right all along --

the journey is a map of the body.

Here in the backwash of the chest,

above the Inlet of the Pelvis,

north of the great and nameless

Os Innominatum, here at the sternum

you crossed your two lucky arms

at the middle bone called Gladiolus --

north of Ensifor, the false one,

south of the Manubrium -- Gladiolus,

also called the sword of the body,

once called the wild iris of Africa.

A. On the same day I'd clipped the photo the poem mentions from the New York Times, I was--for whatever reason--browsing a copy of Gray's Anatomy. I know some teacher of mine, somewhere, must have told me this, but I'd never realized that the Latin names of bones are metaphoric--except for the Os Innominatum (literally the bone with no name), because whoever was in charge of the skeleton that day couldn't come up with anything it looked like.

I thought it was poignant that those who buried this person must have crossed the body's

arms in a secret sort of gesture that would let the spirit transcend geography. And my own map

tries to use the history of the word "Gladiolus" itself as a way "home."

Q: Your snapshots from sideshow advertisement really are evidence of how important the role of

the visual world (and visual blight) is in your work. The technical term for a book of poetry

interacting so deeply with visual art is ekphrasis: as Grant F. Scott suggests, "it is the genre

specially designed to describe works of art, to translate the arrested visual image into the fluid

movement of words" (xi). Scott derives his terms from the Laocoön, which famously presents

visual art as a static representation of subject matter in spatial terms, and verbal art as the

unstopped, temporal, always fluid medium. As we gaze at the ekphrastic poems in this book,

listen to them, and gaze at the paintings from which they come, how would you position your

work in relation to this art-historical problem?

A: I suppose Keats' urn is the great ekphrastic symbol in English literature--the static moment held forever where love is never consummated, but also never dies. And the urn may well be a "friend to man" and "beauty may well be truth and truth, beauty" but it's also a "cold pastoral." Keats couldn't have known that his poem may well outlast the urn, but I'll bet he hoped it would. Those last two famous lines have always seemed to me less about the pottery and more about the poem itself.

I tried to use the Klee paintings more as starting points for language, the way any poet

might use trees or sunsets or the beloved or children. If they work, there ought to be a kind of

symbiosis, but it's almost impossible for me to judge that. Do the poems need the paintings? I

hope not. I don't think so. But I do hope--for my sake and Mennonite Life's cyberstatus--there's

a little shock of recognition, a broadening of context for both when they're seen together.

Q. Scott describes a sort of "Medusa" model when things don't even out--the weight of the art

stuns the viewer or the poems themselves, and sort of kills them off. I like to think that the

language of poetry, with its leaps and its open, multiple references, prevents the paintings from

becoming too weighty or powerful.

A. I never wanted the poems to merely "illustrate" the paintings. That leads to Scott's real problem--that the art simply outweighs the poem, becomes the sole reason for the poem's existence. What fun could that possibly be for a writer or reader? That the plastic arts--and music and dance, too--are more immediate is a given. But poetry has, in addition to the "fluid" attributes you mention, the advantage of being spatial, aural, oral--even tactile in the weight of a book, the texture of the page--so I think things even out.

(image removed due to copyright restrictions) Paul Klee (1879-1940) Rough-Cut Head Black ink wash and pencil on wove paper mounted on light cardboard, 1935. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984. (1984.315.55) All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Reading: wav file (17.3 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (704 KB)

When the woman in the purple trousers

on the bicycle -- now at the corner

now up the street now by the sign

now by the tree -- turned the corner,

I thought of her in the dual wind:

the cold one from the west today --

and the other wind beginning with her,

spreading out behind her like geese.

I thought about her flying hair

and the cowl of her skin

and her forehead

defined and reddened by the wind,

of her lips defined and burnished

by the wind. And how even on a bicycle,

how easily we breathe and how easily

our wondrous heads are invaded by the wind.

How open and hollow are the mouth's courtyards,

or the sinuses, or the hallways of the ear.

How vulnerable. How much of us is absence

like drawers, or pictures of absence --

the sky in photos of clouds at night,

the outline of a breast in an x-ray

taken before the mastectomy.

How easy it is to find a place in the skull

for the chisel, or the gun, or the wind

and its glitter. We are alterable.

I know a plastic surgeon who put the gun

in his mouth, fired, and lived.

Think of the echo. The brain in its great hall

banqueting, then besieged. And the joy of impact --

the eyes unbolted, shifting, siting new stars

in the new red sky, the jaw turned to grit

and glitter the wind would fling at us later.

He was depressed for reasons he couldn't name.

In woodshop he has made a letter holder

covered in curious purple spangles.

Q: When I showed a slide of the painting "Rough-Cut Head" to the poetry workshop class, while interpreting the poem, students commented on the seeming fortress-like monumentality of the head in the Klee painting. They were fascinated with the poem's reshaping of the head into a structure with vulnerable spaces: "How open and hollow are the mouth's courtyard's, / or the sinuses, or the hallways of the ear. / How vulnerable. How much of us is absence." For me, the translation of the spondees "rough-cut" from hewn to abstractly drawn and therefore transmutable can be a great thesis of this book (despite your earlier note that such knowledge is not necessarily a revelation): "We are alterable," the poem asserts, capable again of producing our own desire for death, even for great devastation, and then of recasting it again as a desire for growth.

In the class, we were all fascinated with the story of the cosmetic surgeon who would

know better than anyone else the structure of the head, and who thus would feel its devastation,

and its survival so very strongly.

A. When I looked out the window one morning, my neighbor across the street was riding her bike, wearing really brilliant magenta slacks that made her the brightest thing in the neighborhood. My eye simply had to follow her. Klee's painting was on my desk and the rough, faceted head became a way for me to link that small initial meditation with the story of the "sculpting" done by a plastic surgeon who was on the ward when I worked at Prairie View Mental Health Center in Newton, Kansas. The "head" of the painting becomes a theme I can play variations on. Except for the title, there's really not much of the painting in the poem, but that title is crucial. Like most of the people who are "altered" in the book, the plastic surgeon's message--his art, I guess--of "spangles" at the end is enigmatic to the speaker of the poem.

(image removed due to copyright restrictions) Paul Klee (1879-1940) Winter Journey Watercolor and transferred printing ink on laid paper bordered with black ink mounted on light cardboard, 1921. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984. (1984.208.5) All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Reading: wav file (29.5 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (1.17 MB)

This is the boy next door discovering

what he wants his voice to do --

that his lungs in the cold

and throat and teeth and tongue

can mirror alarm if he likes.

He fakes a bicycle crash on the ice,

jumps up, and yodels his imitation of a siren.

This is the red folder blown open in winter.

This is the street under a window.

Inside Schubert is at the piano,

singing Die Winterreise for the first time

to friends: "Never again will the leaves

be green at the window. Never again

will I hold my love in my arms."

And they hate it.

This is Paul Klee's Winterreise,

a portrait of the artist one-eyed,

caped and hooded at his mother's grave.

This is Klee's mother on the way to his studio.

This is Schubert in the November marigolds.

This is the boy outside my window

making the journey again and again

down his driveway, pedaling hard on the ice,

staging his accidental death,

rising and singing like an ambulance.

This is the white fog changing to yellow.

This is Klee's mother after tea in his studio.

This is Schubert dying of syphilis.

This is Schubert singing to the crows:

"Krähe, crow, even if you want to leave me

don't leave me. Don't leave me."

This is Ida Klee walking into Klee's studio

after tea on the day she died.

Klee was in his chair, asleep.

Evergreens were on the horizon.

This is Ida Klee released from paralysis,

This is her ghost walking the studio

after tea, after she had died,

winking at her son as if it mattered --

that kind of message from the dead --

winking at Klee, who was not surprised,

who for the rest of his life took it seriously.

This is the folder blown open in winter.

A week later Johann Vogel sang

Die Winterreise to Schubert's friends

and they listened

and loved it this time.

This is Vogel's baritone in the marigolds,

the wondrous conduit of his throat

and mouth, diaphragm, teeth and lungs.

These are the crows who throw snow

at Schubert's scorned lover

from every roof of every house in town.

There are accidents of the flesh;

there are the unbalanced lovers

we have been and still are.

Yesterday the twist of sunlight in a room

filled me with longing.

This is me putting on my coat,

walking downtown to sing

Christmas carols in the open square.

This is Klee painting himself from memory.

This is the boy who has been dying all day

hoarse and unrescued, going in to supper.

I've driven by the same woman's house

for 20 years remembering she kissed me.

This is me in the December marigolds.

These are her father's fields blown full of snow.

Q: In the poem "Winterreise," I want to see the boy who "fakes a bicycle crash" and then imitates

the sounds of an ambulance as a cycle of play all day, and finally goes in "hoarse and unrescued"

as a millennial figure also--seeking solace in sound, singing in the winter of our many

discontents, knowing song is not redemption, but that it is one important way of seeking love,

and of responding to the partial, incomplete loves we experience in families, through deaths,

through winters. Is there a relationship to the Schubert song cycle by this name?

A: The method is again theme and variation, to try to literally keep four stories in the air at once,

like a juggler. I knew Schubert's song cycle, but when a commentator suggested that Klee might

have taken his title from Schubert, the connection seemed somehow right even though there's

nothing in the painting other than the title that would lead you to the music. As with most of the

Klee poems, it was only by linking up the two other "real" stories--the kid outside my study

window and an autobiographical bit about a girl I loved in high school--that the poem became

satisfying for me. I've fragmented the story lines to "disrupt" the narratives, but I never wanted to

lose any of the threads. Instead I wanted to cement the connections in a sort of democratic form

that the anaphora of "This is" tries to underline.

Reading: wav file (15.7 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (640 KB)

Once I was a boy

in a classroom

of boys learning to play

the ukulele. In the end, even

the stumpfingered

learned three chords:

G, C, D7. Our big felt picks,

our whiny

little strings. We were a part

of the American Folksong

Revival

inspite of ourselves,

in spite of our penises

and voices

rising and falling like elevators.

Imagine us, our 25 faces

still forming,

heads slightly out of round,

singing "I Gave My Love

A Cherry,"

or "Big Rock Candy Mountain."

There was the recital

we never gave

because, to tell the truth,

we weren't very good.

One boy is dead

now, three are welders,

two joined the Navy, one

sells used cars,

half a dozen are farmers,

one has been convicted

of exporting

Nazi literature to Germany.

I don't remember any of us

as mortal

or talented or cruel.

All we ever learned was that

chord progression,

knowable and sequential --

beautiful as gears shifting --

something useful

and at the bottom of all

the music we imagined we

could care about.

We knew who Mozart was

but there wasn't any Mozart

for the ukulele.

That would have been wrong

and we knew it -- some of us.

Or none

of us. Either way.

Almost no one will remember this, but I started out as a music major at Bethel. I quit because--like the guys in the Ukuleles poem--I wasn't very good and hated to practice. So I like the idea that music isn't redemption but solace.

(image removed due to copyright restrictions) Paul Klee (1879-1940) Angel Applicant Black ink, gouache, and pencil on wove paper, 1939. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984. (1984.315.60) All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Reading: wav file (25.4 MB)

Reading: mp3 file (1.01 KB)

Because Paul Klee has stopped playing the violin

I am lifting my arms to heaven

Because in Switzerland you are nothing without wings

I am applying in place of Paul Klee, who lives in Switzerland

Once I applied in place of Mondrian

Because three is two put in motion

Because it is harder to apply in place of myself

Because obviously I was turned down

Once I applied as a man hanged in a barn behind a house

Cezanne painted in Auvers

I am not immortal enough

If I were given the chance to remake the world I would defer

If I were on a third floor balcony I would test the railings

The barn behind the house with the blue door

I am not sure photography is an art

Because Klee has stopped cooking, too

Where else would I go

From the hayloft there was a grand view of the green

Provence hills

The dry rope and the dry esophagus

Above my head starlings were in the rafters

There was the moon

I do not think irony has a place here

Van Gogh painted the same house -- but not with such

fervor

Because not everything is up to me

Not like Cezanne

Who signed his paintings with a little gallows for years he

was so pleased

The rope and the twisted nature of the cedar

Pisarro and Cezanne in the clear Provence air. Their pallets

slowly brightening

Because he cannot swallow solid food

Red for Pisarro, blue for Cezanne

Because Klee has given me three arms to raise

Because I will have to apply next as a woman in a late Picasso

etching

And nobody wants that

Three arms

The moon above me

I had always been told birds living in your eaves were a sign of

good luck

But I don't know why

Because in the Talmud, a man turns into a worm but I am not

Where I am the ground is mottled; the room is small and the

flat has sheets hanging in the hallway

And my legs are vague

And because the moon

Who dies in photographs? At what moment?

If I thought there were a chance

Because the moon

Is pulling my head up into the first prong of a crown

Q: In the poem "Angel Applicant," I love the idea of an artist being an applicant to be an angel--and I also love the idea of any of us, out there struggling with meaning in our lives, being such an applicant! Certainly the recent spate of angel movies resonates with the image of angel applicants as well.

Yet this is the most discontinuous of the poems, and perhaps the most disturbing of the

paintings. The narrator in the poem, when applying to be an applicant in person, "obviously was

turned down" in the beginning. By the end of the poem, the moon appears to pull the arms of the

pictured applicant toward itself, as if by gravitational, lunar pull, like the pull of the moon on the

tide, or upon female physical cycles. Is there a nature theology connected to the system of art

perceptions pictured here?

A: Klee knew he was dying from scleroderma (a disease where the connective tissues of the

body thicken and harden) when he painted this in 1939--and he painted or drew 50 angels in the

last two years of his life. It's hard not to see this late one as a kind of self-portrait; Klee's angels

always seem to be caught in transit--half in heaven and half on earth, unable or unwilling to

make the leap. The speaker of the poem--the applicant--isn't really interested in saving Paul

Klee, but in getting into heaven any way he can. The semi-tragedy is that he can't seem to find

the right modernist art persona that the immigration folks in heaven will accept. By the end he'd

even try applying as a "real" person in a photograph. This angel is certainly one of Klee's ugliest.

That the "applicant" seems to have begun the transformation into angel at the end in spite of his

ugliness wasn't meant as anything more than a small bow to the idea of grace--and perhaps my

joking way to elevate Klee above other modernists who can't seem to get their subjects into

heaven.

The moon is just the moon.

Q: Yes, I grant that perhaps the flailing critic will just have to live on the real earth! I do think

your comment on a "small bow to the idea of grace" is all the more important for the modernist

context, which, as you suggest, tended to limit or critique gestures toward transcendence. Along

these lines, you commented earlier that the body is the ground, even a battleground, for one

section of the book, and the last section of the book seems populated by a number of angels,

restless and middle-aged, speaking to "God, who was once behind the door," as in "Fitful Angel."

What kinds of ideas and images ground or shape the second and third sections of the book?

A: The structure of the book was just a matter of corralling poems with similar interests. In the

first section I meant to treat the body in general--I wish there were a better metaphor than

"battleground," but that's the idea. The second section I saw as more narrative, more connected to

the actual "me" (whoever that is), more related to, as Johnny Carson used to say, "my boyhood on

the plains of Nebraska." I wanted the general arc of the last section to go up, to lean toward the

redemptive if not actually get there.

Q: Your invocation of Klee's Pedagogical Sketchbook in the epigraph of your book suggests a

theoretical line of thinking. Klee's theories suggest that the act of looking/interpreting is an act of

constructing the object as well as simply perceiving it; all acts of perception involve editing or

other actions. No act of perception is purely passive and innocent. Yet, the Pedagogical

Sketchbook emphasizes in bold print, "The eye travels along the paths cut out for it in the work."

Would you like to comment on the relation of your poetry to contemporary literary theory?

A: No. Or instead, let me use the Pedagogical Sketchbook examples to try and answer. The Klee of the first quote is the teacher intent on helping his drawing students understand how readers/viewers make meaning or "continuity" as he says later. "Meaning" is the joy that readers, viewers, listeners have made since the first story was told, or the first picture was scratched onto a cave wall, or the first song was sung. That it took until the 20th century for theory to catch up to this notion tells you something about theory. But it's a good thing we've finally recognized the basic truth: Readers will own poems they love and will interpret them, connect them to their own life stories, bend them to individual human need, will "love" them. We talk about art (and sports and politics) in these subjective terms all the time.

But no poet I know writes to make meaning, at least not initially. I write to make things,

to control the world in some modest way. One thing many of my beginning literature students

seem to believe is that poets are intentionally obscure. When students are really paranoid, they

seem to believe poets mean for them personally to feel stupid. But that confuses the reader's

problems with the writer's. I don't know any poet who is willfully obscure. When I'm in the act

of writing a poem--and during that first ur-reading writers do--I'm convinced there's only one

meaning for the poem and that the meaning is clear. Content isn't the issue, style is. Thus Klee's

emphasis--always in the Sketchbook--is on the how. Criticism and theory, interpretive acts that

rightfully belong to the reader, come later, hopefully traveling along at least some of the paths

the work has cut out for it. When it works right, the poet and reader walk the path together.

Forgetful Angel (wav) (12.5 MB)

Forgetful Angel (mp3) (512 KB)

Gospel (wav) (14.6 MB)

Gospel (mp3) (595 KB)

My Students Against the Cemetery Pines (wav) (25.5 MB)

My Students Against the Cemetery Pines (mp3) (1 MB)

Surgeon (peeling an orange) (wav) (14.2 MB)

Surgeon (peeling an orange) (mp3) (578 KB)

The Body Pledges Its Allegiance (wav) (15.6 MB)

The Body Pledges Its Allegiance (mp3) (637 KB)