Bluffton students carry a flag in

Armistice Day parade in Bluffton, 1918

March 2000

vol. 55 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

March 2000

vol. 55 no. 1

Back to Table of Contents

This article is based on excerpts from Perry Bush, Dancing with the Kobzar: Bluffton College

and Mennonite Higher Education, 1899-1999 (Telford, Pa.: Pandora Press U. S., 2000),

copyright © 2000 by Pandora Press U. S., used by permission. All rights reserved.

Several historians have noted how what became standard peace teaching among American Mennonites in the twentieth century became firmly nailed into place in the period between World Wars I and II. Certainly, conscientious objection toward war had been foundational to Anabaptist understandings for centuries. Yet there had been a paucity of literature on Mennonite peace theology in the thirty-five years preceding World War I, Paul Toews has noted, and when the war came Mennonites responded in a variety of ways to the challenges it presented. Partly because of their searing collective experience in the war, in the interwar era Mennonite leaders refocused and redefined their peace teaching in a manner that left fewer gray areas for individual Mennonites to navigate. While, in the World War II era and afterwards, individual Mennonites would continue to enlist in noncombatant service, buy war bonds or work in defense industries, they would do so under less ambiguous disapproval from their church.(1)

Toews and others have articulated such analyses broadly, largely divorced from any particular context. The Mennonite academic and church community of Bluffton College in northwest Ohio would seem an ideal place to examine the validity of this larger argument on a local level. From its very beginning, Bluffton had been founded and led by a zealous and talented group of progressive academics. These were scholars and church leaders like college presidents Noah Hirschy and Samuel Mosiman, academic dean (and former Goshen College president) Noah Byers, and Bluffton's star history professor C. Henry Smith. Educated at prestigious universities in the United States and Europe, altogether these were men who had tasted the heady brew of mainstream, progressive American culture and found it good. Much of their life's very mission would be to take simple Mennonite farmhands and transform them into cultured Christian citizens. Assimilation, such progressives argued, was not a process that Mennonites should fear or try to stave off with silly mechanisms like dress codes; instead, assimilation was a prospect Mennonites should welcome.(2)

If there was a collection of Mennonite educators anywhere who seemed ready to forsake

Mennonite distinctives like the peace position, it would seem to be the scholars gathered in

World War I era Bluffton. The fact that the Mennonite peace teaching both survived and was

strengthened, both nationally and at Bluffton, speaks volumes both about its increasing

importance in Mennonite life, and also something about the particular and changing nature of

academic leadership in Bluffton. By comparing Bluffton in both the World War I and World War

II era, such an analysis should be rendered quite clear.

Progressive Mennonites and the Great War

In 1917, as the United States embarked upon holy war against Germany, it correspondingly launched into a vicious and high strung offensive against anyone it deemed as dissenting from that effort at home. The postmaster general routinely banned from the mails any publication he judged threatening, and the Congress passed laws such as the Sedition Act which made unlawful any statement which might be construed as disloyal. A huge war propaganda machine kicked into high gear, and a spirit of intolerance came to take on a life of its own among the American people. Labor leaders and war dissenters were lynched and beaten, the teaching of German outlawed from the schools, and vigilante mobs of "patriots" whipped up a frenzy of fear and suspicion against anyone seen as detracting from "one hundred percent Americanism."(3)

As members of a Germanic-derived religious group whose theology rooted them in pacifism, Mennonites appeared as doubly suspect. Especially in the Mennonite communities in the great plains, where their Germanic culture had held on the longest, individual Mennonites who had attempted to remain faithful to their tradition by refusing to buy war bonds, for instance, were tarred and feathered or smeared with yellow paint. In Ohio and West Virginia, Mennonite leaders were tried and convicted under the Sedition Act. Two Mennonite churches, in Michigan and Oklahoma, were burned to the ground, as was the administration building at the Mennonite college in Tabor, Kansas.(4)

Altogether this new climate, which burst upon them like a sudden storm, left Mennonite leaders confused about how to advise their young men. Some of them counseled draftees to take up the position of noncombatant service, in which they would join the army but be assigned to a non-combat position like a medic or hospital orderly. Mennonites giving this advice tended to be more acculturated church leaders east of the Mississippi, particularly those with the General Conference Mennonite Church. This group included a number of Mennonite college professors and administrative leaders. Other church elders told the young men in the camps to retain Mennonite teaching and stay firm in their rejection of all military service and orders. Draftees who accepted this advice found themselves paying a high price for such stands of conscience. Isolated away in army camps, they were raked raw with brooms, beaten with fists and court-martialed to lengthy prison terms when they disobeyed directives from officers.(5)

A Mennonite college would clearly need to proceed carefully in such an incendiary environment. Because of its own declining sense of German ethnicity, Bluffton's peril was not as great as that of Mennonites on the great plains. The College Record had not been printed bilingually since 1910, and in 1917 former president Hirschy observed from afar with regret that the college "has largely lost its German life and tone."(6)

Bluffton students carry a flag in Armistice Day parade in Bluffton, 1918 |

Byers was right to be nervous, for the specter of patriotic violence hovered not far away. The next month one of the newspapers in nearby Lima began to encourage mob violence against the pacifists at Bluffton. Vigilantes bypassed the college in June but visited three Mennonite churches in the county, placing American flags over their entrances and left notes warning congregants that their removal would be taken as a confirmation of their rumored "un-American sentiment."(8)

The college was able to entirely escape the dangers that threatened, however, because it mostly rung with enthusiasm for the war. To be sure, Mosiman defended traditional Mennonite pacifist principles where he thought they applied. He took pride in the fact that, by May, 1917 at least, no Bluffton College man, Mennonite or not, had enlisted for regular combatant service, and that two had enlisted instead with the Friends' war reconstruction unit heading for Belgium. The president affirmed the college would not give academic credit for army service. Because of his fear of the growth of militarism at home, he adamantly refused to consider the college's acceptance of a Students Army Training Corps unit on campus, despite evidence that it might attract students.(9)

On the other hand, believing his nation's effort "the cause of righteousness and justice," Mosiman threw himself and the college he led behind the war in every way short of contributing to actual combat, and sometimes did not draw the line at that. Immediately upon the president's declaration of war, he wrote his old friend, Ohio Governor James Cox, to offer his services and those of the college. "Believing it to be the duty of each citizen to bear his part of the burden of war and his share of the perils...assign me to any work that I can do," he begged. While suggesting in particular YMCA or Red Cross work, he also assured the governor that the Bluffton's student body stood ready "to do all that lies within their power to alleviate the sufferings of our soldiers and to inspire our young men in camp with high ideals, or to do any other work that they can do and to which you may call them."(10)

Bluffton students with newspapers reporting the armistice, 1918 |

Mosiman had little patience with Mennonite draftees who did not fully cooperate with officers, and damned as "wicked and foolish" advice from Mennonite Church (MC) and Amish leaders encouraging noncooperation with military orders. He took pride that none of the Bluffton men had done this, urging them not to engage in "hairsplitting" over military commandments to don "the uniform and such things." He likewise extended this kind of advice to a wholesale embrace of noncombatant activities at home, enthusiastically backing the extensive Red Cross activities and war bond sales at the college.(12)

Properly inculcated into the progressive spirit that now waged total war as its ultimate reform, students naturally followed where their president led. In 1919 Mosiman estimated that about 150 BC students had served in the military in some capacity, along with five faculty members. Several of these technically served as YMCA personnel, but Mosiman could not have been under any illusions that this agency remained very separate from the regular army. Former athletic director Oliver Kratz bragged that they were drilled by army officers on board their ship to France, and were considered as non-commissioned army officers. May, 1919 found Byers in France, teaching psychology at an American Expeditionary Force university there; when the army had assumed the contract from the YMCA, Byers was happy to switch employers. Music Conservatory dean G. A. Lehman was enrolled in the regular army, along with chemistry professor Herbert Berky, who served his country doing munitions research for the chemical research section of the Picatimny Arsenal in Dover, NJ.(13)

Students greeted such activities with acclaim, particularly celebrating the exploits of Pvt. Edwin Stauffer, who had won the Croix de Guerre for gallantry in battle and returned home in March, 1919 to a heroes' welcome from his fellow students. Throughout the war the Witmarsum breathlessly reported on the adventures of former student Pvt. Clayton Welty, following his boot camp experiences in the United States, through his embarkation for France, his wounding in the battle of Belleau Wood and the combat death of his brother, to his slow convalescence in a Brooklyn hospital, still coughing up blood and the bits of uniform that German bullets had smashed into his lungs.(14)

Bluffton student Wilmer Shelly in uniform in front of College Hall |

Throughout the 1920s, Mosiman and his faculty colleagues continued to solidify the college's peace commitments without blinking an eye. In 1922 they hosted a major conference of the three historic peace churches, and Mosiman's baccalaureate address that spring contained a ringing condemnation of warfare. The college joined the larger 1926 movement on college campuses protesting compulsory military training proposals, turning over the chapel pulpit to peace speakers and distributing pamphlets against this prospect. Mosiman even paid two visits to Henry Ford in an unsuccessful attempt to induce the automobile magnate to endow a professorship of peace for the college.(16)

This sudden peace advocacy in the 1920s can be read in several different ways. Mosiman and his colleagues clearly continued to reflect the analyses and agenda of a mainstream progressivism which had itself begun to express a profound disillusionment with war. At the same time, the apparent inconsistencies in the peace position of Bluffton College leaders also reflected the deep ambiguity and confusion about their church's participation in war-related activities expressed by a wide variety of Mennonites, from the top leadership down through the pews. In 1918, for example, no less a stalwart Mennonite thinker as the young Harold Bender--who would later spend much of his adult life as a dominant Mennonite peace leader--accepted a job making gas masks in a defense plant, and quietly determined to accept noncombatant work if called by the draft.(17)

Into the 1930s, however, partly because of these traumatic experiences in the war, Mennonite leaders like Bender, Smith and others began to sharpen their thinking about the extent of Mennonite participation in warfare. Bender and other MC peace activists like Guy F. Hershberger and Melvin Gingerich took a leading role in rethinking the peace commitments in their denomination. In 1935, these three leaders performed key roles at a landmark conference on War and Peace in Goshen, where Hershberger clearly anticipated the fundamental outlines of what would be the wartime alternative service program of World War II, the Civilian Public Service system. In 1937, Bender, Hershberger and Orie Miller pushed across a new MC peace statement which reinforced the Mennonite commitment to conscientious objection and condemned the former gray areas of participation in noncombatant service, war-related YMCA or Red Cross work, war bond purchases, or defense employment. For his part, Bluffton's Smith began to temper his progressivism, worrying instead about the rise of a new totalitarian warfare state which had begun to position itself as the focal point for all civilian loyalties.(18)

As the world once again darkened with war in the early 1940s, these same Mennonite

leaders would discover that, while such teachings would not command universal obedience from

the laity in the pews, they had at least clarified some of the grounds for ambiguity. Once again,

Bluffton illustrated the contrasts.

Total War, the Home Front, and Bluffton College

In his baccalaureate address on the eve of World War II, Bluffton's new president signaled that this time, the college would have a different response to the coming world cataclysm. As a graduate with the class of 1924, Lloyd Ramseyer had cut his intellectual teeth on the enthusiastic progressivism of Mosiman, Byers and Smith. As a young high schooler during World War I, he had desperately wanted to join the heavy artillery, and only his father's need for his help on the farm had kept him home. His peace commitments had developed later, during the national disillusionment with warfare in the 1920s. Two years into his presidency, in June, 1940, he left no doubt about where he stood. He condemned war as "one of the greatest enemies of man. It is not Hitler, Mussolini or Stalin that is our chief foe; it is war itself." With the peacetime draft bill of 1940 obviously in mind, he cried that "we are in danger of letting a vast military machine control our lives and our resources."(19)

Such an emphasis surely must have affected individual students who had to make their own decisions about war and peace. In the fall of 1940, Ramseyer noted that even quite a few non-Mennonite students leaned towards pacifism. Yet a sense of duty to the national community pulled quite strongly in other directions. In a questionnaire distributed by the Peace Club in March, 1940, half the students indicated their willingness to serve if drafted.(20)

Less and less were these simple, abstract questions. When the coming storm finally broke, students, faculty and college leadership alike would have to choose from a variety of difficult choices that would send them in opposite and sometimes dangerous directions. It also promised a different kind of difficulty for the functioning of a college. In the dark summer of 1941, as the US lurched towards war, Don Smucker phrased the key issue quite clearly to Ramseyer, hoping that "the Army, Navy, Marines, CPS and plain ordinary cranky Mennonites do not get the college down."(21)

Two days after Pearl Harbor, Ramseyer realized that colleges "primarily interested in maintaining Christian principles" faced a difficult year. One critical fact is that their young men might be drafted at any time. In a special meeting early in 1942, the faculty voted to cancel all vacations and set commencement several weeks earlier. They also decided that seniors who were drafted before the term ended could take comprehensive exams that might substitute for their remaining classwork. And to seize the initiative and declare their own position, the faculty instituted two new courses entitled "Biblical Teaching on War and Peace" and "The Economics of War and Reconstruction." They also reaffirmed "the position of the Mennonite Church in relation to participation in armed conflict...as the belief and practice of the College."(22)

The most direct and inescapable impact of the war on the college came not in new classes or hurried graduations but in the more fundamental matter of enrollment. With no student deferments, colleges and universities across the country quickly saw most of their young men leave. Young women also deserted the colleges, lured by well-paying defense jobs. Already by April, 1942, Bluffton's student enrollment had fallen by 25%, and that was only the beginning. In March of 1944 Jacob Schultz informed the board that they could count 93 students taking classes. The next year the number dropped even lower, to 77 students, enrollment totals the college had not experienced since its very earliest days. Professors commonly addressed courses of 5-10 students, and individual classes could barely round up enough members to work up a loud cheer. The Class of 1944 had consisted of 67 freshmen in the fall of 1941, but by the time they became juniors their numbers had dwindled to sixteen full-time students.(23)

When the choice finally came, most of them opted for military service. Of the 167 men listed in the "Bluffton's Boys in Service" chart in the 1944 Ista, 38 of them, or about 22 percent, were in CPS. In the context of 1944, these were not surprising totals, not even for a college which had upwards of forty-five percent of its students listed as Mennonites. In fact, they indicated a higher CO percentage than did the college's constituent churches; the Middle District Conference sent only fifteen percent of its young men to the CPS camps.(24)

Back on campus, students reflected some real ambiguity in regards to Mennonite peace teaching at a moment when their nation embarked upon a course of total war. The Witmarsum, for example, continued to reflect the diversity of viewpoints that had characterized the campus before the war. Editor Margaret Berky signaled the nation's entrance into the war with a firm plea for gracious tolerance of diverging opinions, and certainly the campus responded in kind. The paper regularly published regular letters and guest articles from former students, whether they were like conscientious objector Don Gundy, who called the college to a steadfast adherence to peace principles, or Johnnie Leathers, who wrote from Navy boot camp to express his pride in his own service.(25)

At the same time, many students held fast to the peace and service commitments that continued to characterize the college. Student Senate organized a War Relief Committee, which threw itself into activities like blood donations, and collecting clothes and gauze for relief and first aid. With Ramseyer's warm approval, the Peace Club expanded its energies considerably to include providing assistance to the men in the conscientious objector labor camps, the Civilian Public Service (CPS) system, and bringing to campus national pacifist leaders such as A. J. Muste and J. Nevin Sayre.(26)

The peace-minded students were following the lead of their president, who created a very different model of the college's commitment to nonresistance in wartime than had its leadership in the earlier world conflict. This president did not promote war bond sales or join such campaigns. He turned down a request from the Navy to run an advertisement in the Witmarsum, and no war recruiting posters or slogans appeared in the Ista. In contrast to Mosiman's open advocacy of the noncombatant position twenty years before, Ramseyer refused to counsel young men about how they should respond to the draft. Instead, he pointed to the college's peace position and urged them to serve their country "in the manner in which your own conscience dictates."(27)

Still, when he heard word that a former student was considering transferring from CPS into the military, he penned a scarcely disguised attempt to dissuade him, and when three former students did transfer to noncombatant service, the president wrote to a CPS administrator wanting to know why.(28)

In a nation at total war, continued dedication to peace principles was a sometimes risky business. In the fall of 1942, despite signals of opposition from many people in town, the college admitted three Japanese-American students who had left internment camps. Even more hazardous was the decision by the Board of Trustees, prodded by the president, to deny the request of a local defense plant, the Triplett Corporation, who wanted to use empty campus buildings for its work. The decision alienated a powerful local leader who had previously been a generous contributor to the college.(29)

Meanwhile, the college consciously strengthened its ties with the CPS system. Some of its grads rose to key positions in CPS. Roy Wenger of the class of 1932, for instance, helped to found the "smoke-jumpers" program, CO firefighters who parachuted into hot spots. Art professor Klassen toured the camps extensively, giving demonstrations in wood carving and ceramics, while education prof Jacob Schultz and sociologist Irvin Bauman taught a number of courses to conscientious objectors (COs) at the Ypsilanti, Michigan unit. Home Economic professor Edna Ramseyer helped to create a women's equivalent of CPS, the "CO Girls," and also taught dietetics in a CPS camp in Virginia and at MCC's relief training program in Goshen. The president himself visited COs in Florida, returning home from one trip with a chameleon which he had caught himself. He turned it over to biology professor M'Della Moon, who lodged it in a glass cage in Science Hall.(30)

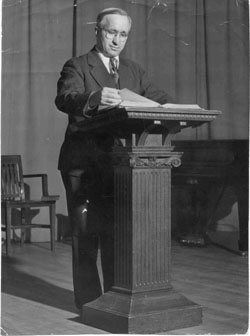

Lloyd Ramseyer, president of Bluffton College |

While remaining clear about his own pacifism, Ramseyer did his best to maintain cordial relationships with BC students who had entered military ranks. He readily wrote letters on behalf of their promotion to higher military rank, responding to the news of one that "it is always encouraging to hear of alumni who are making good." In return, numbers of such men sent small checks in support for the college, along with expressions of warmth for the president and for their alma mater. "My hat is off to you," Russell Fellers wrote Ramseyer, along with a ten dollar check, "because I think you are a man."(32)

Throughout the 1930s an increasing number of non-Mennonites had been coming to the college, and numbers of them wrote back to Ramseyer indicating that they had absorbed something of the college's mission, even as they bent themselves to the task of war. Former student Calvin Workman wrote Ramseyer from his air base in Virginia with sober thoughts about his job at hand. "The job I am preparing to do myself I do not believe in, so I can imagine how religious people would look upon it," he confessed. "Whenever you hear and read of the glory of the Air Corps, you can be assured that quite a number of those heroes (so called) flying in our bombers shall hate and be ashamed of that part of their lives, forever... I am just a small cog in the machinery that must deal out the destruction." Assigned to a bomber crew and stationed in England, Fellers penned Ramseyer between missions that "sometimes as I am flying over enemy territory and the flak is terrific and at the same time I'm trying to drop bombs, I think, 'how silly and childish the entire thing is.'" Ex-student Dale Francis said it more simply, telling the president that "next time I'll stand with the objectors."(33)

Such comments provide a telling indication of the kind of transformation in peace teaching that had swept through Bluffton and also, by extension, larger sections of the GC and MC Mennonite world in America in the first half of the twentieth century. To be sure, this transformation was best seen on the level of official church teaching. As Bluffton's and other Mennonite draft census numbers revealed, large numbers of lay Mennonites, young and old and in both groups, continued to decide on different courses in regards to war and peace than official church counsel preferred.(34) Nonetheless, the change in this official church teaching was still remarkable. In contrast to the ambiguity of Mennonite responses to World War I, to a great degree, the relative firmness of course illustrated by Lloyd Ramseyer twenty years later was indicative of the choices made by leaders across the church. There would be further adjustments to Mennonite peace theology in the latter half of the century, but by the end of World War II, at least, Mennonite leaders appeared to have mapped out some clear choices for the laity to accept or reject.

1. The most concise summary of the solidification of Mennonite peace teaching in the interwar era is Paul Toews, "The Long Weekend or the Short Week: Mennonite Peace Theology, 1925-1944," Mennonite Quarterly Review 60 (Jan., 1986): 38-57. Also see Toews, Mennonites in American Society, 1930-1970: Modernity and the Persistence of Religious Community (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1996), 107-128; and James Juhnke, Vision, Doctrine, War: Mennonite Identity and Organization in America, 1890-1930 (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1989), 294-299.

2. On the progressive orientation and agenda of the college leadership at Bluffton, see Perry Bush, Dancing with the Kobzar: Bluffton College and Mennonite Higher Education (Telford, Pa: Pandora Press, forthcoming, May, 2000), 59-69. Much of the following analysis is drawn directly from this text.

3. David Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (NY: Oxford University Press, 1980), 45-92;

4. Juhnke, Vision, Doctrine, War, 208-224; Gerlof Homan, American Mennonites and the Great War (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1994), 57-86.

5. Juhnke, Vision, Doctrine, War, 229-30, 234-40; Homan, American Mennonites and the Great War, 87-88, 99-128; James Juhnke, "Mennonites and Ambivalent Civil Religion in World War I," MQR 65 (April, 1991): 162.

6. Hirschy to Thierstein, Sept. 9, 1917, Hirschy Papers, I-A-a, Box 2, "photocopies of N.C. Hirschy," Bluffton College Archives (hereafter abbreviated BCA).

7. Langenwalter to Mosiman, April 20, 1918, Mosiman Papers, I-A-b, Box 8, "J. H. Langenwalter..." BCA.

8. Mosiman to Aaron Augsburger, May 14, 1918, Mosiman papers, Box 7, "Rev. Aaron Augsburger..." BCA; Homan, American Mennonites and the Great War, 71.

9. Mosiman to J. Bechtel, May 23, 1917, Mosiman Papers, I-A-b, Box 9, "Corresp., A.S. Bechtel, J. B. Bechtel..." BCA; Mosiman to P.H. Richert, March 23, 1918, Mosiman Papers, Box 12, "War Committee on Exemptions, 1917-19,"; Mosiman to V. Schlagel, Aug.10, 1918, Mosiman Papers, Box 11, "Mosiman personal corresp., 1913-31"; Mosiman to C.J. Claassen, Sept. 13, 1918, Mosiman Papers, Box 1, "Claassen corresp.," BCA.

10. Mosiman to Claassen, June 22, 1918, Mosiman Correspondence, I-A-B, Box 1, "Claassen Corr." BCA; Mosiman to Cox, April 11, 1917, Mosiman Papers, Box 4, "Mosiman letters to Governor," BCA.

11. Mosiman to William Clegg, Nov. 2, 1917, Mosiman Papers, Box 12, "War, 1917-19," BCA; Mosiman to V.C. Ramseyer, July 25, 1918, Mosiman Papers, Box 2, "Misc, Ramseyer, Rickert..." BCA; Mosiman to F. P. Keppel, Aug. 13, 1918, Peace Papers Collection, I-X-a, Box 1, "Corr. to people in the Army," BCA.

12. Mosiman to J. W. Kliewer, April 15 and June 28, 1918, Mosiman to Mussleman, Oct. 22, 1917, all in Mosiman Papers, Box 12, "War Committee on Exemptions, 1917-19," BCA; Homan, American Mennonites and the Great War, 132-3, 87, 91-2.

13. Mosiman to General Education Board, April 29, 1919, Mosiman Papers, I-A-b, Box 2, "Gen. Ed. Board," BCA; Kratz to Mosiman, May 31, 1918, Byers to Mosiman, May 3, 1919, both in Mosiman Papers, Box 2, "Faculty corresp.," BCA; Berky to Mosiman, Jan. 7, 1919 and Lehman to Mosiman, no date, both in Peace Papers Collection, I-X-a, Box 1, "Corr. to people in the Army," BCA.

14. WIT 6 (March 1, 1919): 1; WIT 5 (Oct. 27, 1917): 3; WIT 5 (May 4, 1918): 1; WIT 6 (Oct. 12, 1918): 1, 3; WIT 6 (Nov. 30, 1918): 1, 3; WIT 6 (March 29, 1919): 3.

15. 1918 Ista pp.183, 189; WIT 4 (May-June, 1917): 24-5; WIT 5 (Dec. 8, 1917): 2; WIT 5 (Nov. 10 and 17, 1917): 4; WIT 5 (May 18, 1918): 2; WIT 6 (March 29, 1919): 3.

16. Mosiman to William Harvey, Oct. 30, 1924, Peace Papers Collection, I-X-a, Box 1, "Peace, misc. materials," BCA; Mosiman, "The Limitless Christ," BCB IX (Oct., 1922): 1-8; C. H. Smith to Wilbur Thomas, Jan. 18, 1925," Mosiman Papers, I-A-b, Box 8, "American Friends Service Committee," BCA; Mosiman to Richard Lehman, June 25, 1919, Mosiman Papers, Box 5, "Rev. F. Richard Lehman..." BCA.

17. Toews, "Long Weekend or Short Week," 42-43; Albert N. Keim, Harold S. Bender, 1897-1962 (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1998), 61-2.

18. Perry Bush, Two Kingdoms, Two Loyalties: Mennonite Pacifism in Modern America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 41-43, 55; Toews, "Long Weekend or the Short Week," 40, 48-49, 55.

19. Ramseyer to Dale Francis, Sept. 21, 1941, Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 4, "Ramseyer Letters, 1929-42," BCA; Lloyd Ramseyer, "Looking Forward," Baccalaureate Sermon June 9, 1940, Ramseyer Baccalaureate Sermons, Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 13, BCA.

20. Ramseyer to Smucker, Oct. 3, 1940, Ramseyer papers, I-A-d, Box 4, "Letters, 1939-41," BCA; WIT 77 (March 15, 1940): 3.

21. Smucker to Ramseyer, August 22, 1941, Ramseyer Papers, Box 4, "Letters, 1939-42," BCA.

22. Ramseyer to Adam Amstutz, Dec. 9, 1941, Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 1, "Letters to Old Friendship Group, 1940-41," BCA; "Special Faculty Meeting" dated Jan. 14, 1942, I-E-a, Faculty Meetings Collection, Box 1, "Faculty Minutes Sept. 1935 -- May 19, 1944," BCA.

23. "Report of the Dean to the President and Board of Trustees," April 10, 1942, March 24, 1944 (Schultz quote), May 2, 1945, October 24, 1947, all in Board of Trustees Papers, I-B-a, No Box number, "Minutes of the Board, 1936-49," BCA; 1943 Ista, p. 60.

24. 1944 Ista, 42; S. F. Pannabecker, Faith in Ferment: A History of the Central District Conference (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1968), 234.

25. WIT 29 (Jan. 12, 1942): 2; WIT 29 (March 30, 1942): 3 and (Feb 23, 1942): 2.

26. Student Senate minutes dated Nov. 16, 1942, Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 10, no folder; 1943 Ista, 50; WIT 30 (Jan. 16, 1943): 1, and (April 19, 1943): 1942 Ista, 68.

27. Ramseyer to John McSweeney, Oct. 28, 1941, Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 4, "General, 1940-41," BCA; Ramseyer to "Whom it may concern," May 9, 1942, and to Robert Wagner, Dec. 2, 1942, both in Ramseyer papers, Box 9, "Letters, 1939-42," BCA; Ramseyer to M. Dillon, May 8, 1942, Ramseyer Papers, Box 4, "Letters, 1939-41," BCA; BCB 28 (Sept., 1941): 7.

28. Ramseyer to Henry Fast, Jan. 11, 1943, Ramseyer Papers, Box 6, "Corr., 1938-46," BCA.

29. On Japanese-American transfer students, see: undated memo in Ramseyer Papers, Box 1, "Publicity, 1942-3," BCA; Memo to Bluffton News October 6, 1942, Ramseyer Papers, Box 1, "Japanese Students, 1939-46," BCA; Ramseyer to William Ramseyer, Oct.1, 1942, Ramseyer Papers, Box 9, "Letters, 1939-42," BCA. On the Triplett refusal, see Ramseyer to Norman Triplett, Jan. 26, 1945, Ramseyer Papers, Box 6, "Corr., 1939-45," BCA.

30. Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace (Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee, 1949), 141, 147; Ernest Miller to Schultz, Nov. 1, 1944, and Ramseyer to Elmer Ediger, Sept. 17, 1943, both in Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 12, "CPS Camps," BCA; Members of the Faculty, Bluffton College: An Adventure in Faith (Berne, Indiana: Berne Witness Press, 1950), 190-91; Bush, Two Kingdoms, Two Loyalties, 111-2; Ramseyer to Edmund Zehr, Ramseyer Papers, Box 6, "Corr., 1938-49," BCA.

31. Ramseyer to Ellwyn Hartzler, Jan. 24, 1945, Ramseyer Papers, Box 6, "Corr., 1944-47," BCA; Ramseyer, "Lift up Your Eyes," p. 1-2, Baccalaureate Addresses, Ramseyer Papers, I-A-d, Box 13, "Ramseyer bacc. sermons," BCA.

32. See Ramseyer letters of recommendation for Mark Houshower, Ramseyer Papers, Box 11, "Kaufman, Edmund G," BCA; for Richard Backensto, Feb. 2, 1942, Box 4, "Letters, 1938-42"; Ramseyer to Myron Brown, Jan. 7, 1943, same file; Fellers to Ramseyer, June 28, 1944, Ramseyer Papers, Box 6, "Corr., 1938-42," BCA.

33. Calvin Workman to Ramseyer, Jan. 20, 1944, Dale Francis to Ramseyer, May 3, 1944, all in Ramseyer Papers, Box 6, "Corr., 1938-42," BCA.

34. See Bush, Two Kingdoms, Two Loyalties, 80-89, 97-105.