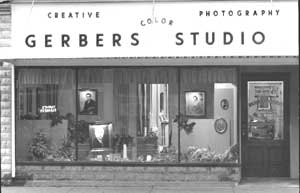

Gerber Studio in Bluffton.

Photo by Leland Gerber.

Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College.

June 2000

vol. 55 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

June 2000

vol. 55 no. 2

Back to Table of Contents

| ". . . the places we have roots in, and the flavour of their light and sound and feel when things are right in those places, are the wellsprings of our serenity."(1) |

A Place in Bluffton

When our family went home to spend Christmas with my parents in Bluffton, Ohio, about ten years ago--sometime in the midst of the household warm with the smell of spices and the activity of seven grandchildren, perhaps it was when my brother, my sister and I were washing dishes after a meal--my mother said,

"Did you hear? The studio burned."

Gerber Studio in Bluffton. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. |

The studio. My father, retired for more than six years already, had been a professional photographer in Bluffton for 30 years. The building that burned housed Gerber's Studio most of my growing up years. Several years before this Christmas conversation took place, glad to be relieved of the maintenance responsibility, my parents sold the old building to a new photographer in town, who had bought dad's business at his retirement.

"Oh," I said in response to my mother.

"Yes," she went on. "The fire caused a lot of smoke damage in the discount store next door. They had to close down for almost a week and it was just before Christmas which is one of their busiest times and they lost a lot of business."

And then I saw my mother was crying. Crying? Because the studio burned.

So it burned, I caught myself mentally shrugging. It was an old, empty building, an ugly building, a dead building. The man who bought the studio, to whom dad virtually gave the business because he wanted to help someone get started and keep the small business and its service to the community alive, never really had his heart in it.

"One way to kill a business is to keep irregular hours," my Dad would occasionally observe sorrowfully as he watched the studio in different hands.

"We had all Dad's old pictures out at least," Mom interrupted my thoughts. "The man who owned the studio after Dad carpeted the lineoleum floors and after he left it was a dance studio--some days of the week, or evenings. It's all boarded up but if you drive by you can still see the sign dad made. . . . " Her voice trailed off. I looked at her; she looked smaller to me than I had remembered. And older.

And then because Peter was clamoring to be picked up and Rachel and Mara needed help finding somewhere to put puzzles together and because I felt no grief at the burning of the studio, I turned away from my mother's tears, as careless children sometimes do, and busied myself elsewhere.

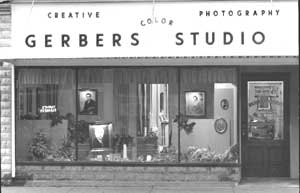

The "Golden Spike Limited" excursion passenger train passing through Bluffton in May 1969, with a locomotive built in nearby Lima--a place of community memories passing away. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. See Bluffton News, May 22, 1969. |

Roots of Placelessness

Many of us who are shaped by North American culture tend to ignore, dismiss, mistrust or trivialize the significance of place. Placelessness characterizes modern people in general, geographer Edward Relph writes. Placelessness "describes both an environment without significant places and the underlying attitude which does not acknowledge significance in places."(2)

What are the roots of this attitude toward the significance of place?

Increased geographical mobility. Some suggest that a marked increase in geographical mobility among Americans--following jobs or educational opportunities--can lead to poverty of place. During the first 18 years of our marriage, for example, my husband, Ted, and I lived in 13 different homes. My mother lived in one until she moved to Bluffton at her marriage 45 years before the studio burned. My parents had been in the same home in Bluffton ever since.

Mobility is not a new phenomenon--the Pilgrims moved to Plymouth, my Swiss ancestors moved to Ohio and Indiana, and many Chinese to California--but the increased scale of mobility given ease of transportation is striking.(3)

Mobility is not always by choice of course. There are those who lose place because of their lack of power and control. There are the farmers whose land is submerged for reservoirs, the native Americans driven out by soldiers, political refugees, those dislocated by war, street children, the poor. In losing place they may refuse, fear or find it difficult to become attached to new places--or they may have no place they can call their own.

American individualism. It's not just moving that leaves place "storyless" and that makes commitment to people over time difficult. Others point to a deep-seated American spirit of individualism which has made a virtue of leaving home and which has little use for the past. Scott Russell Sanders chides us that

|

From the beginning, our heroes have been sailors, explorers, cowboys, prospectors, speculators, backwoods ramblers, rainbow-chasers, vagabonds of every stripe. Our Promised Land has always been over the next ridge or at the end of the trail, never under our feet. One hundred years after the official closing of the frontier, we have still not shaken off the romance of unlimited space. If we fish out a stream or wear out a field, or if the smoke from a neighbor's chimney begins to crowd the sky, why, off we go to a new stream, a fresh field, a clean sky. In our national mythology, the worst fate is to be trapped on a farm, in a village, in the sticks, in some dead-end job or unglamorous marriage or played-out game. Stand still, we are warned, and you die.(4) |

Self-reliance, a pioneer virtue, orients itself more in terms of growth toward independence, ease of adjustment to change and future fulfillment than to growth toward long-term mutual dependence and commitment in the context of traditional communities. For Europeans leaving places where tradition and topographical constraints bound them to limited station in life, American space symbolized hope and achievement. "Mobility is always a weapon of the underdog," Harvey Cox points out.(5)

Individual freedom taken to an extreme, however, sacrifices depth and community and the significance of place. David Fopher reflected this spirit when he scoffed, "To be rooted is a property of vegetables." (6) Place requires accepting certain limitations and obligations.

North American Mennonites have not been untouched by the cultural values of independence, freedom and individualism.

Environmental placelessness. Edward Relph laments what he calls an increasingly "placeless geography," or an environment without significant places. Our current scale of destruction of distinctive places leaves behind "a labyrinth of endless similarities."(7) In my brief lifetime I have seen the American landscape change with the growth of the highway system. Efficient but nondistinct fast-food stores, hotels, and entertainment centers seem to pop up like mushrooms. Stephen Kurtz, reflecting on the experience of eating in Howard Johnson's restaurants, remarked that "Nothing calls attention to itself; it is all remarkably unremarkable . . . . You have seen it, heard it, experienced it all before, and yet . . . you have seen and experienced nothing."(8) When we travel around America Mennonites can almost always feel at home because we can almost always find a McDonald's nearby. But the price of this familiarity is environmental sameness.

The erosion of environmental places is not limited to America, however, and is exacerbated by global telecommunications. I remember hearing from a Mennonite volunteer working in the Philippines about his intense anticipation of visiting one of the tribal groups in the highlands of Luzon for the first time, looking forward to getting a flavor of life in a traditional village. When he arrived he found many of them sitting around their community TV watching the video "Witness," an action movie where an Amish community in Pennsylvania becomes a place of refuge and a final shoot-out.

We have barely explored the implications of television or e-mail for our sense of place. Edward Casey suggests they create "virtual place" where even though people are not physically present together they share the same "coziness and discreteness" which marks place. It is not clear whether "virtual place" will further contribute to the erosion of identity and community associated with "placelessness," or rather provide a vital new form of place.

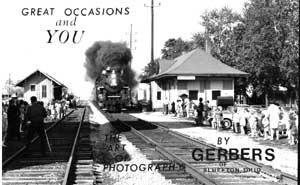

Gerber Studio advertisement. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. |

Definition and Characteristics of Place

Places have location; that is fundamental. Place is localized space. Whenever we think of particular units of space such as cities or districts or provinces, or a specific part of space, like a college campus or a church building, we recognize that place in contrast to space is always "immediate, concrete, particular, bounded, finite, unique."(9) A place is characterized by its locale and interconnected with surrounding places.(10)

But places are not just localized spaces on earth. Place is expressive space, meaningful space. If space is "geography viewed from a distance . . . calmly waiting to have meaning assigned to it,"(11) then place is geography close at hand, space filled with significance. Kent Ryden in Mapping the Invisible Landscape suggests that for those who have developed a sense of place, "it is as though there is an unseen layer of usage, memory and significance--an invisible landscape, if you will, of imaginative landmarks--superimposed upon the geographical surface and the two-dimensional map.(12)

Place is also interactive space. Every place is a "unity of experience," of people, memories, plants, bacteria and other hidden forces "dwelling together."(13) To speak of "place" in this way is to conceive of it not just as a location or background for something else. It is to speak of place as a complex interaction of our bodies, the natural world, physical objects, feelings, memories, history, social relations, cultural and religious systems of meaning. As such place is "equal parts geography and imagination," a complex intermingling of mind and landscape, "so that neither is finally separable or meaningful without the other."(14) "Places are thus incorporated into the intentional structures of all human consciousness and experience."(15)

Ryden also underlines the power of place as symbol. While artifacts, objects or actions in a place may distill and carry its symbolic meaning, the place itself may also gather up various dimensions of its life and accrue symbolic meaning, integrating the visible and invisible geography of the place.(16) If place is deeply absorbed, "the actual physical place may drown or be blown up, but the layers of the sense of place remain, like stacks of valuable china on a table after the magician has whisked the tablecloth away." A sense of place can therefore sustain identity, provide connections to a personal and collective past, offering an emotional center. "It is a rooted and anchored locus of meaning and value."(17)

With this orientation toward place we can delineate various dimensions of place.

Place is sensible. It has a physical dimension. Through our senses we are literally in touch with our environments, we feel the world in our flesh and bones. Our whole selves are involved. We detect line, shape, slope, quality of light, color, texture, air movement, aroma, sound, substance and consistency, temperature, overall form and design. We interpret data and its meaning. Sometimes we "read" the physical place instinctively, unselfconsciously, sharing with other animals a biologically rooted attachment to place.(18) Over time a unique blend of the physical geography of a place, Tuan suggests, "is registered in one's muscles and bones."(19)

First Mennonite Church in Bluffton, 1950s, sacred space enclosed by rounded arches, curved benches, and center pulpit. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. |

Place evokes feelings. A place is not only seen, heard and smelled, but it is "loved, hated, feared, revered, enjoyed, or avoided."(20) Alan Gussow refers to a place as "a piece of the whole environment that has been claimed by feelings."(21)

The "mood" of a place is related to the life situations it evokes for us. (Hospital as a place to get well or a place to die.) Through life experience space is differentiated into various meaningful centers. In this respect the emotional meaning of a place is essentially individual. One can conceive in this way of the entire earth as "an immense patchwork of miniature . . . private geographies of individuals."(22) Within shared space, such as a college campus, for example, "each person's sense of place is altered to fit his or her personal experiences within those larger patterns: like jazz soloists, individuals create unique styles and interpretations of life while remaining within the rhythms and structures of a larger composition."(23) Since we each bring a different mix of personalities, memories, and feelings to a place, we are committed with different degress and intensities to a place.

Not surprisingly our feelings about place are often the strongest in relation to those places where we have spent the most time or "where the quality and intensity of experience is greatest."(24) Unhappy or fearful experiences and peak experiences connected with "joy, ecstasy, awe, despair, unity with our surroundings" or making commitments are often bound in our memory to place.(25) Moral categories and morale help to define the emotional quality of a place: "A place is good or bad, blessed or damned, happy or unhappy, lively or depressed, exciting or dull."(26) We also choose to see what we want to see and "blank out the ugly, boring, offensive, familiar and unchanging."(27)

While individuals are the ones who attach emotional meaning to a place, the subjective experience is not detached from the place. "The feelings of a place . . . come from collective experience and they do not happen anywhere else. They belong to the place."(28)

Place integrates nature and culture. Culture--a common web of meaning--helps to define and interpret a physical space. From this perpective the meaning of a place is "intersubjective since a cultural group is socialized according to a common set of experiences, signs and symbols." A cultural insider can participate unreflectively in the symbols of a place; an outsider needs to try to grasp deliberately what the places mean for those who dwell in them.(29)

Europeans and aboriginals view the landscape of Australia quite differently, for example. Where Europeans see "uniformity and featurelessness," aboriginals see significant details and a powerful invisible landscape. "Every tree, every stain, hole, and fissure has meaning."(30)

Cultural symbols--whether material, ritual or verbal--point beyond themselves and open up levels of reality which are otherwise closed. They are not simply and intentionally produced, but they grow and die. Edward Relph notes that traditional landscapes were full of symbols. Buildings, landforms, city plans often had sacred meaning. He points out the more contrived signs of our current American landscape: TRUCK STOP WOMEN X, signifying permissiveness and exploitation or SKI COLORADO, signifying individual freedom and material comfort.(31)

To understand the cultural meanings of a place takes time. Learning the appropriate patterns of politeness, for example, may not be easy for an outsider entering a new place. Barbara Johnstone, in a study of middle class Indiana culture, said politeness takes two forms. If a culture practices intimacy or "positive politeness" they are explicit in showing care for others and identifying with them. If they practice independence or "negative politeness" they treat people as independent agents who should not be imposed upon unduly. Each form has a set of rules. Negative politeness, for example, means being relatively reserved, rarely talking to strangers, talking in subdued voices in public places, and keeping feelings about the community to themselves, assuming outsiders wouldn't be interested. This style also affects how people converse: listener participation is minimal, there is deference to a speaker's right to the floor, there is overt tolerance even for poor speakers, and comments are made only after the speaker is through. Disapproval is expressed by change of subject rather than directly.(32)

Belonging to a place, being "inside" it, requires not only physical presence and emotional connection but the ability to sense the cultural meaning of a place without deliberate and self-conscious reflection.

Place is storied space. Place is bound up with time and memory. As a result of our experiences in a place "a thick layer of history, memory, association and attachment" builds up in a location. History becomes "fused to location;" "place is time made visible." Thus places evoke stories, and through narratives, both personal and communal, meanings that permeate the place are "given form, perpetuated and shared."(33)

Stories also help create a place. They nurture a sense of belonging, show how power relationships ought to be played out, mediate between personal experience and shared social norms. They may perpetuate the status quo or assist social change.(34) Personal experience stories provide glimpses of the emotional interpretation people put on the places around them, revealing the "place-anchored emotions" common to a group of local residents.(35)

Time, narrative and identity are closely linked with place. Ryden writes that "a concern with time brings a sense of past narratives; a concern with identity brings a sense of the narratives which run through one's life. Both concerns are required to bring to light all the stories which comprise a place, and both make place valuable, keeping the past close at hand . . . and keeping identity firmly grounded." (36)

Narrative further structures our sense of self and interactions with others in particular places. We are at home in place when the place evokes stories. "Community stories serve the same sort of function as geography talk, in a less explicit way." They create a sense of belonging by evoking the collective memory that defines a group. "Individuals' relationships to groups are mediated through shared memories, memories organized around places and the stories that belong to places."(37) People who share stories also share places.

Place is a point in a network of social relations. In contrast to the angle of vision assumed in viewing place as "storied space," which closely links time and place, this angle of vision focuses on place as a particular "meetingplace" in a network of larger social relations and understandings. I am indebted to social geographer Doreen Massey for this picture of space as "social relations 'stretched out'". From this perspective places are not so much "bounded areas as open and porous networks of social relations." For example, a liberal arts college as a point in a network of social relations is a meetingplace for faculty, staff, students, alumni, for people of different nationalities and cultures, for people from different economic classses, different age groups, different genders, from different religious denominations. It is a particular, unique point of intersection. By speaking of the network as "open and porous" Massey seeks to emphasize that the social identity of a place is not understood simply by describing the social interactions internal to a place but is also formed by specific interactions with other places. In this perspective it is important to think of the way in which the college relates to the surrounding community or to a neighboring university as part of its identity, rather than thinking of the college as "not being the other place."(38)

The geography of social relations forces us to recognize our interconnections, not simply those we readily identify because they are located in the same region--like the relation of a college to a neighboring school--but also the relations which lie beyond them--the people who grow coffee for the school cafeteria or sew clothes for the students and faculty, the alumni giving political or educational leadership in other countries. Places, as Relph puts it, are "part of a framework of circulation." "The global is in the local in the very process of the formation of the local."(39)

Because it is created out of social relations, "space is by its very nature full of power and symbolism, a complex web of relations of domination and subordination, of solidarity and co-operation." Massey notes that "the particular constellation of social relations which are woven together in a particular location form its "geography of power relations." Globalization and time-space compression means not just sped up, instantaneous communication but the "spatial reorganization of social relations, where those social relations are full of power and meaning."(40)

Because places are shared spaces they are characterized by conflict--between, for example, "views of what the area is, and what it ought to become." One can speak for example of a place as a "counterposition of one identity against an other." What will be the dominant identity of a place is "the result of social negotiation and conflict."(41) Indeed, not only the social but the very physical geography of the place reflects the influence of the powerful.

Place is dynamic space. While at first glance, like my initial glance at the old studio, place may seem to be something static, a unique location but "just a place," a richer understanding of place sees its dynamism. Not only may the various dimensions of place describe change over time--physical elements, emotional meaning, cultural significance, the addition of further layers of history, its geography of power--but the various dimensions of place themselves interact with each other in a dynamic way. Place is not just background for a deposit of sentimental feelings but a dynamic intersection of both the visible and invisible terrain.

Relph suggests that "an authentic sense of place is above all that of being inside and belonging to your place both as an individual and as a member of a community, and to know this without reflecting upon it."(42) Ryden believes that it is the layer of emotion that "probably contributes most to separating the perspective of the insider from that of the outsider."(43) How we feel about a place--how we feel about where we fit in its social geography, how we feel about our relationship to its cultural geography, how we feel about its physical geography, how we feel about the identity revealed through its narrative geography--draw us inside a place or leave us on the margins.

Russell Suter farm near Bluffton. The old stone quarry on Riley Creek, a place flooded with its own spirit. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. |

The spirit of a place. An understanding of place which recognizes its expressive meaning can speak about "the spirit of a place." Different places have different "feelings," explains E.V. Walter, based in the everyday sensory, moral and emotional experiences one has in the place. The "feeling" of the place has to do with the structure of morale, the expressive energies, the passions and myths involved, the biographies and local histories, the drama of living or working together there." (44) The spirit of a place emerges from the unique content and patterns of its physical features, the events which take place within its social and cultural landscapes, its stories and symbols. Just as a person's "character" or "personality" endures over time, so the spirit or character of a place endures. But to interpret and speak of the spirit of a place is difficult. A geographer stumbles like a poet to find concrete images which can express the quality of a particular place: a haven, a bull-pit, a saccarine-spirited social club.(45)

Walter proposes that places even have energy. "Something has energy if it causes changes in experience--if it makes people think, feel, or act, . . . or stimulates the imagination." It is possible therefore to talk about the "educational energy" or the "religious energy" of a place.(46)

Aerial view of Bluffton. Homes, churches, and a college--places of institutional energy. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. |

A Mennonite geography of the spirit

As a Mennonite theologian listening to geographers and philosophers and folklorists converse about place, I found myself reframing and furthering their questions. Is there such a thing as "a sense of place with God?" What might we mean by this? Is there such a thing as Christian "placelessness"? Is this good or bad? What is there about certain places--for example, church buildings, homes, and bodies--that make them "places with God"? What might we learn as Mennonites that might press us to modify our practice of faith in these places?

Place with God. Given the fuller understanding of place outlined above and my Mennonite Christian perspective, what do I mean by "place with God"?

Initially and obviously, in addition to the dimensions of place, noted above, place with God has a religious dimension. A religious system of meaning will interact with each of the dimensions of place: physical, emotional, cultural, social, historical.

In studying religions it is common for scholars to identify and describe sacred spaces important in religious traditions. Sacred space identifies locations where adherents have met the divine or continue to go to encounter divine power. Sacred space is where divinity dwells or draws near or where holy power is released. Sacred space is set apart by thresholds and doors and boundaries, and is filled with religious meaning represented in symbols, sacred centers, objects. The sacramental mediation of grace as understood and practiced in the mass of the medieval Roman church participated in such an understanding of sacred space.

Zwingli and most of the Anabaptists challenged the Roman church's definition of the sacramental mediation of grace. Many of the Anabaptists believed that Christ was physically present on earth, but not in the bread and wine. Rather Christ was present in the true church which would make visible the mind and spirit of Christ by conforming to his life.(47) This, too, is a sacramental view, but it locates "sacred space" not in buildings or objects, but in the gathered saints, the Body of Christ on earth.

The notion "place with God" is yet another way to look at sacred space. Place is dynamic meaning-filled geographical space. Place with God is a dynamic place filled with theistic religious meaning. Christian place with God is a dynamic place filled with Christian meaning.

Because this way of putting it does not emphasize the active character of the Holy Spirit in creating Christian meaning or the crucial participation of God in making "place with God" I am proposing a further component to the definition: Christian place with God is a dynamic space filled with Christian meaning and a place where the Spirit of Christ dwells. While we usually see ourselves as individuals or communities managing or controlling "places," given the character of place described above, we might redescribe ourselves. Even from a secular perspective we do not manage, though we contribute to, the complex and intricate mix of the material world, the meanings and interactions that constitute place. In religious perspective we speak of the mysterious mix which generates a significant sense of "place with God" out of the ordinary elements of place, as the Spirit of God at work in that place. We participate with God in creating "place with God." (48)

There is a further implication of this way of looking at sacred space. Since place with God is relational, specific spaces must be able to host both God and humans. Since there is no place on earth that God cannot be, any place on earth where humans can physically be together with God can potentially become a place with God, in that sense a "sacred place"--a dynamic place filled with Christian meaning and a place where the Spirit of Christ lives. There are no intrinsically sacred places and there are no places which are excluded from becoming sacred, that is, the Spirit of God is not limited by institutional forms or practices or priests.

Admittedly there are some places are so filled with blood and hostility that we can feel only evil in the spirit of the place. Even so, and perhaps precisely in such cases, a Mennonite perspective on place with God, reminds us of the call of Jesus to take up the cross and follow him. For it is in making ourselves vulnerable to the Spirit of Christ that God continues to use us in such places to "re-place" the geography of violence with the geography of faith, hope, and love.

Like other places, Christian place with God is sensible, sensual and located. It has a physical dimension. Speaking of "place with God" recognizes that our experience of God is embedded in place.(49) God comes to us not abstractly but "emplaced." In other words, though God is not sensible, place with God is. In the midst of the natural and material world, utilizing our senses, we encounter God. Therefore referring to "a sense of place with God" always involves some measure of particular localized description. "It was in that field on an Alice Chalmers tractor that I promised God. . . ." "When I first held my daughter in that hospital in the Congo all I could do was thank God she was alive." Paraphrasing Sanders, the geography of land and the geography of spirit are "one terrain." (50)

Indeed by naming a sense of a "place with God" a Christian not only recognizes that she stands in a divine-human relationship there but that she is also connected to the rest of what belongs to God there. Place recalls our relation to physical being and to nonhuman creation as well as to the neighbors we encounter in that place.(51) A sense of "place with God" therefore has ecological implications as well.

Place with God evokes feelings. It marks a place where our feelings about the place are bound up with our feelings about God. While there may be elements of drudgery, desire to escape, and even misery in the mix of feelings that accompany a place with God, there is a deep sense of belonging.

Place with God is a dynamic space where nature and culture meet. It is a place where available cultural categories, meanings and values are often assumed, sometimes consciously adopted and adapted, and sometimes rejected. From the language that is spoken to the sense of time assumed, the culture or cultures in which we stand shape the places where the Spirit of God meets us. But places with God are also marked by a specific kind of religious energy: the Spirit actively challenges those cultural values which contradict the way of Christ, making "place with God" a dynamic, tensive space, and creating change.

Place with God involves a porous network of social relations. Christian "place with God" includes a sense of belonging to God and to a community that is both localizable and global. "Place" therefore entails relationship and commitment. As Walter Brueggeman wrote, "Place is [indeed] a protest against the [unpromising] pursuit of space. It is a declaration that our humanness cannot be found in escape, detachment, absence of commitment, and undefined freedom." Place is relational. Place with God is a place where the Spirit is moving the network of social relations toward greater justice and love. It is place where connections to the larger church are remembered, valued and nurtured. It is a place where the geography of power in the place is examined in light of the geography of power reflected through Christ, and where tensive conflict and peaceful negotiation are assumed to be creative elements of a dynamic space.

Place with God is storied space. A place with God gathers meaning over time. It helps us recall and tell stories about how we and others have met God, listened for and responded to God's Spirit or perhaps failed to do so. It is a place that recalls our common history as Christians, or reverberates with the biblical narrative. It is a place where one story elicits another: stories of acceptance and redemption, courage and failure and renewal, stories of care for God's earth, for the excluded, the poor, stories of love for enemies and transformation of spirit, stories of suffering and loss endured for love of God, stories of pain and the recovery of meaning, of healing and death with God.

We might also speak of the spirit of a place with God wherever its location--a home, a cemetery, a Christian school, a church. Whatever specific images are chosen to paint the spirit of a particular place, if it is truly a place with God, fruits of the Spirit of Christ (love, joy, peace, patience, kindness) will mark (not its life at every moment) but its enduring character.

A Mennonite theological compass. It has been evident throughout my entire discussion of "place with God" that exploring this theme in a Christian perspective involves a normative as well as a descriptive component. How we interpret a sense of the presence of the "Spirit of God revealed in Christ" (our spirituality and theology) makes the difference in how we define "place with God" and whether and how we encounter God in Christ in particular places.

Our theology functions the moment any of us begins to form words about God. What we see in the power geography of a "network of social relations" and what transformations we recommend, for example, involve understandings drawn from Christian vision and practice.

My theological "compass" for thinking about place is a strong pneumatology tempered by respect for Scripture and for the counsel and admonition of other believers in interpreting the voice of God in particular situations. At the heart of original Anabaptist movement was a strong pneumatology or understanding of the Holy Spirit. The early Anabaptists appealed to the authority of the Holy Spirit in criticizing the church (to defend their antisacramentalism and anticlericalism) and in claiming the power to interpret Scripture, preach, reform the sacraments and revise the community of faith. Although in the developing Mennonite tradition this strong appeal to the Spirit was fairly quickly and dramatically moderated by acceptance of the authority of the church (the recognized leaders in it) and of Scripture (a fairly literal interpretation), the pneumatological roots continued to reassert themselves. Mennonites in practice continued to recognize the power of the Holy Spirit calling individuals to faith and to baptism in community (and to schism), of the Spirit helping people interpret Scripture in relation to new questions, and of the Spirit reforming and transforming communities of faith. In the latter half of this century, I believe there has been a significant increase in the appeal to the authority of the Spirit (and significantly reduced appeal to Scripture and the authority of the church) among North American Mennonites.

Acceptance of the reality and authority of the Spirit opens the way for movement, transformation, change in how we think "normatively"about church buildings, homes, and bodies in particular times and places. This is good. At the same time, our history demonstrates also the excesses and distortions that occur when people appeal strongly to their individual sense of what God desires or Scripture teaches. In thinking about what is the Christian meaning or significance of specific "places with God, " an orientation which values a "strong pneumatology tempered by respect for Scripture and for the counsel and admonition of other believers in interpreting the voice of God in particular situations,"calls for a conversational process, rather than an individual one.

In thinking about Christian responsibility in relation to such "places with God," this orientation suggests an approach to practical ethical decision making on matters of common import which involves deliberate conversation or "meeting in the power of the Spirit." (What kind of building should we have? How private should our home be? How do we care for our parents aging bodies?) This theological orientation does not turn for guidance to Mennonite history as such, or to the letter of Scripture as such, or to the authority of pastors or church leaders as such, but to a participatory decision-making process among believers "in the power of the Spirit." Such "meeting" may take different forms depending on circumstances--small groups or congregational meetings--and might use different decision-making styles--discerning conversation followed by individual decision, group consensus or voting. But the purpose of the meeting is to move towards a practical decision regarding meetinghouses or homes or bodies which weighs values, virtues and principles at stake at a specific time and in a specific place with openness to the movement of the Spirit of Christ present in the Body of Christ in the process.

Though the configurations of groups and the style of decision making may vary, attentiveness to the overall procedure is important in remaining open to the movement of the Holy Spirit: time for prayer and self-examination before God; making sure all have voice especially those regularly marginalized; fairness in speaking; deep listening to how others interpret Scripture relevant to the situation and how they see the Spirit of Christ nudging them or the group; securing leadership who will attend to these elements (not only to the specific method which has been adopted for final decision making), and who can help the congregation understand and respond appropriately to conflict.

With this theological "compass" at hand, it is possible to explore further the "geographical territory of the Spirit" linked to meeting places, homes and bodies. I believe it can be valuable for Protestant Christians and perhaps especially for those of us who stand in the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition to attend to our sense of "place with God." Insofar as we have failed to attend to the way place accrues meaning, insofar as we have underestimated "place with God" as a matrix of energies through which the Holy Spirit moves to renew, encourage and transform us, we have perhaps as Theodore Roethke wrote, "failed to live up to our geography."(52)

My overall desire in this project is to contribute in some small way to the continuing renewal or regeneration of the Mennonite church. In particular I hope to encourage greater consistency between our inner lives with Christ and our outward expression of faith in the way we make space for "place with God" with respect to our church buildings, homes, and bodies.

Gerber Studio interior. Photo by Leland Gerber. Credit: Mennonite Historical Library, Bluffton College. |

1 David Brower quoted in Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness (London: Pion, 1976), p. 146.

2 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 143.

3 Doreen Massey, Space, Place, and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), p. 150, reminds us that our comments about mobility need to be "socially differentiated." The degree to which we have mobility is affected by gender, race and class. For example, she describes the poor in Rio who know global football inside and out, have contributed to global music and dance and who have hardly ever been to downtown Rio are "imprisoned in time-space compression."

4 Scott Russell Sanders, Staying Put: Making a Home in a Restless World (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993), pp. 104-05.

5 Cox quoted by Deborah Tall, From Where We Stand (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), p. 96.

6 Fopher quoted in Tall, From Where We Stand, p. 97.

7 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 141.

8 Stephen Kurtz quoted in Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 143.

9 E.V. Walter, Placeways: A Theory of the Human Environment. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), p. 142.

10 To understand a place you need to locate it not in islolation from but in relationship to its larger ecology of place: Bethel College in Newton in Kansas in the mid-West in the U.S. in North America on the earth in this solar system in the universe.

11 Kent C. Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape: Folklore, Writing and the Sense of Place (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993), p. 37.

12 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 40

14 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 254.

15 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 42.

16 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 56.

17 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 95.

18 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 9.

19 Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), pp. 183-84.

21 Alan Gussow quoted in Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 142.

22 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 36 citing Annals (Association of American Geographers) 37, 1947, pp. 3-4. Relph also notes Teilhard de Chardin's good-humored complaint, The Phenomenon of Man (London: Collins,1955), p. 6 and 12: "It is tiresome and even humbling for the observer to carry with him everywhere the centre of the landscape he is crossing." And it is not just that he is in the center of his own space but that he recognizes that everyone else has their center too.

23 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 198.

24 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 33.

25 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 123.

27 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 123.

29 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 12 and 142.

30 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 15.

31 Relph, Place and Placelessness, 138-39.

32 Barbara Johnstone, Stories, Community, and Place: Narratives from Middle America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), p. 106.

33 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 255, 38 and 45.

34 Johnstone, Stories, Community, and Place develops these themes with extensive examples. She also explicates further the relationship between personal stories and social norms. "Stories of personal experience are stories of social experience. People tell about socially situated events; they tell stories in social interaction; and their stories are built around socially sanctioned plots and points and structured in conventional ways. Stories mediate between individual personal experience and shared social norms," p. 129.

35 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 86.

36 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 255.

37 Johnstone, Stories, Community, and Place, p. 5 and p. 121.

38Massey, Space, Place, and Gender, p. 2, 154, 121.

39 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 3. Massey, Space, Place and Gender, p. 120.

40 Massey, p. 265, p. 22, p. 121. Massey sets her views in the context of two significant developments in geography in the 1980s. "The massive spatial restructuring of economic and social spaces in the 1980's showed that geography matters; the aphorism of the 1970's was that space is socially constructed. In the 1980's the other side of the coin was added: the social is spatially constructed too, and that makes a difference. Society is necessarily constructed spatially. Space is therefore involved in the production of history and therefore in politics." Space, Place and Gender, p. 254.

41 Massey, Space, Place and Gender, p. 137, p. 7, p. 141.

42 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 65.

43 Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape, p. 67.

44 Walter, Placeways, p. 9, calls these qualities "expressive space."

45 Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 48, 56 and Walter, Placeways, pp. 9, 28, 142-44 seek to to define the spirit or soul of a place.

46 Walter, Placeways, pp. 127-128.

47 C. Arnold Snyder, Snyder, Anabaptist History and Theology: An Introduction (Kitchener, Ontario: Pandora Press, 1995), p. 355.

48 Is a sense of place something we create or a response to elements already there? See John Brinckerhoff Jackson, A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), p. 151. "It is my own belief that a sense of place is something that we ourselves create in the course of time. It is the result of habit or custom." He says others disagree, that sense of place comes from response to features already there. In Christian theological perspective I suggest we don't just "create" or "control" place with God; we cooperate with or host the transforming Spirit of God. Also see Walter, Placeways, p. 131: "A place is a matrix of energies, generating representations and causing changes in awareness."

49 "We do not have events and actions without the context of certain places. Places are thus incorporated into the intentional structures of all human consciousness and experience." Relph, Place and Placelessness, p. 42.

50 Sanders, Staying Put, p. xvi.

51 Walter Brueggeman, The Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1977), p. 5.

52 Roethke quoted by Scott Sanders, Staying Put, unumbered page before p. 1.