Keeping Faith and Keeping Time: Old Testament Images

on Mennonite Clocks

Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen

Ecce nunc tempus acceptum, ecce nunc dies salutis

(Behold, now is the accepted time, behold, now is the day of

salvation)(1)

This paper explores the Mennonite perception of time in the late 18th and 19th centuries through an analysis of painted clock faces manufactured by Mennonite clock makers in West Prussia and the Ukraine and used in Mennonite homes. This work will contribute to studies in didactic applications of biblical iconography on time pieces and is a first investigation of attitudes toward time - material culture being the primary source material - among Anabaptist/Mennonites who originated in the radical Reformation.

It will be seen that the Mennonite notion of time in relationship to faith is primarily stewardship of time, since time is understood as a gift of God and is the arena in which the kingdom of God must be made manifest through practical application of Christ's teaching.

When clocks are no longer decorated with biblical imagery by the later part of the 19th century, they are often paired with religious mottos both in the home and in meeting houses, and assume an iconic presence.

I will first discuss two clocks bearing Old Testament visual narratives, and then I will explore how these biblical themes are represented in a broader historical context in the visual arts in order to understand the relevance of these - today relatively obscure - biblical references to the people who made and used these clocks. Secondly I will consider Anabaptist/Mennonite textual sources in terms of attitudes towards time in relation to faith so that conclusions drawn from material culture analysis are balanced with an analysis of notions of time expressed in Anabaptist/Mennonite religious texts.

Of the household pendulum clocks manufactured by Mennonite clock makers - which have a long tradition in Northern and Central Europe - a small number feature biblical narratives. One of these is the story of Jephtha being greeted by his daughter upon his return home after defeating the Ammonites (Judges 11:29-40). (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1: King Hezekiah receives Assyrian messengers and prophecy of Isaiah; pendulum clock, Vistula Delta, ca. 1800, by Johann Kroeger? Private collection. Photo: Mark Wiens |

|

The other narrative is the story of Hezekiah as he receives the messengers of the Assyrian King (2 Kings 19 and 20). (Fig. 2) In the absence of sources that tell us what these images meant for their users, texts from the same period, such as Mennonite hymnbooks, catechisms, memoirs, as well as the writings of Menno Simons serve to reconstruct the significance of these visual motifs.

Fig 2: Jeptha greeted by his daughter; pendulum clock, Vistula Delta, ca. 1800, by Johann Kroeger? Private collection. Photo: Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen |

|

The particular Mennonite clockmaking tradition under consideration here begins with Johann Kroeger (1754-1823) of Reimerswalde near Marienburg, West Prussia, today's Malbork, Poland. In 1804 Johann left with his wife and children, his two cows, two pigs, a wagon, a spinning wheel, five loads of hay and continued his clock making craft in the village of Rosenthal in Chortitza, the so-called "Old Colony" of Mennonites in the Ukraine. Four generations of his descendants continued and expanded the manufacture of pendulum wall-hung clocks in Rosenthal which are known to this day as Kroeger clocks among Mennonites of Vistula Delta and south Russian origins from Canada to the United States, Mexico, Paraguay, Brazil, Germany and the southern Urals region of Russia.(2)

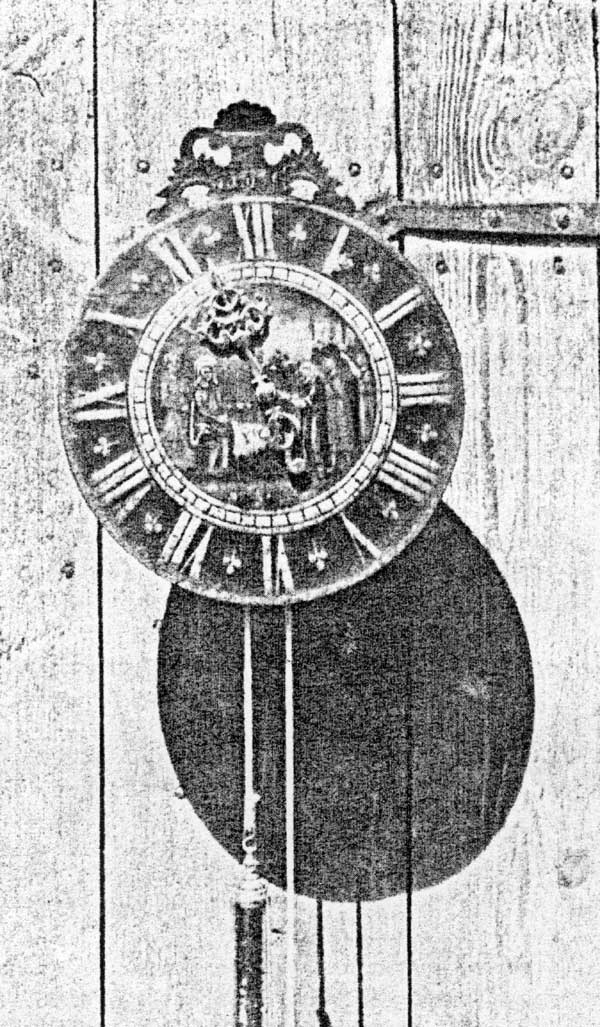

The historiated Kroeger clocks which are the focus of this discussion are of the older and now rather rare circular face type, superficially similar to the so-called Telleruhren. By the mid-19th century the square clock face crowned by a half circle became the dominant clock type manufactured by the Kroegers in Rosenthal, the same face type that was also produced by the other three Mennonite clockmaking firms in the Ukraine's Chortitza and Molotschna colonies: Peter Lepp of Chortitza, C. Hildebrandt, and Gerhard Mandtler of Lindenau in the Molotschna Mennonite settlement.(3) After the 1830s biblical imagery no longer decorates these clock dials. Instead floral and landscape motifs prevail, often in the form of mass-manufactured decals. In the 1930s the Kroeger family's clock manufacturing and repair business came to an end due to the social and economic upheavals of the post-revolutionary civil war in Russia and Stalinist purges of Mennonites and their subsequent flight to Canada and South America.

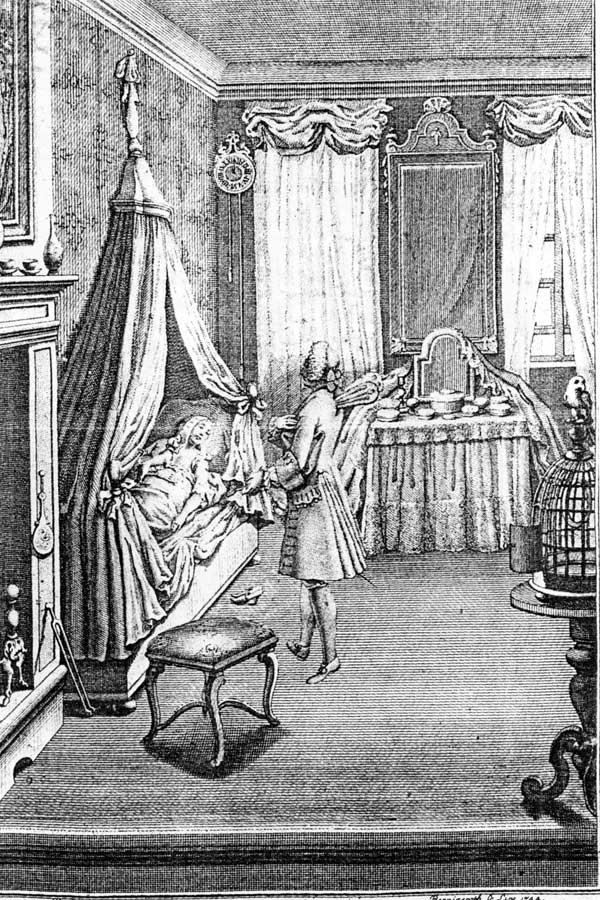

To the best of my knowledge nothing has been published on this particular early Kroeger clock type in the extensive literature on clocks and clock making in Europe.(4) The only studies which have included this clock type from the Vistula Delta are a 1930s publication on folk art in the region of Danzig and my own work on Mennonite material culture. The form, with its characteristic decorative "crown," has 18th century prototypes in Germany as illustrated in a 1744 engraving "An Elegant Bed Chamber in Leipzig" by A. Vernarin,(5) ( fig. 3) in mid-18th century South German Telleruhren, as well as in a 1750s peasant clock type made in Switzerland.(6) (Fig. 4)

Fig 3: "An elegant bedchamber in Leipzig," 1744, engraving by A. Vernarin |

Fig 4: Christ and the Woman at the Well, Swiss Peasant Clock, ca. 1750 |

The Hezekiah Clock(7)

When I first encountered what I later was to call the "Hezekiah clock," the family who owns it no longer knew the meaning of the image painted on the clock face. Their forebears had brought it from West Prussia in 1876 on their migration to Nebraska. Painted on the dial is a king seated on an elevated throne in an open portico of a palace. His attributes of royalty are a golden crown on his turban and a scepter in his right hand. Confronting the king is a bearded man reading from a large piece of paper covered with letter-like markings. Two other men are standing between the king and the man reading the letter or scroll. Signs that these men are of lesser rank are their simple dress, bare heads, and placement below the throne. In the distance one sees a turban-clad man holding a horse by its bridle. On the horse we see a rider holding a scepter and wearing a crown on his turban. This man, therefore, is most likely also a king.

The king on horseback and his groom are confronted in turn by a man who directs them with his right arm and extended index finger away from the enthroned king. In the distance on the horizon the artist painted the walls, towers, and spires of a city.

If we assume that the source of the story is biblical, then the setting with two kings, an audience and a letter in the very center of the image - coincidental with the pivotal point of the clock's hour hand - takes us to the Old Testament. Because of its central position the letter must be of special significance. But in which Old Testament story does a letter play a central role? I propose that this must be the story of King Hezekiah, seated on his throne, listening to a threatening letter brought by the Assyrian King Sennacherib's messengers. (2 Kings 19:9-15). Then Hezekiah prayed to the Lord to be saved from the hand of King Sennacherib, and the Lord answers Hezekiah through the prophet Isaiah concerning the Lord's plan for the Assyrian king: "... Because you have raged against me and your arrogance has come to my ears, I will put my hook in your nose and my bit in your mouth; I will turn you back on the way by which you came;" and "... By the way that he came, by the same he shall return; He shall not come into this city, says the Lord. For I will defend this city to save it, for my own sake and for the sake of my servant David." (2 Kings 19: 28 and 33-35). The figure confronting the mounted King of Assyria and pointing him back in the direction from which he came pictorially demonstrates the promise of the Lord.

The artist has joined several episodes of the story of Hezekiah in one image for the sake of brevity and completeness of content. Between the antagonists, the letter, or scroll, acts as a catalyst in the conflict, bringing about a turning point in the story. The scroll was understood as a symbol of prophecy. The whole scene reads like a shorthand version of Hezekiah, with the density of meaning found in emblems and the didactic urgency of popular preaching. Hezekiah's story is a story about faith, about the power of prayer, about a God who gives potent signs of his might and who saves his chosen people from the enemy. God's condition for peace and prosperity is faithfulness to the covenant.

King Hezekiah's faithfulness to the Lord, expressed through fervent prayer, also reveals God as the master of time. The Lord promised to add 15 years to the king's life in addition to restoring his health and providing deliverance from his enemies (2 Kings 20:5-6). In order to prove his promise to Hezekiah, the Lord alters time. He "[brings] the shadows back the ten intervals, by which the sun had declined on the dial of Ahaz" (2 Kings 20:11). Anyone who knew the story of Hezekiah would have known this passage as well.

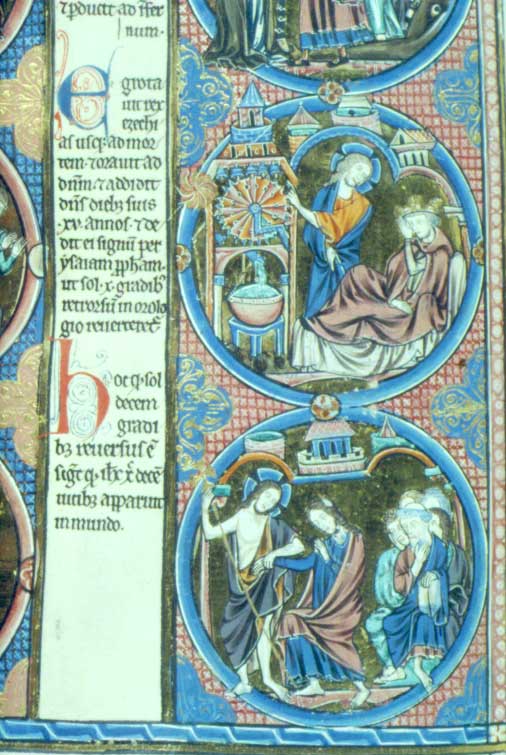

By looking at other examples of how the story of Hezekiah has been interpreted visually prior to 1800, the uniqueness of this particular image which focuses on Hezekiah's political dilemmas rather than on the miracle of the returned time makes our clock all the more compelling. It is this miracle of the Lord's turning back time - turning back the sun by ten degrees - that is the focal point of medieval illustrations, and not the Lord's turning back Hezekiah's enemy. One of the most frequently cited illustrations of God's gift of extra time is found in a late 13th century Northern French "Bible Moralisee" which is now in the Bodleian Library (MS Bod.270b, fol. 183v.) The roundel shows God in the center, turning the spokes of a water clock, of the type then still in use in medieval monasteries. King Hezekiah who was deathly sick at the time is shown reclining on his bed toward the right.(8) (Fig. 5)

Fig 5: God turns time back for the sick King Hezekiah, from a late 13th century Northern French "Bible Moralisee" |

Hezekiah's many-faceted story of trials of faith and rewards in terms of political success and health continued to inspire the creative energies of painters and musicians in the 17th century. Two works by Peter Paul Rubens deal with the defeat of Sennacherib, and Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722) composed his "Biblical Sonata IV: Hezekiah ill and recovered."(12)

However, none of these visual or musical interpretations of Hezekiah's story offer a direct prototype for the image that is painted on Johann Kroeger's Vistula Delta pendulum clock, purchased by a Mennonite farmer for use in his home. Hezekiah's story may have had special relevance for Mennonites in the Vistula Delta, under new Prussian rule in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Their rights and privileges, their religious freedom, their freedom not to bear arms, upheld by the Polish crown beginning in the sixteenth century, were now threatened and needed to be newly negotiated, not only with the Prussian crown, but also with the Protestant state church. For Mennonites in this political situation - one that threatened the continuity of their way of life as an autonomous community of believers - the story of Hezekiah's faithfulness and God's rewards for this faithfulness must have been a source of strength and comfort in the struggle to remain faithful in the face of opposition and loss of religious freedoms.

Mennonite theological writings seem mostly silent about Hezekiah, and that is due to the centrality of Jesus Christ as the model for living in this time, the "time of grace" as Menno Simons called our lives on earth. In his Foundations of Christian Doctrine he mentions Hezekiah once, along with other Isrealite leaders, as exemplary of faithfulness toward God: "Do not be Jeroboam, Ahab, and Manesseh any longer, but be David, Hezekiah, and Josiah so that you need not because of your office be ashamed in the great and dreadful day of the Lord, in that day which ... shall burn up as stubble all who have dealt unrighteously and have used violence upon the earth."(13) In the late 19th century John Holdeman, leader of the conservative congregations known as Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, also saw Hezekiah as an exemplary role model, but he emphasized Hezekiah as repentant sinner, not as faithful political leader. John Holdeman wrote in A Mirror of Truth: A Treatise that Hezekiah, like Saul and like Job, are to be understood as examples of God's testing "the children in relation to one another, in order that that which is in their hearts might be revealed ... so that they acknowledge their sins and may repent." (14)

The style of the painting points to the late 18th century as

the date when this clock face was decorated, corroborating the

possible pre-1800 date of Johann Kroeger's making of this clock

in Reimerswalde. The composition reflects standard Baroque

devices, albeit in a hand not academically trained: a grandiose

architectural setting for the main protagonist and a sudden, deep

vista. The execution is in a kind of quick but sure shorthand,

and highlights are placed effectively. The red color areas appear

very flat in contrast to those treated with blue and may have

been painted over. The question remains whether the painter of

the clock - was it a wife or daughter or apprentice of the clock-maker? - worked from a prototype image such as a popular print

or a historiated painted tile, or whether the composition was his

or her own unique invention. The former is more likely,

especially if one considers the enormous repertory of biblical

scenes painted on Dutch tiles in the seventeenth and eighteenth

century. Such tiles were used in Mennonite homes in the Vistula

Delta where the Dutch language continued to be the language of

religious services well into the second half of the 18th century,

and where there were strong personal, commercial, and church ties

to the Netherlands. The fact that two other of the extant

Kroeger clocks are each painted with the same biblical motif in

identical manner - the story of Jephtha's return - suggests that

the application of imagery onto clock faces was part of a serial

production and counter-indicates the probability of original

compositions, unique to each manufactured clock. Yet, the

prototype for the Hezekiah clock remains to be found.

The Jephtha Clocks

According to David H. Epp's biography of his grandfather, the Mennonite clockmaker and factory owner Peter Lepp (1817-1871), the story of Israel's military hero Jephtha being greeted by his daughter upon his return home after defeating the Ammonites (Judges 11:29-40) was a fairly common image on such clocks. Epp writes about Peter Lepp's apprenticeship to a clock maker named Janzen in Prussia, one of his relatives there. Lepp returned to Chortitza in 1836, became very successful building agricultural machinery and came to be called the "father of German factory industry in our colonies." David H. Epp remembered: "On the round clock face one usually saw King Jephtha high on a horse, joyfully received by his daughter and her friends, but the King, bound by a rash vow, has to greet her with the words "Oh, my daughter, you make me sad (you fill my heart with sorrow.)"(15)

Two such clocks are now in North America, one brought by a Mennonite immigrant family in the 1870s to Henderson, Nebraska, the other is in a private collection in Kansas, having been discovered in a clock repair shop's storage in Topeka, Kansas, a critical railroad destination for many of the 1870s Mennonite immigrants to Kansas. On each one of these two clocks the image of Jephtha meeting his daughter at the gate to his home matches Epp's recollection perfectly. But being unaware of Epp's account and due to the disinterest in Jephtha in 20th century religious and popular culture, the current owners of the Jephtha clocks, just like the owners of the Hezekiah clock, did not understand the meaning of the image. Indeed, Jephtha's rash vow and the sacrifice of his own daughter is hardly the subject of Mennonite sermons at the turn of the 2nd millennium. To the uninitiated the image might as well represent a fairy tale, a medieval knight wooing his lady love. One of these clocks was "restored" in the 1970s, the image re-painted in a Nebraska clock-repair shop without knowledge of the story's original meaning. Luckily, the restorer followed the original image very literally, as can be verified by a comparison with the second extant Jephtha clock whose painted dial is rather damaged but still reveals the original image of this Old Testament tragedy. (Fig. 6)

Fig 6: Jephtha greeted by his daughter, restored painting on pendulum clock, Vistula Delta or Molotschna colony, early 19th century, private collection. Photo: Burton Buller |

But for earlier centuries the story of the military hero Jephtha contained several lessons: obedience to one's promise to God - in the form of keeping one's sacred vow even at the expense of losing one's only, most cherished child; and the virtuous daughter's glad acceptance of her father's sacred duty toward God.

Jephtha and the sacrifice of his virginal daughter has captured people's imagination since the early Church. Typologically he was regarded as a prefiguration of Christ's sacrifice on the cross, while his daughter was considered a prefiguration of the Virgin Mary, consecrated in the Temple. (16) Kurt Weitzmann, in his discussion of the 7th century Jephtha panel in the church of St. Catherine's monastery on Mount Sinai, has shown that Church Fathers held opposing views on Jephtha's rash vow. Some condemned Jephtha's motivation of his sacrifice of his daughter, others lauded his act which to them constituted the typological parallel between the sacrifices of Jephtha and Christ.(17) The Jephtha story remained very much at home in narrative cycles of medieval book illumination.(18) For example in the concordantia caritatis, which aimed at aiding clerics in the preparation of homilies, the lament of the daughters of Israel over Jephtha's daughter (Judges 11: 40) is paired analogously with the lament of the women under the cross (Luke 23: 27), and the lament over Josias (2. Chr. 35: 25).(19)

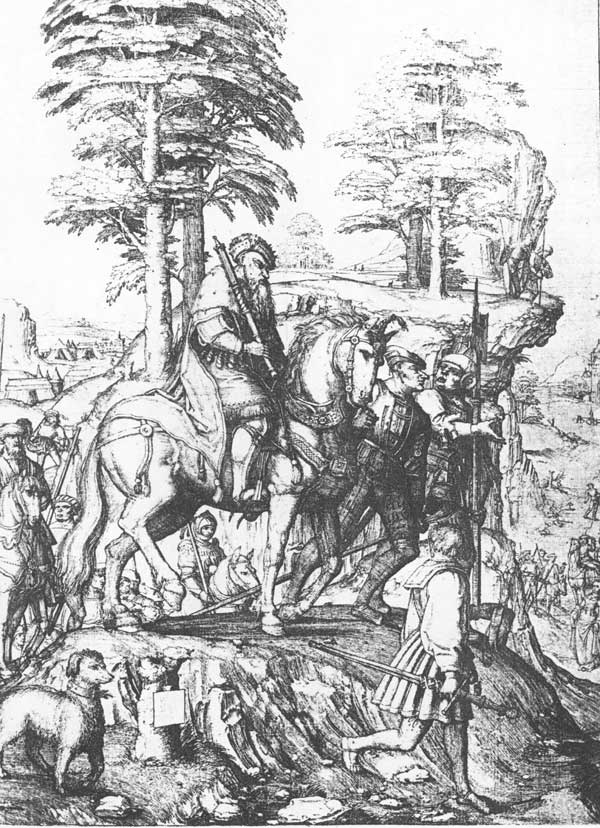

From the 16th century on, the episode pictured on the 18th century Vistula Delta clock under consideration here, Jephtha's daughter receiving her father with music and dance after his return from his military victory, has been more frequently represented in art than her sacrificial death by her father's hand. Lucas van Leyden created a painting for each episode.(20) The fact that Adam von Bartsch (1751-1821) gave Lucas van Leyden's engraving of around 1508 the title "The Daugher of Jephtha," suggests that in the latter part of the 18th century, when our clock was made and decorated, this theme was very much part of the public consciousness. Recent scholarship has made a convincing case that van Leyden's theme in this engraving probably concerned Abigail and David. Both Abigail and Jephtha's daughter conducted welcoming parties for distinguished military heros, and van Leyden's iconography is applicable to either story.(21) (Fig. 7)

Fig 7: Jephtha greeted by his daughter, engraving by Lucas van Leyden, ca. 1508, Bartsch no. 24 (350) |

When Jost Amman illustrated Luther's German Bible with 142 woodcuts - printed in 1565 - he included the scene of Jephtha's daughter, together with her maidens, joyfully receiving her father in front of the gates of his home. This composition, which gives equal visual weight to both protagonists, constitutes the earliest and closest prototype to the image painted on the Vistula Delta clock.(22) (Fig. 8)

Fig 8: Jephtha greeted by his daughter, woodcut by Jost Amman, 1565 |

The continued popularity of Jephtha's story throughout the 18th century is attested to in many prints and paintings produced by Dutch, German, French and Italian artists. Of these works the only one which would have been accessible for viewing in the Vistula Delta was Lorenz Lavenstein's painting (ca. 1540) of Jephtha's return in the Artushof of Danzig (Gdansk).(23)

Another strong factor for keeping the story of Jephtha alive were its musical incarnations, for example Maurice Greene's oratorio Jephtha (1737), followed in 1751 by Handel's oratorio Jephtha. Subsequently this work was enthusiastically received also in the German speaking realm, where choral societies and musical festivals spread performances of Handel's oratorios in the first half of the nineteenth century.(24) Handel's librettist Morell purged and altered the proportions of the biblical source in order to emphasize the theme of conflict between public and private interest, to shape a story of moral politics on the part of the Israelites which was to serve the British audience as a model for political leadership that places the interest of the nation above personal interest.(25) This shows how biblical stories could be visually or musically used - if not abused - to justify convenient points of view in matters of faith and politics.

But late 19th century biblical scholars such as Emil Zittel did not necessarily paint Jephtha's fateful vow in a positive light. In his highly popular work Die Entstehung der Bibel he suggested that Jephtha was motivated by a single-minded thirst for power, and a merely superficial adherence to obligations of faith.(26) In early 19th century American folk art and in American mid-19th century paintings the story of Jephtha's return also occurs, but in this context the emphasis seems to be on the daughter as heroine and role model, rather than the father. One can assume that in early 19th century European visual culture Jephtha's story was a similarly popular subject matter.(27)

Menno Simons did not cite Jephtha, nor Jephtha's daughter, among his Old Testament's examples of faithful living. However, in late 20th century Anabaptist feminist theological writing, the respectful response of Jephtha's daughter to her father's decision has been made the focal point for constructing a "contemporary model of God as friend" which "has potential for modern women."(28)

Biblical themes other than that of Hezekiah and Jephtha were most likely featured as well on Mennonite-made clocks. This is suggested in a unique photograph of a clock inscribed with the date 1795, taken in the 1930s on a Mennonite farm in Tiegenhof, Vistula Delta, Poland, then West Prussia. The image on the dial suggests the story of Epiphany: On the right half three kings or wise men pay homage to the Christ Child, Mary and Joseph are seen on the left half of the dial.(29) (Fig. 9) There is a strong likelihood that faces of Mennonite-made clocks of this type which were originally decorated with biblical narratives were re-decorated at a later period in their long lives, following fashion or because the story represented had fallen out of favor or was no longer understood. Such might be the case of a clock that was brought to Kansas from Alexanderwohl, Ukraine, in the 1870s migration, now in the Mennonite Heritage Museum in Goessel. (Fig. 10)

Fig 9: Nativity or Epiphany (?), pendulum clock, Vistula Delta, dated on clockface 1795 |

Fig 10: Pendulum clock, from Alexanderwohl, Ukraine, date of dial 1833, clockface was possibly repainted after 1833. Mennonite Heritage Museum, Goessel, Kansas, L 93.1. |

Of Time and Faith: the Hezekiah and Jephtha Clocks in Context

In order to understand the Hezekiah and Jephtha clocks in the context of their time, it is helpful to consider these objects within the larger tradition of the relationship between time and religion as expressed in related iconography.

The 1532 German edition of Franciscus Petrarcha's treatise Von der Artzney bayder Gluck (Of Medicine's Twofold Fortune)features in its 15th chapter a dialogue between Lament and Reason about the loss of time. The accompanying woodcut shows a bearded man in his study, leaning on his table with both elbows, his head supported by both hands. (Fig. 11)

Fig 11: "Von Verlierung der Zeit" (Of the Loss of Time), woodcut in 1532 German edition of Franciscus Petrarcha's Von der Artzney bayder Glueck / Des Guten und Widerwaertigen |

|

Gewiss ist es den Menschen darzy geporn / Ihm darzy die zeit verlihen sein / das er seinen schoepffer eere / liebhabe / und bedencke / was daran fellt / verleurt man ungezweyfelt / Nunn sehent wie vil der verlorne und nit verloren zeyt sey.(30) |

The moral to be drawn from this hypothetical conversation is that the only time that is lost to a man or a woman is time not spent to honor, love, and contemplate his or her Creator, as this is the only purpose for which man was given time. Two objects in the scholar/cleric's study that serve such a devotion to God are the prayer beads on the man's belt and the whip for self-flagellation which is hung on the wall next to one of the three time-measuring pieces.(31)

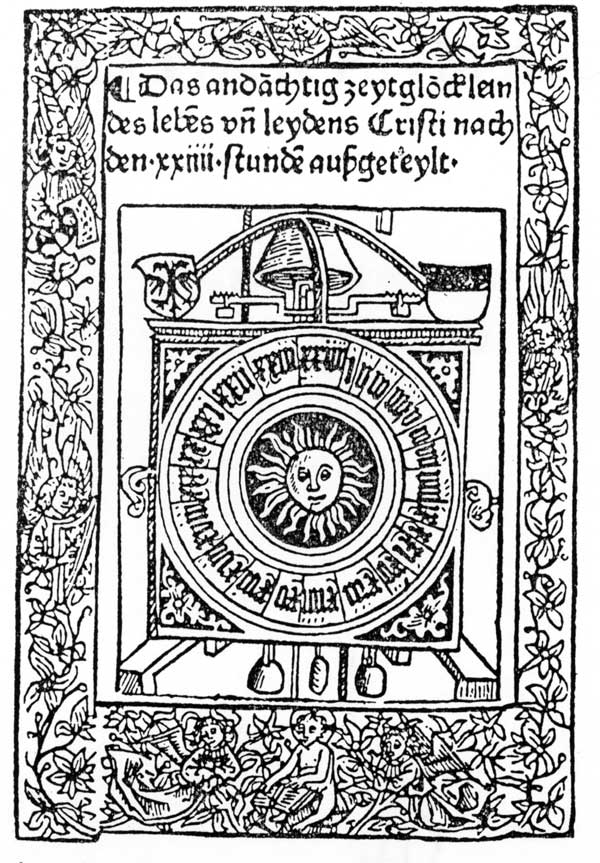

The idea that time on earth should be spent honoring God is of course central to the medieval Book of Hours, and it is visually expressed in the design of many clocks. Examples from the 15th century include Paolo Uccello's 1443 fresco for the clock face of Florence Cathedral which features the haloed heads of the four evangelists, while the hour hand combines the form of the cross from which a burst of light radiates like the light of the sun. Similarly, the title page of the German edition (1493) of Bertoldus-Berthold von Regensburg's Horologium devotionis circa vitam Christi (1346) features in the center of the clock face a radiant sunburst, symbol of the cosmos as well as of Christ's Resurrection.(32) (Fig. 12)

Fig 12: Title page: Das andaechtig Zeytgloecklein des Lebens un Leydens Christi nach den 24 Stunden aufgeteylt. Bertoldus-Berthold von Freiburg, Ulm 1493. |

The omnipotence of God as Creator of the universe and of Time is quite literally depicted on a 16th century clock in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Above the dial, emerging from the clouds, is the image of God as ruler of the world, his right hand in the familiar gesture of blessing, his left holds the globe topped by a cross. Heads of putti personify the winds blowing from the four directions.(33) By the time Filippo Picinelli's Mundus Symbolicus was published in 1694 the "Raederuhr", (Horologium Rotatum), had become a multivocal, multifaceted symbol of God's order and justice and man's life course - seven whole pages of text discuss all possible symbolic meaning of the clock, after devoting seven pages to the symbolic meaning of the sun dial (Horologium Solare).(34)

The use of the image of the clock as a moralizing metaphor for human conduct is illustrated in Jan Luyken's best seller Het Leersaam Huisrad ("The Tutelary Household"), published in Amsterdam in 1711. (Fig. 13)

Fig 13: "Het Horologie" from Jan Luyken's Het Leerzam Huisrad, 1711. |

Many examples of clocks decorated with biblical symbols and narratives have been documented from the 16th through the first half of the 19th century. But the motifs are for the most part taken from the New Testament: The Annunciation, Visitation, the Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, the Holy Family, Christ and the Samaritan Woman, Christ in Gethsemane, the Flagellation, Christ Crucified, the Conversion of Paul. In contrast, Old Testament imagery on clocks is relatively rare. Published examples show the Fall and the Tower of Babel, in addition to the two Old Testament themes on the Vistula Delta domestic clocks discussed in this essay. Thus, seen in this wider context, the latter remain unique within the body of documented clocks.(36)

Anabaptist/Mennonite Relationships to Time

An Anabaptist/Mennonite relationship to time involves a strong conviction, at best commitment, that time should be sanctified by active discipleship. This is expressed in written and visual sources.

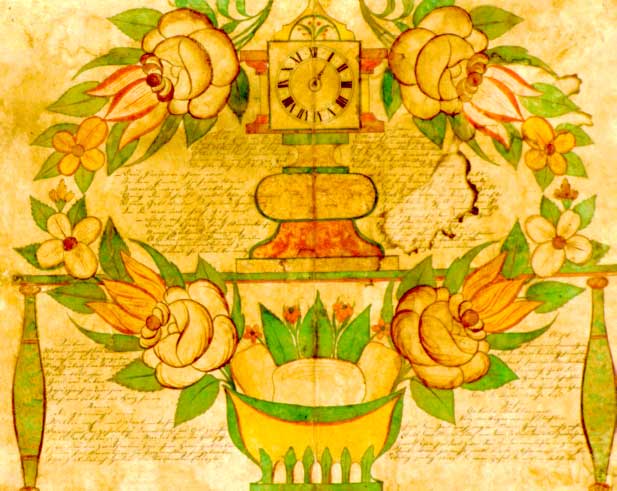

Among late 18th and 19th century examples of Mennonite illuminated penmanship, known as Fraktur, at least one is preserved which expresses a strong consciousness that the hours of the day, human time, must be lived faithfully, in awareness of and therefore in preparation for death, judgment, and eternal life. In 1846 a member of the Mennonite community in Michalin, Polish Russia, wrote and embellished "Spiritual Wonder Clock," the title of a German poem which relates a passage from scripture for each of the twelve hours marked on a clock's dial, admonishing the continuous upholding of all major tenets of faith. (Fig. 14)

Fig 14: "Spiritual Wonder Clock", 1846, anonymous, from Michalin, Polish Russia, private collection. Photo: Mark Wiens. |

"One--need we have on earth, that is Jesus

Two--paths: one narrow and one wide

Three--persons we honor in one being: Father, Son and Holy Ghost

Four--things exist before the Soul: death, judgment, heaven, and

hell;

Five--wounds of Jesus I see on the cross

Six--days the Creator used to build a lovely earth

Seven--words Jesus spoke as He died on the cross

Eight--people stood in grace as the flood was rushing on; may

Jesus too be your ark

Nine--who were cleaned but did not give thanks

Ten--commandments are before my eyes

Eleven--of the twelve were true to Jesus

Twelve--tribes were as twelve pearls to Zion's counsel"(37)

In essence, this work on paper may be considered as a mid-19th century Protestant variation on the theme of the medieval Book of Hours or the Zeitgloecklein. In addition to the text, both on this fraktur as well as on the frontispiece for the Zeitgloecklein, the images of the clocks respectively serve as a moralizing emblem without itself bearing explicit religious narrative imagery.

This joining of a moralizing text with a clock can be observed in parallel contexts of Mennonite life by the mid-19th century. When, following the 1830s, religious motifs were no longer painted on the dials of Mennonite-made clocks, moralizing mottos (Sinnsprueche) were sometimes placed on clock cases in the living rooms of well-to-do Vistula Delta farmers, as recorded by a German ethnologist who studied the material culture of the region in the 1930s. For example, "I run quickly, oh man, think of the end" ("Ich lauf behende, o mensch, bedenk das Ende!") and "Here goes time, there comes death, o man, act justly and fear God!" ("Hin geht die Zeit, her kommt der Tod, o Mensch, tu recht and fuerchte Gott!").(38)

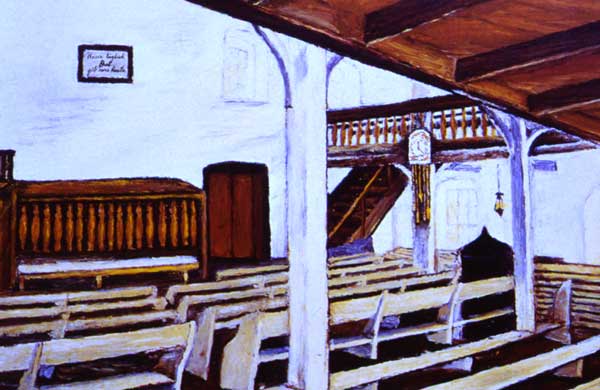

The same type of wall pendulum clock that was a key furnishing in Mennonite homes in the Vistula Delta and in the Mennonite colonies in the Ukraine was also hung in Mennonite meeting houses, literally "prayer houses," as well as mottos. Clock and motto were the only decorations in the otherwise plain interior of the prayer house, placed there however not as adornment, but as didactic devices for religious admonishment. Henry Pauls remembered the debate among the members of the Chortitza Mennonite church, built in the 1830s, over whether to put a clock into the worship space, thereby acting against the Anabaptist prescription of plainness.(39) Pauls relates that this clock was installed "only after debates about the appropriateness of having a clock in a church at all, and only after the chimes had been disconnected." (Fig. 15)

Fig 15: Chortitza Mennonite Church, Chortitza, Ukraine, painting by Henry Pauls. From A Sunday Afternoon: Paintings by Henry Pauls. 1991, plate 21. |

This combination of Kroeger clock and hand-painted wall mottos of scripture could be seen in a number of the new prayer houses in the Orenburg region in the southern Ural plains of Russia, built in the late 1970s and 1980s - and then deserted because of Mennonite mass migrations from the Soviet Union to Germany in the early 1990s. For example, Zdhanovka's prayerhouse of the Kirchliche featured a Kroeger clock, a motto painted onto the chancel "Wir predigen Christus den Gekreuzigten" (We preach Christ crucified) - a statement of faith in the redemptive power of the crucified Christ - in addition to mottos hung on the walls. (Fig. 16) Similarly, the prayerhouse of the Kirchliche in Pretoria featured a clock in the center of the elevated chancel platform, a clock symmetrically framed by two behind-glass-paintings illustrating scripture verses.(40) (Fig. 17)

Fig 16: Kroeger pendulum clock and Christian motto near chancel of the prayer house of the Kirchliche Gemeinde, Zhdanovka, Orenburg region, Russia, 1991. Photo: John M. Janzen. |

Fig 17: Electric clock between two paintings with mottos above the chancel of the prayer house of the Kirchliche Gemeinde, Pretoria, Orenburg region, Russia, 1991. |

It is noteworthy for this discussion of the relationship between time and faith that the Lone Tree Church of God in Christ Mennonite (Holdeman) near Moundridge, Kansas, built in the 1970s, features a plain electric clock in the same general location as is typical for the placement of clocks in the Russian Mennonite churches just described, namely on the wall with the chancel or platform for male worship leaders, in the center of which is the pulpit. In these worship spaces the believers face the clock, while in most mainstream contemporary American Mennonite churches a clock is placed in the back of the congregation and a cross is placed in front. Because the Holdeman Mennonite leadership's strict proscription of simplicity there are no mottos, no posted scripture verses, of course no "graven images" of any kind, so that the clock is the absolutely only visual focal point in the severely plain interior. What might it mean that in this gender separated, patriarchal, and hierarchical environment the clock is placed facing the men's and not the women's side?(41) In such settings then, where there is neither cross nor any other icon, the clock takes on iconic qualities.

This plain Holdeman church with its clock near the chancel

has an uncanny parallel in the former Witmarsum Mennonite meeting

house in the Netherlands, built in the early 18th century. An

engraved view of its interior shows an hourglass behind the

chancel on the otherwise completely plain wall.

"Now is the Time of Grace"

The image of the clock dial itself is temporal - as is the running of the sand in the hourglass - and expresses eo ipso what the hymns admonish the believers to do: to live with the finiteness of time in mind, to acknowledge time as a gift of God that warrants stewardship. When our two Old Testament clocks ticked and rang the hours in Mennonite living rooms in the Vistula Delta, their owners worshiped at home and in plain prayer houses with the help of a German hymnal, printed on the West Prussian Royal Court Press in 1780 Marienwerder near Gdansk.(42) The foreword states that the book is intended for use in the home as well as for congregational worship, and that its ultimate purpose is to prepare the community of believers for eternal life. This eschatological emphasis is certainly absent in the foreword's statement of purpose in the Hymnal: A Worship Book (1992) which is used by many North American Mennonite congregations today. Here there is only mention that the use of the hymns should strengthen faith, nothing is said of eternity.(43) This shift from a "restrained" eschatology(44) which the Anabaptists adopted in the 16th century to a minimalizing of eschatology 500 years later is a reflection of a changed concept of time - in the sense of secularization of time - which in turn is manifest in the decreasing numbers of today's hymns dealing explicitly with time.

In the 1780 Mennonite hymnbook which was used when our clocks marked the hours and the days of Mennonite families in the Vistula Delta, one finds under the heading "Of the Christian Life and Faith Journey" (Vom Christlichen Lebenswandel), 94 hymns of which four address the sub-theme of "Regarding faithfulness in temporal vocation" (In der Treue des zeitlichen Berufs). Hymn 394 compares man to a time's speck of dust (Staub der Zeit) whose wit, scheming and planning amount to little unless man recognizes his weakness and asks God for guidance in his daily work and endeavors. Only then will one's work be blessed. Four more hymns deal explicitly with "The right Use of Time," (Bey dem rechten Gebrauch der Zeit). In this same hymnbook the theme of time is again central in hymns dealing with dying and death - twelve alone are devoted to the theme "Thinking of Death during healthy [sic] days" (Vom Andenken des todes bey gesunden Tagen), and six hymns deal with preparation for approaching death (Bey Herannahung des Todes), while time is not a subject in mourning hymns sung specifically at the time of a funeral - and finally time is a central subject in hymns that speak of eternal life. In contrast, the 1992 American Hymnal: A Worship Book has no equivalent categories for "general songs for dying," nor songs for preparing for death. It does offer three songs specifically for funerals and thirteen for a thematic category which combines Death/Eternal Life. Still, this contemporary hymnbook acknowledges, as did the medieval Book of Hours, "All time is yours, O Lord to give, May we, in all the years we live, find that each day of life is new, a celebration, Lord with you," (No. 48), or, "This is the day the Lord has made, he calls the hours his own..." (No. 642).

Hymns to mark the New Year gained remarkable prominence between 1780 and 1854, the publication of the next Mennonite hymnal used in the Vistula Delta communities. While the 1780 hymn book contains one New Year's song as an appendix, the 1854 Mennonite hymnal offers twelve songs celebrating the New Year as part of the hymnal's cycle of "Christian celebrations." This christianization of celebrations of civil society might reflect the "Prussianization" of Mennonite religious culture in the Vistula Delta. New Year's hymns in the 1854 song book (for example numbers 141-143) focus on acknowledging God's rule over time and eternity and His eternal faithfulness and extended grace toward men. New Year is seen as a time for repentance and new beginning for one's responsible, meaning Christian, use of time. And the hymns which are to aid a person's "christlicher Wandel" urge again and again to use one's time wisely, for good and just works for one's neighbor in need, for widows and orphans, (No. 557) in view of eternity when it is too late for regrets. Similarly, numerous late 18th and 19th century fraktur pieces are New Year's greetings, often given by children to their parents, with verses expressing gratitude to God for another year of life blessed by God's gifts of sustenance and hope.

Catechisms which were published in the latter part of the 18th century taught that the most necessary thing a person should strive for in this life is to live in God's fellowship and grace and to obtain eternal salvation in the hereafter; that a person must provide for his bodily needs in a Christian manner, seeking first the kingdom of God and His righteousness in this life; that the kingdom of God in this time resides in all believers and consists of justice, peace, and joy in the Holy Spirit, but that nachmals [after death] the kingdom of God is eternal life with God and all the saints. (Katechismus, Elbing, 1778)

For Menno Simons, a Catholic priest who converted to Anabaptist Protestantism in 1533, Christianity meant a practical Christianity, a way of life on this earth which followed Christ's model and Christ's teaching. His motto was 1 Corinthians 3:11 "For other foundation can no man lay than that is laid, which is Jesus Christ." That is why in his writings he emphasized the message of the New Testament, with occasional reference to the major Old Testament prophets as models of faith, and the few references he made to the fates of Old Testament villains - violent, cruel, unrighteous people like Hezekiah's adversary Sennacherib(45) - serve as examples of God's judgment and wrath. For Menno's purposes, Hezekiah and Jephtha were not important, but Christ's Sermon on the Mount was.

Man's life on earth passes in what Menno called "time of grace" and "days of grace," and he reminded his fellow believers that "the time of grace remaining is short" so that they might strengthen their effort to live the kingdom of God on this earth.(46)

Thus we have seen that the biblical images on these early Kroeger clocks demonstrate an acute sensitivity to bringing human time into close connection with eternal time by exploring how these artifacts express a sense of time distinctive to Mennonites within the broader European context of biblical iconography on clocks. Because clocks are visual markers of the passage of time, persons of faith may perceive them as indicators of the finiteness of life, as a reminder of death. For people who believe in an eternal life, the way time is lived on earth must involve constant awareness that the order of the universe is ordained by God, hence the Creator God is acknowedged as the Master of Time. Biblical narratives painted on clock faces mediate sacred time, between God's time and the passing time of the everyday world and mortality.

Clocks are by definition and by function symbols of time.

But this study of biblical iconography painted on clock faces

tells us something distinctive of a community of believers caught

in cross-currents of European history. Their religious outlook in

which time was sacred pervaded the work-a-day world. While the

story of Hezekiah was generally understood as an allegory of

God's power over time - He extends and retracts it - both the

Hezekiah story and that of Jephtha and his daughter function as

didactic devices and symbolic models on how to live one's time

faithfully in the face of God.

Afterthought

Given the historically iconoclastic stance of Anabaptist teaching, the absence of religious imagery in Mennonite prayer-houses - with the exception of late 20th century acculturated liberal Mennonite denominations in North America - it is curious that around 1800 Mennonite clock-makers made and sold clocks with biblical imagery. This might reflect the wider cultural practice of decorating household objects with religious imagery, not just clocks, and it may reflect Mennonite production for a non-Mennonite market, as well as for a Mennonite market. A second aspect of these clocks seems to be at odds with Anabaptist/Mennonite teaching, and that is pacifism. Both clocks presented here feature Israelite military heros. But then, it is not military heroism which is central in each image, bu rather the very human struggle of how to remain faithful to God while living in a world of politics and power struggles.. This is a struggle that the Anabaptist/Mennonite religious minorities in Prussia and in Russia identified with, especially its leadership which needed to constantly negotiate with both of these 19th century "super powers."

Notes

1. 2 Cor. 6:2. Menno Simons, "Foundation of Christian Doctrine," in The Complete Writings of Menno Simons (Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1956), 110.

2. Arthur Kroeger, "Kroeger Clocks," n.d., n.p., photocopied manuscript, compiled between 1981 and 1996; parts of this manuscript were prepared for the exhibition "Turning Back the Hands of Time," an exhibition of some 200 timepieces made and used by Mennonites, at the Mennonite Heritage Village, Steinbach, Manitoba, May 1-Dec. 15, 1995. The exhibition included over thirty wall clocks. See also N. J. Kroeker, Erste Mennoniten-Doerfer Russlands, 1789-1943 (Vancouver, B. C.: N. J. Kroeker, 1981), 92-98.

3. The Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. I (Scottdale, Pa.: Mennonite Publishing House, 1969), "Clocks," p. 629. See also Vol. V (Scottdale, Pa.: Herald Press, 1990), "Clocks," p. 166.

4. Nine of eleven known clocks of this type are in private collections and Mennonite mueums in the United States, Canada, and Russia. The fate of the clock photographed on a Mennonite farm in the Vistula Delta in the 1930s and published in H.B. Meyer's Deutsche Volkskunst: Danzig, (Weimar, n.d.), ill. 68, is unknown. This book, as well as the author's Mennonite Furniture: A Migrant Tradition 1766-1910 (1991), are the only publications which feature this Vistula Delta clock type as part of Mennonite material culture, not in terms of the history of clocks or clocks as decorative arts.

5. This is an illustration for the German translation by Luise Gottsched of Alexander Pope's Rape of the Lock, published in Peter Thornton, Authentic Decor, The Domestic Interior 1620-1920 (New York: Viking, 1984), 122, ill. 150. For a discussion of Telleruhren see R. Muehe, Uhren und Zeitmessung.

6. Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan, Uhren (Braunschweig: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1961), 303, ill. 237.

7. The iconographic interpretation posited here was first published by the author in Mennnonite Furniture, A Migrant Tradition, 1766-1910 (Intercourse, Pa.: Good Books, 1991), 98-101.

8. Andre Wegener Sleeswyk, "The 13th Century 'King Hezekiah' Water-Clock," Antiquarian Horology, 488.

9. Erlangen UB Ms 121 fol. 171v., first half of the 13th century, illustrated in Engelbert Kirschbaum, editor, Lexikon der Christlichen Ikonographie, Vol.I (Freiburg: Herder, 1968), 714-715.

10. Lexikon der Christlichen Ikonographie, Vol. I, 714-715.

11. Wilhelm Waetzoldt, Hans Holbein der Juengere (Berlin: G. Grotische Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1938), 150.

12. A. Pigler, Barockthemen, 2nd ed., Vol. I, p. 184. He records one drawing and one painting on the theme of the defeat of Hezekiah's foe, the Assyrian king Sennacherib.

13. The Complete Writings of Menno Simons, 106.

14. John Holdeman, A Mirror of Truth: A Treatise, For the Instruction and Comfort of the just and For the Conversion of the Unsaved. Translated from : Ein Spiegel der Wahrheit, 1878, (Hesston, Kan.: Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1956).

15. David H. Epp, "P.H. Lepp," Der Bote, Rosthern, 1928, No. 10ff; reprinted in Der Bote, July 13, 1938. See also "Lepp, Peter Heinrich" in The Mennonite Encyclopedia, III, 327.

16. Louis Reau, Iconographie de L'Art Chretien (Paris, 1955-1959), vol. 2, p. 234. It is in terms of this typology - Jeptha=Christ, his daughter=Mary - that Jephtha is presented in Filippo Picinelli's Mundus Symbolicus, printed in Cologne in 1694. See the 1976 edition edited by August Erath, Vol. I, (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1976) 197.

17. Kurt Weitzmann, "The Jephtha Panel in the Bema of the Church of St. Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai," Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 1964, 341-342.

18. Lexikon der Christlichen Ikonographie II, 384-388.

19. Otto Schmitt, Reallexikon zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte, Vol. 3, pp. 833-852, esp. pp.845-848.

20. A. Pigler, Barockthemen (1974), 119. He recorded Lucas van Leyden's painting of Jephtha met by his daughter upon his return in the collection of the art dealer J. Goudstikker, Amsterdam, illustrated in catalogue 39, 1930/31, No. 33, whereas Reau lists this painting under the theme of "The Sacrifice of Jephtha's daughter," p. 236. Reau lists Lucas van Leyden's painting of Jephtha's daughter meeting her father in the colllection Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Reau, Iconographie, 235.

21. Bartsch no. 24 (350), in Walter Strauss, ed., The Illustrated Bartsch, Vol 12 (New York: Abaris Books Inc., 1981), 156; Ellen S. Jacobowitz and Stephanie Loeb Stepanek, The Prints of Lucas van Leyden and His Contemporaries (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1983), 40-42.

22. The Illustrated Bartsch, Vol. 20, p. 267, Fig. 1.38 (365).

23. Pigler, 119-121; Pigler lists fifteen works by Italian masters of the 17th and 18th centuries, seventeen Dutch artists who dealt with the Jephtha theme, seven French and six German works for the 17th and 18th centuries. Reau's list of works on the subject of Jephtha's daughter meeting her father only names 5 works for the 13th through the 19th century. Reau, 235.

24. Christopher Hogwood, Handel (Thames and Hudson, 1984), 222-223, 250-253.

25. Ruth Smith, Handel's Oratorios and Eighteenth Century Thought (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 236-239, 340-345.

26. Emil Zittel, Die Entstehung der Bibel, 5th edition (Leipzig: Philipp Reclam Jr., 1891), 50. The first edition was printed in 1872, and there is a 1995 reprint of the 1891 edition.

27. See for example Betsy B. Lathrop's 1812 watercolor on silk, Jephtha's Return where the delicacy and decorativeness of figures and setting hardly convey the tragic dimension of this homecoming reception. This work is in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection, Williamsburg, Virginia. John Dillenberger mentions Hezekiah Augur's 1828 painting Jephtha and His Daughter, William Page's 1840 painting Jephtha's Daughter, and Chauncey Ives' Head of Jephtha's Daughter of 1845 in the context of his discussion of the prominence of Old Testament (and New Testament) heroines in early 19th century American art. See John Dillenberger, The Visual Arts and Christianity in America (New York: Crossroad, 1989), 130, 245.

28. Mary Schertz, "God as Friend: Jephtha's Daughter, Judges 11:29-40," Perspectives on Feminist Hermeneutics, Gayle Gerber Koontz and Willard Swartley, editors. Occasional Papers No. 10 (Elkhart, Ind.: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1987), 83-96. Schertz draws her interpretation from Phillys Trible's essay "The Daughter of Jephtha: An Inhuman Sacrifice," in Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981), 93-116.

29. H.B. Meyer, Deutsche Volkskunst: Danzig (Weimar: Verlag Boehlau, n.d.), ill. 68, no page number.

30. Manfred Lemmer, ed., Franciscus Petrarcha: Von der Artzney Bayder Glueck / Des Guten und Widerwertigen (Friedrich Wittig Verlag), chapter 15, "Von Verlierung der Zeit." See also Franciscus Petracha: Von der Artzney bayder Glueck (Augsburg: Heynrich Steyner, 1532; reprinted in Hamburg, 1984).

31. See also Walther Scheidig, Die Holzschnitte des Petrarca-Meisters (Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1955), 209. Scheidig's interpretation of the woodcut "Of the Loss of Time" is entirely secular, disregarding completely the sense of Petrarca's dialogue between Lament and Reason.

32. C. Spierdijk, Klokken en Klokkenmakers: zes eeuwen uurwerk 1300-1900 (Amsterdam: J.H. De Bussy, 1962), 51. The full title of the German translation of Bertoldus-Berthold's Horologium devotionis circa vitam Christi is "Das andaechtig zeytgloecklein des leben un leydens Christ nach den 24 Stunden aufgeteylt," published by Cunrad Dinckmut, Ulm, 1493.

33. Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan, Uhren, p. 13, fig. 6. The clock is dated on its face, 1545.

34. Filippo Picinelli, Mundus Symbolicus (Colgone 1694; New York: Garland, 1976), edited by August Erath, Vol. II, pp.187-194.

35. See C. Spierdijk, 158; see also Jan Luyken, Het Leerzaam Huisraad (Amsterdam/Leiden, 1711).

36. These examples are from the following publications:

Luiga Pippa: Orologi Nel Tempo, Da Una Raccolta (Milan: Vanni Scheiwiller), 80-81. This luxury clock is in a form of a book, dated 1592, by an anonymous

German master. The frontispiece shows the donor/owner praying under the crucifix, with the

inscription: "Crux Plasmatoris Defendat Nos Omnibus Horis," the back shows the

Annunciation with the inscription "Hora est de' Somno Peccati surgere," and "Mater Dei sis

Memor Mei." Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan, Fig. 34, a sundial made of ivory, featuring the crucified

Christ with Mary and John, 1544, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuernberg; Fig. 39

a,b,c,d, a pendant watch of a Bishop, gold and bronze, with inscription "O Herre Gott wasche

meine Suende," and crucifix; Fig. 101a-c, ca. 1620, London, pendant watch in the form of a

star, gilded silver, with scenes of the Annunciation, Visitation, Presentation in the Temple,

collection of the "Worshipful Company of Clockmakers," London; Fig. 104a-d, cruciform

pendant watch, silver, ca. 1640, signed Henry Terold of Bury, with engraved scenes of the

Crucifixion, Nativity and Adoration, British Museum, London; Fig. 124, a table clock with the scene of the crucifixion, ca. 1570, Ulm, Collection Dr. E.

Gschwing, Basel; Fig. 187, a figurated table clock, Munich, ca. 1660, featuring the

Apocalyptic Madonna, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Muenchen. Catherine Cardinal and Francois Mercier, Museum of Horology La Chaux D-Fonds Le Locle

(Zurich, 1993), 113, repeater watch by Cabrier, London, mid 18th century,

gold, steel, enamel, shows the Conversion of Paul.

37. Ethel Abrahams, Frakturmalen und Schoenschreiben, (Newton, Kan.: Mennonite Press, 1980), 26, ink and tempera on paper, 14"x17".

38. Meyer, Deutsche Volkskunst, 27.

39. A Sunday Afternoon: Paintings by Henry Pauls (St. Jacob's, Ont.: Sand Hills Books, 1991), plates 20 and 21.

40. Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen, Russia notebook, ms, June 1991; see also Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen, "The Visual Arts in Mennonite Worship," The Mennonite Quarterly Review 73 (April 1999): 388, fig. 11.

41. John M. Janzen. "Form and Meaning in Central Kansas Mennonite Buildings For Worship," The Mennonite Quarterly Review 73 (April 1999): 352, fig. 7b.

42. Geistreiches Gesangbuch zur oeffentlichen und besonderen Erbauung der Mennonitischen Gemeine in u. vor der Stadt Danzig (Marienwerder: gedruckt bey Johann Jacob Kanter, Koenigl. West-Preuss. Hofbuchdruckerei 1780). The foreword concludes with the reward for the devotional use of this book: "... Friede , und Freude in dem heiligen Geist, und dereinstens Theil haben and dem Erbtheil der Heiligen im Lichte..." (no page)

43. Hymnal: A Worship Book, (Elgin, Ill.: Brethren Press; Newton, Kan.: Faith and Life Press; Scottdale, Pa.: Mennonite Publishing House, 1992), iii.

44. The term "restrained eschatology" was coined by Walter Klaassen and is discussed in Marlin E. Miller, Theology for the Church, Richard A. Kauffman and Gayle Gerber Koontz, editors (Elkhart, Ind.: Institute of Mennonite Studies), 77-78.

45. The Complete Writings of Menno Simons, 203.

46. The Complete Writings of Menno Simons, "The Foundation of Christian Doctrine," 109.

December 2000

vol. 55 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents

December 2000

vol. 55 no. 4

Back to Table of Contents