If this site was useful to you, we'd be happy for a small donation. Be sure to enter "MLA donation" in the Comments box.

Kennedy, John F. (1917-1963): Difference between revisions

Created page with "''Mennonite Weekly Review'' obituary: 1963 Nov 28 p. 1 Birth date: 1917 May 29 text of obituary: 300px|center <center><h3><u>The Wor..." |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

[[Image:Kennedy_john_f_1963.jpg|300px|center]] | [[Image:Kennedy_john_f_1963.jpg|300px|center]] | ||

<h3><u>The World's Week</u></h3> | |||

<font size="+2">'''A Moment In History'''</font> | <font size="+2">'''A Moment In History'''</font> | ||

Revision as of 11:00, 16 June 2020

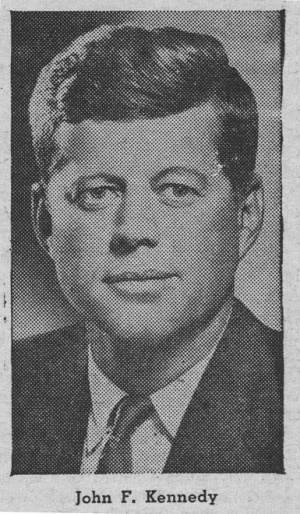

Mennonite Weekly Review obituary: 1963 Nov 28 p. 1

Birth date: 1917 May 29

text of obituary:

The World's Week

A Moment In History

T

HE

doleful drums rolled on Pennsylvania Avenue. Where a President had ridden in triumph, a military caisson bore him slowly along in death. John F. Kennedy was gone, and a world mourned.

The awesome drama was played from beginning to end on one long November week end. On Friday noon the President was in Dallas, vibrantly alive. A few hours later he was back in Washington, dead. Time, space and history itself were foreshortened in a technological age.

“A bad man shot my daddy,” said John F. Kennedy, Jr. three years old the day of his father's funeral. “His world was strangely different, in little ways a child notices, but does not understand,” wrote the UPI. General MacArthur summed up everyone's personal sorrow: “When he died, something died within me.”

A

MERICA'S

self-confidence was shaken. In a country of law and reason and light, the dark and brutal spirit of the jungle possessed the heart of an assassin with a mail-order rifle. A nation accustomed to smugly lecture its Latin neighbors about their violent politics drew itself up short for a searching look at its own soul. What were we coming to? The deep melancholia of an entire people called forth Shakespeare's lines:

For God's sake let us sit upon the ground,

And tell sad stories of the death of kings.

J

OHN

Kennedy was not a king, but no caesar ever had more power to decide the fate of nations — the might of the nuclear thunderbolt. During his brief three years in office, the force of the atom had once again been contained, however precariously, and the world was grateful. His successful efforts for a nuclear test ban treaty raised the hopes of fearful humanity.

The U. S. Chief Executive was more than a national symbol, for he identified himself with the larger cause of mankind, “I am a Berliner,” he declared last June to the throngs in beleaguered West Berlin. A marked contrast to the aged leaders of Europe, the President and First Lady inspired the world with a spirit of youthful optimism.

A

MONG

the ironies of this moment in history was the obvious parallel to President Lincoln, assassinated on Good Friday, 1865, after preserving the Union in the Civil War. Though separated by a century of change, Lincoln and Kennedy faced many of the same basic domestic problems. Kennedy, a strong civil rights advocate, was martyred in the centennial year of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. The London times described the late President as one “who felt that he was challenged to carry forward the implications of Lincoln's work and who, “in this last year, has been seen wrestling with the critical issues of race and national unity.”

With the numbing shock came also a sense of national rededication to making real the ideals of American civilization, and of Christianity itself. John Kennedy's goal on national brotherhood — transcending even racial barriers — was elusive during his lifetime. Now, at his death, it seemed strangely closer to realization.

I

N

the three grief-filled days from her husband's death to his burial, Jacqueline Kennedy was a model of courage. The darkly-veiled young widow bravely led a unique gathering of the world's dignitaries from the White House to St. Matthew's Cathedral for the funeral. Following the requiem mass, quotations were read from the Kennedy inaugural Address (”Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country”) and from Ecclesiastes (”A time to be born and a time to die”).

It was the making of a legend. The statue of the Great Emancipator looked down upon the somber yet majestic funeral procession as it wound past the Lincoln Memorial toward a hero's grave across the Potomac. And the drums rolled. . . .